Present at the Creation: Disaggregated Globalization

Dante’s “Inferno”, the 14th century epic poem, where Hell is nine concentric circles of torment located within the earth.

It is the most appropriate analogy for the seriousness of the national dilemmas and the international challenges that confront us

To start at the outer circle of Dante’s hell: The threat of global disorder

It is clear that the post WW2, but more importantly, that the post-cold war global order is unravelling.

The tectonic plates are shifting.

This is occurring both in geopolitics and in global financial markets. We do not see clearly yet how the new balance of global military, economic, and political power, will be configured.

But a reconfiguration in clearly underway.

We also know that it is such moments of fundamental chance that miscalculations and accidents can happen: 1914 with the outbreak of WW1; 1929 with the Wall Street Crash and the beginning of the Great Depression; 1939 with the outbreak of WW2; 2008 with the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the global financial crisis that followed.

It is not just a question of the balance of military power.

The US is the major global power in terms of its global reach, the scale of its alliances, its military expenditures, and the size and sophistication of its armed forces.

But the US has suffered from a series of disastrous military overseas interventions.

The lessons of the Vietnam war debacle were never learnt: The Post 9/11 “war on terror” has aggravated the situation and with disastrous consequences: In Afghanistan, that once and everlasting graveyard of empires. In Iraq with continuing post-invasion chaos. In Libya lost in endless deadly squabbles between militias and chronic instability.

It has been an endless “Tar Baby” syndrome for the United States.

China and Russia have reemerged since the end of the cold war as global competitors.

Russia under Vladimir Putin with an aggressive mixture of overt and clandestine military intervention in the Ukraine and Georgia and Syria, with cyberwars and Mafiosi style extraterritorial killings of perceived enemies and overt as well as clandestine political interference.

China with its economic growth, modernization, and heavy investment in military hardware and cyber capacity, as well as it’s overseas investments in infrastructure and commercial penetration, especially in the South China Sea, as well as in Africa and in Brazil and in eastern Europe.

The economic challenges of global disorder are also again on the horizon. It is ten years since the financial crisis produced the greatest shock to capitalism since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The system survived.

But at the cost of the massive printing of money by central banks, of “quantitative easing” and bank bailouts, and of the imposition of long-term austerity policies and severe cutbacks in public services, which has eroded the welfare state within many of the advanced western democracies.

Yet those at the top of the wealth pyramid did not suffer after the financial crisis.

No bankers went to jail. The average taxpayer footed the bill. Income inequality became worse. The rise of populism and Brexit and Trump are a direct consequence.

New trade wars and protectionism, and trade conflict between the World’s two largest economies, the US and China, are only just beginning, as are renewed financial pressures on countries from Argentina to Pakistan, as well as within Europe, on Italy and potentially in the aftermath of a disorderly Brexit on the UK.

These conditions, however, are not limited to the US and to the English-speaking world.

But they have weakened the commitment of both of the US to global institutions.

For the US, this is by design under President Donald Trump.

Within the UK it is the result of domestic divisions and political conflicts over Brexit.

The US, and the English-Speaking World more generally, have been guarantors of the global order since WW2, as they have also have been the guarantor’s of the international organizations which emerged in the immediate post-war WW2 period.

But all these are now under challenge from the US, the progenitor of them in the first place: The IMF, the World Bank. and the WTO (the world trade organization) to name only the most prominent examples.

After the 1990s the European nations which had been dominated by the Soviet Union after WW2, were all after the Fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany, rapidly incorporated into the EU and into NATO.

This followed the successful incorporation into the western European democratic mainstream of post-dictatorship Portugal, Spain and Greece in the late 1970s and 1980s.

At first this expansion to the EU and of NATO went well.

But the “democratic deficit” of the perceived interference of the EU bureaucracy in Brussels in national concerns at the grass roots level, and the even more distant European parliament in Strasburg, provoked negative reactions in many EU member states.

It is not only in Britain that reaction set in.

Italy has seen the rise of a populist nationalist rightwing parties. And it is also in precisely those regions which have recently been incorporated into the EU, including the area of the old “East Germany” were rightwing nationalists has been most active, and for many of the same reasons that the depressed and abandoned post-industrialized regions of the upper mid-west in the US support Trump, and the devastated old post-industrial regions within the UK voted for Brexit.

Trump is blamed for much of this.

But the issue is much bigger than Trump.

Trump is after all a man in his early 70s. He goes back to the epoch of the Vietnam War (which is a real war he avoided unlike many young men of his generation who had no choice and did not possess doctors to vouch they had medical conditions which prevented them serving when drafted).

Trump has long been an outsider to the US establishment. He has long had questionable relationships. His long-term mentor in New York City was the notorious Roy Cohn, formally the chief consul to senator Joseph McCarthy in his anti-communist witch-hunts in Washington DC. Trump has long been a favorite subject for New York’s tabloid press, with his marriage sagas, and his chronic misbehavior towards women.

But none of this is news, and none of this is (or should) be a surprise to anyone.

But as the President of the United States Donald Trump has been the “disrupter” in chief.

The arrival of Trump is no accident.

He represents the revival of a deeply populist, anti-global, resentful, anti-intellectual, isolationist tradition in American politics. The “paranoid style” the historian Richard Hofstadter once called it. Trump’s populism has deep roots in American nationalism.

Trump did not invent the idea of “America First.”

He only revived it.

It is not that dangers to the international system have not existed since the end of WW2.

They have.

Overwhelmingly, the greatest danger has been the risk of nuclear war. This has not happened,

But nuclear proliferation has happened and into regions of great potential instability: To Korea obviously, but also previously to India and Pakistan, and potentially to Iran.

Digital Globalization has also accelerated. The rise of mega-global companies based on the exponential expansion of digitalized information technology: Facebook, Amazon, Google, WhatsApp, Twitter, Instagram.

Their impact reaches down to the ground level globally, and in the most remarkable manner information technology and the Internet has provided platforms for information sharing, but also the means for political manipulation, and via the dark web for international crime networks for narcotics trafficking and sex.

The Russians and the Chinese and the North Koreans have all discovered how effectively these platforms can be manipulated, as of course have the denizens of Cambridge Analytica. And many of these techniques have long been used by US and western intelligence Agencies. There is no-one, for instance, caught up in, or engaged in, the Syrian civil war, who is not without an iPhone.

Migration, legal and illegal, documented or undocumented, has helped revive anti-globalist nativism in Europe and in the US. As it also has in Australia, and in South America, which is also facing the massive outflow of desperate people from Venezuela into Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and into Brazil.

It is not a pretty picture and certainly not one which looks like the recent past.

The behavior of nation states and their agents, the use of chemical weapons, and the ruthless extraterritorial murder of their opponents within the tense and changing and challenging international environment is a threat to us all.

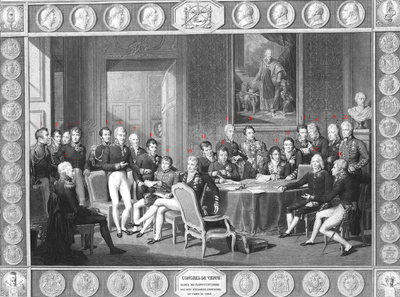

For many policy intellectuals, there are just waiting until Trump goes away and hope for the policy or intellectual equivalent to a 21st century version of the Congress of Vienna.

But that is not going to happen.

The post-post-Cold War and with it the kind of globalization of the past twenty years are over.

We need to take a hard look at the world we have and is unfolding; not the one we have lost.

Global cross learning and interactivity will remain high but disaggregation in a globally interactive context is accelerating.

The featured graphic shows the Congress of Vienna in 1815.