Modern Leadership and the “All Corps Officer”

As more and more Australian Army Field Ranked Officers are being employed in-theatre as out-of-category command staff within Joint and Integrated task forces, it must be asked… Which corps produces the best “Joint” or “integrated” operations officers?

With the diversity in operational scenarios (e.g. peace-keeping, stability, support, offensive, defensive, mentoring, security, etc), is there any corps training and general posting cycle experience that fully covers off on all aspects of all operations?

Which corps do which aspects best?

This article takes a look at what Joint and Integrated task force command staff skill sets and experience levels are needed for these demanding roles, a generalisation based on my experience of different corps officer strengths and weaknesses, some perhaps flawed current training concepts that try to address this skills coverage and a suggested solution to help create the ideal “All Corps Officer” destined for command.

Joint and Integrated Task Force Command Staff

The Joint or integrated command staff officer can find themselves in many roles, including the following J-staff positions and sub-sets thereof:

- J0 – Executive officer

- J1 – Personnel officer

- J2 – Intelligence officer

- J3 – Operations officer

- J4 – Logistics officer

- J5 – Plans officer

- J6 – Communications and Information Systems Officer

- J7 – Training officer

- J8 – Development officer

Each of these positions play a vital role in the continual operational effectiveness of a Joint Task Force (JTF) and their Force Element Groups (FEG), and are generally staffed by an appropriate Corps officer that matches the functionality of the role (J0, J3, J5 – Arms corps officers; J1, J4 – support corps officers; etc), however these roles are subordinate to those of the appointed Theatre and Operational command positions under the Chief of Joint Operations (CJOPS).

The command and control (C2) structure and states of command for operational authorities varies from theatre to theatre, but in general, they are broken into the following delegations:

- Operational Command – Full authority over in theatre operations with the ability to specify missions and tasks, Direct forces, deploy units, reassign forces, etc;

- Tactical Command – Sub-ordinate to the operational command, can still do most of the above (with the exception of reassigning forces), as long as it is in accordance with the mission given by the higher authority;

- Operational Control – This is a command authority that may be exercised by commanders at any echelon at or below the level of combatant command. The authority is limited to directing forces and deploying units for specified missions; and

- Tactical Control – this is a joint doctrinal subset of authorities that is subordinate to Operational Command. It limits authority to direct control of administrative movements or manoeuvres within the operational area as necessary to accomplish missions.

To be appointed to one of the above C2 roles in theatre, you must meet a minimum set of qualifications, including but not limited to:

- Rank and time in rank;

- Command and staff training;

- Command history (platoon, company and unit level);

- Deployed experience;

- Achieved certain competencies and career milestones;

- Etc.

But the question is, do any of these qualifying factors actually guarantee that the appointed C2 staff shall be competent and effective in their roles?

Are their command styles compatible with the operation itself and do they have enough breadth and depth of experience to employ all facets of their command influence effectively?

What makes an effective joint and integrated operations commander is the right blend of experience with the following command philosophy and principals:

- Unity of command – only one recognised command authority at any time and clear delineation of command authority;

- Clarity – Clear and rigid chain of command;

- Delegation of command – utilise the principal of centralised command with decentralised execution;

- Resource control – significant resources, such as special forces, strategic aircraft, submarines, etc. should not be delegated beyond the control of the operational commander;

- Obligation to subordinates – The Command staff should always consider the interests and well-being of their subordinates and represent them within their chain of command;

There are many other command philosophy principals that should be considered, such as flexibility, risk aversion, information management, etc. however, we are now concentrating on which corps officers tend to fit the requirements best.

The Corps officer

This section will take a generalised look (based on my own experiences) at different corps officers and their relative strengths and weaknesses with respect to the requirements of joint or integrated command:

Infantry:

Strengths – best battlefield strategists, offensive and defensive operations, area denial. Good use of communications and intelligence.

Weaknesses – Worst with logistics support prioritisation and movements, Reliability/availability/maintainability (RAM) of fleet and inventory, rotational and sustainment planning and taskforce morale (if things aren’t difficult enough… they can fix that).

Armoured:

Strengths – Excellent with Movements, offensive operations, RAM and maintenance planning. Good with log support, battlefield strategy and area denial, sustainment planning and taskforce morale (why walk when we can drive).

Weaknesses – Not as good with defensive ops (all about covering ground and breaking the line), tend to neglect other battlespace effect multipliers like air cavalry and strike, comms and intelligence usage.

Artillery:

Strengths – Excellent with use of comms, logistics support, offensive and defensive operations. Ok with area denial, RAM, maintenance planning and morale.

Weaknesses – Not so good with battlefield strategy, battlefield manoeuvrability and use of intelligence.

Battlefield Support Corps (Aviation, Engineers, Signals, Intelligence):

Not as likely to be in command at the pointy end, but have vital input into battlefield strategies, capability utilisation, combat support, area denial tactics, command and control, real-time analysis, etc. A good commander will always utilise these inputs to maximum effect.

Service Corps Officers (RAEME, Ordinance, Transport) :

Even less likely to hold command roles in combat task force, however play a vital role in keeping the taskforce fed, equipped, moving and serviceable. Although it regularly happens, service corps effects should not be overlooked, regardless of the situation.

Even in constant combat and possible over-run scenarios, if you haven’t taken consideration of these combat support functions, you will run out of ammo, fuel and food, have no redundancy in crucial equipment and weapon systems and be unable to manoeuvre, advance or retreat your taskforce if needs be.

All this considered, which corps produces the best Joint or integrated task force command staff? Does any corps truly cover off on all requirements well?

Current strategies for Joint Command Preparation

The ADF’s current take on preparing its officers for joint and integrated command is to attempt to generalise the training of all officers, regardless of their corps or experience, to the same level and standard.

So much so that an Army LTCOL in both Infantry and Ordinance share almost 90% commonality in their promotion pre-requisite training (RMC, Officer Grade 2&3, Command and Staff College).

Although this may seem on the surface as a good tactic to have all officers share a common training background, thus ensuring they will all be equally prepared and proficient in command scenarios, the reality is that just because a person has passed a course, or gained a “proficiency”, does not mean that they shall retain any of what they learned unless they put it into practice.

After these courses are completed, the individual officers return to their posted locations and go right back to the jobs they are assigned.

With the exception of the officers that are returning to platoon, company and unit level command, the majority of officers just place their learnings into the back of their minds and continue to concentrate on their posted roles as staff officers, training planners, project staff and specialist service officers, rarely finding the need to use the info they gathered on course.

The question should be asked… what was the point of sending these officers on these courses in the first place?

I remember the feeling of sheer farcicality as I sat in a Grade 3 TEWT and listened as the Padre’s and nursing officers delivered their plans for a Brigade level assault – talk about a waste of everyone’s time!

There are some “high flying” officers out there that do manage to obtain an ideal career development path that grooms them for these prestige Joint and integrated command roles, but often, combining this trajectory with the right person who has the natural aptitude and leadership qualities required to maximise this effect, seems like more good luck than good management, and maybe one in three of these rotational joint command positions are filled with these highly competent characters due to their scarcity. So what can be done to ensure that the ADF is identifying and producing officers that are up to the mark for Joint and Integrated Command?

The “All Corps Officer” Concept

There is an argument for a new brand of officer, that is groomed specifically for these highly complex command roles through an extensive selection, training and career development program that ensures, not only that you get the most suitable candidates, but they receive the breadth and depth of training and experience required to develop all the knowledge and skills to be effective Joint and Integrated task force commanders.

The following is a suggested methodology for this approach:

- Selection: It must be established that this is a prestigious and highly competitive program to ensure that it attracts the cream of the crop. Officer Cadets at RMC should be assessed for their suitability for this career path and it should attract the best and brightest. Due to the rigours and breadth of the training they will undergo, candidates should be not only be fit, strong and mentally tough enough to be considered suitable for SOCOMD, they should also be academically inclined enough to become a tech qualified service corps officer.

- Training: A staggered continuation training program should be established, where the selected officers undergo a variety of courses across the Defence capability during their initial development posting cycle. It should include attendance at the various combat and logistics corps beginning, intermediate and advanced courses, regular officer grade and staff courses, technical staff officer courses, NATO observer and O/S exchange courses as well as some specifically developed courses around Joint and Integrated Command. The training should be spread out in a logical sequence that aligns with their rotational postings to ensure the learning is reinforced through practical application.

- Posting Cycle: The selected officers should undergo a rotational posting cycle that includes various key operational command and support roles.

These roles should include:

-

- Infantry platoon command

- Armoured troop command

- Artillery battery command

- Engineer corps officer

- Signals corps information systems officer

- Aviation corps GSO

- Intelligence officer

- CSSB sub-unit command

- SOCOMD exposure

- NATO observer or command role

- Possible US/UK exchange posting

Due to the number of different vocational exposures being attempted, it would be pertinent to limit the positional posting duration to between 6 and 12 months each.

This would be hard on the individuals and any dependents they have, but the trade-off would be for the officers to graduate this program as an O4 rank, at least a year or two earlier than their peers. It should also include where possible, a deployment as a junior staff officer or within a junior command role.

Their first posting as a fully qualified “All Corps Officer” should be as a staff officer within brigade command, being directly involved in brigade level operations and planning and rubbing shoulders with experienced and senior officers from all walks of life.

During their initial and subsequent postings, it should be a priority to get them deployed to get maximum exposure to real Joint and Integrated operations. They should rotate through the Joint officer roles as deployment cycle extension and full time J-staff (at least J0, J1, J2, J3, J4, J5), getting a full appreciation of their roles and responsibilities prior to taking command.

Once these individuals have completed their extensive OJT, they should be better prepared for any Joint or Integrated command roles than any other officers that have preceded them.

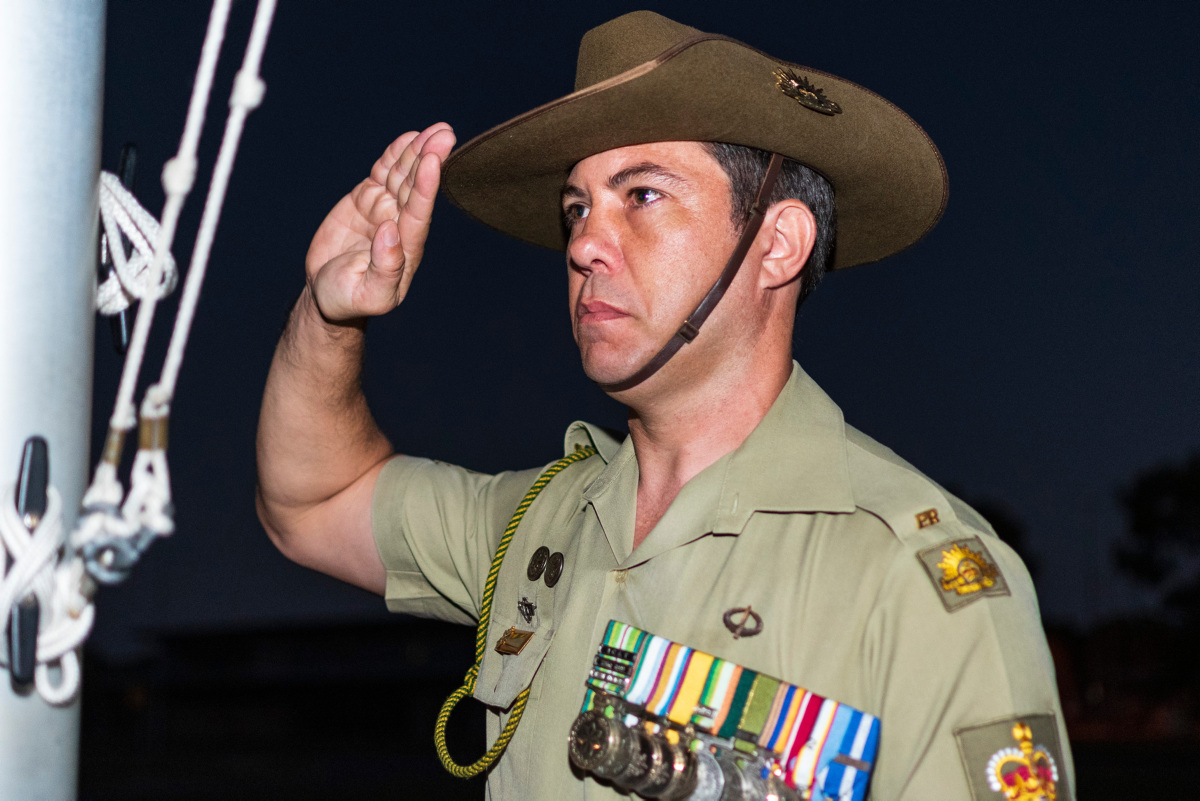

Featured Photo: Australian Army soldiers Warrant Officer Class 2 Neil Ruskin from the Joint Operations Support Staff North Queensland salutes the flag during the ANZAC Day commemoration held at Lavarack Barracks, Townsville.

Australian Department of Defence: April 25, 2020.