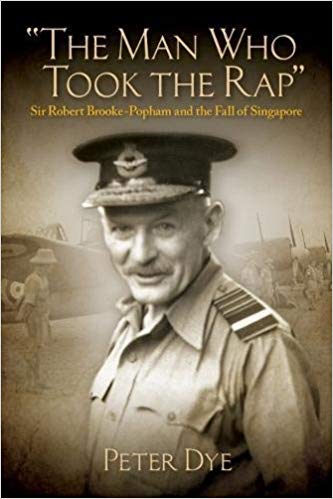

“The Man Who Took the Rap”

The subtitle of the book is: “Sir Robert Brooke-Popham and the Fall of Singapore.”

This is a well researched and well written book on the life of the man who would be best known for a nation’s failure, the loss of Singapore in the face of a Japanese tidal wave, rather than in terms of his distinguished career in the RAF and in the British Armed Forces.

The author himself was a long serving officer in the Royal Air Force and was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his work in support of the Jaguar Force during the First Gulf War, retiring as an Air Vice-Marshal. His own background in the RAF and in the joint forces clearly inform the book throughout and provides more than a biography.

It provides a way to look at the evolution of the RAF through its formative years up to and through the initial phases of World War II.

The book is a first rate biography, but throughout the book there are lessons to be learned for today, notably with regard to the Pacific.

The Fall of Singapore is really about absence of the capability to execute an effective war plan against a determined adversary.

And as we face challenges in today’s Pacific, we need to be aware of the gap between aspirations and reality as well as never underestimating the capabilities of an adversary who does not think like us, but by following their own logic can achieve combat and diplomatic success.

The richness of the book can be suggested by a series of vignettes which I will highlight from the narrative of the book.

The first involves Brooke-Popham’s involvement in the formation of the RAF and its role in the First World War.

Here he was on the ground floor for the stand up of the RAF and its preparation for what would be known at the Great War.

In that war, he played a central role working the logistics of the RAF on the continent and working the relationship between the force and industry in building out the ongoing modernization and replacement of aircraft throughout the war.

In so doing, he established a staff with whom he could work effectively, and to reach back into communities driving modernization, build out and support of the combat force. In other words, he was at the vortex of the infrastructure which drove the availability of a combat force.

By the time he left France in February 1919, he had spent 53 months continuously on the Western Front.

For more than four years he had provided the RFC (and later the RAF) with an incisive and intuitive grasp of its needs.

His instinctive, intelligent, and seemingly instantaneous reactions in dealing with multitudinous problems and difficulties provided the essential foundation for air operations on the Western Front , creating the vital bridge between the nation’s economy and airpower.”1

A second vignette revolves around his time in Iraq from 1928-1930 in charge of the Iraq command.

Just reading through this chapter (Chapter 9) is a good reminder of those who do not study history are condemned to repeat it.

Here we learn that the Army lectured the Air Force on the impotence of airpower compared to the ability to control the ground.

We learn that the British were banking on the Iraqis taking charge of their own security and spent significant time training Iraqis to do that mission.

Unfortunately, reading through this chapter is as much about history repeated in our period as it is any recounting of Britain in Iraq.

It would be amusing to read the following paragraph if perhaps it was not so much about the distant 1920s.2

“The political and security situation in Iraq during the late 1920s was complex and uncertain.

“The policing of Iraq’s borders was a difficult task at the best of times, even with the RAF’s help.

“In the absence of natural features or habitation, it was possible to cross from on country to another without hindrance of the knowledge of the authorities.”

A third vignette involves his time reshaping the RAF prior to the establishment of Fighter Command. He was a key player in the reshaping of the RAF to work the air defense of Britain/

As head of Air Defence Great Britain (ADGB), he worked with his team on preparing the ground for what would become Fighter Command.

“He played a major role in the development of Britain’s air defenses for more than a decade…. As chairman of the ADGB Sub-Committee, he laid the foundation for a comprehensive and robust air defense network that would be validated under the most testing of conditions…..He was the first senior officer to appreciate the value of scientist when others were still refusing to admit them to their headquarters.”3

After his time with ADGB, he becomes Inspector General of the British Forces and in this capacity traveled throughout the Middle East and worked on the military side of the European situation. He was then sent to become Governor of Kenya in 1937 through 1939.

You might be asking yourself, OK why does he end up in the Far East after the knowledge and experience which he had gained with regard to the RAF, the joint force, the Middle East, Africa and Europe?

Well the simple answer is that you don’t appoint yourself to senior positions.

This takes folks wiser than we are — namely, politicians.

He was indeed very surprised to be appointed Commander in Chief Far East.

Here he was dealt a hand of trying to deter the Japanese with limited resources, working alliances among the powers in the region to curtail the Japanese, and to try to shape an air-maritime-ground capability which could defend Singapore.

The key was to have enough first line aircraft integrated with a maritime force (Force Z) to dissuade the Japanese from attacking Britain and its allied forces.

Unfortunately, the Germans had captured the secret documents generated by the British government describing in detail its strategy and force disposition.

It is a bit difficult to dance a Kabuki dance with your adversary when he already knows your moves and holds the script guiding your actions.

The final third of the book provides a detailed look at the Singapore and Pacific disaster and is worth the read all by itself.

And throughout the narrative are informed judgments about what happened, why and perhaps actions which might have been taken to deal with the coming Japanese attack.

Here is one example of the kind of insights one can find in this part of the book.4

“The Japanese attack on Malaya and at Pearl Harbor was not the first (not likely the last time) the American and British governments failed to anticipate the actions of a foreign power.

“There are many similarities with the Ar gentian occupation of the Falklands in 1982 when ministers and the intelligence services, aware of increasing Argentinian frustration and nationalist fervor, simply did not believe that an invasion would take place.

The cognitive behavior that contributed to this strategic blindness included:

“Transferred Judgment”: the erroneous belief that others, even non-democratic states, will be deterred by the same factors that would make you hesitate.

“Mirror-imaging”: The assumption that others are likely to act as you would act under the same circumstances.

“Deception”: The aggressor’s actions to hide true intentions.

“Perseveration”: The psychological phenomenon whereby initial errors are very difficult to correct alter. Such anchoring errors can provide robust, even in the face of conflicting and contradictory information.”

In short, this is an important work.

Not just for what it tells us about an historical figure, but what it reminds us of what history can tell us if we pay attention to her and can actually learn.

My father used to tell me that it was not wrong to make mistakes; just making the same one repeatedly.

And by the way, he fought in the Pacific during World War II.