Brazil at the Crossroads

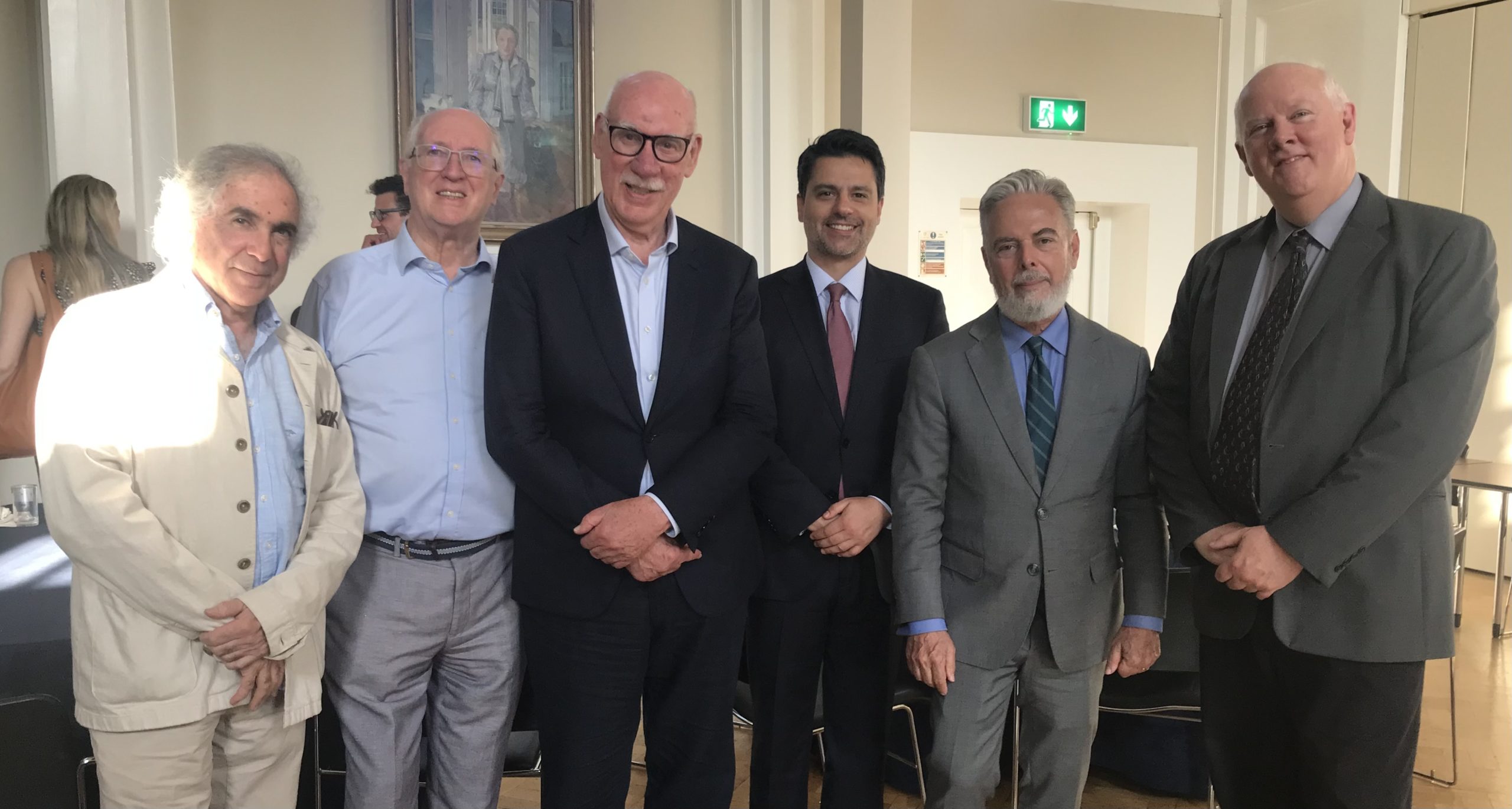

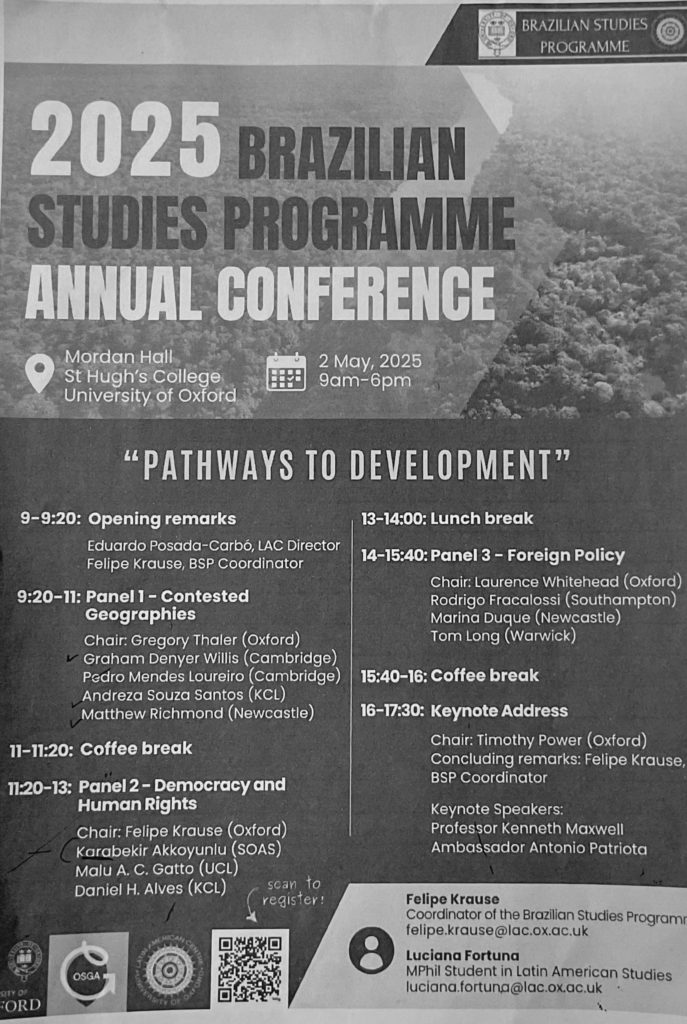

Recently, our colleague Kenneth Maxwell gave the keynote address to the 2025 Brazilian Studies Program Annual Conference held at Oxford on May 2, 2025.

In that address, he focused on Brazil facing the new “global disorder” and how President Lula will shape their way ahead.

This address constitutes the first piece of a series where we will discuss this issue, as a case study of key countries navigating a way ahead in the multi-polar authoritarian world and the Trumpian path to navigating a way ahead.

Brazil at the Crossroads

2 May 2025

Mordan Hall

St. Hugh’s College

University of Oxford

Wednesday this week marked Trump’s first 100 days in office.

We should not underestimate the challenges we face: Global disorder has been apparent for some time.

There has been the upending of the paradigms and the institutions which have dominated since the end of the Second World War in 1945: the UN founded in 1945/The World Bank in 1945/The IMF in 1945/NATO in 1949/and of American leadership, or at least of American dominance of the west or of the so-called “free world”.

This combined with the ending of the post-Soviet epoch which began with the fall of the Berlin Wall in In early November 1989/and the expansion of the EU and of NATO into the former Soviet dominated nations of Eastern and Central Europe

.The post WW2 epoch also saw the war in Korea, the war in Vietnam, and let us not forget, that post the 9/11 Islamist terrorist attacks on New York and Washington DC, Article 5 of NATO was evoked, and the American-led war on terror began, and NATO expanded operations into Afghanistan and into Libya.

Neither intervention it is fair to say were long term successful military or political engagements. Much less was American and British intervention in Iraq under Bush Junior and Tony Blair.

All this is now gone, or at least, it has crystallized in the first 100 days of the return of Donald J. Trump to White House for a second incarnation as the president of the United States.

Or as some Americans like to put it (thinking no doubt of 1950s westerns): it is the return of the sheriff in town. We are facing the continuing war in Ukraine, the continuing war on Gaza, and potential conflict between India and Pakistan, and the continuing threat to Taiwan.

This week on Tuesday we saw the first major challenge to Trump’s expansionist wish list. The overwhelming election of Mark Carney in Canada which Trump has repeatedly said he wants to incorporate into the US as the 51st State. Not to mention Greenland and the Panama Canal.

Mark Carney took the Canadian Liberal Party from near extinction to victory thanks to Trump’s bluster and Tariffs. Carney will be a formidable opponent. Formerly of Goldman Sachs/former head of the Bank of Canada during the 2008 financial crisis/ former head of the Bank of England during Brexit.

But Wednesday also saw some of the consequences of the first 100 days of the Trump administration. The markets tell a gloomy story: The Dow Jones Industrials were down 6.8%; The S&P 500 down 7.3%; The tech-heavy NASDAG Composite down 11%; the Russell 200 gauge of smaller stocks was down 13.2%. This was the worst first 100 days period to start a presidency on record.

Yet we have over a thousand days yet to go. I do not anticipate a Trump tamed. He is an old man on a mission. He believes that God saved him from an assassin’s bullet. It is a mistake to underestimate Trump.

His populist appeal and language and deep hostility and resentment against intellectuals and universities has deep roots in American political and social history. Richard Hofstadter called it “the paranoid style” of American politics. Harvard is standing up to Trump. But it will be a bitter fight. The courts are stirring. The Congress has the power to act. But in the face of an imperial minded Trump a constitutional crisis is not hard to imagine.

So how do we deal with this Trumpian new world, globally, in the Americas, and in particular in Brazil?

We are clearly having new protagonists: China/Russia/in the Middle East, in particular Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states/and the BRICS plus /Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa and the new members (Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates).

Brazil is in 2025 the current chair of the BRICS which will met in Rio de Janeiro on the 6-7 July. Dilma Rouseff, the former (and impeached) President of Brazil is the chair of the BRICS’s Development Bank which is based in Shanghai.

Brazil will also chair the COP 30 meeting (the UN Climate Change Conference) in Belem, Para, between the 10 and 21 of November this year.

Lula will also attend the Victory Day 80th Anniversary of the Soviet Victory in the “great patriotic war” over Nazi Germany in Red Square in Moscow on May 9th. He will meet his host, President Putin, as well as President Xi of China. President Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela will also be there. The Brazilian Expeditionary Force actually fought in Italy (not on the Eastern Front during WW2.)

Neither of COP 30 nor the BRICS are Trump’s favorite organisations. Brazil and Lula will be very much in Trump’s crosshairs.

So how does Brazil fare in this new, dangerous, and volatile world?

There are I think great opportunities, as well as great obstacles.

Let me discuss a few of these.

First: Internal politics. Lula and Bolsonaro are the faces of a divided and mutually antagonistic population. Both are in some ways outsiders to the Brazilian political and social establishment. Lula the poor boy from the arid northeast, and then when in São Paulo who made it up through apprenticeship and the union movement and the worker’s party. Bolsonaro, the lower middle-class boy from São Paulo who made it up though the military, the political maelstrom of Rio de Janeiro, and an eternal apprenticeship in the grubby lower ranks of the Congress in Brasilia.

As many love Lula as those who hate him, and this can be said for Jair Bolsonaro. Lula is a speaking of a fourth term. Trump was until recently speaking of a third. Many of his MAGA supporters want him to run again. Bolsonaro is facing serious medical challenges, but he is head of a dynasty. He and his sons are great friends of “The Donald.” They have all been welcomed guests at the Trump compound Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s 126 room 62,500 sq feet (5,810m) 17 acres (7 hectares) estate in Palm Beach.

Bolsonaro’s political support in Brazil is strongest among the evangelicals and Pentecostalists, now challenging the once all dominating Catholic Church. And these also have very strong links to the US. Brazil’s neighbor, Argentina, is governed by Javier Milei, who is another close ally of Trump. He waved his chain saw in Washington gifted to Elon Musk at the meeting of CPAC (The conservative political action conference) who called it the “chainsaw for bureaucracy”) Milie had waved the chainsaw during his successful 2023 run for Argentina’s presidency.

Secondly, Brazil is a cartorial state. It has a large and self-perpetuating establishment, even though very few Brazilians will admit this. I once chaired a session at the first UK-Brazil conversa in Cambridge where the topic came up. Everyone denied that an establishment existed and operated in Brazil. Yet all of the Brazilians there were members of it. None of them seemed to know of Raymundo Faoro’s great book, “Os Donos do Poder’ which discussed the historical origins and the permanence and the resilience of the Brazilian establishment. The “estamento burocrático….” Faoro called it.

Who am I talking about: The lawyers and judges that are the product of Sao’s Paulo Sao Francisco Law school, first established in 1827 and the Law School of Recife, also founded in 1827. 13 presidents of the republic, 45 governors of the state of São Paulo, studied at the São Paulo law school. The products of Itamaraty, the Brazilian foreign service, which has it origins at the time of the transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil in 1808, and when in 1823 after the declaration of Brazilian independence a secretary of negócios estrangeiros was created. Doctors: the first medical schools was created in Salvador and in Rio de Janeiro in 1808. Education: The colégio Dom Pedro II founded in Rio de Janeiro in 1837.

The military: In 1792 Queen Maria I of Portugal established a royal academy of artillery, fortification and drawing in Rio de Janeiro. The transfer of the Portuguese court to Rio de Janeiro in 1808 saw the inauguration of the in 1811 of the Real Academic Militar. Notable alumni of the military academy include the Duke of Caxias, President General Castelo Branco, President General Ernesto Geisel, General Golbery de Couto e Silva, as well as President captain Jair Messias Bolsonaro.

The financial elite of São Paulo, the mega Bankers, are also here, as are the proprietors of the great Brazilian construction companies, and the titans of Brazilian agro-business, and the heads of the great state owned Petrobras, as are curiously academics. Brazil remains one of the most unequal countries in the world and the “estamento” is comparatively speaking a small minority.

Thirdly: Legacies. Brazil has always been global. The country’s very name Brazil comes from Brazil wood, sought by European cloth makers in the 16th century for its red dye. In the sixteenth to the eighteenth-century Brazilian sugar dominated world markets; cotton in the late 18th century; Gold from the early 18th century and diamonds after 1720; coffee in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; iron ore, petroleum, soya, and beef in the late twentieth and 21st centuries.

These commodities linked Brazil to Europe, the Middle East, and to Asia. And for almost four centuries to Africa via the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans and the critical importance of slave labor to Brazil’s economic commodity production. And when the emancipation of the enslaved eventually arrived in the late 1880s European and Japanese immigrants were imported in large numbers, profoundly altering the ethnic composition of the Brazilian population, especially in Sao Paulo and the south of Brazil.

Fourth: The “interiorization” of Brazil which profoundly molded Brazil’s role within South America. It is important to remember that the interior frontiers of Brazil were established in the mid-eighteenth century, a hundred years before the US incorporated the west and California, much of it seized from what had been territory claimed by Spain and later by Mexico or the territory of the Amerindians.

The Brazilian boarder lands to the south towards the Rio de la Plata, and to the north of the Amazon River, and in the far west, were all incorporated into Brazil as a result of policy which after 1750s developed the riverine routs via the Amazon, and Madeira and Guaporé rivers to Goiás, and the fortification of these new frontiers with military forts, local militias, and subsidized trading..

The victims of these new frontiers were the Jesuits, whose missions were located in these frontier regions to the southwest and in the Amazon basin. And the Jesuits were expelled from Brazil and the order was later suppressed by the Pope. This was a world historical event which the late Pope Francis, a Argentinian Jesuit, never forgot.

But these continuities also favored Brazil since it helped guarantee that Brazil retained its territorial integrity as an independent state when it declared its independence from Portugal, a Brazilian empire under the son and then the grandson, Pedro I and Pedro II, of the Portuguese king, with its territory intact.

Aided by the intervention of a Brazilian fleet from the sea under the command of the brilliant and impecunious “Seawolf” as the French called him, the Scottish Lord Thomas Cochrane, 10th earl of Dundonald, who guaranteed that the Portuguese were defeated in Bahia and Maranhão.

Lord Cochrane was rewarded by Dom Pedro with the title Marques do Maranhão, though it took him years to receive his payments for his services. He had been expelled from the Royal Navy due to his alleged involvement in a stock market scandal which is why he was mercenary commander of the navies of Chile and then of Brazil in their fight for independence. Queen Victoria later reinstated him in the Order of the Bath and as a Royal Navy Admiral.

Fifth: The Brazil of contestation. Externally the challenge came from the French, the Dutch in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, from the Spanish perpetually during the colonial period, and from the British in the nineteenth century who preferred an informal to a formal empire.

But internally contestation came from the unruly hinterland. The great settlement of escaped African slaves in Palmares in Pernambuco which developed in 1605 until its suppression in 1694 (in what is today Alagoas); Maria Bonita and Lampião, Eric Hobsbawm’s “ Primate rebels” in the backlands of Bahia (now close to Sergipe). Canudos, the site of Antonio Conselheiro’s Messianic movement and of Euclides da Cunha’s great account in “Os Sertões”, and of its brutal suppression by the Brazilian Army aided and abetted by the local coronéis…whose assumed titles of coronel came from Pombal’s reforms of the local militias placing them under the command of local bigwigs over a hundred years before during the 1760’s.

And the history of failed revolts by local military, lawyers, Brazilian government officials, indebted tax raisers, land owners in Minas Gerais between 1788/1789, to the tailors revolt in Bahia in 1798, to the Male revolt, to Republican movements in Pernambuco, to Giuseppe Garibaldi and his Brazilian wife, Anita, in the republic of Rio Grande do sul and in Uruguay where he lived for twelve years and learned to to fight, before returning to Italy to lead the fight for unification, and in São Paulo in opposition ot the Vargas.

This is other world of Brazil: the world of of candomblé, of capoeira, of Afro-Brazilian religious practice, of music, and of carnaval. It is a rich counter-world of contestation:

Sixth; the shadowy clandestine criminal networks, domestic and international in scope. Clandestine networks/power of criminal networks/inter american and international/fuelled by cocaine and criminals/which link Brazil to the county-line drug dealers in Devon/which link the favelas in Rio de Janeiro to the rich kids in zona sul and Ipanema, and Higienópolis to Cracolândia in the city of São Paulo, and the ports of northeastern Brazil to Amsterdam and Europe where organized crime gangs now dominate the port of Rotterdam, one of Europe’s largest container and bulk ports, and Schipol Airport, one of Europe’s largest hubs and where the corruption of officials is endemic. And this is not to mention the impact of corruption in Brazil on politicians and at all levels.

But about this our chair, professor Tom Power, knows much more than I do, and ambassador Patriota can speak to the upcoming summits of COP 30 in Belem, and the BRICS in Rio de Janeiro, and of Brazil’s role in navigating this dangerous Trumpian new world.

(Note: Maxwell will continue the discussion of the way ahead for Brazil in the new world disorder in his next piece in the series.)

Featured photo: The Brazil Conference at Oxford University, Friday 2 May 2025 (Left to Right) Professor Eduardo Posada-Carbó, Dr. Laurence Whitehead, Professor Kenneth Maxwell, Dr Felipe Krauze, Ambassador António Patriota, and Professor Timothy Power.