Australian Defence Force Embraces Long-range Fires

It’s a fact: in any conflict the fighter with the longer reach has a definite advantage. The Australian Defence Force is trying to create that advantage for itself by spending up to $27 billion on 12 new families of long-range missiles between now and 2034 and investing another $21 billion in manufacturing at least some of them in-country.

And it plans to spend another $7.3 billion developing what April’s Integrated Investment Program (IIP) calls a Defence Targeting Enterprise to detect, identify, track and allocate weapons to those targets, engage them and then carry out post-strike reconnaissance. Essentially, the ADF is looking to go beyond the rhetorical limitations of the ‘Kill Chain’ and establish a ‘Kill Web’ which enables it to address a much wider area than hitherto. More about this below.

Some of those missiles and targeting systems are coming together this calendar year: the first of four Northrop Grumman MQ-4C Triton High Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) Uncrewed Air System (UAS) ordered by the RAAF has just arrived at RAAF Base Tindal in the Northern Territory. The first of the Kongsberg Naval Strike Missiles, which will replace the venerable Boeing AGM-84-series Harpoon that arms the RAN’s Hobart-class destroyers and ANZAC-class frigates is also due to arrive in 2024. And the first Australian-made GMLRS rockets will be flight tested in 2025, with a batch of US-made GMLRS and their HiMARS launchers entering service at around the same time.

The implications of this dramatic extension in strike range are significant. If it gets this right, the ADF will be able to hold an aggressor at risk at some distance from its home soil and its own forces; but it also needs to refresh both its targeting systems and its diplomacy to reflect its much greater reach and impact. This is all consistent with the ADF’s transition from a balanced force to an integrated force and a new defense strategy of Deterrence through Denial.

However, those long-range weapons aren’t in service with the ADF yet. At present, Army’s reach is about 30-40km using conventional artillery; the RAN’s reach is 170km using the SM-2 anti-air and -missile weapon, or about 125km using the anti-ship Harpoon Block II.

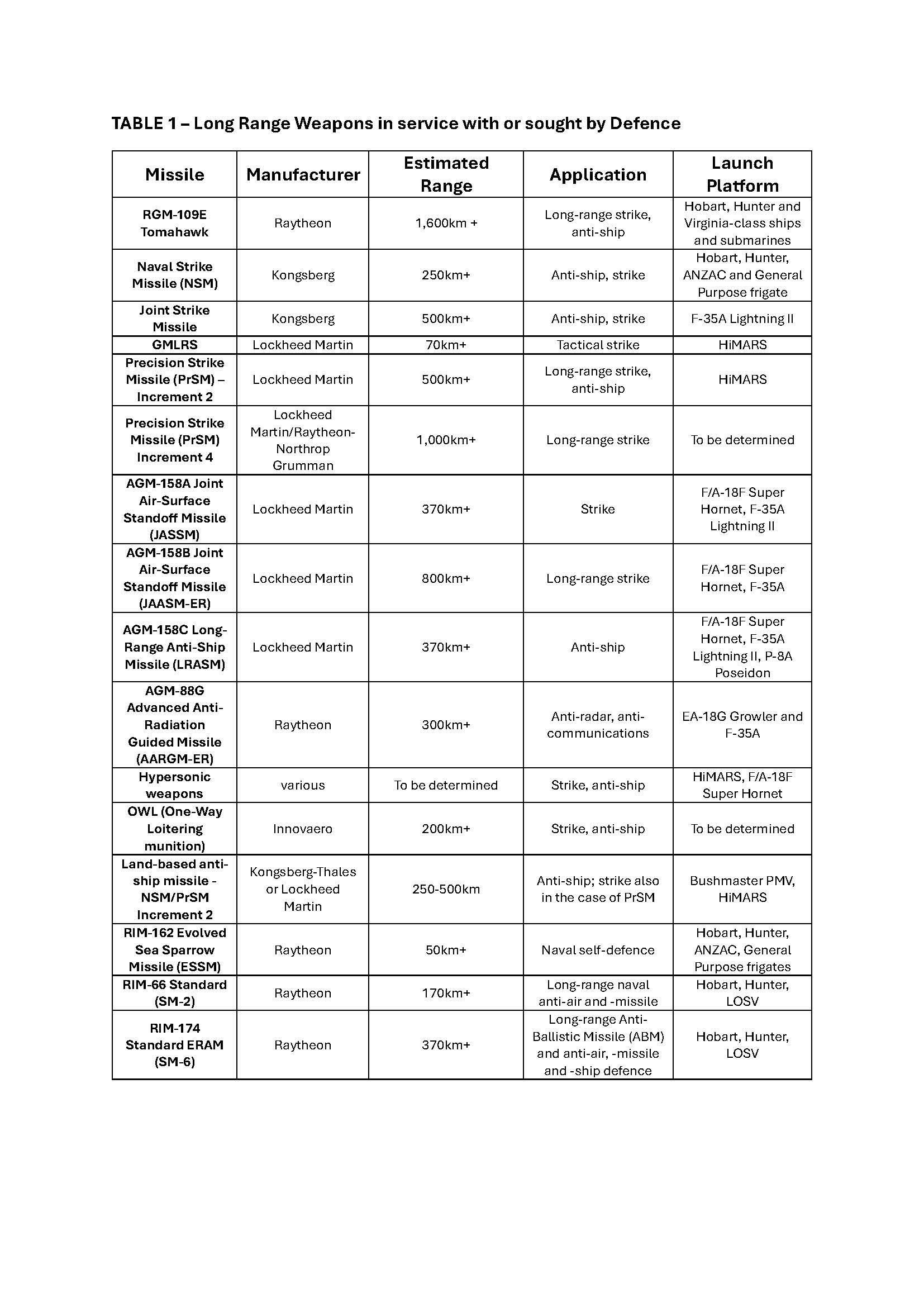

Table 1 lists the long-range weapons currently in service with and sought by the ADF. Except for the Lockheed Martin GMLRS and some naval anti-air/missile weapons, the minimum range of the new generation of missiles is 200km.

Only the RAAF currently has a genuine long-range strike weapon, Lockheed Martin’s AGM-158A Joint Air-Surface Stand-off Missile (JASSM) which arms the service’s F/A-18F Super Hornets and P-8A Poseidon patrol aircraft and has a range of more than 370km. This stealthy weapon entered service in 2006 (it will be supplemented, and then replaced, by the AGM-158B Extended Range version of JASSM which has an 800km range) and has given the ADF some valuable experience of targeting a weapon with such a range.

The RAN and RAAF launch platforms and their general organisation won’t change when these services field the new weapons. But the Army has begun a significant transformation to operate this new generation of stand-off missiles. The long-established 16th Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery (RAA), operates the Saab RBS-70 point defence missile; from next calendar year this will be replaced by the eNASAMS (enhanced National Advanced Surface-Air Missile System) acquired under Project LAND17 Ph.7b. Primed by RTX subsidiary Raytheon Australia, this will blend the proven Raytheon AIM-120 AMRAAM and AIM-9X missiles and Kongsberg launchers with the CEATAC and CEAOPS phased array radars manufactured by Australian company CEA Technologies.

The 16th Regiment will be part of an all-new formation, the Adelaide-based 10th Brigade which was formed in January 2024 and whose focus is on long-range fires and air and missile defence. From 2025 the Brigade’s new 14 Regiment will operate 36 HiMARS launchers, acquired from Lockheed Martin under a US Foreign Military sales (FMS) agreement, firing the GMLRS and its extended range variant. The remaining six launchers will be used for training. The capabilities of the Brigade’s planned 15 Regiment, its launchers and projectiles, are still under Defence consideration; they will be delivered under Project LAND8113 Ph.2.

In due course (Defence hasn’t said when) 14 Regiment will also operate Increment 2 of Lockheed Martin’s Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) which has a range of 500km. And Australia is a partner in developing the PrSM Increment 4 missile which is still under development (Lockheed Martin is battling for this contract with a Raytheon-Northrop Grumman consortium) and will have a range of 1,000km.

The Australian Army also has a requirement for 30 land-based anti-ship missile systems to be operated by the 10th Brigade, originally under Project LAND4100 Ph.2 – Land-Based Maritime Strike. However, the Brigade’s first land-based maritime strike capability will be delivered by 14 Regiment’s HiMARS launchers, GMLRS and PrSMs under Project LAND8113. Phase 2 of this project will also see the Brigade’s new 9 Regiment operate an undisclosed number of advanced radars – probably CEA Technologies’ CEATAC and CEAOPS sensors.

While PrSM may eventually be able to hit moving targets such as ships, Kongsberg and Thales have spotted an opportunity and combined to offer the NSM-based Strikemaster anti-ship and strike system. This would see the missile fired from the same ‘twinpack’ launcher used in Kongsberg’s proven Coastal Defence System and mounted on the ‘pickup’ version of Thales’s Bushmaster wheeled armoured vehicle. Except for the Bushmaster, this is also very similar to the US Marines’ autonomous, uncrewed Ground-Based Anti-Ship Missile system which uses the NSM with the same twinpack launcher.

The NSM has a 250km range from a ground or maritime launcher and will arm the RAN’s three Hobart-class destroyers and six remaining ANZAC-class frigates, its six future Hunter-class frigates and possibly also its planned fleet of up to 11 General Purpose frigates. So, the Strikemaster looks a low-risk option for the ADF.

The RAN’s long-range weapons will be the NSM, SM-2 and SM-6, and the RGM-109E Tomahawk strike missile. The latter has a range of more than 1,600km while the SM-6 has a range of around 370km.

The RAAF’s air-launched strike inventory started with JASSM; its reach will grow with Lockheed Martin’s JASSM-ER (800km range) and the AGM-158C Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM – 370km range); the Northrop Grumman AGM-88G Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile (AARGM – 300km range); and possibly the Kongsberg Joint Strike Missile (JSM), the air-launched variant of NSM, which has a 550km+ range and has just been ordered by the USAF for its own F-35As. The JSM can be carried internally to preserve platform stealth. (In each case, range figures depend on the flight profile followed by the weapon).

These weapons will be carried by the RAAF’s combat aircraft, the Super Hornet, EA-18G Growler, Lightning II and P-8A Poseidon patrol aircraft.

There’s another contender also: Northrop Grumman is partnered with Raytheon Technologies to develop the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HACM) for the US Air Force (USAF). HACM is reportedly a first-of-its-kind weapon developed in conjunction with the Southern Cross Integrated Flight Research Experiment (SCIFiRE), a US-Australia project arrangement. Raytheon Technologies and Northrop Grumman have been working together since 2019 to develop and integrate Northrop Grumman’s scramjet engines onto Raytheon’s air-breathing hypersonic weapons.

Defence targeting enterprise

Targeting for these weapons is the ADF’s new challenge and one of the keys to effective deterrence..

Defence needs to be able to detect, identify and track targets for its weapons; it may then need to indicate the target to a missile; and after the attack it needs to carry out post-strike reconnaissance to establish whether the target was actually hit and, if so, how badly it was damaged.

That bald statement of targeting principles barely describes the complexity of the targeting process. A sensor that detects and tracks a target isn’t enough: they all need accurate positional data and, in the case of weapons with a moving target capability, information about the speed and direction of travel of the target. And the ADF needs corroborating intelligence and continuous situational awareness in order to determine what not to shoot at: the reputational damage, not to mention the financial and opportunity cost, of striking the wrong target may be massive.

This is what the IIP had to say in Chapter 5 about its planned Defence targeting enterprise:

5.2 An advanced and resilient network of sensors and communications and intelligence systems will be brought together to form a Defence targeting enterprise. The Defence targeting enterprise will provide Defence with the timely ability to detect, identify and track targets more precisely and at longer ranges in highly contested operating environments. The Defence targeting enterprise will be underpinned by a highly trained workforce and will be interoperable with the capabilities of the United States and other key partners.

The IIP allocates up to $7.6 billion to this program.

Defense.info asked Defence for further information about the Defence Targeting Enterprise, in particular whether or not a new HQ would be established within the ADF just to handle targeting. The response was unequivocal: the Defence Targeting Enterprise will not be a separate command within the ADF or wider Department of Defence. “Targeting,” we were told, “will remain a process that is undertaken by commanders at different levels, enabled by the effective integration and augmentation of supporting capabilities.” In response to Defense.info’s questions a Defence spokesperson said:

Targeting is an activity that has long been undertaken by Defence at different operational levels and in a variety of settings. Many organisations and systems contribute to it. The direction to establish a Defence Targeting Enterprise reflects a focused effort to modernise and enhance capabilities that enable the targeting process, ensuring they are optimised to support new long-range weapons entering service and the demands of an increasingly complex operating environment.

The Defence Targeting Enterprise is not a specific organisation that will be established in a particular place. Rather, it will be a federation of integrated organisations, systems and processes across Defence that, collectively, will allow selection and prioritisation of targets and match them with appropriate responses. This approach recognises growing interdependencies between different elements of Defence during the targeting process and will allow greater assurance of system efficacy. Many elements that will contribute to the Defence Targeting Enterprise already exist and will be modernised or enhanced. Other elements will need to be created or adjusted in coming years. This will not occur in a singular location and will evolve over time.[1]

In a separate email, a Defence spokesperson added:

Detection capabilities and the ability to sense underpin strike and IAMD capabilities. To enable the integrated, focused force to conduct enhanced long-range strike, Army will draw from an advanced and resilient network of sensors and communications and intelligence systems through the Defence Targeting Enterprise, including multi-mission phased array radars. 9 Regiment [of 10 Brigade] will operate advanced radars that will be acquired through the second phase of Land 8113 to provide an organic sense capability. This will be complemented by 10th Brigade’s technical integration as a component of the Defence Targeting Enterprise, capable of providing and receiving target details from the broader force. [2]

As stated earlier, the ADF has been developing a stand-off targeting capability since it selected JASSM in 2006. Details are scarce, but the ADF’s targeting resources will eventually include four (and possibly seven) Triton UASs with radar and infrared sensors; space surveillance sensors; the Jindalee Operational radar Network (JORN); radars and infrared sensors on the P-8A Poseidon and E-7A Wedgetail; MC-55A Peregrine ISREW aircraft; warships and their helicopters; Super Hornets and Growlers; F-35A Lightning IIs and all sensors operated by 10th Brigade. These all contribute to Situational Awareness but are also target detectors and trackers. The power to actually prosecute a target, however, will still reside in the hands of men and women – aloft, afloat or in a headquarters or command post somewhere.

The RAAF’s first Triton is in-country. The RAAF has ordered four but really needs all seven it says it wants in order to field a robust capability. From an altitude of 55,000ft Triton has a radar horizon of more than 500km so its Over The Horizon (OTH) targeting capabilities are immense. Its mission endurance of as much as 30 hours also enables it to surveil up to 4 million square nautical miles of sea or littoral in a single mission. While the P-8 and the RAN’s MH-60R Seahawk helicopters can also do surveillance and OTH targeting, they are limited in both time and operating area and can be re-tasked as contingencies emerge or change – Triton offers genuine persistence.

However, all three will feed into the Defence Targeting System: a naval contact spotted by a Seahawk, for example, could become a target for a land-based anti-ship missile; a fixed piece of land-based infrastructure monitored by successive Triton orbits could result in a Tomahawk cruise missile attack launched by a submarine.

‘Kill Web’

And this is where the ADF seems to be starting to embrace the concept of the ‘Kill Web’: taking target information from intelligence sources and sensors right across the ADF and the wider Department of Defence, matching targets with the most appropriate effectors (regardless of who operates them) and then attacking the target in the most effective way the circumstances allow. A node that seems well suited to this task is the Joint Air Battle Management System (JABMS) for which Lockheed Martin has just signed the prime contract under Project AIR6500. But JABMS isn’t the only potential node in this ‘Kill Web’ – each of the three services and Joint Operations Command can play a significant role depending on the threat, the target and the choice of weapon.

You obviously need good voice and especially data communications to make it work; and you increasingly need Artificial Intelligence (AI) to react quickly to sudden threats or fleeting opportunities. However, in the Australian context the AI will mostly present information to a human decision-maker because, at the end of the day, Australia’s ethical approach to the use of AI and autonomous systems in combat demands that it’s still a human being who makes what might be a life-threatening decision.

The targeting function and necessary communications – Link 11, Link 16, Link 21 and 22, SATCOM etc, with appropriate capacity – need to be embedded in warships, deployed land force HQs and multi-role aircraft such as the P-8A, E-7A and MC-55A. Apart from anything else they need the autonomy to be able to engage or evade incoming missiles, for example, or to simply get on with their jobs. But the ADF’s Defence Intelligence Organisation also needs to be involved for strategic and static targets such as dockyards, enemy HQs, fleets of ships and aircraft, and even satellites.

The implication of all this for the ADF is significant. In purely defensive terms, it can see further: it can spot and react to incoming weapons earlier. In an era of hypersonic missiles this matters.

But its longer reach and ability to target its weapons accurately at whatever range they can achieve also means that the ADF can make its impact felt across a much wider area. To east and west, where a potential aggressor must come across the sea or try to disrupt undersea cables, the ADF can dominate a much greater area than has been the case hitherto.

To the north and northwest of Australia lie ten separate sovereign nations – not including China – in most of which the ADF could conceivably deploy in support of a friendly government or to face a common threat. Go just a bit further afield and that number climbs to 16 nations. The ADF’s combination of land-, air- and sea-launched weapons could inflict an unacceptable price on anybody attempting to misuse adjacent sea areas or a contiguous land mass.

The Australian Army’s reorganisation has seen its light, Darwin-based 1st Brigade focus on littoral operations, with its much heavier Townsville-based 3rd Brigade focussed on amphibious operations – indeed one of its units, the 2nd Bn Royal Australian Regiment, is effectively Australia’s amphibious battlegroup.

The clear implication is that either Brigade (depending on the terrain) or possibly both could deploy into Australia’s northern archipelago and support allied and friendly governments tackling a common threat. A long-range fires (including land-based anti-ship) capability would enable island-hopping, if such a thing were necessary, and would also extend Australia’s, or an ad hoc alliance’s, deterrent range much further than is currently the case.

A strategy of Deterrence through Denial is enabled by weapons with a long reach, a strong, well-equipped ADF and a demonstrated willingness to use it if necessary. These are best deployed in support of Australian statecraft, including diplomacy.

This is where the Department needs to be part of a broader national security strategy, which Australia has lacked for too long. The Australian government’s civil and military capabilities need to complement each other, and they must be robust and transparent. They are none of these things – at least visibly – at present.

[1] Defence email to author, 22 May 2024

[2] Defence email to author 20 June 2024

Featured Photo:

Arrival of Royal Australian Air Force MQ-4C Triton Remotely Piloted Aircraft System at RAAF Base Tindal in the Northern Territory. Australias first MQ-4C Triton Remotely Piloted Aircraft System arrived on home soil June 16, 2024 at RAAF Base Tindal in the Northern Territory. The MQ-4C Triton is a high altitude, long endurance, remotely piloted aircraft system, which will provide long-range, persistent surveillance across Australias maritime approaches and its broader areas of interest.

The MQ-4C Triton fleet will be based at RAAF Base Tindal, Northern Territory, and operated by Royal Australian Air Force Aircrew of the reformed Number 9 Squadron at RAAF Base Edinburgh, South Australia. Once in service, the MQ-4C Triton and the P-8A Poseidon aircraft will operate as a “family of systems” to provide Defences Maritime Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) capability.

Defence will continue to work with industry to support our workforces, to deliver the priorities and capabilities our nation requires to protect Australia and its national interests.

Credit: Australian Defence Force

For more on the issues raised in this article, see our recently released book on Australian defence:

Also see our book on the kill web which featured the coming of the Triton to the ADF on the cover: