How to Best Train a Multi-Domain Pilot?: Perspectives from the International Fighter Conference 2019

The International Fighter Conference 2019 provided a venue where a number of key aspects shaping the way ahead for combat airpower could be discussed.

Notable issues, how to best integrate the force as new platforms and technologies are introduced?

How to transition most effectively to multi-domain operations?

How to best connect the force to deliver higher levels of integration to give the force greater combat effect?

And underlying all of this is the key question: how to train pilots to do all of the above?

The transition is a significant one: from the legacy force in which multi-mission fighter training was the key focus, to a focus where warfighting was broadening to require mission command capabilities for pilots operating in a multi-domain combat environment.

Obviously, this is a work in progress and requires new training templates, new technologies, new ways to operate on ranges, new ways to link ranges globally and new ways to combine live with virtual training capabilities.

A key presentation on the comprehensive challenges being addressed was by Major General Kevin Huyck, Director of Operations at the USAF’s Air Combat Command.

The ACC has been focused for a number of years on working ways to leverage the introduction of fifth generation platforms into the force and conducting training exercises for the transition from the legacy fleet to a fifth generation enabled combat fleet.

I have conducted several interviews over the years at ACC and at Nellis AFB with the Air Warfare Center, which reports to the Commander of the ACC.

And those visits and interviews highlighted the significant changes underway in working the transition from the legacy force to a fifth generation enabled one.

The training side is challenging in a number of ways.

First, there is the question of mastering what sensor fusion and machine to machine integration across an F-35 force requires of the pilot.

Second, there is the question of how to leverage the CNI capabilities and its multi-security integration to shape connectivity strategies with other members of the air combat force to shape new task force operational concepts?

Third, there is the question of how to leverage offboarding of weapons from other platforms, or how to operate as an integrated distributed force, as in the case of F-35/Aegis integration?

And notably, how does one train for a combat force which can operate over much greater distances to shape tailored combat effects?

When ranges the size of Nellis, or Fallon can no longer train the force because the combat effects to be delivered are over much wider ranges of activity, how best to train?

Major General Huyck discussed how the training approach was changing to deal with such challenges.

He argued that the training approach at ACC was focused on more rapid assimilation of combat skills and enhanced operational readiness to be delivered by the training and exercise process.

The title of his brief: “Air Combat Command Vision: Advanced Training and Operational Readiness for Contested Environments.’

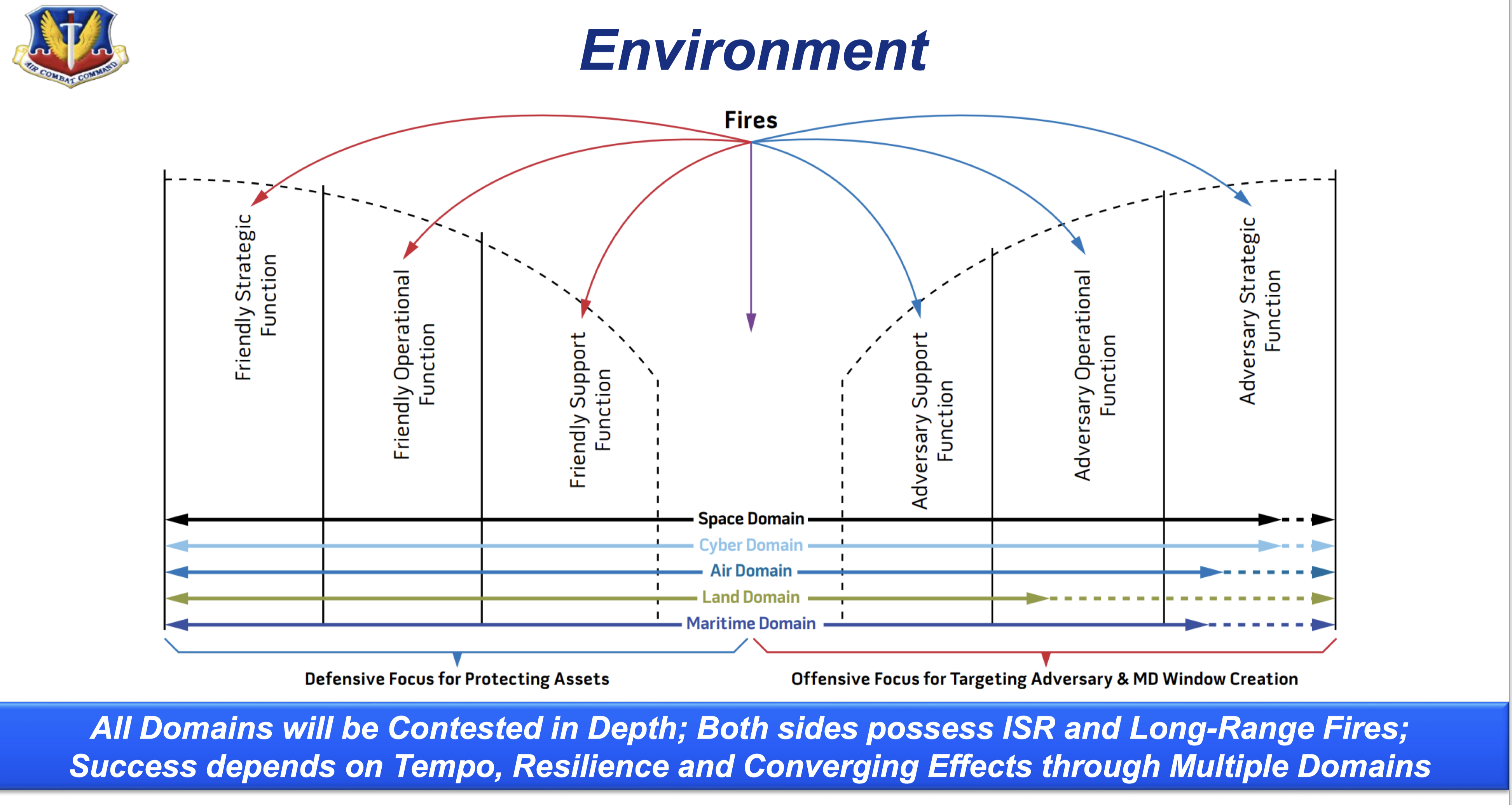

The complexity of the demand side and the need for a C2 structure which enabled mission command by the combat pilot was highlighted in his slide on the evolving combat environment:

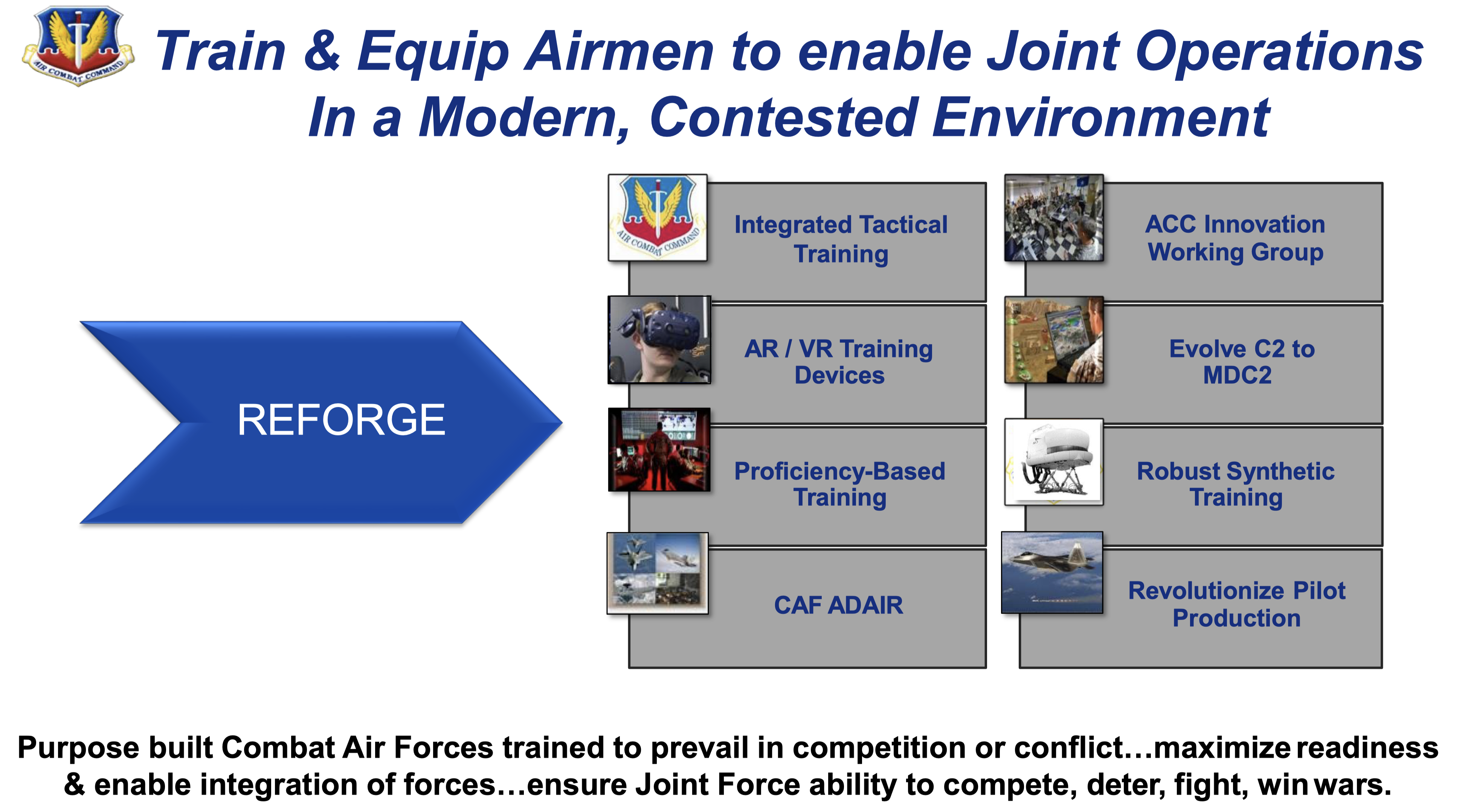

His emphasis was upon meeting the challenge of training and equipping airmen to enable joint operations in a modern, contested environment.

To do so is requiring a major shift in the USAF to the readiness mission, which is how the training focus needs to be considered.

It is not about training to fly the aircraft, or to operate in classic wingman formations, but looking to become able to do reconfigurable task force integration to have the maximum combat effect in a contested environment.

To do so requires looking at shaping new approaches in a number of areas, and to do so interactively over time.

It is not about “finalizing” an approach; it is about building the right templates and allowing those templates to evolve based on combat experience.

He conceptualized the key elements of the new approach in the following slide from his presentation:

He characterized the advanced training environment as requiring pilots to operate in complex scenarios with dense kinetic and non-kinetic defenses requiring integrated, converging effects from multiple multi-domain force elements.

And such training required live, virtual, constructive fourth and fifth generation red air and surface forces engaged in the training environment.

Translated into English this means that the air combat force needs to be able to draw on the capabilities of the maritime, land, space, cyber, and non-fighter air combat elements to prevail in a contested environment and to deliver the combat effects required.

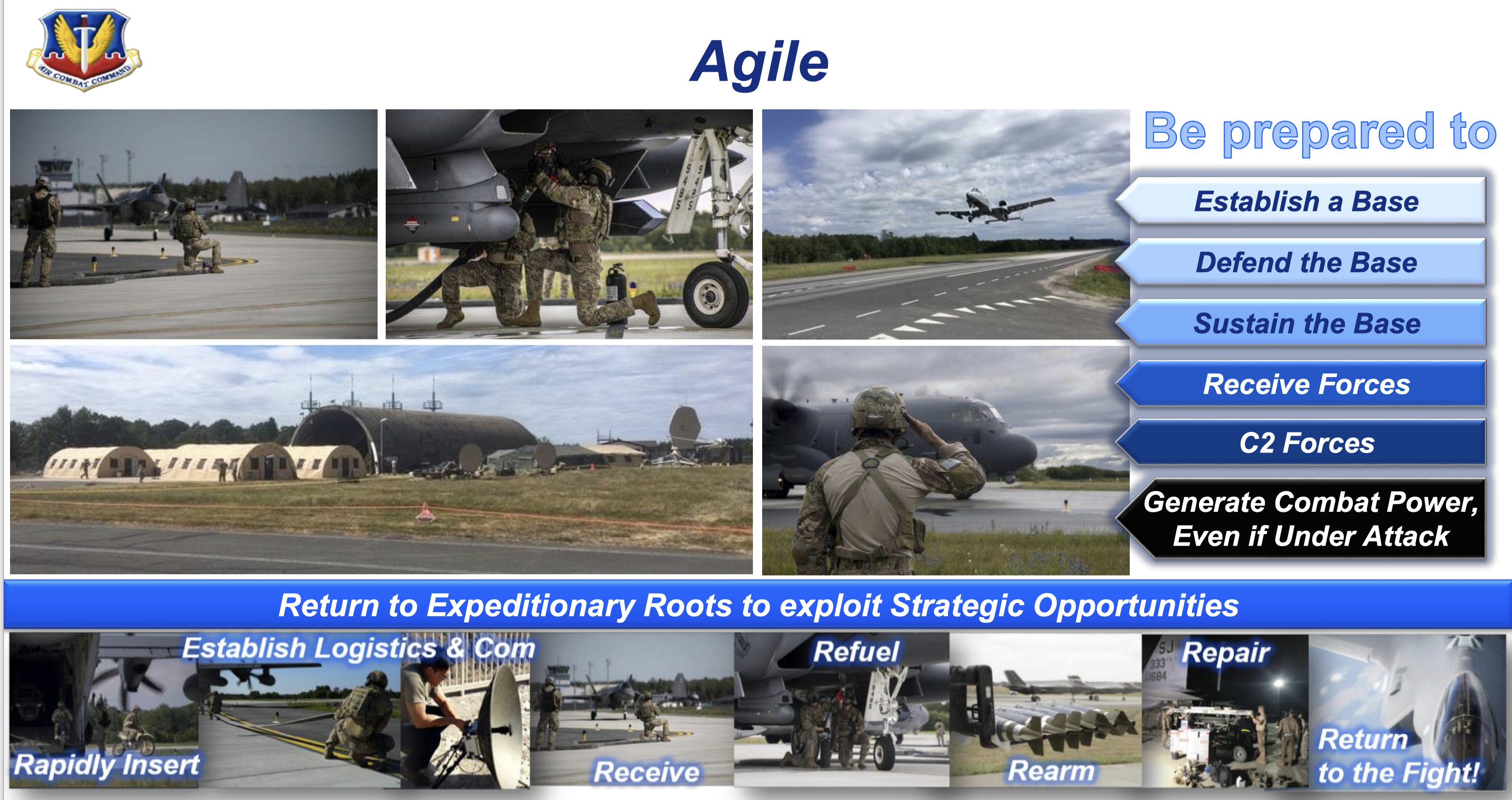

And even more challenging, the pilots need to work in combat teams able to do expeditionary operations.

In the United States, the masters of expeditionary air operations are the USMC, and not surprisingly as the USAF is now re-learning these skill sets one can find them visiting MAWTS-1 in Yuma MCAS.

A major shift from the land wars to operating in a contested environment where being able to master crisis management skills is crucial is the basing component.

In a 2018 comment, USAF Commander, Lt. General Kenneth Wilsbach, highlighted the nature of the challenge requiring the shift to mobile basing as follows:

“From a USAF standpoint, we are organized for efficiency, and in the high intensity conflict that we might find ourselves in, in the Pacific, that efficiency might be actually our Achilles heel, because it requires us to put massive amounts of equipment on a few bases. Those bases, as we most know, are within the weapons engagement zone of potential adversaries.

“So, the United States Air Force, along with the Australian Air Force, has been working on a concept called, Agile Combat Employment, which seeks to disperse the force, and make it difficult for the enemy to know where are you at, when are you going to be there, and how long are you are going to be there.

“We’re at the very preliminary stages of being able to do this but the organization is part of the problem for us, because we are very used to, over the last several decades, of being in very large bases, very large organizations, and we stove pipe the various career fields, and one commander is not in charge of the force that you need to disperse. We’re taking a look at this, of how we might reorganize, to be able to employ this concept in the Pacific, and other places.”

The new context was highlighted in the following slide by Major General Huyck.

The challenge quite frankly is not just technology or new training tools and systems, but space as well.

If you plan to operate in a larger combat space and to draw on the relevant ground, maritime, and non-fighter forces, how do you master such an approach?

So where are you doing this?

The challenge is that live training not just computer aided reality three-D glasses in the simulator training is required.

And indeed, if the simulators are going to be accurate you better have the right real-world data fed into them as well.

And that gets at the big challenge – what training ranges do you now need?

Also, they need to be located where our little Russian and Chinese friends do not have proximate access.

This means that that the ranges in Australia, Canada and the United States become central to advanced training for what I have labelled the integrated distributed force.

And this in turn poses the question of how will Team Tempest or FCAS for that matter train the force they envisage to deliver the right development processes for the right outcomes?

For training and development are not separate worlds any more.

In an interview I did with Air Vice Marshal (Retired) John Blackburn, the opening aperture on the development and training dynamic was highlighted.

The discussion underscored how significant the changes to the training dynamic needs to be to deliver the combat capability of what the Aussies call fifth generation warfare and I refer to as integrated distributed combat force.

Defence is procuring a Live/Virtual/Constructive (LVC) training capability.

But the approach is reported to be narrowly focused on training. We need to expand the aperture and include development and demonstration within the LVC world.

We could use LVC to have the engineers and operators who are building the next generation of systems in a series of laboratories, participate in real-world exercises.

Let’s bring the developmental systems along, and plug it into the real-world exercise, but without interfering with it.

With engagement by developers in a distributed laboratory model through LVC, we could be exploring and testing ideas for a project, during development. We would not have to wait until a capability has reached an ‘initial’ or ‘full operating’ capability level; we could learn a lot along the development by such an approach that involves the operators in the field.

The target event would be a major classified exercise. We could be testing integration in the real-world exercise and concurrently in the labs that are developing the next generation of “integrated” systems.

That, to my mind, is an integrated way of using LVC to help demonstrate, and develop the integrated force. We could accelerate development coming into the operational force and eliminating the classic requirements setting approach.

We need to set aside some aspects of the traditional acquisition approach in favor of an integrated development approach which would accelerate the realisation of integrated capabilities in the operational force.

The scope of the change and the demand side on the training ranges was also highlighted in an interview I did with Air Marshal (Retired) Geoff Brown earlier this year with regard to the kind of training needed for a fifth generation enabled force, or for the projected FCAS force or the Team Tempest enabled force for that matter.

“Today’s Western military is an information-dependent force, one that is wholly reliant on information communication technology (ICT) for current and future military operations.

“The adaptation and integration of ICTs into weapons platforms, military systems, and in concepts of operation has put the battle for information control at the heart of what we do!

“Now while the use of ICT exponentially increases the Western military’s lethality,

“The dependence on these technologies, in many ways, is also a vulnerability. Competitors and adversaries— most notably Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea—recognize this reality.

“Each state plans to employ a range of cyber capabilities to undermine the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of Western allied information in competition and combat.”

Because of this situation several key training questions need to addressed and answered.

The three key questions for Brown are as follows:

How to train in Battlespace saturated by adversary cyber and Information attacks?

How to exploit the advantages of cyber in multi-domain operations

Do we have the tools and key infrastructure to train in an appropriate manner?

“I believe it’s safe to say it is impossible to deny an adversary entirely of the ability to shape aspects of the information environment, whether it’s through spoofing or sabotaging ICT-based warfighting systems. As a result, our goal should be to sustain military operations in spite of a denied, disrupted, or subverted information environment.”

He underscored the challenge this way:

“The requirement is that warfighters need to be able to fight as an integrated whole in and through an increasingly contested and complex battlespace saturated by adversary cyber and information operations. But how to do this so that we are shaping our con-ops but not sharing them with adversary in advance of operations?”

“The battle for information control needs to drive our training needs much more than it does at the moment. We need to provide warfighters with the right kind of combat learning….”

“One of the foundational assumptions I’ve always had is that high quality live training is an essential to producing high quality war fighters but I believe that’s changed

“Even if you don’t take cyber into account, and look at an aircraft like an F-35 with an the AESA radar and fusion capabilities, the reality of how we will fight has changed dramatically.

“In the world of mechanically scanned array radars. a 2v 4 was a challenging exercise — now as we have moved more towards AESA’s where it is not Track while you Scan but its search while track , it’s very hard to challenge these aircraft in the live environment.

“And to be blunt about it, the F-35 and, certainly the F-35 as an integrated force, will only be fully unleashed within classified simulations.

“This means that we will achieve the best training outcomes for aircraft like the F-35 only if we have a more comprehensive virtual environment.”

If we do not do this we will fly fifth generation aircraft shackled by legacy air combat approaches; and we will not unleash the kill web in terms of its complexity and lethality unless we shape a training approach which allows the F-35 working with other key force elements to deliver a kill web outcome.

The featured photo shows U.S. Air Force, French air force and Royal air force flying in formation during ATLANTIC TRIDENT 17 near Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Va., April 26, 2017.

The exercise simulated a highly-contested, degraded and operationally-limited environment where U.S. pilots, allied pilots and ground crews tested their readiness, enhanced interoperability through combined operations, to develop new tactics, techniques and procedures.

(U.S. Air Force photo/Staff Sgt. Natasha Stannard)

Also, see the following:

In the Footsteps of Admiral Nimitz: VADM Miller and His Team Focused on 21st Century “Training”