China and the Australian Submarine Decision, 2021

China has reason to fear the eventual presence of Australian nuclear attack submarines.

According to the Pentagon, China’s deep-water anti-submarine warfare technology is poor. And its nuclear submarines are noisy. America and the UK have over 70 years’ experience with nuclear submarines, whereas China has a long way to go.

Of course, China is likely to make significant strides over the coming decades in quieting its submarines. But in the meantime, it is vulnerable. Its latest ballistic missile firing submarine (SSBN) makes about as much noise as a 1980s Soviet era Delta III SSBN, which were known as “boomers.”

This is important because China’s SSBNs are supposed to be its survivable second-strike nuclear war fighting capability. And it helps to explain Beijing’s anger over the collusion of Australia, the US and the UK in providing us with the world’s best nuclear submarines.

For Australia, our strategic geography has always made huge demands on the technical limits of conventional diesel electric submarines, particularly range and endurance. From our main submarine base in Cockburn Sound near Fremantle to the South China Sea is about 4000 km. That means that we have only a few days on station before having to return to home base. A nuclear attack submarine would be able to travel twice to three times as fast and spend unlimited time on station, depending on food supplies and human endurance.

With the unlimited range of nuclear attack submarines, it no longer matters that our Cockburn Sound submarine base is so far away from potential main operating areas to our north.

The fact that we are acquiring eight nuclear attack submarines will put us in the same rarefied class as the UK and France, which have six boats and seven boats respectively.

The decision to acquire such a potent weapon is a good indicator of the rate of deterioration in our strategic circumstances. Only five years ago – in 2016 –the government’s Defence White Paper was declaring that we faced no risk of direct attack for the next 20 years.

That is now a completely outdated basis on which to make defence decisions.

China has shown no inclination to modify its increasingly aggressive posture towards us.

The decision by the Morrison government to embark upon a three eyes technology alignment with the U.S. and the UK is a realistic reflection of our deteriorating strategic outlook. We have now committed to a regional strategic order underpinned by U.S. power, and we will have access not only to submarine technology but also to a wider range of trilateral collaboration on joint capabilities in such leading-edge technologies as cyber, artificial intelligence, quantum, and undersea remote capabilities.

In practical terms, Australia will make a choice between submarines derived from the U.K.’s Astute class or the U.S. Virginia class. In their baseline form, they are of comparable size: the Astutes’ submerged displacement is between 7400 and 7800 tonnes and the Virginias’ 7900 tonnes. Both are much larger than the Collins class at 3400 tonnes.

The latest version of the Virginias (block V) is larger than the earlier boats (blocks I to IV) at10,200 tonnes. This allows them to carry an additional 28 Tomahawks with a range of about 2,000 kms.

This could make them attractive to Australia, with our increased focus on long-range missiles for strike and deterrence.

The U.S. is planning a production run of at least 34 of the Virginia class and possibly up to about 50 or even more. Current costs of production are $US 3.45 billion per boat.

In contrast the UK expect to build only seven of the Astutes.

The U.S. is more relevant than the UK to Australia’s strategic future and its longer production run would bring greater prospects of through-life improvements and support.

Australia was already planning to incorporate the Virginia’s combat control system in the French Attack.

While some design modifications are to be expected, any tendency towards extensive change needs to be resisted. This would most likely increase costs and lengthen the schedule, potentially significantly, and increase associated risks. We can ill-afford any further slippage.

There will be a need for a high-level of focus on nuclear safety, and the clear communication of this to the Australian public. We will need a specialist and sustainable workforce in the RAN, Defence, and industry. We should establish an Australian Centre for Nuclear Engineering, prospectively in Adelaide to allow ease of communication with the submarine builder.

Such a highly trained workforce would help mitigate any loss of sovereignty that would come from an excess level of reliance on the U.S. or the UK for nuclear expertise. Australia’s negotiations with the US need to guard against the possibility of the return of American policies that reduce its commitment to allies.

All the same, we must also recognise that our shared concerns over China’s assertive behaviour will bind us closer.

An important benefit will be to encourage greater maturity in Australia’s understanding of nuclear issues. A country which takes so long even to decide where to store low-level nuclear waste is still an adolescent –egged on by political opportunism.

The government deserves congratulations on having recognised that the demands of our worsening strategic circumstances require the nuclear nettle to be grasped – despite the public’s engrained aversion to the N-word.

The government has been quiet so far on the questions of costs, but the SSN program will most likely cost more.

This too deserves acknowledgement: the benchmark for future defence spending will be set by tomorrow’s more demanding strategic environment, not the easy decades of the previous 50 years.

Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith are both professors of strategic studies at the ANU. Previously, they were both deputy secretaries of Defence.

This article first appeared in The Australian on September 20, 2021 and is republished with permission of the authors.

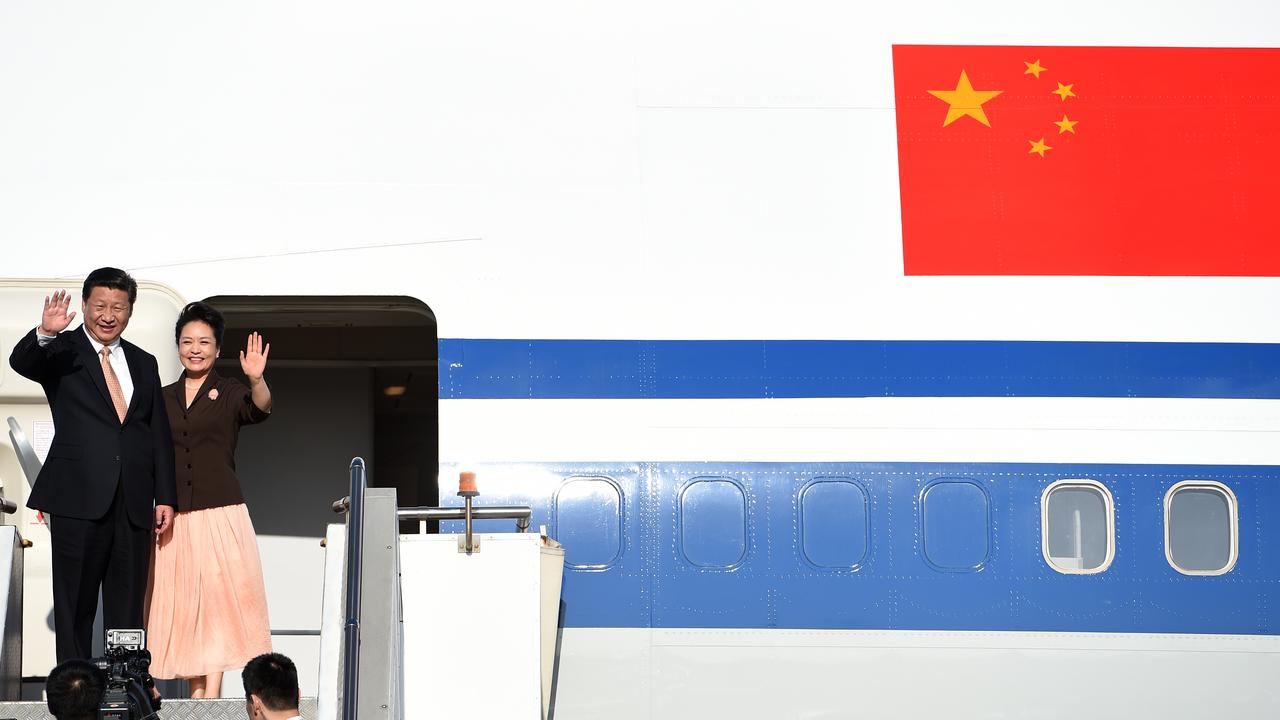

The featured photo: China’s President Xi Jinping and his wife Madame Peng Liyuan during their 2014 visit to Australia. In 2014, President Xi visited Sydney following the G20 Leaders Summit in Brisbane and the signing of a landmark trade deal between Australia and China in Canberra. Much has changed since then, almost completely driven by Xi’s policies and behavior. Picture Credit: Dan Himbrechts