The Other 2014 Dynamic: The Migration Crises and Their Impact on the European Union

2014 is a very significant year in the reshaping of Europe and laying the foundations for the next phase of European stability, security and defense.

The seizure of Crimea has set in motion a new effort by European states to provide for their direct defense.

But in the same year, an upsurge in migration from the Islamic Middle East and North Africa has built upon the fissures that were already opening up within the European Union itself.

The twin impact of these two events has been to call into question the approach taken since the end of the Berlin Wall to the construction of a Europe “whole and free.”

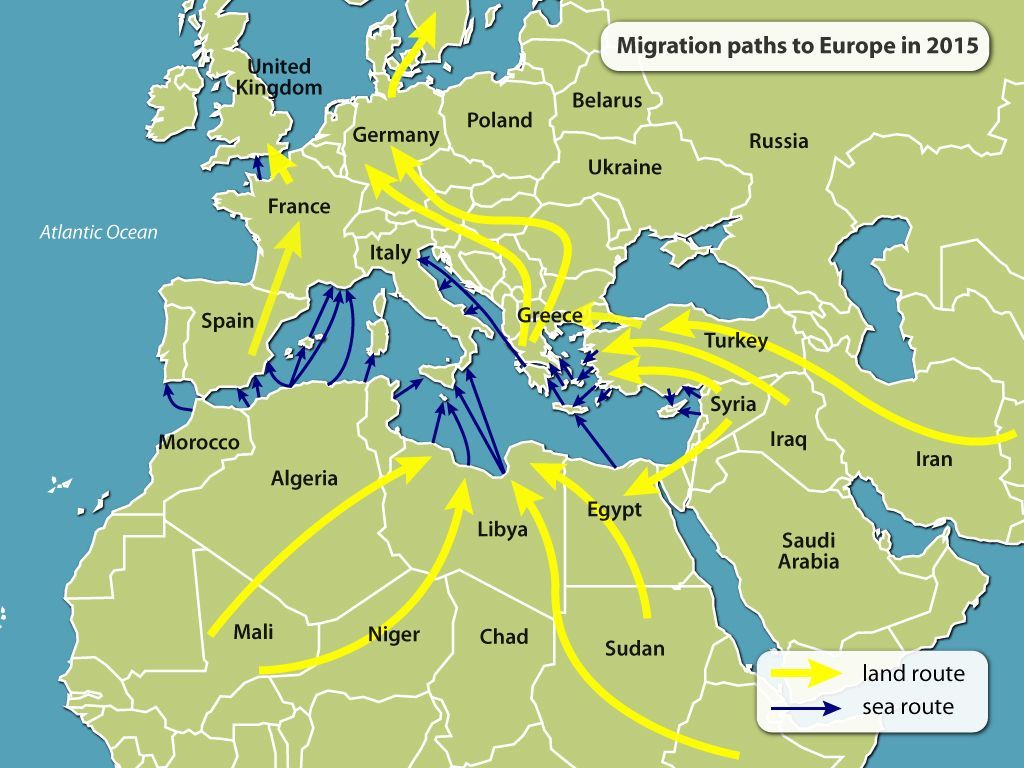

Chaos in Libya, the ISIS wars in Iraq and in the region, the Syrian Civil War and the Iranian build out into the region, all have generated out migration from the region into Europe.

And this outmigration has followed years of change within Europe itself in which Islam has grown as an internal force challenging the secular approach to Europeanization which has characterized the build out of the European Union before 1989 and certainly afterwards. This outmigration has had a significant impact in generating significant conflict within European states and between European states about the European identity, in general, and national identities of European states, in particular.

The return of direct defense in Europe after 2014 is not only having to deal with a Russia quite different from the Soviet challenge, but also having to shape an approach to European development which can account for fundamental national differences with regard to shaping a way ahead for European nations, individually, and as a whole.

The Template for Change in the Struggle for European Values

The template for change generated from the growth of Islam within Europe was already in place prior to the migration shocks from 2014 on. This template was well identified in a classic analysis by Christopher Caldwell entitled Reflections on the Revolution in Europe.

What makes this book especially useful for analyzing the strategic impact of the migration shocks is that it was published in 2007 and had identified how different the Islamic migrations in the post-Cold War period were from earlier experiences.

The European Union was forged in the 1950s in the wake of the dramatic events of World War II. As such, there was a political impetus to work towards a new future, in which war in Europe could be eliminated through the integration of former enemies into a collaborative multi-national working relationship.

The Europeanization which has built from this effort revolves around secularization and the reduced role of Christianity within which was an essentially Christian Western Europe set of societies. European values were equated with secularization and social norms were built around the notion of the inclusion of different national identities within a more universalistic European secular culture.

In this effort to build a European Union, nationalism in terms of protecting the national identity and emphasizing exclusiveness was seen as a negative residuum of a warlike past. As Caldwell put it: “Avoiding another European explosion meant, above all, purging Europe’s individual countries of nationalism, with “nationalism” understood to include all vestiges of racism, militarism, and cultural chauvinism—but also patriotism, pride, and unseemly competitiveness. The singing of national anthems and the waving of national flags became, in some countries, the province only of skinheads and soccer hooligans.”[1]

He argued that the European project was not set up with immigrants in mind, but did set up the rules under which migration would be managed. With the establishment of rules that allowed for the free circulation of Europeans throughout the European Union, the Europeanization effort was accelerated. The notion of migration within the European Union of like-minded Europeans was seen as a key to building not only the European identity by pan-European growth. And indeed, regions have grown in Europe which cross national boundaries, and have created centers of growth and development which have generated the kind of Europeanization which the founders of the European project were hoping for.

But secular Europe was not prepared for the growth of exclusionary communities built around religious commitment. Secularism was a key European value which underlay the European project and allowed for a mellow kind of nationalism to emerge within Europe.

As Caldwell argued: “Had Europeans realized, when immigration from Turkey, Morocco, Algeria, and elsewhere began in the 1950s and 1960s, that there would be thousands of mosques across Europe half a century later, they would never have permitted it. European tolerance of other cultures was sincere, particularly among elites, but not even they anticipated that such tolerance would mean the establishment, entrenchment, and steady spread of a foreign religion on European soil. In exchange for minor economic returns of extremely short duration, Europe replanted the seeds of a threat that had taken centuries of patience and violence to overcome—interreligious discord, both domestic and international.”[2]

With the coming of the internet and of means of communication to allow Islamic migrants to remain deeply connected with their home countries, the notion of pockets of non-secular communities which could affect both domestic and foreign policies of the European Union, built upon secularism became a key reality.

“In Europe, formerly distinct communities’ interests have started to converge into a larger Muslim culture. In most immigrant housing projects, satellite dishes run up the buildings like buttons, picking up the news from home. This would seem to throw into reverse television’s historic role as an engine of immigrant assimilation, keeping open lines of communication from the old country.”[3]

The result in Caldwell’s view was that Europe not only accommodated Islam within their societies but were “for the first time in modern history, European societies were taking pains to allow residents—and, increasingly, citizens—to lead their entire lives in a foreign culture.”[4]

With the rise of a religious advocacy community within Europe which was not anticipated when the European Union was created and European values built on the foundation of secularism, the European project ended up with the absence of tools to allow nations to defend themselves against migration which worked against national identities. “The EU stripped national governments of their capacity to carry out two immigration-related duties—defending borders and defending cultures—while failing to develop that capacity at the European level.”[5]

The system that was established stripped nations of ways to defend themselves against migratory pressures, but put them at the mercy of whatever states would have the most permissive policy to allow migrants in, who then could move throughout the European Union.

This obviously was a policy mix that would become explosive when facing the post-2014 migrations.

As Caldwell underscored: “More often than not, globalization and republican self-rule, of the sort that Europe has enjoyed since the seventeenth century, are at odds. If you want to open your country up to the former, you must sacrifice elements of the latter. Europeans fear their individual countries are slowly escaping their political control, and they are right, although they can seldom spell out precisely how. They sense that Europe is being taken over culturally—whether by theocratic Islam or by a (market) liberalism that accords no particular value to Europe’s most cherished traditions.”[6]

The return of the Russian challenge to Europe is certainly different from that of the Soviet Union, and the migratory dynamics of essentially building of religious enclaves focused on promoting Islam and closely tied by modern means of travel and communications technologies to their former communities is also distinctly different from the period from the 1950’s through the 1980’s when the West was battling Soviet communism.

Caldwell highlights this difference in very cogent manner. “Empathy among Muslims creates a big potential problem that does not exist with other immigrations. Imagine that the West, at the height of the Cold War, had received a mass inflow of immigrants from Communist countries who were ambivalent about which side they supported. Something similar is taking place now. European countries have lately been at war with Muslim forces in Iraq, Afghanistan, the Balkans, and Africa; and this is leaving aside countries of European culture, such as the United States and Israel, that are fighting similar battles.”[7]

The template which Caldwell describes was already in place when the 2014 migratory dynamics unfolded.

The Major Impact of the 2014 Migration Crises[8]

The migration crises, due to its multiple trigger points, should not be considered as only one crisis but as many that intertwine and currently impedes European progress to move forward. The major influx of new migrants from the War-Torn Middle East and North Africa originating in 2014, has generated a major blow to the evolutionary process of evolving European integration.

This is an issue that places into question the borders as well as the security and the composition of Europe as a whole. With member states significantly differing on what it means to take responsibility for the influx of migrants that are fleeing war-torn countries and are seeking asylum in Europe, migration is a problem that will affect the politics as well as the demographic and composition of Europe for the period ahead.

In 2015 alone, “one and a quarter million refugees applied for asylum in the Union… twice as many as the year before.”[9] The sheer number of immigrants that flooded European shores overwhelmed European policy makers in Brussels. And the gap between what nations wished to do versus how Brussels sought to manage the overall process is a wide one. Brussels was blind to the “gap between what was administratively possible and what was… politically required.” [10]

In response to the political lag in Brussels, two of the central tenets of the European Union have been highly criticized and deemed necessary to reform: Schengen and the Dublin Regulation.

Schengen, or the ability to travel freely within the 26 states that participate, is symbolic to a common and united Europe and yet with the issues of border security and lack of migration control it has come to be increasingly scrutinized.

A key aspect of ongoing efforts is focused upon: Schengen “would benefit from being updated” and that many have “lost track of how its borderless area should work” from a security perspective.[11]

Another aspect that many have requested, especially those in the Southern states, is to update or replace the Dublin Regulation which establishes that whatever EU state an asylum seeker enters first, that state is responsible for its asylum application. “The current Dublin asylum Regulation has failed us—it induced a race to the bottom; whereby European states compete to become the least attractive for migrants” which has created an absolutely divisive political atmosphere.[12]

Migration also poses an identity threat to the European Union, “asking distinct nations to give up part of their identity for a larger, common European identity could have worked if a European identity had been established during the advent of Union itself” but what it means to be European does not have one single answer across the 28 (and after Brexit, 27) member states.[13]

The November 2004 European Council agreement on “common basic principles” provided an array of integration policies offered for facilitating the process of migrants setting in Europe. One of these policies is written as to what is expect on behalf of migrants: “‘Integration implies respect for the basic values of the European Union.”

What are these values?

When one looks at the Caldwell template, it is precisely the question of values which are in play and the future of secularization as a foundation for Europeanization.

This disagreement on what it means to be European has led to a wider ‘identity crisis’ that is being felt across Europe and reflected within society and the politics that people are turning to.

Migration is an issue that is multifaceted: it can be considered on a human level, an economic level, a political and a security level.

In politics, Brexit is a prime example as to how the migration crisis has helped shape the political narrative. The inability to shape a European consensus on how to deal with refugees contributed to what had more conservative voters eager to vote “YES” to leave the EU.

This is also part of a larger wave in surge of right-wing parties and voters, “the League in Italy, the Alternative fur Deutschland in Germany, the Rassemblement National in France and now Vox in Spain.”

With regards to the economy, the migration crisis places further financial burden on economies that were weakened by the Eurozone crisis. Greece for example, the main victim (and some argue, perpetrator) of the Eurozone crisis, took the majority (alongside Italy) of the arriving migrants but over the past five years, agreements for distributing migrants have been worked within the European Union. Due to the Dublin Regulation, asylum seekers must apply for asylum in Greece if that is their country of origin- a country that does not have the economic backbone to support this increase in population.

This crisis also affects the Russia threat because it plays into a further disintegrated and chaotic Europe that the Kremlin takes advantage of. Meddling in European elections and pushing support for the right-wing candidates, Russia is very aware of the migration threat that is pressuring European unity and collaborative capabilities.

Indeed, Russia’s own engagement in Syria has not played a positive role upon reducing the threat but has accelerated it.

The featured graphic is credited to the following source:

[1] Christopher Caldwell, Reflections on the Revolution In Europe: Immigration, Islam and the West (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition), 83.

[2] Caldwell, “Reflections on the Revolution In Europe, “ 111-112.

[3] Caldwell, Reflections on the Revolution In Europe, 160-161.

[4] Caldwell, Reflections on the Revolution In Europe, 166.

[5] Caldwell, Reflections on the Revolution In Europe, 303.

[6] Caldwell, Reflections on the Revolution In Europe, 329

[7] Caldwell, Reflections on the Revolution In Europe, 162-163.

[8] This section has been written by Chloe-Alexandra Laird

[9] Luuk van Middelaar, Alarums & Excursions: Improvising Politics on the European Stage (Newcastle upon Tyne, Agenda Publishing, 2019), 91.

[10] Luuk van Middelaar, Alarums & Excursions, 92.

[11] Raoul Ueberecken, “Schengen Reloaded.” Centre for European Reform, November 11, 2019, www.cer.eu/publications/archive/policy-brief/2019/schengen-reloaded.

[12] “How to Solve Europe’s Migration Crisis,” Politico, February 8, 2016, www.politico.eu/article/solve-migration-crisis-europe-schengen/

[13] Alessandra Bocchi, “Why Is the European Union Failing?” Human Events, May 3, 2019, https://humanevents.com/2019/05/02/why-is-the-european-union-failing/?fbclid=IwAR22XHeJYKraU891YK-Y-3LMKvINEzpdJoVpXXKZS9bWcjsv7tdlXldrzJM