The Australian Submarine Decision and Shaping a Way Ahead for the ADF

The decision to build a fleet of nuclear attack submarines is clearly a not a simple platform decision.

And its impact is not limited to the Royal Australian Navy or to the allies who are part of the agreement to shape such a force.

The ADF has been on a journey for joint force development for some time. Notably, the acquisition of the F-35 clearly drove consideration for how to shape a fifth-generation force. Now it is about a long-range fifth generation force.

It must be remembered that when the diesel submarine decision was taken, the Japanese were the presumptive favorites. At least until the decision was announced. There was much disappointment and concern in Tokyo about the shift to buying a French to be designed submarine.

Yet today, the Japanese-Australian relationship is stronger than ever in the defense domain. In part, it is so because of the same factor that reshaped Australian thinking about the submarine, namely, Chinese Communist behavior and military developments.

It also needs to be remembered that the Australians were NOT buying an off the shelf French submarine.

On the one hand, they were drawing upon the Virginia-class combat system and had contracted Lockheed Martin as the prime contractor for the new build diesel submarine.

On the other hand, the new build submarine was never the “deal of the century” as proclaimed by the French government. It was a series of contracts which could eventually lead to the build of a new design submarine. In effect, the program was shaped to work design, and then make the build decision. In effect, Naval Group had been hired as a design consultant with the expected decision to build that submarine in Australia as Naval Group and the Commonwealth resolved the manufacturing build challenges.

It also needs to be remembered how the Royal Australian Navy and the Commonwealth had shaped their new shipbuilding program. It was about taking a two-prong approach. First, there is a focus on the combat systems and integratability across the fleet. Second, there is a focus on the platform build itself. With the decision to move to a nuclear submarine, the combat system trajectory already in place for the new build diesel submarine can clearly be leveraged going forward.

When I was last in Australia, in March 2020 before the pandemic impact, I worked on a report on the first new build Australian ship, namely, the Offshore Patrol Vessel. After my discussions with the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group or CASG in Canberra, this is what I concluded about the new approach:

“Clearly the Department is focusing on a new approach in launching this ship, but a new approach which is seen to provide a template for the way ahead. It is not about simply having a one-off platform innovation process; it is about launching a new way of building this ship and in so doing setting in motion new ways to manage the initial build and the ongoing modernization process.

“It is not about having a bespoke platform; it is about shaping an approach that allows leveraging the systems onboard the new platform across the entire fleet and Australian Defence Force modernization process.

“In part, it is selecting a platform which physically can allow for the upgrade process envisaged with the new emphasis on a fleet mission systems management model. The Royal Australian Navy has clearly gone through a process of choosing a ship that has a lot of space, a lot of margins, the ability to adapt to missions by its space on deck, and under the deck for a modular or containerized solutions, extra power to operate for what comes in the future, and the ability to adapt the platform through further evolution of the design to take on different missions into the future. The platform is important; but the focus is not on what the systems specific to the ship allow it to operate organically as an end in of itself but as part of wider operational integratable force.”

What this means in blunt terms is that the platform has changed but the focus on an integratable combat system has not. The first was the focus with Naval Group; the second was always the focus with the Lockheed Martin team and will almost certainly continue.

The nuclear attack submarine choice is obviously a significant step in shaping new capabilities for the ADF and for the Commonwealth.

But before discussing this aspect, we again need to focus on the continuity aspect. That revolves around theater anti-submarine or underwater warfare. The RAAF is adding significant capability to work the Royal Australian Navy in this domain, most notably in terms of the P-8 and Triton capabilities. The Australians do not have a separate Naval Air Force as does the United State, so RAAF and RAN integration is crucial to shaping a joint force moving ahead.

What the new nuclear submarine will add is reach, range, speed and enhanced survivability, which enhances ADF capabilities over all.

The context has not changed, but the capability to be operate more effectively in that context will.

This is how I assessed that context after my March 2020 visit:

“There are three key elements of change shaping the operational context within which the Attack Class submarine will enter the force. The first is a significant evolution of theater anti-submarine warfare, with the coming of the P-8/Triton dyad, likely leading to further integration of the Royal Australian Air Force with the Royal Australian Navy.

“The second will be the rollout of maritime remotes as part of the kill web within which ASW will evolve, with sensor networks mutating and migrating through the arrival of artificial intelligence systems working networked sensors and with sensors themselves evolving to allow for direct interactivity among the sensor themselves.

“The third is migrating the skill sets and innovations generated in this decade from the continued evolution of the Collins Class submarines. During my visit to HMAS Stirling, I had a chance to discuss with submarine commander Robin Dainty.

“According to Dainty: “The demand side and the concepts of operations side of innovation affecting the naval forces will be very significant in the decade ahead. This will be a very innovative decade, one which I have characterized as building the distributed integrated force or the integrated distributed force. What this means for the submarine side of the house and for ASW is working new ways to cooperate both within national navies and across the air-naval-land enterprise of the allied forces. The decade will see new ways to link up distributed assets to deliver appropriate effects at the point of interest in a crisis. It will involve working new weapon and targeting solution sets; it will see an expansion of the multi-mission responsibilities for platforms working in the distributed force. And the Collins class will be participating in this path of innovation and lessons learned as well as technologies evolved both on the ship or the extended battlespace enabling the evolution of an integrated distributed force.”

I followed up with then Deputy Chief of the Royal Australian Navy, RADM Mark Hammond, to get his assessment about the context within which the new attack submarine was going to enter into the ADF.

“The Attack Class submarine will be a fully interoperable ADF asset optimized to survive and thrive in the contemporary and future ASW threat environment. This means deliberately designing for interoperability with our own forces, our partners and our allies. It also means integrating in the design and construction methodologies the options and margins to enable future capability enhancements.“

“In my view, our Future Force must be designed to safely and effectively operate in the ‘environment of relevance’ and fight at the ‘speed of relevance’. Neither of these reference frames are static, and both are ambiguous. But failure to consciously consider and mitigate the risks posed by either will lead to inferior capability”

It is hard to NOT see how a nuclear attack submarine meets these objectives more effectivey seen from a Royal Australian Navy perspective.

There are significant eco-system impacts of the nuclear submarine decision. Australia will build its basing structure to accommodate this class of ships, which means that they can host from time to time its allies who have such submarines, whether French, British or American. It also means a challenge for crewing as the Collins to Virginia is nearly three times increase in crew size.

It is about coming to terms with Western Australia and the need to build up infrastructure literally to support basing and to do so on the Eastern side of Australia as well. This will take time, money and a long-term commitment.

There is the question of time and the submarine gap which would occur if Australia is to build its own version of the Virginia or the Astute in country as the only option. But of course, it is not the only option.

Back in the 2015 to 2016 period, I talked with a senior U.S. Navy official and posed the possibility of working a deal with Australia to operate the Los Angeles class submarines prior to engaging in our new build projects. I do not see why that is not an option now. And with the UK-US-Australian partnership shared crewing to get the process started is clearly an option.

The impacts of this decision reach beyond the Air Force and Navy. The impact on the Australian Army is significant. The turn towards a need for Northern Territory and Western Australian defense clearly is ramped up. The need to operate effectively from the West of Australia out to the First Island Chain becomes even more significant, and the Australian Army role is clear in this regard: a more USMC-like force is required.

In short, acquiring a nuclear attack submarine is the next step in the evolution of the ADF.

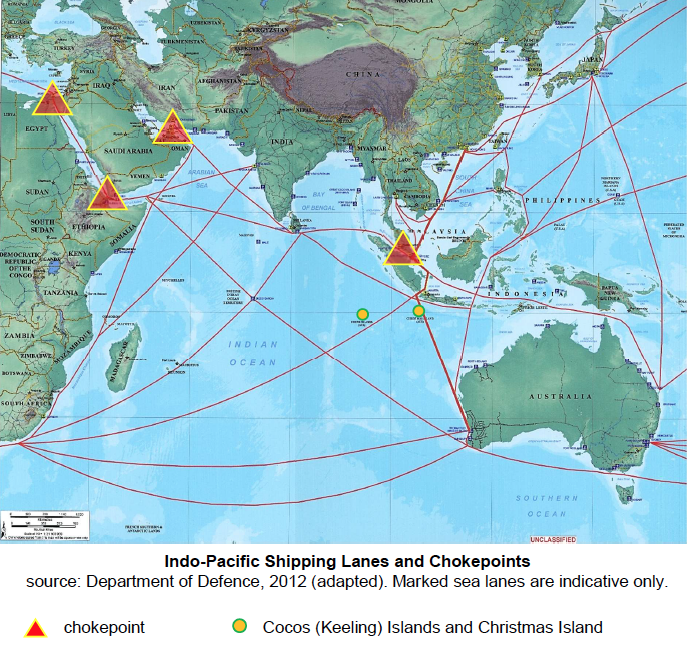

And it is one about extended the reach of the ADF in the Indo-Pacific and reinforces the strategic shift under way for Australia’s role in the region.