The Industry-Government Eco System and Shaping and Delivering ADF Fifth-Generation Manoeuvre Capabilities

The title of the Williams Foundation Seminar held on October 24, 2019 was “the requirements for fifth generation manoeuvre.”

But the presentations which dealt with the defense industry and the government-industry relationship highlighted that the legacy approach which focuses on setting platform requirements will not deliver effectively fifth-generation manoeuvre capabilities.

The industrial-government eco system is evolving and that evolution needs to deliver cross-domain integration and that, in turn, requires government and industry to work together more effectively.

Getting past a narrowly focused stove-piped platform acquisition process, on the one hand, and finding ways to shape Australian defense architectures which can subsume systems bought abroad within a more integrated Australian set of capabilities, on the other hand, are two of the key tasks facing the Australian defense system.

Shaping and Delivering the Integrated Force: The Perspective of Hugh Webster, Boeing Defence

In an article by Stephen Kuper of Defence Connect published earlier this year, Hugh Webster of Boeing Defence was quoted with regard to a key aspect of meeting the challenge of shaping, building out and sustaining an integrated force:

Conceptualised as a “system-of-systems” responsible for combining the data gathering, analysis and firing solutions of inter-service platforms like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, E-7A Wedgetail, P-8A Poseidon, Hobart Class and Hunter Class and the National Advanced Surface to Air Missile System (NASAMS) LAND 19 Phase 7B, AIR 6500 has become an increasingly challenging project.

The challenge laid down to industry by the RAAF and government has been taken up enthusiastically by industry keen to be at the cutting-edge of capability delivery, particularly given the opportunity to establish a paradigm-shifting integrated, multi-domain combat and battle management system capable of air and missile defence for a force as technologically advanced as the Australian Defence Force.

Boeing, one of the prime contractors tendering for the AIR 6500 program, has sought to identify the nuances and challenges of the program, while presenting solutions to benefit all parties.

Hugh Webster, chief engineer of new business at Boeing Defence Australia, told Defence Connect, “This complex Joint Integrated Air and Missile Defence (JIAMD) and Battle Management System, really is a necessity for the ADF. The system will ‘knit together’ individual capability packages SEA 5000 and LAND 19 Phase 7B to existing ‘nodes’ and ‘shooters’ like the E-7A Wedgetail and F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.”

At present, the challenges are largely defined by integrating a multi-layered system made up of individual platforms, including the short-range, ground based air and missile defence capabilities like Raytheon’s NASAMS system as part of LAND 19 Phase 7B, with the ground-based AIR 6500 program and a national Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) system, which includes platforms like the Hobart and Hunter Class vessels, Wedgetail and F-35.

“From Boeing’s perspective, the program is too large and too complex for anyone prime to successfully deliver on its own, particularly without a clearly defined technical roadmap for each of the layers within the proposed ‘system-of-systems’,” Webster said.

Recognising this, Boeing recognised that success will require a long-term operational and technical roadmap, identifying the need for a single IAMD “glue” that will be responsible for combining the individual and highly specialised capabilities provided by other prime contractors, like Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Raytheon, through the aforementioned platforms.

“We have looked at each of the contributing platforms, like Lockheed Martin’s Aegis in the Hobart and Hunter Class, the F-35, Boeing’s Wedgetail, ‘Loyal Wingman’ and Project Currawong, and the Raytheon NASAMS platform, and recognised we need to focus on working together to deliver the outcome Air Force and government are asking for,” Webster explained.

Boeing’s technical vision reinforces the need for Defence and industry to work between and among themselves, and with Australian SMEs, to deliver local solutions that can then be paired with the right mix of US technology to deliver best-for-warfighter solutions.

“This technical vision also recognises the unique role Australian SMEs play in the broader equation. World-leading companies like CEA Technologies and Daramont bring unique leading-edge technology, systems and capability solutions to the table,” Webster said.

Additionally, Boeing’s solution seeks to draw on the methodology of successful integration programs like Project Currawong and the E-7A Wedgetail Airborne Early Warning & Control (AEW&C), particularly the close working relationships between acquirers, operational users and industry. This locally driven success developing and delivering complex “systems-of-systems” programs for the ADF shows that AIR 6500 design, integration, delivery and support would also benefit from a strong Australian presence.

“Our focus isn’t on ‘shiny new toys’, it is on helping Air Force and government to tangibly identify and answer the roadmap questions, while demonstrating the success and precedence Boeing has had combining various prime contractors, platforms, operational users and Australian SMEs to meet clearly defined capability requirements,” Webster told Defence Connect.

The AIR 6500 Project presents an opportunity for Australian industry to participate in an exciting and strategically important program to build and maintain an enduring and regionally superior Australian capability, with an opportunity to enter export markets….

Webster’s presentation at the seminar provided a hard-hitting overview on how he saw the challenges to getting at the kind of outcome he identified in the Kuper article.

If I was charged with solving future force integration, my mental frame of reference would be a Defence-industry jointly developed roadmap, which would outline the what, how and who of this next-generation integrated force. Each part of the roadmap also gives us a frame to think about what’s stopping us from great operational outcomes at scale.

The roadmap starts with the vision, which is what we want this next-gen integrated force to do in the long run to support our manoeuvre needs.

Webster then identified four operational needs which provide the pillars for crafting, shaping and sustaining an evolving integrated force.

The first level is ISR.

This starts with joint, shared, collaborative sensor networking. An easy example is the use of an air EW sensor such as the Growler in the land EW fight. When you start doing that, then you need to figure out how to manage networked sensors.

But force level ISR is more than that. Defence needs to move away from ISR stovepipes, for example find a way to fuse COMINT, MASINT and HUMINT so that we’re maximising the effectiveness of the ISR platforms and techniques that we have.

The second level is multi-dimensional C2.

We need C2 systems, doctrine and supporting training that really enables the best decisions in complex battle spaces. We will use multi-domain ISR to provide fused, all source information but the battle outcome is delivered in terms of joint integrated effects, and this takes humans to understand a situation and make reasoned decisions.

Most of you are familiar with the doctrine of ‘centralised command, decentralised control’, but I wonder if that is actually applicable in the next-gen environment anymore. A colleague of mine Antony Martin introduced a phrase that I prefer: ‘Hierarchical Command – Agile Control’.

When you think about hierarchical command, this is different than centralised command. And Agile Control is clearly not the same as decentralised control.

The third level is integrated effects.

Regardless of what you think of the terms ‘kill web’, ‘combat cloud’ and ‘mosaic warfare’, integrated effects are going to be the assymetric tool that is going to allow the ADF to succeed.

Integrated effects will be built on a network of complex weapons systems.

They will use adaptable architectures to connect across these multiple platforms and weapons systems, but interestingly there won’t be a single glue to tie them all together, it will be a complex mesh that will evolve over time.

And from a weapons perspective, we will need engage capabilities that trade range, lethality and most importantly affordability. There will need to be a mix of capabilities to penetrate as well as deliver effects from stand-off ranges, and we will need to think harder about ‘left-of-launch’ effectors.

The US experience in NIFC-CA gives us some clues about how to deliver these integrated effects. They didn’t wait to design a perfect architecture up front before they started connecting platforms across their kill web.

And so can we: we can develop our own integrated effects incrementally by networking existing and incoming systems: we can link Wedgetail, the Army Currawong meshed network, the Air Warfare Destroyer. And not only do we have these platforms in service in Australia, we also have the industrial support base to do something about knitting them together.

The fourth level is EM Battle Management.

We need extensive spectrum awareness not only about our frequency use, our adversary’s frequency use, but also NGO and civilian needs. And the latter two aren’t well documented or technically integrated, and collateral damage estimation of non-kinetic effects is an order of magnitude harder than for kinetic effects.

And finally we need them to be integrated with elements such as pschyops and information warfare, and this is really a creative arts activity.

All this leads to the need to craft the kind of architectures necessary to build, operate and sustain the ADF as an integrated force.

I want to be clear that its essential that the ADF doesn’t wait for perfect architectures to be analysed in detail before we start implementing….

I think Defence needs to lean on industry more to help. Both large OEMs and small SMEs are a vast untapped experience base. When we start doing the work, some decisions will fall to one prime or another, whereas some decisions will require some sort of collaborative work. If Defence just focuses on above-the-line resources from industry because probity is hard, you’re missing out on key intellectual capital.

Hugh Webster highlighted the barriers which the current acquisition system puts in place blocking the kind of integration which this seminar and previous Williams Foundation seminars have highlighted as central to the future of the ADF.

If we reverted back to our generational language, its like we’re trying to acquire a 5th Gen force using, at best, a 3rd Gen acquisition process. Now there is no single silver bullet here, but I think there needs to be thought applied to matching technology development cycles with acquisition cycles.

So for example, if you’re buying industrial age tech such as radars, engines and fire trucks, then it’s ok to use fairly linear, well templated processes. But if you’re buying ‘Information Age’ tech such as software, or doing complex systems integration, then you need to use modern, best practice acquisition processes.

He underscored that linking up industry labs in Australia could provide a powerful but as yet untapped capability to drive the process of innovation for an integrated force.

I think we need some acquisition machinery reform. We need to encourage flexible and innovative procurement approaches, with reformed probity processes. We need to develop and allow novel execution and commercial strategies. There needs to be greater industry engagement during requirements phases, and by that I mean industry OEM participation at up to SAP level, and not just with MSPs or ‘above the line’ contractors. We need to be looking more at the asynchronous development of capabilities: we need to prototype, then experiment, then field, and then use, rinse and repeat.

We need to do more force level integration in labs prior to operations in the field. Several companies have labs here in Australia such as NG’s SIL, Boeing’s Joint Battle Management Development Environment, Raytheon’s CAVE environment or Lockheed’s Endeavour Labs.

We need to connect these labs and do some risk-retiring integration work first, such as how might a Wedgetail operate with a JSF more effectively.

To be fair, industry will need to work hard to resolve Intellectual Property issues. Defence and Industry have to solve Inter-Industry collaboration, so that instead of Company A vs Company B, we have Company A + Company B + CoA to drive a best for warfighter outcome for the ADF.

He then highlighted the importance of a significant reshape of the training piece to force structure development.

I think there’s a disconnect between how we organise and plan for “raise-train- sustain” back at home bases, and then how we “fight” as part of a task group. If we’re serious about Multi-domain planning & tasking, should we organise differently?

He then underscored the importance of the nature of the workforce which can generate and support the way ahead for force integration.

All of our training processes need to “teach” – if I can use that word – a greater, broader appreciation of options, and how to apply creative thinking to military processes.

He concluded by tying together the various key elements to building, operating and evolving an integrated force as follows:

NextGen integrated operations requires a different approach not only to warfighting but also to acquisition, operations and training as well. We need to balance ‘information age’ and ‘industrial age’ capabilities, and recognise that NextGen manoeuvre is not just about platforms, but rather the entire ecosystem from acquisition through to operations. An Integrated Force Level approach is required for all of these things.

Now these concepts are not new. Jericho established some of these vectors, but what really needs to change is how we prosecute them. We need laser like clarity on what’s stopping us, and these fundamental blockers need to be unstuck. With our architectures, we need to make key decisions and develop roadmaps, but don’t wait for perfection. And we must unstick our acquisition processes, or we’ll be forever talking about ‘7 minute abs’ or ‘5th generation’, and not actually benefiting from these things. It will be expensive and pathfinding, but operationally we can’t afford not to.

The Challenge of Future Proofing the Force: The Perspective of Air Vice Marshal (Retired) Chris Deeble, Northrop Grumman Australia

Chris Deeble’s presentation followed nicely from that of Hugh Webster’s. And his presentation straddled both his experience in the RAAF with several cutting edge programs, and his transition to industry.

The core target which needs to be achieved in order to enable, empower and further develop the fifth generation force was identified by Deeble as follows: “Getting the right piece of information to the right shooter, the right effector, the right sensor, at the right point in time.”

He argued that such an outcome cannot occur by happenstance but must be the focus of attention from the outset.

“It must be architected.”

He argued that to “future proof” the force it was crucial for industry and government to work together in shaping an ongoing process of conceptual force development and operational innovations which entered the force and then could be fed back into an ongoing conceptual redesign effort.

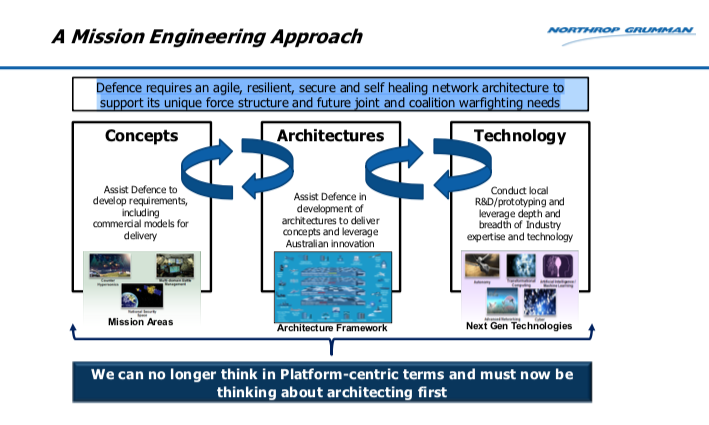

He argued that “defence requires an agile, resilient, secure and self-healing network architecture to support its unique force structure and future joint and coalition warfighting needs.”

And this required what he called a mission engineering approach which he conceptualized as seen in the graphic below:

This approach launches a conceptual, development, experimentation, training, operational deployment cycle which is critical to the ongoing modernization of an integrated force.

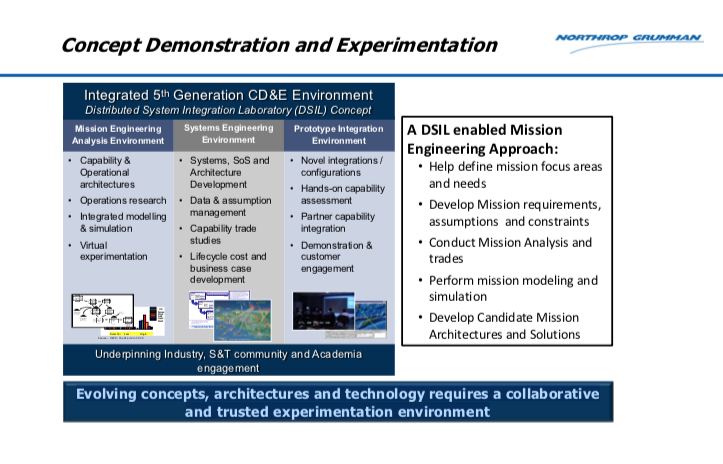

Deeble underscored the clear need for “evolving concepts, architectures and technology requiring a collaborative and trusted experimentation environment.”

In short, both Webster and Deeble underscored the need to leverage the current ADF joint force development efforts to transition to a new cycle of innovation in which industrial and government collaboration could be strengthened to drive integration by design rather than focusing on after-market integration of individually acquired platforms.

Building in Integration: Reshaping Training and Encompassing Development

The presentations of Webster and Deeble considered together underscored the importance of shaping a conceptual to development to training to operational cycle which needs to underly the “post-requirements” revolution which acquisition processes are going through.

The Australian Defence Force has set a tough bar for itself – shaping an integrated force and crafting an ability to design such a force.

This is a tough bar but one which they are trying to energize in part by leveraging their new platforms to shape a way ahead beyond the classic after-market integration strategy.

But how best to do this with regard to training and development of the force?

And how to maximize the combat effectiveness to be achieved rather than simply connecting platforms without a significant combat effect?

When we visited Fallon this year, we were impressed that the training command is adding new buildings which are designed to shape greater capability to get the various platform training efforts much better connected.

Fallon is known as the Carrier in the Desert; but as the carrier and its role within the fleet evolve and encompass distributed lethality and the kill web, so must the Carrier in the Desert evolve.

It starts with the addition of two new buildings, which embrace the shift.

One building is to house the integrated air enabled force; the second houses the simulators that drive the process of their integration.

The first building, building P420, will house the integrated training effort.

“The entire building is a SCIF (Sensitized Compartmented Information Facility) at 55,000 square feet.

“We will have offices in there.

‘We will have auditoriums.

‘We will have classrooms.

‘We will have mission-planning rooms.

‘And the building will also house the spaces from which we monitor and control missions on the Fallon Range.

“We will be able to do all of our operations at the appropriate classification level for the entire air wing.”

The additional new building will house the simulators.

“Building P440, which is 25,000 square feet, will host initially the simulator devices for the integrated training facility.

“These include F-35, E-2D, Super Hornet, Growler, and Aegis.”

We were also interested in the clear desire to shape Training, Tactics, and Procedures (TTPs) cross platforms where possible.

The F-35 coming to the carrier deck also has key radar capabilities, notably built by the same company, Northrop Grumman, and working integration will provide a key opportunity to enhance the capabilities of the CAG in supporting fleet operations.

Clearly, tools like Live Virtual Constructive training will become increasingly more important in training for the extended battlespace and there is a clear need to work integration with live assets today with US and Allied forces in order to lay down a solid foundation for something like LVC.

The team emphasized the need to have the advanced assets at NAWDC to allow for the kind of integrated training, which is clearly necessary.

They would like to see E-2Ds and F-35Cs physically at NAWDC to allow for the kind of hands on experience, which can build, integrated cross platform training essential for the development of the skill sets for dominance in the 21st century battlespace…

Hence, a different pattern is emerging whereby training is as much about combat development TTPs as it is about single platform proficiency.

“The problem is right now, we don’t have aircraft here to fully develop cross platform integration, because we don’t have enough time spent together to figure out the optimal direction to drive that kind of integration.”

But what is missing is a capability to connect training, notably cross platform training with software code rewriting of the sort, which the new software upgradeable platforms like F-35 clearly can allow.

Indeed, we added to the above article the following:

One could also add, that the need to build ground floor relationships between code writers and operators needs to include the TTP writers as well.

During my visit to Canberra, I had a chance to discuss with Air Vice-Marshal (Retired) John Blackburn how the training approach could be expanded to encompass and guide development.

“We know that we need to have an integrated force, because of the complexity of the threat environment will will face in the future. The legacy approach is to buy bespoke pieces of equipment, and then use defined data links to connect them and to get as much integration as we can AFTER we have bought the separate pieces of equipment. This is after-market integration, and can take us only so far.”

“This will not give us the level of capability that we need against the complex threat environment we will face. How do we design and build in integration? This is a real challenge, for no one has done so to date?”

Laird: And the integration you are talking about is not just within the ADF but also with core allies, notably the United States forces. And we could emphasize that integration is necessary given the need to design a force that can go up an adversary’s military choke points, disrupt them, have the ability to understand the impact and continue on the attack.

This requires an ability to put force packages up against a threat, prosecute, learn and continue to put the pressure on.

Put bluntly, this is pushing SA to the point of attack, combat learning within the operation at the critical nodes of attack and defense and rapidly reorganizing to keep up the speed and lethality of attack.

To achieve such goals, clearly requires force package integration and strategic direction across the combat force.

How best to move down this path?

Blackburn: We have to think more imaginatively when we design our force.

A key way to do this is to move from a headquarters set requirements process by platform, to driving development by demonstration.

How do you get the operators to drive the integration developmental piece?

The operational experience of the Wedgetail crews with F-22 pilots has highlighted ways the two platforms might evolve to deliver significantly greater joint effect. But we need to build from their reworking of TTPs to shape development requirements so to speak. We need to develop to an operational outcome; not stay in the world of slow motion requirements development platform by platform.

Laird: Our visit to Fallon highlighted the crucial need to link joint TTP development with training and hopefully beyond that to inform the joint integration piece.

How best to do that from your point of view?

Blackburn: Defence is procuring a Live/Virtual/Constructive (LVC) training capability.

But the approach is reported to be narrowly focused on training. We need to expand the aperture and include development and demonstration within the LVC world.

We could use LVC to have the engineers and operators who are building the next generation of systems in a series of laboratories, participate in real-world exercises.

Let’s bring the developmental systems along, and plug it into the real-world exercise, but without interfering with it.

With engagement by developers in a distributed laboratory model through LVC, we could be exploring and testing ideas for a project, during development. We would not have to wait until a capability has reached an ‘initial’ or ‘full operating’ capability level; we could learn a lot along the development by such an approach that involves the operators in the field.

The target event would be a major classified exercise. We could be testing integration in the real-world exercise and concurrently in the labs that are developing the next generation of “integrated” systems.

That, to my mind, is an integrated way of using LVC to help demonstrate, and develop the integrated force. We could accelerate development coming into the operational force and eliminating the classic requirements setting approach.

We need to set aside some aspects of the traditional acquisition approach in favor of an integrated development approach which would accelerate the realisation of integrated capabilities in the operational force.

A Multi-Domain Perspective Driving Force Integration: The Perspective of Richard Czumak

Richard Czumak is an Operations Analyst-5th Gen at Lockheed Martin and is based in Australia. He provided an overview of how the United States is dealing with multi-domain operations, the role of the Lockheed Martin labs in the United States in this effort, and how the linking up of the labs in the United States with labs in Australia can drive the kind of integration which the ADF is both seeking and building.

He provided a perspective on how the United States has progressively moved over time from earlier concepts of conventional force modernization to the current focus on multi-domain operations.

He cited the current Chief of Staff of the US Air Force, General Goldfein, who has highlighted the dynamics of change as follows:

He cited the current Chief of Staff of the US Air Force, General Goldfein, who has highlighted the dynamics of change as follows:

“In this information age of warfare, advantage will be achieved … [by] harnessing the vast amount of information our sensors can generate, fusing it quickly into decision-quality information, and creating effects simultaneously from all domains and all functional components anywhere in the world.”

And when re-considering the OODA loop, Czumak argued that each aspect of the OODA loop was in the process of transformation with multi-domain C2 being built into the force.

With regard to the Observe dimension:

- Leverage cross-domain cueing to detect and engage enemy systems

- Develop all categories of intelligence in any necessary domain in the context of opposed access.

With regard to the Orient dimension:

- Quickly turn data into decision- quality information

- Create sharable, user-defined operating pictures from a common database

- Collect, fuse, and share accurate, timely, detailed intelligence across all domain

With regard to the Decide dimension:

- Integrate actions and capabilities across domains and at lower echelons

- Rapidly plan deliberate and dynamic targeting from all domains

- Synchronize planning and execution across domains

- Enable subordinate commanders to act independently in consonance with the higher commander’s intent

With regard to the Act dimension:

- Simultaneously create effects from all domains

- Manage lethal and nonlethal fires in all domains within the same targeting and fire support coordination systems.

- Apply lethal and nonlethal fires flexibly and responsively between domains.

He cited an example of the process of change involving the HIMARS artillery system.

Earlier, when I visited MAWTS-1, the process of integrating the capability of the F-35 to leverage HIMARS into a joint firing capability was highlighted.

Then the Marines have taken that capability onboard an amphibious ship.

And Czumak cited the presence of both US Army and of a USMC HIMARS units in Talisman Sabre 2019 and there integration with the ADF as an example highlighting the way ahead.

In short, multi-domain C2 is a key attribute of the integrated force.

But to get there fully will require industry working with government in a different manner and more effectively to get around the stove-piped platform challenge.

Reconfiguring Industry to Work the Force Integration Challenge: The Perspective of MGEN Tony Fraser, Deputy Secretary Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group

Fraser provided an overview on the ongoing efforts of Defence to acquire new systems and to work the processes of integrating those systems into an process of integration for the ADF.

His overview provided a sense of the achievements and challenges facing Australia, a country which imports much of its equipment, but is expanding its work force to support that equipment but driving a process of change in which greater integration can be achieved.

His presentation provided a good reminder that mastering sustainment processes and working them more effectively in support of integrated tasks forces is a key driver of change as well.

Indeed, at the recently concluded Seapower Conference held in Sydney in early October 2019, the drivers of change associated with sustainment were highlighted by senior Australian Navy officials.

For example, in a session which focused on shaping a new sustainment approach for naval forces, Rear Admiral Wendy Malcolm, Head of Maritime Systems Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, highlighted the importance of ensuring that a new sustainment strategy be built into the build out of the next generation Australian navy.

She argued that the Australian government has committed itself to a step change in naval capability. Australia will be engaged in the most significant recapitalization of its Navy since the Second World War.

“We need to reshape the way we sustain our fleet as we go about a significant change in how we are doing Naval acquisition.”

“As a result, we need to future proof our Navy so that it is capable and lethal and available when and where they are needed.

“We need to build a sustainment model which ensures that we can do this as well.”

Sustainment has been largely thought of as the afterthought to acquisition of a new platform. She argued that with the new “continuous shipbuilding approach” being worked, sustainment needs to be built in from the start into this process approach.

“We should from the outset to consider the best ways to sustain the force and to do so with engagement with industry in the solutions from the outset.”

She noted that the acquisition budget is roughly equivalent to the sustainment budget, and this means that a new approach to sustainment needs to accompany the new acquisition approach from the outset to ensure the delivery and operations of the most lethal and capable combat fleet which Australia can provide.

“There are serious external and internal forces that are forcing change in our thinking about how we will use our fleet…. A major investment in shipyards, work force, and in new ships requires an appropriate sustainment approach to deliver the capability to do the tasks our navy is and will be required to do.”

The shift to “continuous ship building” entails a major shift in how Australia needs to think about sustainment as well. She argued that a number of technologies had emerged which allow from a more flexible and adaptative way not only to build but to sustain ships as well.

“We need to take a fleet view and to shape a continuous approach to sustainment as well.”

Rear Admiral Malcolm dubbed the new approach of a continuous sustainment approach or environment as Plan Galileo.

Similar to what the RAAF has termed Plan Jericho as suggesting that discontinuity was as important as continuity, she has argued that there is a need for significant relaunch of thinking and build out of sustainment.

Plan Galileo is built around three key efforts.

The first is an improved approach to capability life cycle management.

The second is the establishment of regional maintenance centers.

The third is associated with the first two. Industrial engagement is crucial to driving regional hubs with true sovereign capability that is complementary to the national shipbuilding effort.

She underscored the importance of shaping a sustainment capability which can provide for redundancy and to do damage battle repair in crisis situations.

And she added that the Australian navy will need to focus as well on sustainment away from Australian territory as well.

She argued that the rebuilt dockyards and work force need to become multi-mission competent rather than single platform focused.

In this regard, she highlighted the importance of building regional support centers which could support a wide variety of vessels and systems.

In other words, Rear Admiral Malcom provided a significant cautionary warning – if a shift in the sustainment model does not occur, the capability of even a newly built navy will be undercut in the conflictual world into which we have entered.

She made a vigorous case that the “continuous shipbuilding” approach needed to have a sustainment approach built in as well.

Indeed, given the dynamics of change associated within each class of ships associated with dynamics such as software upgradeability and in terms of building an integrated force within which the Navy will operate, the cross-domain operational requirements will require a modernization approach that becomes part of what one might consider to be sustainability.

And with the return of the significance of national and regional geography, the last thirty years reliance on a globalization process in which 21st century authoritarian powers have been key participants needs to be rethought, modified and reconfigured.

The presentation by Rear Admiral Malcom on the way ahead with sustainment is suggestive of how the government is addressing the need for change.

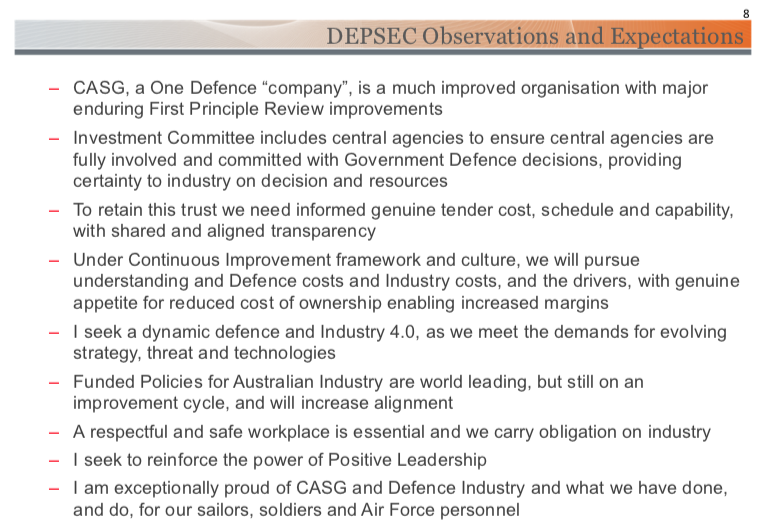

And in his briefing, Tony Fraser underscored a number of changes which the government has focused upon in shaping a way ahead.

The following slide from his presentation highlighted some of these key elements shaping a way ahead:

The Industry 4.0 piece is especially important given the digital cores being built into the new platforms being built and the central role for the evolving C2/ISR infrastructure for the reshaping of how those platforms work with one another.

An example of how Industry 4.0 is shaping a new capability for the ADF including the Maritime Border Force is the case of the new offshore patrol vessel.

This program is not being built on traditional platform lines, but is being worked in an Industry 4.0 appraoch.

In an interview I did with Robert Slaven, a former Australian Naval Officer and now with L3Harris Technologies, this process of change was highlighted:

It is clear that this way ahead, which is central to being able to shape, operate and command, an integrated distributed force is building on the legacy platforms we have now, but is also a prologue to any new platforms to be built in the future.

A case in point is the Australian Arafura Class Offshore Patrol Vessel, which is being built with the ability to leverage off-boarded systems as a designed in feature of its own operational capabilities.

In this sense, the coming of the OPV plays a forcing function role within the ADF as its shapes what they call a fifth-generation force.

“The OPV will have a crew of around 40 and be tasked with the normal Patrol and Constabulary tasks the Armidales currently do for the Navy and the Border Command.

“But because of the inbuilt flexibility of the C5/ISR infrastructure onboard, the OPV will become part of the much larger distributed force, with reachback and force-multiplication capabilities way beyond its reach as a single ship.

“It could operate as the mothership for a wide range of autonomous systems; and it can push that information into the wider battlespace.”

In other words, the OPV is being designed from the ground up with off-board systems and the new C5/ISR morphing infrastructure as key building blocks.

And given the modular flexibility associated with the ship and with the autonomous system payloads, the OPV could be an advance force element of an amphibious task force, provide support to a destroyer task force, be a key command element for a gray zone operation, and so on.

Because it is designed to be able to contribute to and to leverage unmanned systems from the outset, it can be task organized beyond its core mission.

From that sense, the future is now.

Conclusions

The key takeaway with regard to shaping the industry-government process to deliver a fifth generation combat force is pretty straightforward: shaping the collaborative processes and framworkrs among industry players and with government in delivering a capability outcome is a key part of what is required to get the capability needed.

Put in blunt terms, with the teaming that will deliver a platform narrowly considered, it will only be about technologies and platforms; it will not be about delivering integrated capability.

Collaborative teaming within Australia can be facilitated by the relatively small size of industry in Australia.

But the question of IP sharing is a key aspect facing the challenge of delivering the collaboration needed.

If the desired outcome is to deliver and evolved an integrated force effect, how do you build a team which can deliver such an effect as part of the organizational process, rather than being worked as an after-market integrative patch work solution?

The featured photo shows the industry/government panel held after the final presentations of the day at the Williams Foundation Seminar, October 24, 2019.

Hugh Webster’s Presentation

Requirements for 5th Gen Manoeuvre - H WEBSTER - Speech copyAir Vice Marshal (Retired) Deeble’s Presentation

Richard Czumak’s Presentation

MGEN Tony Fraser’s Presentation