The Timeline for the Tiltrotor Enterprise: A Con-Ops Perspective (Part One)

Another way to look at the timeline for the development of the tiltrotor enterprise are the evolving concepts of operations and mission profiles which the users of the aircraft were able to use them for.

And as each phase of the learning curve was mastered that enabled another phase of the learning curve to be experienced.

The tiltrotor enterprise did not experience the classic challenge of mission creep: it was an enterprise that embraced the expansion of missions as new operational lessons were learned and new capabilities could be added by new techniques of adding such capabilities were developed.

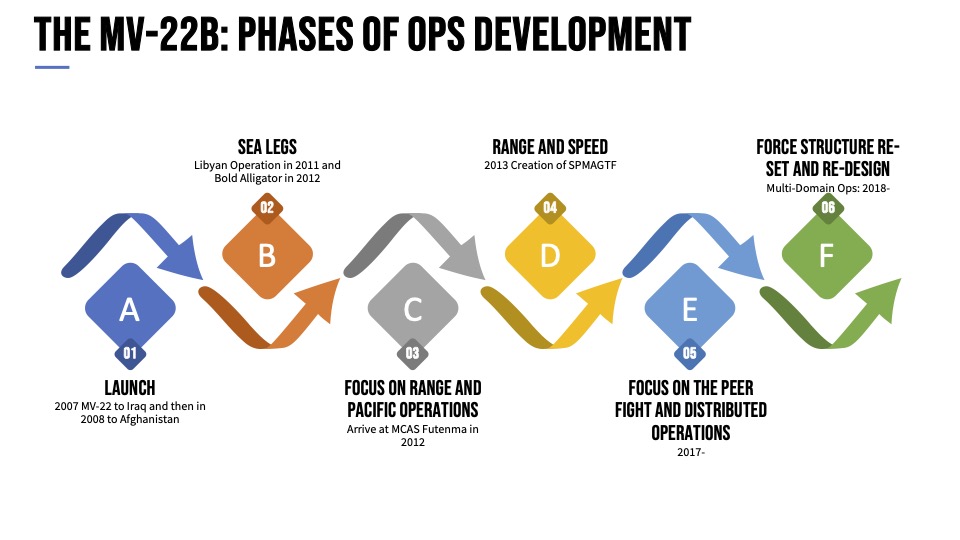

A timeline conceptualized for MV-22B operations in these terms might look like this:

I will provide a brief characterization of each phase in the conceptualization of the con-ops evolution time line in this article and follow-on articles.

Launch: 2007-2011

The Osprey was IOCd and then sent to Iraq. And then in 2009 it was sent to Afghanistan.

The Marines who took the Osprey were pioneers and the original stakeholders in what would become a tiltrotor enterprise. But they were taking a new aircraft into combat: it was a test by fire, not back in test ranges in CONUS.

And operating in Iraq and Afghanistan in terms of the terrain was very different. The aircraft was being challenged to perform in very different terrain and climatic conditions. And the Marines were part of a joint force against a reactive enemy.

The speed and range capabilities of the Osprey became evident early on in Iraq. As one Army general I interviewed who flew on the Osprey to visit his troops scattered throughout Iraq put it to me with regard to why he chose the Osprey on which to fly: “It was the only aircraft that could cover Iraq and land in the various locations I had to visit in one day.”

The ability to fly and land at speeds and angles which a rotorcraft could not do allowed the other elements of the USMC force to be used differently from the outset in Iraq. And when it went to Afghanistan, it would enable the development of new concepts of operations in using the rotorcraft as well.

As I noted in 2012 overview piece on this period:

We can start first with the decision of USMC leaders to deploy the plane to Iraq.

This deployment was itself part of the “testing” process. What is often overlooked is that testing is really done by pilots and maintainers in combat, not by technicians in white coats or statisticians at the GAO. There was clear concern expressed to me by Marine Corps Aviators that the deployment to Iraq would prove challenging, and its was. But it was also evidence of the role of leadership in making the hard decisions to role out needed capabilities and let the users define the direction of a program, not the program managers….

What we have seen is that the plane started with “training wheels on” its deployments, and those wheels not only have been thrown off, but as time in combat has gone up, the Marines as well as the Combatant Commanders have begun to understand what a transformational platform can do when connected with other capabilities and assets.

The plane started in Iraq built around a famous diagram showing the speed and range of the aircraft in covering Iraq. As one Marine commented: “The MV-22 in the Area of Operation (AO) was like turning the size of the state of Rhode Island into the size of Texas.”

It was the only “helicopter” that could completely cover Iraqi territory. And in this role, the testing of support as well as operational capabilities was somewhat limited as Marines tested out capabilities and dealt with operational challenges. The plane was largely used for passenger and cargo transport in support operations in difficult terrain and operating conditions.

It was used for assault operations from the beginning but over time, the role would expand as the support structure matured, readiness rates grew and airplane availability become increasingly robust.

From the beginning the aircraft impressed and foreshadowed later developments. As General Walsh, now Deputy Commanding General Marine Corps Combat Development Command noted in an interview at the Cherry Point Air Station in 2009 after a year in Iraq that with the withdrawal of US forces from Iraq there was a roll up of forward operating bases.

This meant that the remaining forces had to cover more ground and to provide protection at greater distance. Enter the Osprey, which did not require FOBs to provide lift and support to forward deployed forces.

Indeed, General Walsh underscored that as the U.S. forces withdraw, there was demand for more – not less – airpower.

This happened on several levels. On one level, this was due to the drawdown of the number of combat posts, which supported operations in Iraq. American forces continued to work with Iraqi forces but now had to commute from distance to do their work, rather than being in close proximity to combat posts. This meant that airpower had to provide regular support to the transit of US forces working with Iraqis.

According to Walsh: “At one point we had 140 combat posts; while we were there we went from 36 to 4 combat posts; so air was relied on more frequently for convoy protection. As we drew down combat posts and associated capabilities, air was relied on for capabilities which had earlier been largely provided by the ground forces.”

On another level, this was due to the need to protect the convoys moving equipment out of Iraq.

As Walsh underscored: “As you close down and do retrograde, you have to move further out in road miles and that requires air support.”

In addition, transport needs to move support elements to work with Iraqis increased demands for air transport.

Walsh noted: “We were increasingly asked to provide support for partnering operations.”

Iraq was the beginning and a consciousness raiser for troops and commanders.

One story told to me in 2010 by a battle-hardened Marine was as follows:

Major Lee York: “We took some soldiers out to the West of Iraq. The crew chief comes up to us and tells us that the guys won’t get out of the plane. We’re like, what are you talking about? They said we’re not there yet. And we said, “What are you talking about?”

“He then said, “The last time we did this flight it took an hour and a half. We’ve only been in the plane for 40 minutes so we can’t be there yet.”

“The last time we did this flight it took an hour and a half. We’ve only been in the plane for 40 minutes so we can’t be there yet.”

“We told him to tell the Marines that “we were cruising at 230 rather than at 120 so we were there. I swear we’re here, you know, we’re not going to send him somewhere where he is not supposed to be.”

Next on the agenda was the beginning of deployments to Afghanistan, which of course continue.

The Afghan phase of deployments has seen the aircraft and its operator’s transition to more assault combat operations over time, to the point where the latest Osprey squadron just came back from Afghanistan with record setting assault operations for the Osprey.

A metric to measure the transition can be seen in the number of named operations the Osprey squadron participated in in Afghanistan. Over time, the Osprey squadrons have significantly increased their involvement in what the military calls Named Operations, and these operations are air assault operations in support of U.S. and coalition forces. The latest squadron VMM-365 (the Blue Knights) conducted nearly 200 named operations, which was a 20-fold increase over the squadron which preceded it in Afghanistan.

In the words of the head of 2nd Marine Air Wing – Major General Glen Walters — upon his return from Afghanistan:

“The Ospreys had their normal fair share of general support, resupplies, etc. But we started accelerating their use as my time there went on, and used them for both the conventional and Special Forces operations.

“The beauty of the speed of the Osprey is that you can get the Special Operations forces where they need to be and to augment what the conventional forces were doing and thereby take pressure off of the conventional forces. And with the SAME assets, you could make multiple trips or make multiple hits, which allowed us to shape what the Taliban was trying to do.

“The Taliban has a very rudimentary but effective early warning system for counter-air. They spaced guys around their area of interest, their headquarters, etc. Then they would call in on cell or satellite phones to chat or track. It was very easy for them to track. They had names for our aircraft, like the CH-53s, which they called “Fat Cows.”

“But they did not talk much about the Osprey because they were so quick and lethal.

“And because of its speed and range, you did not have to come on the axis that would expect. You could go around, or behind them and then zip in. We also started expanding our night operations with the Osprey. We rigged up a V-22 for battlefield illumination.

“A lot of these mission sets were never designed into the V-22 but you put it into the field and configure it to do the various missions required. And we have new software for the Ospreys in Afghanistan where you can pick your approach, angle, approach speed and let the aircraft do it all. That is a huge safety gain.”

Sea Legs: 2011-2015

Without success in the first phase, there would not have bene the next one. The Marines operate from flexible and mobile bases. Sea basing is a key attribute of the Marines as the nation’s 9/11 force. But the operation of the Osprey from the sea was not the primary use of the aircraft when introduced with the priority being placed on the land wars.

But the Marines early on focused on developing their sea legs and learning how to sustain the aircraft afloat. These are different skill sets than operating from land and land base support elements.

I attended several of the Bold Alligator exercises in this period and saw and flew on Ospreys which were a key part of developing a new approach to assault at distance from the sea. I remember Bold Alligator 2012 where the journalists were waiting for the amphibious vehicle assault from the ship but the assault had already happened deep inland by an Osprey contingent.

And during the exercise an Osprey landed on an Military Sealift Command TAKE ship, demonstrating its flexibility to work within the fleet.

But the hallmark event in this period was the Libyan intervention. Here the Obama Administration decided to lead from behind which included not using a large deck aircraft carrier in the operation but sending an ARG-MEU. But this ARG-MEU was Osprey-enabled and did things no ARG-MEU had ever done before.

This became clearly evident when a USAF pilot had to bail out in enemy territory and the USAF reaction time paled in comparison to what the Marines could do with the Osprey and the Marines pulled the pilot out before he could be captured and become a political pawn in the conflict.

As my long-time colleague Ed Timperlake wrote in 2011:

A key military and diplomatic result can occur from an action, which eliminates a bad result. In the social media or internet age, a problem that can be seen is more likely to be discussed than a problem which did not happen because of a military success. More often than not, core military professionalism enhanced by the appropriate equipment actually works and problems are avoided by NOT having a failure.

In a certain sense, the phenomenon of avoiding an outcome by having a capability to create a better outcome is central to military or diplomatic success. It is important to indicate the value of a platform, system or professional capability, which shapes avoidance of a negative outcome, as well as describing in terms of what it does. What a system can avoid is in many ways as important as describing what it can do.

In some ways, this is the military variant of a null hypothesis. One can prove the validity of the military platform, system and capability by what it avoids. One test’s its value by hypothesizing alternative outcomes absent the capability.

I once had an enjoyable discussion with Ron Maxwell the Director of the great American epic movie Gettysburg. His art and vision will truly stand the test of time. I was curious about all of his many challenges. He said one of the most difficult for both a Director and the actors in such a movie was to stay in the moment as it was historically playing out.

In other words, it was important not to act as the outcome was already pre-determined. The actors playing real life battlefield commanders had to assume they were making life and death decisions for thousands of lives and the fate of America without certainty of the outcome. That was the great success of the movie since both the Director and actors truly captured the moment-to-moment uncertainty of decision making in an epic historical battle.

In real life, Commanders are constantly faced with making decisions, some routine and in fact boring others as Gettysburg shows are decisions that can have huge consequences. It is why experienced leaders, not managers, are needed at all times in the American Military. And is one of the core differences between real commanders and cubical commandos.

A leader knows what to do in the moment of action. Getting to that moment requires preparation and attention to detail while inspiring all to perform their crucial responsibilities to the best of their ability. Training tactics and technology have to all come together to accomplish the mission.

Of course, a reactive enemy and the “fog of Battle” always comes into play.

Finally, Napoleon’s quip about wanting a “lucky” General is more real then people think and good commanders can both make their luck and also catch a break with a reactive enemy making a mistake. But they do not have perfect knowledge.

When a USAF F-15E Strike Eagle crew call sign “Bolar 34” ejected over Libya in the current NATO air war against Quadafi, they were in real difficulty without a trained rescue team. And a US Navy Marine team off the Libyan coast was trained and ready to save them.

The USS Kearsage Amphibious Readiness Group with Navy Commodore Pete Pagano Amphibious Squadron Four, and Col. Mark Desens’s 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit were in the right place at the right time.

The time of the operation was significantly reduced because of the team and their use of the Osprey aircrafts onboard. The time from order to execute to the 26th MEU’s MV-22 successful extraction, called a TRAP (Tactical Recovery of Aircraft and Personnel) recovery mission was 47 minutes. Those forty-seven minutes may have changed the entire narrative of ongoing combat operations against Qaddafi.

From Gettysburg and other bloody Civil War Battles, America has shown as a nation we will accept horrendous causalities if the individual warrior and their families think the cause is just. However, there is another American core value as exemplified by the American military saying, “leave no one behind.” The TRAP mission captured that battlefield ethos.

However, what if the aircrew hadn’t been saved but rather fallen into the hands of Qaddafi’s forces? Current events would be way different. The leader of Libya maybe a lot of horrendous things but over time he knows how to play the propaganda game as a master. One American in enemy hands, if history is any guide, would have pivoted the world wide 24/7 media to a “POW Story.”

Whatever one thinks of the political decision to have a NATO Libyan Air War, it is being fought by mature adults who saved the day in the TARP mission. An Administration can be vexed and paralyzed by a POW story line. President Obama can be thankful of not having to face the null hypothesis which would have resulted from NOT having the TRAP team armed with the Osprey….

Now with the horrific weapon and the will to use it by Islamic fanatics of filming captives being beheaded, the issue of being held captive has escalated to an entirely new level of media attention. One US or Allied airman captured will certainly get attention and perhaps even change the course of events.

The USN/USMC ARG-MEU team did not let the Obama Administration have that dilemma, at least for now.

So how did the Marine Commander accomplish his mission?

He built on the dedication and vision of those who came before. Land based assets in support of the Libya operation were time, distance and tanker constrained. But the Marines had both the MV-22 and the VSTOL AV-8 Harriers on the ARG deck.

In ten minutes from the sea, Harriers could go from feet wet to feet dry. The Osprey could swoop into any terrain hover land and extract the crew. CH-53’s with a strong quick reaction combat force of Marine infantry could be called into battle at a moment’s notice. This aviation technology revolution was the key along with Marine training going back to the founding of the Corps.

The ARG was afloat in the Med while the normal USN Med Carrier Battle Group this one organized around the USS Enterprise “The Big-E” was in the Indian Ocean flying air-to-ground combat missions in support of NATO forces fighting in Afghanistan.

“The Big-E” is a Navy legend for over four decades. In peace and war ever ready for what ever the National Command Authority thinks necessary. But if one were to watch the Enterprise in action from Yankee Station off the Coast of Vietnam in the sixties to the current ops in the IO in support of Afghanistan mission there would be little difference except more modern Fighter and Attack aircraft. In fact the F/A-18 brings both missions together.

However, if one were to observe the Navy/Marine Gator team off the Coast of Vietnam in 1968 to Col. Desen’s 26th MEU it would not be recognized. The emerging ARG with the ACE (Air Combat Element) of the MV-22 and VSTOL Harrier –soon to be followed by the revolutionary Air-to-Air and Air-to-Ground VSTOL F-35B will revolutionize American combat agility from the Sea to the Sea for decades to come. Of this there can be no question.

The Amphibious Ready Group is becoming the Agile Response Group under the influence of the new technologies being deployed on the ARG ships.

As Marines are want to say to Navy CBG’s “good on em” but please pay attention to the fact that in one brief moment, 47 minutes, Marine air assets altered the course of our most current war.

The featured image: An Osprey operating in Afghanistan during its first tour of duty there. Credit: LtCol Bianca