Looking Back at the Portuguese Revolution on its 50th Anniversary

Margarida Mota, the foreign affairs reporter of Lisbon’s leading weekly newspaper “Expresso,” interviewed me for her article on the reaction in the press overseas to the “Revolution of Carnations” in Lisbon which took place on April 25th 1974.

This week marked its 50th anniversary.

Junior officers of the Portuguese army in a lightened coup d’etat had overthrown the oldest right-wing dictatorship in Europe with hardly any bloodshed. Thousands poured into the streets of Lisbon to welcome the end of the dictatorial Salazar/Caetano regime and the rebirth of Portuguese democracy.

The coup d’etat in Lisbon came as a complete surprise to the world at large, and it soon bought about the end of Portugal’s wars to retain the Portuguese colonies in Africa. In fact this was the major objective of the junior military officers who had made the coup who were tired of their endless deployments in Mozambique, Angola, and Portuguese Guinea.

I had first lived in Portugal ten year before the coup, and I had visited Portugal several time thereafter for lengthy periods of research in the archives. I knew that when General Antonio de Spinola, the former commander-in-chief of the Portuguese armed forces in what was then Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea Bissau) published his book “Portugal and the Future” in February 1974, that something serious was afoot. I was then at the institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and I persuaded Bob Silvers of the “New York Review of Books” to send me to Portugal to cover what was going on.

This article by Margarida Mota well captures the consequences and my role as one of the few early interpreters of the “revolution of carnations” in the United States. It was a important moment when the world was more used to rightwing military dictatorships, especially in Latin America (this was only a year after the bloody take over by General Pinochet in Chile), and when a military intervention brought not the prospect of more repression, but the aspiration and the hope for a democratic future.

April 25: The “Neat Revolution” as the Foreign Press Called It

By Margarida Mota

The military coup in Portugal took the world by surprise.

“In Latin America, the military was establishing right-wing, authoritarian and repressive dictatorships. But in Portugal, there was a military coup in favour of democratizing the country,” British historian Kenneth Maxwell, who explained the Portuguese revolution in The New York Review of Books told Expresso. And he recalls: “At first, it was difficult for people to understand…”

When the echoes of a military coup in Portugal rang out around the world in April 1974, it wasn’t immediately clear which political tendency it would be. Latin America had endured more than ten years of military interference in political life, which had contributed to forcibly deposing democratically elected governments and putting right-wing authoritarian regimes in power.

The most recent case was still fresh in the memory. Seven months earlier, on September 11, 1973, a bloody coup d’état in Chile, led by the head of the armed forces, Augusto Pinochet, in conjunction with the United States, had overthrown the socialist President Salvador Allende.

These were the years of the Cold War and many countries were aligning themselves with areas of influence subservient to the two superpowers – the United States and the Soviet Union. If Chile fell definitively to the North American hemisphere, quo vadis Portugal?

“At the time, in Latin America, the military were establishing right-wing, authoritarian and repressive dictatorships. But in Portugal, there was a military coup in favour of democratizing the country. It was a big surprise for everyone,” British historian Kenneth Maxwell, who has made a name for himself in the field of Latin American studies and who, in 1974, wrote about the Carnation Revolution in an American magazine, told Expresso.

“It was difficult for people abroad to understand that young military men in Portugal wanted to create a democracy, because they had a vision of the right-wing dictatorships in Latin America. I tried to explain that in the articles I wrote.”

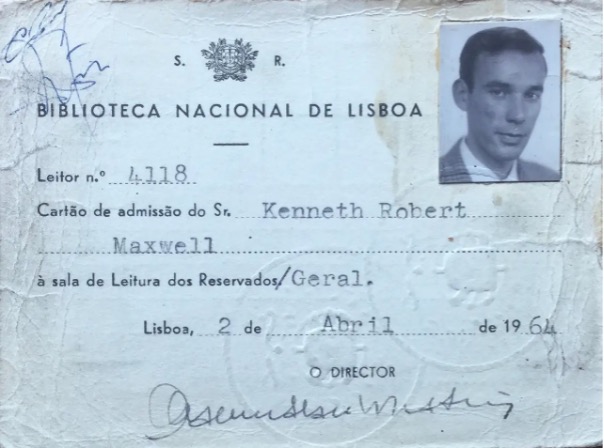

When April 25 happened, Maxwell had left Portugal three days earlier. His academic research into the relationship between Portugal and Brazil, then at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, led him to visit Portugal for several periods after 1964 to work in the Portuguese archives.

He knew the Portuguese political and social reality well and, for this reason, when General António de Spínola’s “Portugal and the Future” went on sale on February 22, 1974, he was incredulous. “How was it possible for a book like that to be published?” he asks himself. The book, which quickly became a bestseller, was an acknowledgement by a leading figure in the regime that the colonial war could never be won.

FROM UNIVERSITY TO JOURNALISM

“I got in touch with Bob Silvers, who was editor of The New York Review of Books, and told him that I thought something could happen in Portugal,” recalls Maxwell, now 83 and retired from a teaching career at Harvard University. “Bob Silvers was a good editor, he had a very good appreciation of the European situation, he had lived in France for a few years, and he accepted my proposal to go to Portugal. He gave me credentials as a journalist and sent me to Lisbon.”

Maxwell visited Portugal in the weeks before the revolution. In the article he published on April 25 in The New York Review of Books, on June 13, 1974, he wrote:

“Much of the countryside seemed to have been visited by the bubonic plague. Whole villages were dying, roads deserted and fields abandoned. I saw, on the ruined walls of closed houses, simple writings denouncing the police and the high level of prices; at many crossroads there were Republican guards with carbines and bicycles – of little use against an army, but quite efficient against old women in slow ox-carts.”

Maxwell had come to Portugal for the first time ten years before April 25. He wanted to get to know the country and learn the language. He had a small financial cushion thanks to the articles he wrote for a regional English newspaper, the Western Morning News, which paid him 5 pounds and 5 shillings per piece.

After an interview with the director of the Gulbenkian Foundation’s international service, Guilherme de Ayala Monteiro, he was still able to get support for his stay and private Portuguese lessons. “Now Lisbon is full of foreigners, but in 1964 I was one of the few foreigners in the city. It was very difficult to get in touch with Portuguese people. The PIDE were hanging around cafés and people were afraid to talk. Nobody would talk to me,” he recalls.

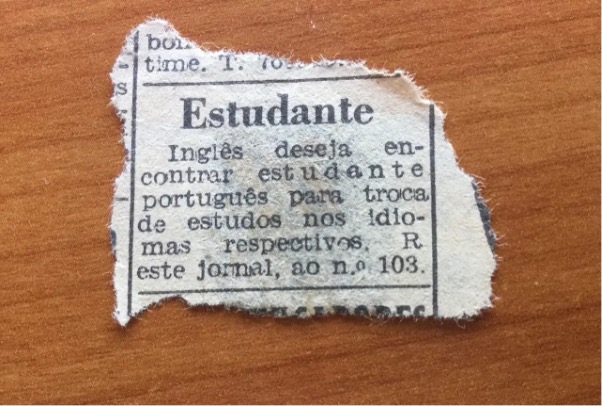

ENGLISH STUDENT SEEKS PORTUGUESE STUDENT

“I wanted to learn to speak Portuguese. So I put an ad in the ‘Diário de Notícias’ saying that I was an English student and that I wanted to get in touch with Portuguese students. It was a way of getting in touch with people I didn’t know. From the perspective of today, it’s hard to understand what Portugal was like during Salazar’s time. But this was the only way to get in touch with young Portuguese people.”

“I received about 30 replies and got in touch with three or four people. In the end, I ended up with two good friends. We’re still friends after all these years.” One of them was called Fernando, he was from Matosinhos and the son of a fisherman. They still keep in touch. “In 1974, he was a militiaman in Lisbon,” recalls the Briton. “After the coup, he took me to PIDE headquarters where the military were examining the documents. I was still able to see some of them…”

The editor of The New York Review of Books called it “A Neat Revolution”. Passages in the text describing “a bloodless revolution” and the “masterful way” in which Marcello Caetano and António Spínola played their role in the last critical hours of the Estado Novo or “the peaceful transfer of authority” contributed to this perception.

In the same vein, in an article entitled “A gentlemanly coup d’état in Portugal”, the American magazine Newsweek wrote in its May 6 edition:

“The Portuguese have always had their own way of doing things. Even that bloody Iberian spectacle, the bullfight, takes on a special, gentlemanly characteristic in Portugal, because the bull is never killed. Last week, a closely coordinated group of army officers applied this civilized tradition to an often violent act: a military coup. Barely a shot was fired, and only a handful of lives were lost when the rebels attacked and – in thirteen hours – snatched ‘control’ of the country from the ranks of the lapsed, ultra-conservative regime that held Portugal in its grip in a feudal system. However, although it was calm and swift, the coup marked a new era in history.”

MILITARY WHO WANT CIVILIAN POWER

In the United States, curiosity about the Portuguese revolution led the media to seek out Maxwell, who had just arrived from Portugal, to explain what was happening in Europe’s last colonial empire. “I gave a few interviews to public television and said it had been a left-wing coup. They were very surprised because they thought it had been a right-wing coup.”

The exceptionality of April 25 was that the military defended the enshrinement of fundamental freedoms, the holding of elections by direct and secret universal suffrage, the immediate amnesty of political prisoners, the establishment of a civilian government and the recognition that the solution to the overseas wars was political and not military. All of this made it difficult for academics, but also for the world’s political elites, to fit the Portuguese case into the existing grids of analysis.

In its coverage of April 25, the American magazine “Time” also placed the 243 pages of Spínola’s book at the heart of the Portuguese revolution. In the article “A Book, a Song and Then a Revolution”, published on May 6, 1974, the book was considered “political dynamite”, “a catalyst for the revolution” and “the death knell of a tragic national failure”.

The cover of the magazine was an illustration of Spínola. The text, as well as dedicating paragraphs to the profile of the “monocle-wearing soldier-hero”, described the popular atmosphere outside the Carmo Barracks.

“Outside, the mood of the crowd was more festive than angry. The spectators spent most of the day curiously watching the tanks and offering cigarettes and sandwiches to the soldiers. When Spínola arrived at the barracks with all the appearance of a De Gaulle-like figure who was not plotting to seize power, but had merely acceded to the conspirators’ call, thousands of people around him applauded frantically.”

International observers’ reading of the events in Portugal may have been hampered by the fact that the coup was led by captains and non-commissioned officers, rather than high-ranking officers, who, in half a day, overthrew a dictatorship that had lasted for almost five decades. This ran counter to the more common practice of military intervention in political processes.

“The coup was organized among young army officers. Nobody knew who they were,” comments Maxwell. “The majority of the army was in Africa, only a minority was in Lisbon. These officers had done several deployments in Africa, had little contact with civilians and even less with underground political parties. The Communist Party was very involved in the Alentejo, but Álvaro Cunhal was out of the country. So was Mário Soares. They were totally taken by surprise.”

WHISTLEBLOWERS HUNTED LIKE RATS

In the pages of the French magazine L’Express, in an article entitled “L’explosion portugaise” (The Portuguese explosion), André Pautard refers to “a strange ambiguity that covers this revolution with uncertainty, in which episodes imitated by the liberation of Paris [1944], the independence of Algeria [1962] or the Sorbonne of May 1968 are mixed together”.

In the May 6 edition, the journalist writes:

“A week after the coup d’état, Lisbon has had enough of parades, speeches and songs. Its inhabitants cover the statues, corsets, lapels and machine guns of the soldiers with red flowers. Former political police informers are hunted down like rats. The marines follow the street demonstrations indefatigably. And everywhere you hear the naive yet threatening slogan that children, civilians and soldiers shout in unison: “The people united will never be defeated”

Potemkine on the banks of the Tagus”.

The British historian recalls how April 25 also took foreign diplomats by surprise. “The American ambassador [Stuart Nash Scott] wasn’t in Lisbon when the revolution happened.

He was in the Azores and didn’t go back to Portugal, he went to Harvard [to chair the annual meeting of the Law School Association, where he studied]. He was unaware of the importance of what he was in the country where he was ambassador.” He wouldn’t return to Portugal until April 29.

Likewise, the head of the CIA in London, Cord Meyer, would admit to having been surprised by the events. He went so far as to say that the captains’ coup “caught the United States at lunchtime”.

IN THE SIGHTS OF REVOLUTION FANS

In 1974, Kenneth Maxwell returned to Portugal in the last quarter of the year. He returned in March-April 1975 to find a different country compared to the days of the revolution. Portugal had become a stage for political confrontation and had become an interesting subject for the international press.

“While in 1974 there were few foreign journalists in Portugal, after April 25 they started arriving. In 1975, Portugal became a hotbed for revolution groupies who started arriving to see the revolution in progress.”

Personalities such as French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez came to Portugal to see and feel the resolution up close. The tourist agency Nouvelles Frontières organized cultural tourism trips to the country, which became a laboratory for political and social analysis for those who wanted to observe a left-wing revolution in Europe.

“Many people arrived with a romantic idea of the revolution. In the Alentejo, the rural workers’ stances were reminiscent of the revolutions of the 19th century, like that of 1848 in France. That was the vision rather than a Russian [1917] or French [1789] revolution. It was a liberal revolution in that sense,” says the historian. “At first, it was difficult for people to understand…”

Born on February 3, 1941 in the small English town of Wellington, Kenneth Maxwell took part in a conference on the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution at the University of São Paulo in Brazil earlier this month. At 83, he continues to be invited to share memories of a unique event. “For me, the revolution itself was a moment of great hope,” he concludes. “It was one of the most important moments in European history in those decades.”

Translated from Portuguese to English by defense.info.