The Mexican Drug War and Conflict on American Territory

In April, six Republican senators introduced S. 1048 – Ending the Notorious, Aggressive, and Remorseless Criminal Organizations and Syndicates (NARCOS) Act of 2023. The bill would designate the Mexican drug cartels as foreign terrorist organizations and set the stage for military action against them.

At the same time, Republican members of the House of Representatives introduced H.R. 2633: Terrorist Organization Classification Act of 2023, and H.R. 1564: Drug Cartel Terrorist Designation Act

Also in April, the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security voted the Border Reinforcement Act of 2023 out of committee. The act would require the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to report if any of several identified Mexican drug cartels “meets the criteria for designation as a foreign terrorist organization.”

In early 2023, Representatives Dan Crenshaw and Mike Waltz introduced legislation for an Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) to target the cartels.

The legislators’ actions in 2023 tailgated actions in the previous Congress, such as H.R.2600 – Drug Cartel Terrorist Designation Act and H.R. 8030: Fentanyl is a WMD Act. (In 2019, DHS considered designating fentanyl a WMD “when certain criteria are met” but took no further action.)

In April 2023, possibly in light of increasing congressional demands for action on the southern border, U.S. President Joe Biden authorized the deployment of military reserve forces to the southern border to assist DHS with the surge of illegal migrants. The migrants are transported by the same cartels that send drugs to the U.S. so the action is minor pushback against the cartels but it probably won’t make a difference to the drug traffic.

The U.S. Attorney General responded to Congress that the Sinaloa cartel was already designated a Transnational Criminal Organization which gives the U.S. government significant authority to attack them.

Why the sudden flurry of action about the cartels?

Its partly politics as the Republicans take advantage of President Biden’s lack of enforcement action against illegal immigration in the run-up to the 2024 election. It’s also motivated by concern about the ever-rising number of drug overdose deaths, which passed the 100,000 threshold (to 106,999) in 2021. The climb in overdose deaths is largely driven by synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl, which caused a 279% jump from 2016 to 2021.

Drug addiction is widely acknowledged to be costly to society, and The Pew Charitable Trust estimates the annual cost of opioid overdose, misuse, and dependence: $35 billion in health care costs, $14.8 billion in criminal justice costs, and $92 billion in lost productivity, all after America spent over a trillion dollars fighting the War on Drugs.

And the cartels have millions of allies in the U.S. Not their members and the independent operators and gangs that move the drugs and humans, but the tens of millions of Americans who consume the narcotics the cartels provide.

According to the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, “Among people aged 12 or older in 2020, 21.4 percent (or 59.3 million people) used illicit drugs in the past year.” Those users, full-time and casual, spend nearly $150 billion annually on the stuff, according to the Rand Corporation.

Everyone agrees that synthetic opioids are a national crisis, but is sending in the Marines the best solution?

The U.S. tends to see the military as the solution to vexing political issues and the military leadership is usually all too happy to go along, but sending troops to Mexico would be an act of folly. The Americans would be starting a war along the southern border which will have consequences on the home front, unlike faraway wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria.

The U.S. and its NATO partners had two decades, near-unlimited funding, and loose rules of engagement in Afghanistan but failed to stop the opium poppy trade. One year after the allies departed, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime reported in November 2022, “Opium cultivation in Afghanistan increased by 32% over the previous year to 233,000 hectares – making the 2022 crop the third largest area under opium cultivation since monitoring began.”

Will the U.S. succeed in Mexico, a country with an economy and population much larger than Afghanistan?

Mexico has the 15th largest economy in the world, is the #2 trading partner of the U.S., and is fully-integrated in North American supply chains.

Military activity across the border would damage legitimate cross-border commerce that totaled almost $780 billion USD in 2022. According to FreightWaves, cross border trade will remain steady in 2023, bolstered by “reshoring and nearshoring of manufacturing operations to North America, particularly Mexico.”

The U.S. military was used to not getting local cooperation against insurgent forces in Iraq and Afghanistan and it’ll get that in spades south of the border. Mexicans can be expected to react the same as any other people to foreign troops in their midst, regardless of whatever piece of paper the Pentagon lawyers concoct to make the whole thing legal – at least to Americans.

Americans are pretty well armed but so are Mexicans and the cartels would quickly organize local self-defense units against the Yanqui troops. Mexicans will also be motivated by the memory of the 1916 punitive expedition against Pancho Villa (he’s the good guy in Mexico) and the Mexican Cession, the 529,000 square miles of land ceded to the U.S. after the Mexican-American War, which was primed by the American annexation of Texas in 1845.

So, will the cartels retaliate directly?

You betcha.

The cartels are well-funded, well-armed, and violent. These guys kill judges and stage mass executions (and share the video) so retaliating against the U.S. military (or American civilians) won’t be a stretch.

Retaliation wasn’t much of a concern when the U.S. was fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan as the Taliban or Islamic State weren’t likely to show up in Fayetteville for a little payback, but U.S. bases on the border like Fort Bliss and Fort Huachuca may be the first to get hit.

The cartels use armed drones to fight each other and they may repurpose them to fight the common American enemy. The Jalisco New Generation Cartel, considered the most violent cartel, used a rocket propelled grenade to bring down a Mexican military helicopter and later repeated the feat with a high-powered rifle.

And if the cartels are now called terrorists, they may link up the real thing, like the Hezbollah operators in the Argentina-Brazil-Paraguay Tri-Border Area, or whatever Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps representatives are knocking around in Venezuela.

Also, 1.6 million Americans live in Mexico according to the U.S. State Department, which is another way of saying “1.6 million potential hostages.” Will the U.S. government be as casual about their fate as it was of Americans in Afghanistan and Sudan?

Americans appear indifferent to the fact that their drug consumption is responsible for over 360,000 deaths in Mexico since the start of the Mexican Drug War in 2006. This is reflected in political leaders such as Senator Robert Menendez, who said at a recent hearing on fentanyl, “I don’t know how many more lives have to be lost for Mexico to get engaged.”

This casual rejection of suffering caused, or abetted, by America was also reflected in President Biden’s claim that Afghan military and police forces were “not willing to fight themselves’ – after over 69,095 Afghan military and police died in the 20-year campaign. (American military deaths were 2,324.)

Unfortunately, if American forces operate in Mexico there will be casualties (“collateral damage”) among the innocent Mexican population. The Pentagon will likely respond true to form and conduct an investigation, the results of which will never be made public, that will conclude “mistakes were made but no one did anything wrong,” convincing Mexicans that they, like Afghans and Iraqis are expendable in America’s pursuit of its objectives.

So, what will the cartels do?

There’s direct action against U.S. forces, businesses, and diplomatic facilities in Mexico. Attacking an embassy or consulate is a big international no-no, but if you’re now a terrorist what have you got to lose?

Then, the cartels or their surrogates could attack military bases in the U.S. or track down military members or their families for retaliation, which the U.S. government will call that terrorism, but that’s what you always call the other guy’s weapon of choice.

And, as a state of war will exist, Washington can forget any formal or informal cooperation with the Mexican government which will withdraw support from U.S. facilities and leave U.S. diplomats, military attaches, and DEA agents exposed and on their own, the Vienna Convention be damned.

Mexico may consider political-economic responses like joining BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa), the political grouping with its own development bank that has seen a flood of interested prospective members (including Mexico) in response to Washington’s demand for universal compliance with its economic war against Moscow. Or it may solicit Belt and Road investment from Beijing, and the resulting increased Chinese presence in North America will set teeth on edge up north.

Will the U.S. military be ready to prosecute the Mexican targets? Maybe, maybe not.

During the Trump administration, then-Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, General Robert Neller, even declared the Marines faced “rapidly accelerating risks” from, among other things, Southwest border operations. And after the loss in Afghanistan, the Pentagon is focused on a high-technology, peer-to-peer fight, not another squalid struggle against angry farmers. The U.S. military, which has likely spent more time thinking about defending Germany’s borders than America’s, may be unique in that it considers securing the borders a distraction from its day job.

Military leaders may also be concerned about corruption of the ranks – plata o plomo – and that’s understandable after the Fat Leonard scandal, and the corruption of military personnel in Iraq and Afghanistan. And the drug war “pros,” the Drug Enforcement Administration and U.S. Customs and Border Protection aren’t immune to bribes, so the Pentagon may be trying to avoid even more trouble in a stressed organization trying to recover from two unsuccessful campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan.

And, given the NATO-Russia war in Ukraine and rising tensions with China, the Pentagon will likely claim another punitive expedition south of the Rio Grande will make it less ready for its preferred contingencies elsewhere, though American taxpayers are justified asking why are we spending over $800 billion on the Pentagon if it can’t be bothered to defend the border.

America’s appetite for narcotics and its failure to secure the border are acts of self-harm that are seen as the acts of a sick, corrupt society by the rest of the world. They are failures that Chinese leader Xi Jinping can highlight as the inevitable end-state of the U.S. political model and “rules-based order” so beloved by U.S. officialdom and its pilot fish in the media, academia, and NGOS.

The Communist Party of China propagandists won’t even have to make anything up; they’ll just roll the tape.

What could the Americans do?

Just stop buying the damn stuff!

Nancy Reagan was mocked when she said, “Just say no,” but demand reduction will crimp the cartels’ operations more effectively than the 82nd Airborne Division. But the first step in that process will be an uncomfortable conversation about what in American society makes so many people want to self-anesthetize.

But given that America is all about options, not consequences, Washington will probably default to securitizing a social problem that is better attacked by police, prosecutors, physicians, and intelligence agencies than the army and navy.

James Durso (@james_durso) is a regular commentator on foreign policy and national security matters. Mr. Durso served in the U.S. Navy for 20 years and has worked in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq.

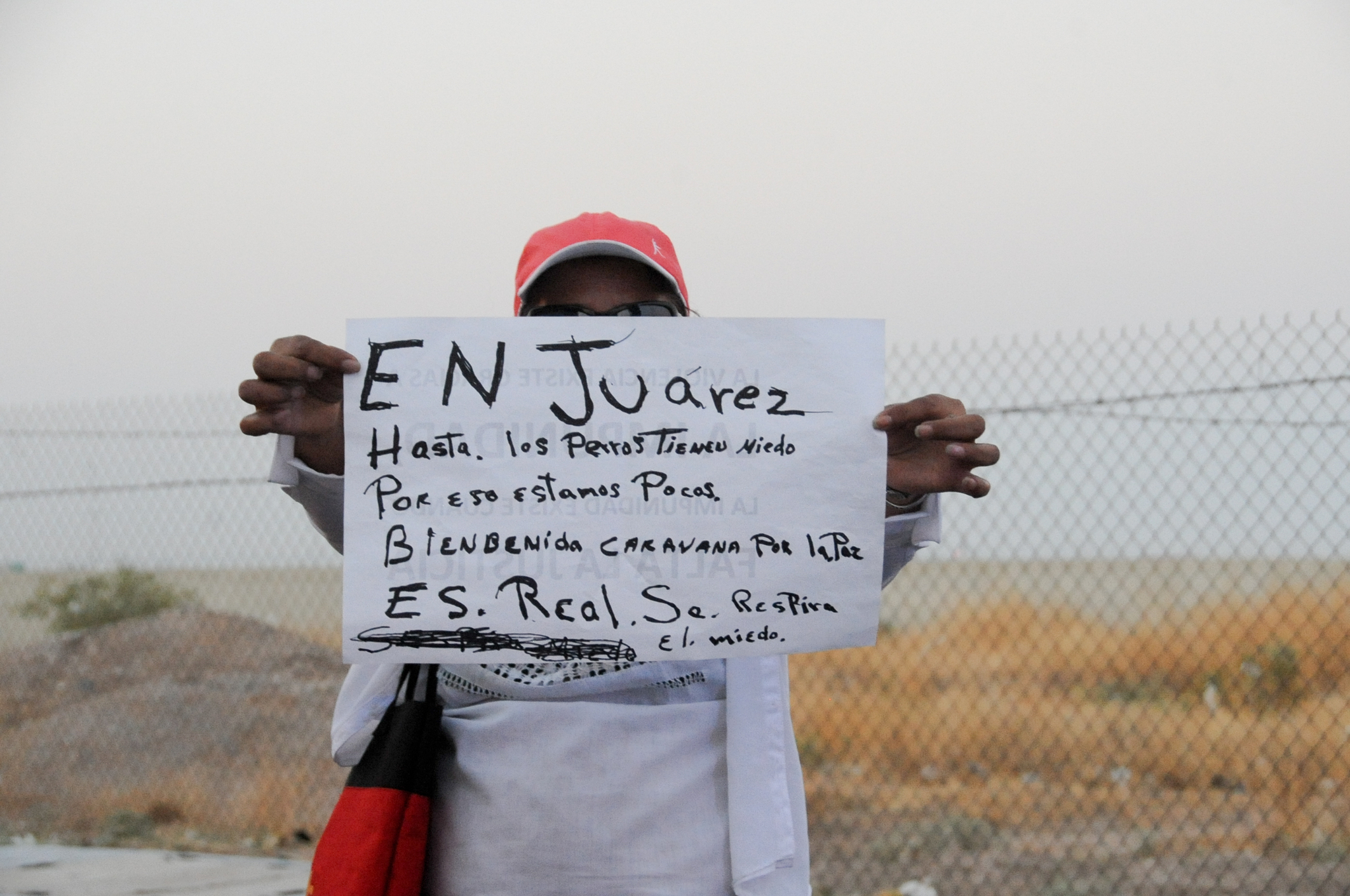

Featured Photo: Series of protests against violence produced by drug war, headed by poet and activist Javier Sicilia in Juarez Mexico. A person holds a paper saying In juarez even dogs are in fear