The C.R. Boxer Affair: Heroes, Traitors, and the Manchester Guardian

Heroes come cheap these days.

The word is used so promiscuously for well-paid sports stars and short-lived celebrities that when a real hero appears he or she makes people uncomfortable.

The recent presidential election showed a real hero entering the race – Senator John McCain – a figure who is not very popular among his fellow senators, but a truly exceptional man who survived long years in solitary confinement and torture as a prisoner of war in Vietnam to emerge as the leading advocate of reconciliation with his former torturers.

Charles R. Boxer was such a man, both a victim and an admirer of the Japanese, and who, like Senator McCain, makes some of his former colleagues resent his magnanimity.

Therein lies the problem with the current C.R. Boxer affair, a mixture of old resentments, gossip and jealousies from a lost colonial world now working to violate the reputation of a truly complex and remarkable individual.

“Charles Boxer was a good soldier and a brilliant historian. But… was he also a traitor whose information prolonged the Second World War?”

So begins the headline of an article in the English newspaper The Guardian, written by Hywel Williams and published on February 24, 2001. In his article, Williams claims that Boxer “may” have been a “traitor” who handed over “… his fellow officers to a Japanese-run prison camp in Hong Kong in a way that undermined the entire British intelligence system in South-East Asia”. Boxer, continues Williams, was “a globalist intellectual ahead of his time” whose work “forged the assumptions of post-colonial and anti-Western elites in Brazil, West Africa and Japan, where it is read, translated and celebrated”.

William says that Boxer fell “under the spell of the Japanese cultural style, its combination of aesthetic-intellectual refinement and politics of force”. He was like, he continues, “the generation of Philby-Burgess-Maclean-Blunt, English intellectuals (who) embraced Marxist communism on the Soviet model”. Boxer, he says, like “other members of his (social) class, found another country and another cause in the East”. After the war, “collaborators quietly left the scene without much punishment.” Boxer’s case, writes Williams, could be “a spectacular example of wartime temptation”.

These are heavy accusations against one of the twentieth century’s greatest historians, coming from one of Britain’s most respected newspapers. Formerly known as the “Manchester Guardian”, this newspaper has been, since its foundation in 1821, the strongest liberal voice in Britain, independent, non-conformist, an uncompromising defender of unpopular causes. It is the British newspaper that I have read diligently over the years, and I have long admired its texts and reports. Its pioneering Guardian Weekly incorporates selections from Le Monde and The Washington Post.

Charles R. Boxer died last year at the age of 96. This protects the newspaper from the risk of a libel charge.

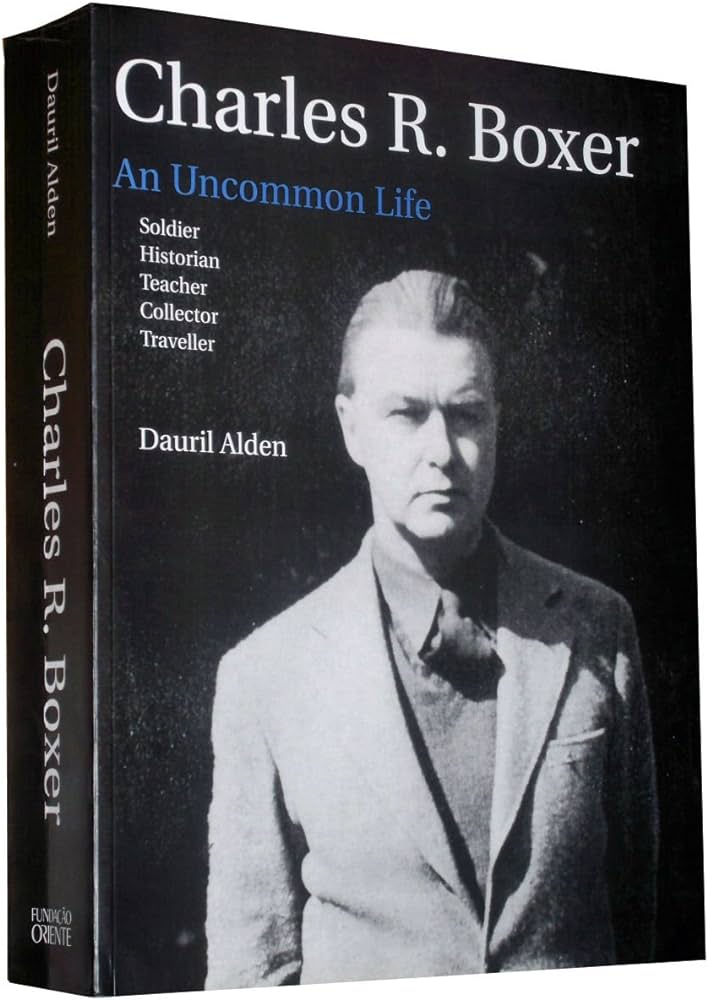

In its March 10 edition, The Guardian published a detailed rebuttal of Williams’ accusations against Boxer written by American historian Dauril Alden. Coincidentally, Alden has just finished a biography of Boxer which will soon be published in Lisbon by the Fundação Oriente. Professor Alden is a meticulous scholar of the old school for whom solid documentation is the core of historical scholarship. His detailed refutation of Williams’ accusations against Boxer can be read on the “Guardian” page, where the newspaper originally published and still maintains a reference to William’s attack, albeit now under a modified and less insidious headline.

Curiously, however, William’s article itself has been removed from the site’s archives, making it inaccessible. Such camouflage in cyberspace is despicable – if The Guardian is ashamed of what it has published, it should say so. It is difficult to understand the lapse in editorial judgment that led The Guardian to lend its pages to such an obscene attack, full of innuendo, inaccuracies and undocumented defamations to the honor of the most honorable of men.

And this in no way exempts The Guardian from the moral obligation to apologize to Boxer’s family and its own readers for this grotesque transgression of its high journalistic standards. We must assume that, under English libel law, if any of the individuals attacked in Hywel Williams’ article were still alive, The Guardian would be facing the likelihood of founding several academic chairs on Portuguese imperial history in honor of Boxer’s memory.

For generations of historians from Portuguese-speaking countries, C.R. Boxer was a true colossus.

Groundbreaking, substantial and highly original, his books, monographs and articles flow effortlessly.

Boxer’s works cover the history of the earliest European incursions into Japan and China during the sixteenth century, and splendidly narrate the opulence and decline of Goa, the seat of Portugal’s empire in Asia. In more than 350 publications, all of the highest erudition, Boxer wrote about the naval wars in the Persian Gulf in the sixteenth century, the tribulations of the maritime trade routes between Europe and Asia, the glittering panorama of Brazil in the period of the gold discoveries and frontier expansions in the eighteenth century, magnificent syntheses of the colonial history of Portugal and Holland, as well as many pioneering comparative studies of municipal institutions in Asia, Africa and South America, race and social relations.

Notably in the 1960s, at the height of the Portuguese colonial wars in Africa, he challenged the “Luso-tropicalist” propaganda of Salazar’s dictatorship by tracing its roots back to Gilberto Freyre’s assertion that the colonial Portuguese held no racial prejudices, and was systematically defamed by the regime and its defenders.

In my opinion, Boxer’s magnificent account of the career of Salvador Correia de Sá Benevides (1602-1686) is one of his best books.

This “remarkable old stickler”, as Sir Robert Southwell called Salvador de Sá in a letter to Lord Arlington in 1667, played a decisive role in the titanic seventeenth-century struggle between the Iberian powers and the Netherlands for hegemony in the South Atlantic.

The inscription on his now lost tomb in the convent of the Discalced Carmelites in Lisbon praises Salvador de Sá as “Restorer of the Faith of CHRIST in the Kingdom of Angola, Congo, Benguela, São Tomé and conqueror of the Dutch”. As Boxer demonstrated, to this praise should be added savior of Portuguese Brazil.

Remarkably, Boxer only entered academic life formally in middle age. Without a university degree, but on the strength of his remarkable erudition, he was nominated in 1947 for the prestigious chair at King’s College in London, named in honor of the great Portuguese poet Luís de Camões, author of Os Lusíadas. He accepted the job at King’s College, he said, because there was no real competition: “it’s like the platypus. I’m the only one of the species”.

Boxer’s skills were so intimidating that, when I wrote him a letter from Lisbon in 1963 to ask how one should prepare for the field I intended to enter, he almost made me give up. The basic qualifications, he said, for anyone studying the Portuguese empire were a combination of languages comprising Dutch, French and Italian on the European side, plus Portuguese and Spanish, as well as, when studying Asia, a minimum of Japanese and Chinese and the paleographic skills to be able to understand archival documents in as many of these languages as possible from 1500 onwards. A strong grounding in the classics was also recommended, as was a vast knowledge of religious literature and the theological controversies within the Catholic Church and between Catholics and Protestants after the Restoration.

He didn’t say this to boast: he didn’t tolerate pretension. He merely recited some of the skills that he himself possessed and used so effectively in his work. Despite his eminence, he was extraordinarily generous with his time and advice to the less gifted.

Although Boxer was known to have been a soldier into his forties, there was another Boxer about whom we – or at least I – knew little.

There was Boxer the spy and Boxer the lover. Monsignor Manuel Teixeira, a nonagenarian Portuguese priest and Macau’s leading historian, once asked Boxer about his religion. It was well known that, as a prisoner of war of the Japanese for almost four years in Hong Kong and later in Canton (Guangzhou to the Chinese), he had rejected the Bible in favor of the complete works of Shakespeare, a decision that annoyed the fearsome old priest, with whom Boxer had a long and friendly rivalry. Boxer, whose taste for bawdy jokes and campfire chatter was notorious, replied: I’m Episcopalian from the waist up and Mormon from the waist down.

In the case of the Mormons, he was obviously thinking of polygamy, not the Salt Lake City Tabernacle Choir. Boxer’s affair in Hong Kong with American journalist Emily Hahn was one of the most public romances of the twentieth century. For seventy years, Hahn, known to friends and relatives as “Mickey.” was one of the most prolific contributors to The New Yorker magazine. Like Boxer, her literary output was impressive – 52 books and hundreds of articles, short stories and poems. Her wartime affair in Hong Kong was fully revealed by Hahn herself in her bestseller “China to Me: A Partial Autobiography”. She died before Charles Boxer, in 1997, at the age of 92.

For many who followed her adventures over the years, Emily Hahn was the star and Charles Boxer the handsome military man. Her obituaries in the United States barely mentioned him or his achievements as a scholar. For Emily Hahn’s audience, Charles Boxer was forever the British major from Hong Kong who became her lover, the father of her children and her husband for more than fifty years. Boxer and Hahn settled in his country house in Dorset in the late 1940s, but Hahn didn’t fit the role of castellan of a cold English manor in the uncomfortable conditions of the post-war British countryside. Her over-accurate comments on British manners and foibles, published in “England to me” in 1949, were not much appreciated by her adopted compatriots. After 1950, his marriage to Boxer became a transatlantic barter. Hahn avoided Britain’s taxes with quick stays, while Boxer, after a post at Yale University, when in the US stayed at the Yale Club on Vanderbilt Avenue, behind Grand Central Station in New York.

Emily Hahn was born into a German Jewish family in Saint Louis, Missouri, in 1905. In 1926, she received the first mining engineering degree given to a woman by the University of Wisconsin. In the early 1920s, she drove across America in a Model T Ford dressed like a boy and settled temporarily in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her letters to friends in Chicago, where her family had moved, provided the material sent to but initially rejected by the New Yorker. She worked as a screenwriter in the early days of Hollywood, studied geology at Columbia University in New York and had her first text published by the New Yorker in 1929. When a novel in California ended badly in 1930, she went to Africa, settling among the pygmies in the Belgian Congo and becoming fond of the gibbons. From then on, at least one of these slender, long-armed arboreal monkeys accompanied her everywhere, perched on her shoulder.

In 1935 she stopped for a few days in Shanghai. “It was clear to me on the first day in China that I was going to stay there forever,” she later wrote. In China, she met the Soong sisters. The eldest was married to Doctor W.H. Kung, a wealthy Shanghai banker and prime minister of China in the late 30s. Another Soong sister was married to Sun Yat-sem, founder of the Chinese republic, still revered by both the Nationalists and the Communists. The third sister married Chaing Kai-shek, the Nationalist leader.

Hahn wrote the story of these remarkable women in his book “The Soong Sisters”, published in 1941. In Shanghai, she had a long affair with one of China’s leading poets and intellectuals, Zau Sinmay, and became addicted to opium. She was friends with luminaries of the local scene, such as Sir Victor Sassoon and C.V. Starr, editor of the American Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury and sponsor of Sinmay’s failed attempt to create a bilingual literary newspaper. She met the young communist rebel leaders Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. All the while she wrote reports as the New Yorker’s China correspondent, recording in vividly autobiographical detail life in China against a backdrop of civil war, revolution and Japanese invasion.

When Emily Hahn became Charles Boxer’s lover in 1940, he was already “an old Asian hand”, as they used to say in British colonial circles. Boxer, who worked for British military intelligence, had married Ursula Tulloch in 1939. Hywel William, in his article in the Guardian, states that Tulloch, known as the “most beautiful woman” in Hong Kong, was also one of the most promiscuous. Her goal, says Williams, “was to sleep with the entire Far East information community.” A wonderful English euphemism for the word “sleep” in this context. Sleep was presumably the last thing, Williams suggests, that Ursula Tulloch, Boxer or anyone else was thinking about when they went to bed in Hong Kong. Boxer and Ursula Tulloch were the main swingers in the colony, says Williams.

Alf Bennett, one of Boxer’s oldest friends, who arrived in Hong Kong in 1939 to join the Far East Intelligence Bureau and, after the headquarters moved to Singapore later the same year, remained in Hong Kong and worked in an office next to Boxer’s, seeing him every day. Alf Bennett was kind enough to share with me his reaction to the article in the Guardian.

According to him, “whatever he wanted to induce with swingers, a word that didn’t exist back then, is complete nonsense.”

Boxer was a drinker and liked to party, but as Alf Bennett says, “Charles went straight back to his books to write a scholarly article”.

Ursula Tulloch also went from Hong Kong to Singapore. It was assumed, wrongly as it turned out, that Singapore would be safer in the event of a Japanese attack and was, in any case, impregnable. When this confidence proved disastrously wrong, Ursula managed to escape when Singapore fell to the Japanese in 1942, arriving in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where she decided to remain working as a cryptographer. In 1947, after divorcing Boxer, she married I.A.R. Peebles, a Sunday Times journalist and well-known sportsman. After Peebles’ death, she remarried. Ursula Tulloch, of course, like Charles Boxer and Emily Hahn, is no longer around to refute Williams’ accusations. She died in 1996, aged 86.

Boxer met Hahn first in Shanghai, startled when he was greeted in the editorial office of Sinmay’s magazine by “a huge monkey… wearing a red hat…” This was Emily Hahn’s companion, the gibbon-wearing “Mr. Mills.” Boxer told her that he was also a writer, “stuff about history, very boring.”

But, as he was led to understand, Emily and Sinmay “were characters in one of the world’s great love stories, so naturally I didn’t want to interrupt.” Hahn found Boxer to be a “mad, funny, brilliant man, who insisted on chatting about Chungking politics, which I knew nothing about, while dueling with the approaching dissolution of the British Empire.”

After Hahn congratulated him on the wedding, he said, “That always happens to people who live in Hong Kong. You either become a hopeless drunk or you get married. I did both.”

When Emily Hahn went to Hong Kong with Sinmay, “the Major”, as she invariably called Boxer, opted for a direct approach. At dinner, he overheard Hahn say that she couldn’t have children. Well, Boxer told him, I don’t believe that, let’s see, and the child can be my heir. Carola’s subsequent birth, in November 1941, took place six weeks before the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese assault on Hong Kong came soon after. After holding out for 16 days, the British surrendered at Christmas that year, the centenary of the British annexation of Hong Kong during the Anglo-Chinese Opium War, which lasted from 1839 to 1842. Boxer, who had refused two Japanese demands for surrender on behalf of the British governor, was severely wounded.

The mission of handing over the formal surrender of Hong Kong to the Japanese then fell to his friend Alf Bennett, who spoke Japanese and had served in Japan. He was very sad to have been given this responsibility. Emily Hahn gave a remarkable description of Alf Bennett in 1940:

Alf was an officer in Her Majesty’s Air Force, always deliberately funny and full of glamor. He had an incredible mustache, turned up on end like his father’s character in Clarence Day’s play. He suffered from high blood pressure and his voice was raspy; he roared and drank, knew good poetry, and liked to present himself as a picturesque figure, which indeed he was. Picturesque and privileged. Everyone knew Alf, and women dreamed of him, although they were always a little wary.

Boxer had no doubts about the outcome of the war, even when he was seriously ill in hospital as Hong Kong fell. “In the end, they can’t win. I don’t see how they can, do you? Against America, England, Holland and China? We just have to survive, that’s all.”

Boxer came from a family with a long military tradition, born in 1904 on the Isle of Wight. He was educated at Wellington College, named after the Duke of Wellington, who defeated Napoleon at Waterloo. He later studied at the Royal Military Academy in Sandhusrt, before being commissioned into the Linconshire Regiment as a lieutenant in 1923. His father, who served in the same regiment, died at the Battle of Ypres in 1915. It was a typically heroic and unnecessary death, as were so many others on the killing fields of the western front of the First World War. He had already been severely wounded while serving General Kitchener in Egypt but, when the world war came, he insisted on returning to active service. At Ypres, he led his men out of the trenches as the machine-gun fire died down. He leaned on a cane while leaning on the shoulder of his orderly.

Following his language and intelligence training, Charles Boxer was assigned to the Japanese army in 1930 for three years as part of an exchange agreement between Japanese and British officers. He was assigned to the 38th Infantry in Nara. “In armies, intelligent people usually go into the cavalry, but in Japan it’s considered to be much more stupid and aristocratic and not at all close to the infantry,” he said in 1989 in an interview we recorded at Columbia University’s Camões Center. Boxer liked Japan: “When you’re young, have money and seek lust like an eagle, you always do.” There he learned Japanese kendo fencing – “today everyone fights, but in 1930 foreigners learned jiujitsu. I was the first to learn kendo.”

As he explained, “I was quite pro-Japanese anyway and the older generation was a bit pro-British … that was a country for men and if you knew Japanese, and I did, you were fine.” Not that women were absent from Boxer’s life in Japan. His concubine governess was from the north, from Kakoadati on the island of Kakkaido. “There was no secret about it. She had been someone else’s concubine before and was very reliable.”

It was in Japan that he expanded his interest in Portuguese imperial history, focusing his attention on the first disastrous experiment of European incursion into the country and its catastrophic end when Tokugawa closed Japan to outside influence in the 1640s. The Japanese literally crucified hundreds of missionaries and Christian converts and for safety’s sake executed the delegation of eager Portuguese envoys expelled from the Portuguese enclave in China, Macau. They wanted to make it clear to all Europeans what they meant. This was the subject of his book “The Christian century of Japan”.

Boxer returned to Japan for two years to a post in the military intelligence section of the War Office between 1935 and 36. There, he told us in 1989, “I had something to do with Anthony Blunt or Anthony Burgess – one of those traitors who were in the Foreign Office, because we had to arrange things over the phone,”

I’m glad Hywel Williams didn’t find this reference to the notorious Soviet double agents in the British government – it would undoubtedly have added fuel to the conspiracy theory. In the middle of the winter of 1937, Boxer was sent to Hong Kong, traveling via the Trans Siberian Railway, Manchuria, Korea, Japan and Shanghai. In Hong Kong, he worked with the Far East Combined Office, a military intelligence unit that traveled throughout China on espionage missions as well as returning several times to Japan.

At the center of Hywel Williams’ accusations of collaboration against Boxer is the period of the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. It involves secret prisoner-of-war transmissions that took place at the Argyle Street camp in Kowloon between British officers and the British Army Aid Group (BAAG), which operated in Chongqing, once the capital of Sichuan province and the base of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist army. The discovery of this “transmitter” by the Japanese in July 1943, Hywel Williams indicates, was the result of Boxer’s betrayal. Only a few officers knew about the transmitter at the time, he says, and all but Boxer were executed.

Professor Alden systematically dismantles these accusations in his March 10 rebuttal of Hywel Williams’ article.

As Alden proves, far from being responsible for the “prolongation” of the Second War, it was Boxer who said that “there could be no greater mistake than to assume, as has been so often done, that the Japanese military were too deeply entrenched in China to turn against us…” It was the British War Office and Foreign Office that ignored and underestimated the risk.

As Alden also points out, Boxer was shot in the back by a sniper trying to raise brainless troops against the invasion. At the Argyle Street camp in Kowloon, information control was key to sustaining morale until the war turned against the Japanese. For a while, this news was available via a secret shortwave receiver (not a transmitter). After the Japanese found it, Boxer and others were arrested, interrogated and sentenced to forced labor. Alden quotes Ralph Goodwin, who escaped from the camp and wrote that Boxer’s fellow prisoners “never ceased to marvel at his incredible strength and calmness of mind.”

After the war Boxer refused a decoration from the British government (an MBE, Member of the British Empire), since he had “done nothing to deserve such an honor”. Later, in 1975, he refused an honor for the second time, the title of Commander of the British Empire (CBE). There was, he said, no empire left to be his commander. Boxer rarely spoke about his time in prison – if ever once. He also refused to write an autobiography. To have been tortured, he told a colleague, was to “share the experience of many of the desperadoes of the past”. Colleagues who went to look for his personal papers found the folders empty. “Always the intelligence officer” was the reaction for a long time at King’s College.

When pressed to talk about this period at the Camões Center interview in 1989, and asked if he had been surprised or apprehensive when Hong Kong fell, he said: “No, I knew that the Japanese, like me, saw clearly what would happen to us. I knew very well that if they treated their own people badly, there was no reason to treat us better. The discipline of the Japanese army was very severe at the slightest mistake. We had seen it all in Japan and I had no illusions.”

Emily Hahn was less reticent about events in Hong Kong during the Japanese occupation. Her voluminous writings and correspondence formed a rich and detailed account of these years. Her book, “China to me”, published in 1944 while Boxer was still a prisoner of war in Hong Kong, dealt explicitly with all the characters – Japanese, English, Chinese and American – with whom she had lived. Her activities and subterfuges, negotiations and difficulties, as well as her relationship with Boxer were shared with 700,000 readers who bought the best-seller.

The “collaboration” that Hywel Williams imputes to Boxer and Hahn was no mystery, nor did it involve treason by any stretch of the imagination.

In fact, it was Hahn’s documents showing that she had a Chinese husband, Sinmay, that saved her, with the connivance of the Japanese consul in Hong Kong, Shiroshici Kimura, who had known Boxer and Hahn since before the war. Hahn recorded this in “China to me”:

“You know I’m American. Everyone knows it. I have an American passport, you know that too.”

“I know.”

“According to American law, this Chinese marriage doesn’t make me Chinese.”

“According to Japanese law,” he said, “it does.”

“You also know that the child is Boxer, don’t you?”

“Of course. Your – hmm – private life doesn’t change the law. You won’t be confined, Mrs. Hahn. In fact, you can’t even be confined. We’re expelling all the Chinese from the concentration camps.”

One of Williams’ most bizarre inaccuracies in his “indictment” is that Hahn was a “feminist and communist sympathizer”, undoubtedly intended to reinforce the idea that Boxer was like the Soviet double agents within the British government, a man prone to betrayal because of his relationship with such a woman.

Ironically, this McCarthist libel, which appeared in The Guardian, parallels the suspicions of American military intelligence when Hahn eventually returned to New York with Carola in December 1943. She was interrogated by eight panels of military intelligence officers and the FBI. Why hadn’t she been confined? Had she been a Japanese spy? Why did she fraternize with high-ranking Japanese officers? Why did she receive “favors” from the Japanese?

Hahn answered only that “in comparison, the freedom I had gained from a lie was important. Not just because the very idea of being confined behind barbed wire was revolting. Outside, I was able to take food and medicine to the camp where Carola’s father was imprisoned. We all did it, a bunch of women whose husbands were in prison. Chinese, Swiss, French, Danish, Eurasian, Russian and me.”

Hahn was undoubtedly a woman ahead of her time in many, many ways, but she made fun of feminists: “Feminists belong to clubs. They collect money for causes. I wish feminists all the best, but I would never want to be one.”

She was too individualistic for such collective causes and, as the late William Maxwell of the New Yorker said, although this hardly needed emphasizing to anyone who had read what she wrote over the years, she liked men. Nor was she left-wing, far from it: during the increasingly bitter split in the United States over China during the last years of the 1940s, she spoke on behalf of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and criticized the communist propaganda that many Americans had, as she put it, “fallen for,”

She dismissed as “stay-at-home experts” those left-wing and liberal Americans who supported the Chinese Communists. In fact, it is precisely because she was neither a feminist nor a New York-style leftist that Emily Hahn is not recognized to this day as the incredible and highly original American she undoubtedly was.

Boxer, of course, went beyond the close ties of British colonial etiquette and entrenched racism.

As Hahn wrote about Shanghai, “The British did not see the Chinese as people. I don’t mean that they didn’t see the Chinese. Of course they did. They spoke of them as peasants, inhabitants of the picturesque villages we passed when we went boating or hunting. They spoke of them as servants, docile, kind… The British community, however, reserved their social life for themselves and those among the Caucasian groups who could be considered acceptable to the upper classes.”

Boxer and Hahn were, of course, just the opposite. They moved in multiracial circles. Hahn had a Chinese lover. And she was American. All these elements obsessed, annoyed and disgusted the British in Hong Kong. And these resentments have obviously not diminished over the years. It is undoubtedly from this poisoned root that gossip was born and ended up in the pages of The Guardian.

As Hahn noted in an excerpt from “China in me,”

“No Englishman thought of inviting Chinese to ‘informal parties.”

Boxer did not tolerate racism, Portuguese or British. A Japanese interrogator during the fall of Hong Kong paid tribute to him when he told Hahn: “Everyone says British bad; Boxer okay. No pride.”

I asked Boxer in 1989 how the British Army reacted to his intellectual interest.

“As long as you hunted and had a horse and that sort of thing you were seen as more or less cool,” he replied.

“If you were interested in history it didn’t matter. If you were interested in the Portuguese or the Dutch, that was seen as reasonably eccentric, but if you hunted and had a horse, those were the most important things.”

In Hong Kong, hunting wasn’t enough. His Japanese connections were no mystery either: it was precisely for this reason that he was placed in an intelligence position in Hong Kong from the start. His Japanese regiment had been one of those that conquered Hong Kong from the British in 1941. The Japanese knew Boxer and he knew them. And he used this understanding to help his fellow prisoners survive.

Unlike Blunt, Burgess and the Soviet double agents, Boxer was no cynic.

His closest friends saw him as a stoic. In his personal copy of Marcus Aurelius’ “Meditations,” he marked the passage on what it is to die as “…he can understand it, not the other way around, see it as the work of nature, and he who fears the work of nature is a child.”

And this stoicism sustained him through everything he went through in those more than three years of captivity, torture and solitude. Was he afraid, we asked in 1989. “No, there was no reason to be afraid. It was part of life. I feel sorry that many of those who died didn’t get to see the end of the war. My friends didn’t live long enough to see it, because they were shot at, killed. I was one of the lucky ones.”

Boxer was no traitor, nor in his own mind was he a hero. He was, as his friend Professor Peter Marshall of King’s College called him, a person with “integrity made of granite.”

When offered decorations, he rejected them.

But one title Boxer could have accepted was the one he liked to quote when talking about Salvador Correa de Sá. For all that Boxer may or may not have been, he was undoubtedly like his 17th century Luso-Brazilian hero: “an old stickler.”

Stickler is defined in my dictionary as tenacious and persistent, someone in search of the truth.

This is something that, at one time, The Manchester Guardian also did.

This article was first published 18 March 2001 on a Brazilian website in Portuguese and unfortunately this website no longer exists.

But the webiste Wayback Machine recovered it and republished it.

And we translated it from the Portuguese back into English.

At the time Kenneth Maxwell was the Nelson and David Rockefeller Senior Fellow at the Council of Foreign Relations, specializing in Latin American studies.