The Australian Government’s Decision on New Landing Craft for the Army

Finally there is some good news in the defence shipbuilding space. On Thursday 24 November, the Australian Government announced that the West Australian shipbuilder Austal would build the Army’s new medium landing craft designed by NSW shipbuilder, Birdon.

That’s good news for three reasons. The first is that this a capability upgrade that Defence urgently needs. The Defence Strategic Review (DSR) envisaged a more mobile Army, able to deploy rapidly to and operate in the archipelagos in our near region.

The Army’s current vessel, the LCM-8, are of Vietnam War vintage and have limited range, seakeeping, speed and carrying capacity and were past their use-by date even before the DSR confirmed the need for something more capable. Moreover, Defence has a massive gap in amphibious capability between the two huge LHDs at 27,000 tonnes LHDs and HMAS Choules at 16,000 tonnes and the humble LCM-8 at around 60 tonnes.

While there was already a project to replace the LCM-8 with the medium landing craft before the DSR, the Review recommended that both it and its larger sibling, the heavy landing craft, be accelerated. It’s good to see that is now happening.

At 500 tonnes, the medium landing craft are still small compared to the LHDs, but they are a big step up from the LCM-8. They’ll be able to carry all of the Army’s vehicles. They’re designed for ‘green’ and ‘brown’ littoral and riverine waters. In essence, the LHDs will carry the amphibious force into theatre, the medium landing craft will move it around in theatre.

But with a range of over 2,000km and ability to operate independently for at least 10 days, these new landing craft will be able to deploy to our ‘first island chain’ by themselves. It’s easy to imagine a small task force of a few landing craft escorted by an Arafura-class offshore patrol vessel operating relatively independently in support of our Pacific Island neighbours on broad range of tasks.

The government has also said it is bringing forward the heavy landing class project from next decade into this one. That’s another good outcome since we’ve had a significant gap in that space since the retirement of the LCH fleet a decade ago.

The second piece of good news is that both the designer and builder are Australian. While Austal is well known, Birdon is hardly a household name here. But it has long and deep experience in designing and building watercraft. Moreover, like Austal, it’s had significant success with customers in the United States, building bridging boats for the US Army and overhauling and building new vessels for the US Coast Guard.

It’s good to see the Government acknowledging the deep expertise and capability of Australian-owned companies that have succeeded in tough international markets. Ultimately this is the point of having an indigenous defence industry; we have capable local companies that understand the Australian operating environment and can design systems to meet the ADF’s requirements.

Moreover, Birdon took on significant risk in its approach to this project. In February this year it began building an actual prototype of its landing craft in Henderson at its own cost. That seems to have allowed it to be able to deliver its solution faster, with Defence saying it will be occur in the ‘quickest and most efficient time frame.’ Putting significant skin in the game has paid off for them. The decision also gets Austal into building with steel, expanding its capabilities.

And this gets to the third piece of good news. When the various contenders for this project announced their bids, Austal and Birdon were not partners. Austal was teaming with BMT and Raytheon to produce a BMT-designed vessel. Birdon’s prototype was being constructed by Echo Marine Group. That’s not where we’ve ended up.

Part of the announcement was that the Government ‘is securing Australia’s shipbuilding capability and investing in Western Australian defence industry through a new strategic partnership between Defence and Austal Limited at Henderson Shipyard.’ What that means precisely is not clear, including whether Austal will be one of or the sole naval shipbuilder in Western Australia.

But in addition to identifying the builder, the Government has also identified the designer it wants and directed them to work together. It’s not letting the market decide who works together. That’s also a good thing. While there is endless discussion about the extent to which governments should ‘pick winners’, it’s unavoidable in the defence sector, particularly in medium-sized economies like Australia.

The market just isn’t big enough to sustain multiple shipbuilders providing the government with a broad range of options every time it wants a new class of vessel. But how do you preserve competition and innovation if the government is constantly intervening in the market? That’s the fundamental challenge implementing concepts like ‘continuous naval shipbuilding’ in Australia. It’s hard to do it well and very easy to get it wrong.

The previous government’s approach has not turned out well. In large part that’s because it started its continuous naval shipbuilding program by ending the only program actually building warships in Australia (the Hobart-cass destroyers)—you don’t get better at building warships without building warships.

But it’s also because it wanted a national continuous naval shipbuilding enterprise, but then ran three separate traditional ‘beauty pageant’ competitions for major war vessels, minor war vessels and submarines. And it’s pretty clear it didn’t like the teaming arrangements that this delivered in the minor war vessel space. This government’s approach is much more interventionist.

And the other reason the previous government’s approach hasn’t gone well is that it believed the key thing to control was the physical infrastructure of the shipyard, so it set up Australian Naval Infrastructure which owns the shipyard in Osborne, South Australia.

But the shipyard itself is the easy bit; anybody with a billion dollars or so can build a very nice shipyard. The hard bit is having the people with the skills to build ships when you need them. And to guarantee that, you need them to be continually building ships.

So it appears that the government may have decided the key thing to have, at least in West Australia which has a lock on minor war vessel construction, is an enduring shipbuilding capability—and that at least a big chunk of that will be Austal. That would mean it will pick the design it likes best, but Austal will build it.

That’s the approach its already signalled it will take on the future heavy landing craft project; Austal has already been anointed as the builder presumptive. As Minister for Defence Industry Pat Conroy said, ‘you need to move faster and partner if we’re going… move the landing craft heavy from first delivery in the mid-2030s to first delivery around 2028.

That meant we had to move away from traditional contracting and procurement methods to say we’re going to partner with Austal, we’re going to partner with a designer.’ There was no statement on the designer, but there won’t be a beauty pageant for the builder.

Economists might not like the idea of picking a winner at this point. But there’s a couple of responses to that. The first is that every country with a naval shipbuilding industry does it; all governments work with enduring shipbuilding partners.

A second is that continuous build should lead to efficiencies in construction. Certainly, there is a lack of competition and competitive tension but Defence has worked with Austal long enough to understand its cost structures; it should be pretty clear if Austal is gouging.

Furthermore, running competitions for the design still offers the opportunity inject innovation and competition into the process.

But while there is good news here, there are still other questions that remain. A big one is what happens to the important capability provided by CIVMEC, West Australia’s other naval shipyard, once its OPV project wraps up.

That could depend on what pathway forward the Government takes with the recommendations of the surface fleet review which was meant to look at options for ‘larger numbers of smaller ships’.

If the government does decide to pursue a light frigate or corvette while continuing with the Hunter-class frigate in Adelaide, noting that’s a pretty big if, considering it will require more money, the only place it could be built is in Henderson.

That will require CIVMEC’s shipyard and workforce, though whether it remains under a CIVMEC label is another question.

So, if the landing craft decision is anything to go by, it’s likely the Government will make an early decision on CIVMEC as the builder, perhaps in some kind of partnership with Austal, but pick its preferred design from the large number of companies already situating themselves for the potential competition.

This article was first published by Strategic Analysis Australia on 25 November 2023.

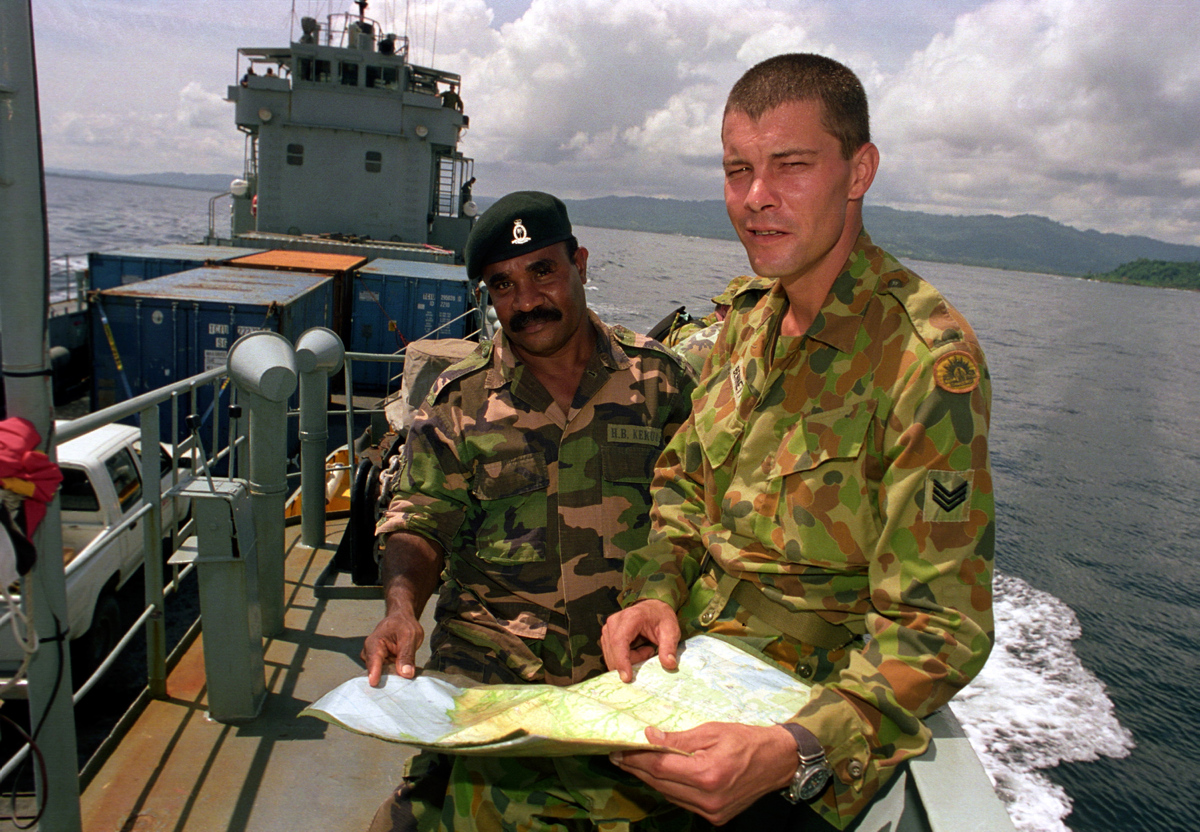

Featured Photo: Sergeant Dave Bennett from the 2nd Battalion The Royal Australian Regiment on board a PNGDF LCH during Exercise Wantok Warrior. Credit: Australian Department of Defence.