Training for the Great Power Competition: Lessons Learned at NAWDC and MAWTS-1

During my visit to NAWDC in July 2020, I was able to talk with Rear Admiral Brophy and his senior officers throughout the week of my visit, to get an update with regard to how the US Navy aviation community is addressing the training environment for the high-end fight.

And given that NAWDC is hosting a number of working groups Navy-wide and joint force wide to rethink, reimagine and rework the role of the fleet, it is an epicenter for driving change.

As Rear Admiral Brophy put it: “Admiral Miller gave me the following charge when I took command: ‘Snap’, when you go there get us in a great power competition mindset. From a wholly-integrated perspective, look at what we need to do at NAWDC in order to win the next fight.’”

“And to do this he emphasized that my job was to pursue holistic training with the Navy and to work with other U.S. warfighting centers and key allies.”

To be blunt: this is not easy, and entails opening the aperture on what Naval Aviation is training to do, and how it will work more effectively with not just US Navy “owned” assets but those most relevant to operations against adversary forces operating in a contested battlespace.

What this means in blunt terms is that the US Navy is moving from its support to the land forces engaged in conflict in the Middle East as a key mission set, to returning to priority focus on blue water operations, and naval warfare, but in a 21st century focus.

It is far easier to write these words, than to understand actually what they mean.

And if one goes to MAWTS-1 which is not that far to fly to when operating as a Naval operator, which both the Marine and Naval aviators are, one sees how significant the shift to operating in the maritime domain against a high-end competitor is from both the operating and training perspective.

What is clearly crucial to understand is that training and its impacts are changing fundamentally under the impact of 21st century technologies.

Having discussed the shift with both Marine Corps and Naval officers this year and having visited both premier training centers, I would draw a number of conclusions.

First, the Navy and Marine Corps are focusing on how significantly to reset the capabilities of the current force, or the force they have today.

It is not about force design in 2030, 2040 or the world in 2050.

Second, both are looking to shape new skill sets to use that force much more effectively.

Third, both are preparing to use new platforms which will come into the force to enhance the kinds of capabilities needed for the contested battlespace.

Put a different way, they are reshaping their skill sets with the force they have and are doing so with full anticipation of new platforms and capabilities coming into the force.

Fourth, both warfighting training centers are in the process of reshaping their training tools and approaches to forge their ways ahead in the joint fight.

Fifth, officers of both warfighting centers are acutely aware of shortfalls in current force capabilities and are working ways to inform force development efforts to close gaps which they deem crucial rather than just buy new things.

This is especially true with regards to weapons acquisition and development.

By addressing the maritime engagement, it is clear that the stockpiles are too low and the inventory is to focused on high end strike assets.

It is clear that there needs to a significant shift towards building out a strike force which is empowered by a wide range of tools for lethality, both non-kinetic and kinetic.

For example, the threat of swarming drones is clearly on the horizon.

But how well do swarming drones do when confronted with relatively lower end munitions such as delivered by Viper attack helicopter, namely, its guns and its laser guided munitions?

Sixth, new methods of training are clearly required to guide ways ahead to reshape the force for the high-end fight, and this is not well captured by phrases bandied about by the training community such as live virtual constructive training.

There is no single technology for training, synthetic or not that can fill the training gaps being opened up by the high-end training community.

Seventh, a key advantage of the U.S. warfighter is initiative of the deployed warfighter, rather than the top down commander dominating the actions to be taken in the battlespace.

And a clear challenge will be to find ways to empower the distributed force able to operate in a flexible integrated manner to deliver decisive effect.

In short, significant change is underway but such change is not easily captured by the cubical commandos.

But this is a work in progress, and this work will succeed only if the repairs of the readiness shortfalls only recently put in place are maintained.

To train for and execute the capabilities of the high-end fight requires that training and exercises be well funded, and the innovation being generated by the warfighting centers drive force structure development.

In later articles based on my visits to NAWDC and MAWTS-1 as well as our discussions with Jax Navy, the Romeo community at North Island and at Mayport, various meetings at Norfolk, the Air Warfare Center at Nellis and at the Surface Warfare Training Center, we will further highlight what the shift in training is all about in terms of shaping the way ahead for evolution of the air-maritime force.

The force that is evolving is a very capable one, but the reset in its combat approaches and combat architecture are crucial to enhancing its capabilities to provide for the kids of escalation management and skills need for the world we are now in.

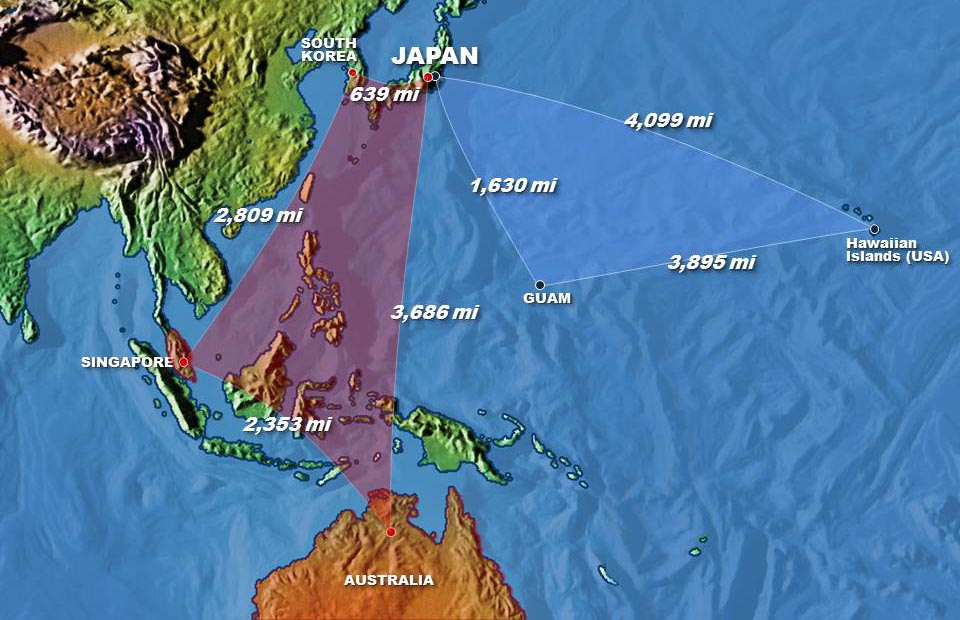

Featured Graphic: The US faces a tyranny of distance in dealing with the Pacific. And needs to operate in a strategic triangle from Hawaii, to Guam and to Japan. And in a strategic quadrangle which reaches from Japan to South Korea, to Singapore and to Australia. Credit: Graphic Second Line of Defense