The Pivot: The Portuguese Coup of the 25th April and its Global Consequences

On Friday 25 October 2024, Dr. Kenneth Maxwell gave the keynote address in Lisbon at a conference on the international dimensions of the Portuguese transition. It was hosted by the Fundação Oriente. The address by Dr. Maxwell follows.

I would first like to the thank the Instituto Portuguese de Relações Internacionais of the Universidade Novo de Lisbon, the Fundação Oriente, and the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, for organizing this important meeting. It is a great honor to be here and to be among such a distinguished gathering of Portuguese and international scholars. I am anticipating learning a great deal from the presentations and discussion.

In February 1974 I was at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. I had been appointed the Herodotus Fellow in the School of Historical Studies in 1972. But I had remained at the Institute for a further three years with the support of a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. I was working at the time on the late 18th Century Atlantic revolutions, and in particular on the great slave revolt which took place in the French Caribbean colony of Saint Domingue, which later was renamed Haiti.

I had lived in Portugal in 1964 for almost six months where I had received the very welcome support of the Gulbenkian Foundation. As a consequence, I had some very close friends in Portugal from that time. I had visited them and stayed with their families, especially in the north of Portugal, several times over the intervening years. When General Antonio de Spinola’s book Portugal and the Future was published in Portugal in February 1974, I thought that something serious was taking place.

General Spinola had been the commander-in-chief in Portuguese Guinea and was the vice-chief of staff of the Portuguese armed forces. His book was clearly a challenge to the leadership of Marcelo Caetano, who had succeeded Salazar as the political leader of the Portuguese State. I contacted Robert Silvers, the editor of The New York Review of Books, and said as much to him. He was convinced that something serious was afoot in Portugal and he gave me press credentials to go to Portugal to investigate.

I went to Portugal via London. A friend was at the time a senior editor at The Economist. He gave me access to the press clippings collection at the London Library on St James Square. I spent a couple of weeks going over all the press coverage of Portugal. I also contacted several Portuguese exiles living in England. At the time, the press clippings collection at the London Library provided an overview of what the international press was saying about Portugal: Very little as it turned out. I also meet Robert Moss, the editor of The Economist’s “special report” which was a confidential report sent to paying clients.

But I was warned by my friend to be cautious with him: Very good advice as it turned out. I then spent a month in Lisbon. One of my closest Portuguese friends from 1964 was a miliciano officer based in Lisbon. In fact, the tension between the miliciano officers and the regular officers in the junior officer corps had been one of the causes behind the formation of the “armed forces movement” comprised entirely of the later.

I met with only foreign correspondent In Lisbon at the time in the week before the coup in the bar at the Tivoli Hotel. Bruce Loudon was the stringer for The Daily Telegraph in Lisbon. He had been fired by The Financial Times in 1973 for his closeness to Portuguese government officials and he had long been an apologist for the Portuguese regime. Loudon had denied the Wiriyamu massacre by Portuguese troops in Mozambique, denounced by the British Catholic priest, Father Adrian Hastings, had taken place at all. Bruce Loudon had told Dr. Pedro Feytor Pinto, the Director of the Portuguese Information Service (it was revealed after the coup) that though he was “only a humble foreigner …I shall help on any way I can.”

Needless to say, London knew nothing at all about the impending coup a week later. But I was by then used to Portuguese disinformation. I had written a piece for The New Society in June of 1964 entitled “Date Line Lisbon.” In the article I described an attack on a mass protest demonstrators by the police in Lisbon’s Rossio and Restauradores outside the Rossio station. It was denied by a pro-Portuguese letter writer saying I had made the whole thing up. But I had in fact actually been there. I was reporting on real events, and I had witnessed the shooting of one of the protesters.

The hotel lobbies in Portugal in early April 1974 also prominently displayed an article by George Kennan. George Kennan, who I knew from the Institute for Advanced Study, had been the American charge d’affaires in Lisbon during WW2, and was a staunch defender of the role of the Portuguese in Africa. In fact I had sat opposite George Kennan at the first dinner on my arrival at the Institute where he had mused that only “the Teutons” had a historical sense. But Kennan was not alone, Dean Acheson, the U.S. Secretary of State in 1950, had observed about Salazar, the long-term Portuguese dictator: “A libertarian may properly disapprove of Dr. Salazar, but I doubt whether Plato would.”

George Kennan had also negotiated while Charge d’Affaires in Lisbon in 1943 the American access to the Azores base under the cover of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance (the Azores base was critical to anti-submarine activity in the Atlantic). Salazar had obtained a critical quid por quo from Washington which committed the United States to respect the territorial integrity of the Portuguese colonies in return for access to the Azores facilities. The growing role of the U.S. In international affairs was deeply distrusted by Salazar. George Kennan told the Secretary of State: “Salazar .. has as much fear of associating with us as he does with the Russians.”

Marcello Caetano believed that the problems of discontent in the middle ranks of the officer corps had been dealt with, that a plot by a leading right-wing general had failed, and the uprising of the fifth infantry battalion at Caldas da Rainha had been rapidly contained by loyalist army units and the Republican Guard. He was more worried in April 1974 about the prospects of labor unrest by industrial and office workers in May, the usual month of labour militancy.

The Portuguese secret police on the 24 April, 1974 coup, moreover, had taps on the phones of General Spinola, General Costa Gomes, Major Melo Antunes, Captain Vasco Lourenço, and General Kaulza de Arriaga, who had attempted to organize a right wing coup and had failed, as well as on that of President Américo Tomas, and also, bizarre as it may seem, on the prime minster Marcello Caetano himself. Caetano had intended take a decision on a general pay increase for the whole officer corps on the day of the coup.

A year earlier, on the 11 November 1973, in Chile, General Augusto Pinochet had carried out his bloody coup against the elected president Salvador Allende. Only six months later when the military coup took place in April in Portugal, most expected that a military coup would come from the right. That had been the pattern in southern Europe and in Latin America: In Spain since the victory of Generalissimo Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War; in Greece under the regime of the colonels since 1967; and in Latin America since the Generals in Brazil took over in 1964 and Pinochet took power in Chile in 1973. This had been the pattern: Military coups came from the right.

Yet In Lisbon in April 1974 the military coup d’etat came from the left and was not carried out by generals but was led by the captains. As one member of the MFA said at the time: “After fifty years of right-wing dictatorship where else would it come from.”

This was the most difficult thing to explain to outsiders in the immediate aftermath of the 25 April coup and it explains why it took outsiders many months to realize where power lay in Portugal. No-one outside Portugal, and many within Portugal, knew any of the young Captains who constituted the Armed Forces Movement (MFA). As the American defense attache said “I never spoke to anyone below the rank of colonel.” Cord Mayer, the CIA station chief in London, said in 1974: “When the Revolution took place in Portugal the United States had ‘gone out to lunch’. We were completely surprised.”

But Cord Mayer, a CIA official, had made one very important point in his comment. “What had happened in Portugal was a “revolution.” It was not as many now claim a “transition.”

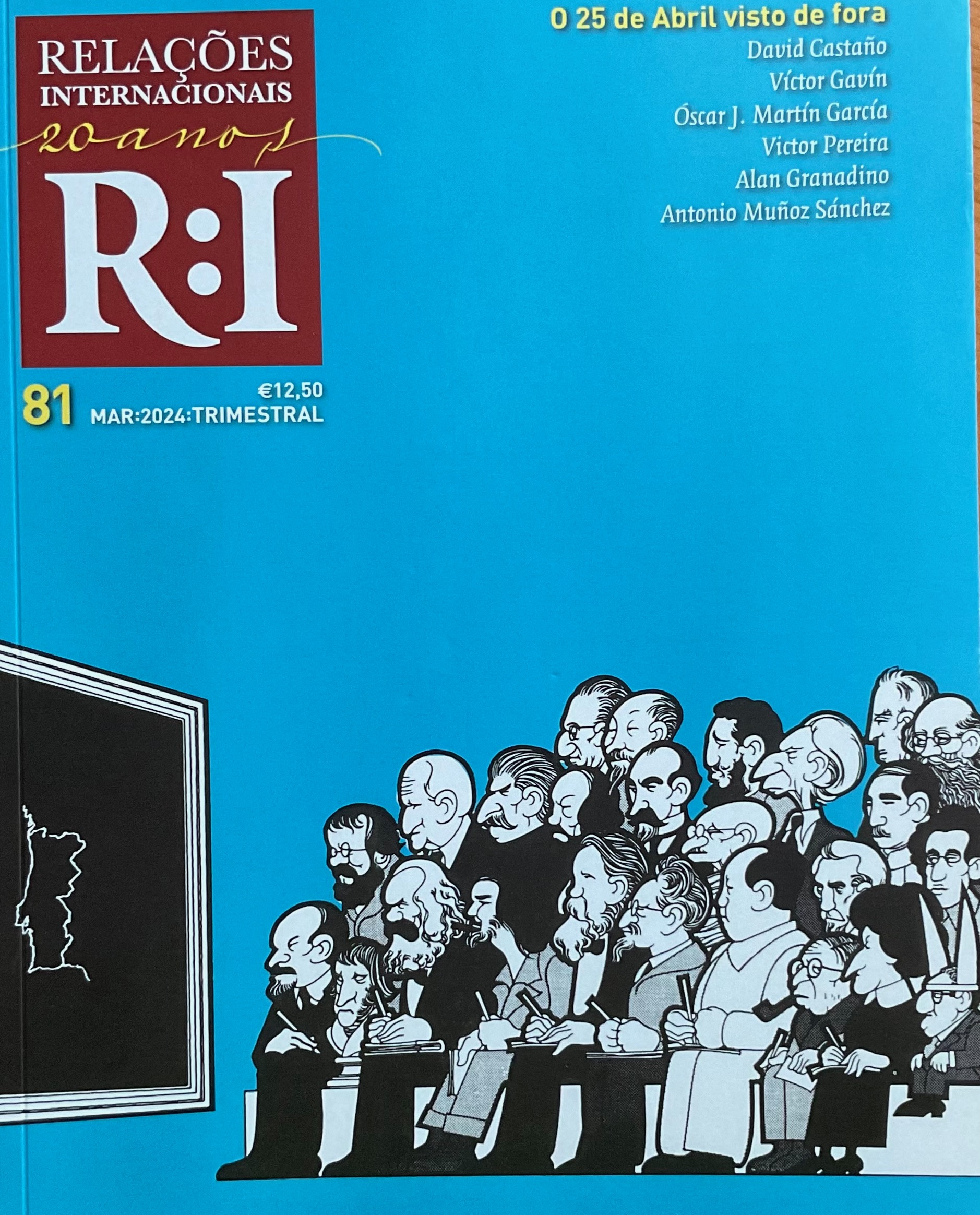

The excellent series of articles in the most recent issue of R:I Relações Internacionais do IPRI-Nova “o 25 de April visto de fora” covers much of the international reaction to April 25th in the U.S., in Great Britain, in Paris, in Spain, and in West Germany. (The cover is the featured image for this article.)

Today we will hear about the reaction in Italy, the only democracy in southern Europe at the time of the coup in Lisbon.

But in the marvelous poster of Joao Abel Manta from 1975, which adornes the cover of the issue, it was not Marx, Lenin, Stalin, Bernard Russell, or Ho Chi Minh, all dead at the time, that were among those thoroughly galvanized by events in Portugal.

In fact, it was two very much alive individuals standing (or sitting) among the rest of the puzzled observing of Portugal in Joao Abel Manta’s poster. They were to have the most influence in the months following the coup: Fidel Castro standing in the top row, and a midget Henry Kissinger, tucked away in the far-right lower cover of the poster, perched with his legs dangling, and with devils spikes strapped around his head. The Brazilians are also totally absent from Joao Abel Manta’s depiction, yet they would also have a major role in the reaction to the 24 April and most especially during the “hot” summer of 1975.

What had happened in Portugal was the total collapse of the old regime.

Portugal was in fact had become a critical pivot where many of structures which had emerged in the post WW2 world shifted.

In the Middle East because of the American bases in the Azores which had been critical to the American resupply of Israel during the Yom Kippur War, and the consequent rise in the price of petroleum from the Persian Gulf, and the closure of the Suez Canal; in Southern Europe because the rule of the right wing military was challenged by the sudden collapse of the the long lived Portuguese dictatorial regime.

In East-West relations where Washington and Moscow were engaged in a policy of detente.

In the U.S. where after the resignation of Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger had assumed almost absolute power over U.S. foreign policymaking as national security adviser and Secretary of State under in the first tentative first year of the presidency of Gerald Ford.

In Chile and Brazil where regimes had been put in place with the covert assistance of the United States.

In Southern Africa where the Portuguese colonial territories of Mozambique and Angola with the massive intervention of the Portuguese army had held the line for the white ruled states of Rhodesia and apartheid South Africa where institutional racial segregation was imposed.

Moreover, Portugal was about to experience the last real revolutionary upheaval in Western Europe. The end of censorship, the release of political prisoners, the rural takeovers of the great estates in the Alentejo, the nationalization of the banks and industries, the expulsion and the exile and imprisonment of perceived enemies, the urban takeovers over of apartments, the mass gatherings on the streets, the emergence of the communist party from years of clandestinity, the rapid end of Europe’s last empire and the collapse of the state’s authority and deference.

There also was the return of political exiles; the emergence of new political parties, the ideological conflict between communists and socialists, and the rise of a variety of noisy and mobilized new far-left populist movements.

But the fundamental question on 25 April 1974 involved the colonial wars in Africa.

In April 1974 one in four men in Portugal were in the armed forces. A proposition per thousand of the population (30.83) only exceed by Israel (40.09) and North and South Vietnam (31.66) (55.36); five times that of the UK and three times that of the United States or Spain. By 1974 over a million had seen service in the overseas Portuguese colonies.

In Africa the Portuguese army had deployed almost 150,000 men. Many Portuguese had escaped. By 1974 some 1.5 million Portuguese were resident abroad: At least 700,000 in France and 115,000 in West Germany.

I well remember the pressure this involved myself during the tail-end of another empire. Four of my cousins had been drafted into the British “national service” in the late 1940s and 1950s: All served overseas: one in Libya, one in Hong Kong, and one in Malaya. I only missed this obligatory military service myself by one year.

Since 1964. Lisbon had been full of troops on their way to Portuguese Guinea, to Mozambique, and to Angola. Portugal was after all clinging on to Europe’s last overseas empire.

Africa was at the center of the young officers disenchantment with the regime. Ending the wars in Guinea, in Mozambique and in Angola, was their top priority, and was at the centre of their growing disenchantment with General Spinola who became the provisional president of Portugal after the coup and which led to his ouster in September 1974 and his flight from Portugal to Spain in early March of 1975.

But it should not be forgotten that it was General Spinola who invited the Portuguese communists into his government. It is a mistake, however, in my view to see what happened in Portugal as a “transition.”

What took place in Portugal in 1974 was a rupture, and especially the events over the “hot summer” of 1975 which was the key year. I will not rehearse the chronology of the revolution as this is well established, but I want to concentrate on the hot summer of 1975 and the international forces that were at play during those critical months.

First, there is the question of Brazil and its role.

On 1st of June 1975 Captain Heitor de Aquino Ferreira, reported to General Geisel on General Spínola’s visit to Brasília. Captain Heitor was the private secretary to the Brazilian president. Spínola had visited general Castro, the second in command of SNI, the Brazilian intelligence agency. He had arrived in Brasilia without his famous monocle and wearing dark glasses. I am grateful to Elio Gaspari for sharing these documents with me.

A note from General Newton Cruz to Heitor of 06-08-75. (…relates to a meeting on the 75-07-23.)

Secret

National service of informations, Central Agency (in Castro’s Hand)

Information no 1272/60/AC/75

Subject – aid to general Spinola for a reaction in Portugal

(…) 4. The carry out of investigation as to the statements of General Spinola to find out if they are true, with respect to possible assistance on the part of other countries, particularly:

- a) on the part of West Germany

— the German government is very concerned with the evolution of events in Portugal and has decided to prevent that the said country is transformed into a communist dictatorship

[notation by Geisel on “it has decided” and marks a ?)

– it is inclined, as long as it is not ostensively accused, an element capable of carrying out the reaction in Portugal

– admits that this aid could be carried out in a clandestine manner by NATO

– it is not convinced that Spinola is a man capable of leading this reaction

– it is given to understand that is a decision is made by Brazil to secretly aid Spinola it could be that a German representative could coordinate the aid.

[Geisel marks ‘?” ..in the paragraph]

(…)

- New facts

- On the 5 of august of 75 the linkage of the BND informs that the German government will send under a false name, a credentialed representative to enter into contact with SNI and General Spinola with whom it will converse about the possibility of German assistance. This representative will arrive in Brazil on the 10th of august, with the intention of meeting with an credentialed Brazilian element, if the intention of the Brazilian government is to give some form of assistance to General Spinola.

(Geisel makes “!” At the second half of the paragraph)

SNI reports on the conversation with the German, 1975-08-13

A report for Newton Cruz to Heitor on 06-08-75

There had been a meeting at the headquarters SNI in Rio on the 6 August 1975.

To discuss assistance to General Spinola on the 23 July at the central agency of SNI after his visit to various European countries. Spinola said he wanted a place in Paraguay to train men and if Brazil could provide logistical support in terms of clothing. The arms would be obtained from other sources, or if the Brazilian government agreed, could be purchased in Brazil….

The logistical support would include if possible, food, The period of instruction would be brief only that needed to instruct the men in the use of the armaments.

(…)

The German government is very preoccupied with the evolution of developments in Portugal and has decided to prevent [Portugal] being transformed into a communist dictatorship

(General Geisel had marked “is decided” and adds a ?)

(…)

On the part of the United States, it was confirmed that General Spinola had contact, but more details could not be obtained from the CIA that normally does not share information that it has, and only does so in its own interests.

Under the heading new facts:

- On 5 August 1975 the link to the BND informs that the German government will

send a representative under a false name … to discuss possible German assistance to General Spinola…(b) the group of General Spinola sought out a CIA contact to solicit the provision of hand grenades, explosives, and sophisticated detonators. This material would be proved in Spain. The CIA appears to be inclined to satisfy this request, directly or via a European country, possibly Germany.

(…)

General Spinola has invited to integrate his group, two ex-agents of the DGS (ex-PIDE) that are at this moment, one in Angola and the other in Rhodesia (Sr Alas)

..but he is not well thought of as he cooperated with Rosa Coutinho in Luanda, betraying his ex-companions to the pro-communist authorities in Angola.

(…)

The Portuguese resident in Brazil, Carlos Vieira da Rocha, and the ex-chief of the DGS (ex-PIDE) F. Reys, proposes a group of 50 chosen men, who are some in Brazil, some in Spain, who would penetrate the north of Portugal and aid those groups that have reacted against the present government…They believe that with their prestige with their armed forces and with former elements of the DGS, they could organize a movement in the north, which gradually could bring together the discontented military .. forming a crusade in the north, advancing to the south, where certainly they would obtain support.

Personal -Secret

National Service of Informations

Central Agency (marked Central Agency, signed by Castro)

Information no 20/30/AC/75

Date: 13 Aug 75

Subject: contact with representative of the RFA

Distribution: Chief of the SNI

The contact made with the representative of the RFA, who came to Brazil to deal with the possible assistance to General Spinola developed in the following form:

– it was clearly stated that the principal adopted by Brazilians foreign policy of non-intervention in the internal affairs of other countries is of fundamental importance; this position assures to the Brazilian government the moral authority to repel energetically the actions of countries that seek to intervene in Brazil’s internal affairs.

– it was made clear that it was in Brazil interest that Portugal should not be transformed into a communist country…

– the German representative was very positive in his affirmation that the German government would not allow the possibility of a a communist Portugal, because of the problems this would cause in Europe, above all in NATO, and because of this, the German government was willing to cooperate, in an absolutely discrete manner, with a group of portuguese nationals who intended to destroy the process of the communisation of Portugal.

– having said this there was a grave doubts as to who would led this movement and for this reason they were soliciting an exchange of information …

– in reality all the opposition was at this moment is centered around General Spinola

– Captain Guilherme Calvao is the military representative of Spinola, with his headquarters in Salamanca, Spain, and counted on 1,200 to 1,500 men capable of action in Portugal but which need armaments.

– major Sanchez Osorio is also integrated into the scheme as political representative, but his internal prestige within Portugal is somewhat compromised because he left the country and to take refuge outside.

– Airforce general Galvao de Melo is integrated into Spinola’s scheme but he is limited because he remains in Portugal

(…)

– ..General Spinola is for the moment the person in the condition to lead this movement, though the German representative is of the opinion that only a mass movement of Portuguese based in Spain could have success; the plan of commandant Galvão nevertheless is for the initial infiltration of successive groups of 25 armed combatentes, and known groups of resistance within Portugal, for a combined operation…

– the German government is disposed to aid financially General Spinola’s group, and to make the connections with the Spanish intelligence agency and to facilitate the infiltration of in Portugal of Portuguese elements and to give arms to the men concentrated on the frontier.

(…)

Elements of General Spinola can count on groups of combatants from Rhodesia, South Africa and Brazil

(…)

In terms of assistance we recommend the following, depending of direction from above:

- Armaments for the first infiltration groups…

[It then outlines in detail the arms needed]

This material can be assembled in Rio de Janeiro in a secure location within six days and ..

– the groups could be assembled near the airports of Galeão and Viracopos [in Brazil] and fly with Iberia, LAN Chile and Aerolineas Argentinas, that do not stop in Portugal or Cuba.

(…)

Financial aid could be provided, possibly, by the ministry of foreign affairs, in the value initially at ten to fifteen thousand dollars.

(…)

But when these favorable reports reached the “higher authority” that is the desk of General Geisel, the military president of Brazil, his response was to say definitively no.

Nonetheless, Brazil would not aid General Spinola.

A year later on the 27th of December 1976, Antonio Azeredo da Silveira, Brazil’s foreign minister, reported on Spínola in Switzerland. Spinola had obtained two Brazilian passports. The Swiss authorities were perplexed. He had used different combinations of his name in each. The Swiss had asked “what were the reasons that had led the Brazilian authorities to issue two passports to the ex-president, one for a Brazilian national and the other for a foreigner? And why had the Brazilian passport for a Brazilian not included all the identification elements for a Brazilian passport for foreigners? Silveira observed in his note to General Geisel: “A fantastic operation of the Swiss.”

Second, there is the critical role of Frank Carlucci and the American Embassy in Portugal

In Portugal the American ambassador, Frank Carlucci, not knowing about the Brazilian president’s decision not to aid Spínola had come to a similar opinion.

The U.S. should not support the far-right.

The constituent assembly elections on 25th April 1975, had revealed that support for the communists was very limited. In one of the highest turnouts ever recorded in a national election, (91.7 percent), the communist party (PCP) only received 12.5 per cent of the votes nationwide. The Portuguese Socialist Party (PS) lead by Mario Soares took 37.9 percent, and the Portuguese Popular Democrats (PPD) led by Sa Carneiro took 26.4 percent of the votes.

Despite the regional divide revealed by the election returns (the PPD in the north, the PCP in the south), it was in the central regions of the country and in the urban center’s that the Socialist’s did best. Frank Carlucci said that it was the “election that turned the situation around.” The communist leader Alvaro Cunhal said that the election “did not recognise the intervention of the military in political life, or the creative predominant intervention of the masses in the revolutionary process.”

But Carlucci had a greater problem on his hands than Alvaro Cunhal. He had Henry Kissinger to deal with. Kissinger had dismissed Mario Soares as being a new Kerenski. But Carlucci argued that Soares was “the only game in town.”

And Carlucci was able to circumvent Kissinger and get his views over these critical weeks directly to President Ford. He did this via his old wrestling mate from their student days at Princeton University, Donald Rumsfeld, who was the White House chief-of-staff to President Ford. Carlucci and the American embassy in Lisbon argued that the constitute assembly elections had clearly demonstrated the resonance that such a position enjoyed among the Portuguese population when given the chance to vote.

The alternative which the communist may well have expected, especially so soon after the Americans had backed tue coup by General Pinochet in Chile in November 1973, was that the U.S. would also back a violent armed action amongst them, something of course General Spínola was planning, and which the Brazilians had refused to support.

But this was denied them. The United States steered clear of general Spínola, and the Brazilian government did likewise. It is one of those curious contingencies of history: Sometimes individuals do matter. And in the case of Portugal, General Ernesto Geisel and Ambassador Frank Carlucci, mattered. General Spínola was not to become the Portuguese General Pinochet.

But in Africa it was different story.

Decolonization had proceeded at pace despite Spínola’s efforts to slow the process down. The MFA had made deals with the liberation movements long before the formal negotiation were completed. And in Angola the MPLA has received decisive support from the Cubans who had arrived without the Americans noticing until satellite imagery revealed a baseball field close to Luanda. Neither the Portuguese nor the Angolans payed baseball, but the Cubans did.

And Cuban troops which had clandestinely arrived in Angola while the Americans were preoccupied with Portugal, thwarted, and then defeated, the major invasion from the south by the South Africans. Roger Morris, an aide to Kissinger, said: “I think Kissinger saw [Angola} as the place to find out if you could still have covert operations.” In fact It was Fidel Casto who had sent 14,000 to 17,000 Cuban troops secretly to Angola to support the MPLA. Their intervention was critical to the defense of the MPLA and of Luanda.

Fidel Castro had hosted in Havana Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, the Mozambique born mastermind and commander of the military coup of April 25th 1974, and now the military commander of COPCON. Otelo said that he could have become “the Fidel Castro of Europe.”

But the real Fidel Castro had his eye on Africa not Europe. When Kissinger realized the need to intervene it was too late, and in any case the U.S. Congress voted overwhelmingly to prevent him. He had in any case backed the wrong horse in the conflict, despite the best efforts of Robert Moss and Bruce Loudon, both now in Angola, to support Jonas Savimbi and Holden Roberto and not Agostinho Neto, the leader of the MPLA.

Bruce Loudon was the only correspondent in Angola to “recognize” the UNITA-FLNA “government.” And Robert Moss who had bitterly criticized the lack of support for General Spinola in Salamanca, reported on 15 November 1975, “from behind the [South African] lines” in the “Spectator.”

The United States Senate, however, on 13 December 1975, by a vote of 54 to 22, imposed a complete ban on further aid to UNITA and the FNLA. The victory of the liberation movement in Angola and Mozambique inevitably brought about the end of white rule in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, and in South Africa, where it ended the apartheid regime.

In Portugal’s neighbor Spain, the dictator Generalissimo Francisco Franco died in late 1975 and the democratic transition began, not to imitate Portugal, but to avoid the rupture Portugal had experienced. Spain’s was a negotiated transition.

As a result, Spain joined NATO in 1982, and with Portugal joined the European Economic Community (EEC) in January 1986. It was a major historical shift for Portugal, out of Africa, and into an expanding European community where Portugal was to provide a successful President of the European community in the person of Durão Barroso, a former social democratic prime minister, and before that a member of the MRPP, one of most radical fringe political groupings on the far-left of the political spectrum during the wild hopeful days of the Portuguese spring of 1974.

My very first newspaper article, published in The Western Morning News on 23 August 1961, when I was barely twenty year old, was entitled “Emergent Israel: 20th Century Miracle Carved in the Heart of Islam” When I was in Israel earlier that summer of 1961, I had visited Beersheba where my great uncle, Wilfred “Bill” Maxwell, as a sergeant in the West Somerset Yeomanry (a mounted regiment), after fighting in the disastrous Gallipoli campaign, had participated alongside the Australian Light Cavalry charge on the Turkish defenses during the Battle of Beersheba on 31 October 1917.

The British and British Imperial forces from Australia and New Zealand had been attempting to outflank the Turkish position in Gaza. They succeeded in defeating the Turks and taking control of Jerusalem and Palestine. Two days after the capture of Beersheba, Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary had contacted the Baron Rothschild, and on the 9th November 1917 he announced the Balfour Declaration where he proposed a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. Portugal has of course its imperial past to contend with, but it is worth recalling that others also have this burden, and that history remains for all of us, for better or for worse, still very much alive.