The Australian New Submarine Program: Clearly A Work in Progress

Canberra, Australia

During my current visit to Australia, I have been able to follow up the discussions with the Chief of Navy over the past three years with regard to shipbuilding and shaping a way ahead for the Royal Australian Navy.

During this visit I had a chance to visit the Osborne shipyards and get an update on Collins class and enhanced availability as well as to get a briefing and discussion with senior Australian officials involved in shaping the new build submarine program.

Based on those discussions, I have continued pursuing discussions in Canberra with regard to the challenge of putting in place the new submarine program.

In this article, I will start with the expectations, which Australia is bringing to this new program and what they wish to see in the unique partnership they are forging with the US, France and themselves to build a new design diesel submarine.

The concern with Chinese submarines in the Pacific is real in Australia. And that concern has been reflected both in the decision to build new submarines and new frigates as well as buy P-8s and Tritons for anti-submarine capabilities as well.

The subsurface, surface and air elements are clearly to be blended into a longer reach capability to defend Australia and to work closely with allies seeking to constrain Chinese activities and to ensure freedom of navigation and defense of a rules based order.

Even though the announced decision to build a new class of submarines came before the more recent frigate decision, the agreements in place and in process with the Brits with regard to the frigate provide a clear statement of the kind of partnership, which Australia wishes to see in the shipbuilding domain.

It sets the standard against which the new submarine program will be measured and any final agreements on production and manufacturing, deals which are not yet signed with France as of yet.

The Australians are coming to the new build submarine with several key expectations.

The submarine is to be a large conventionally powered submarine with an American combat system on board allowing for integration with the US and Japanese fleets.

The Commonwealth has already signed the combat systems side of the agreement with Lockheed Martin and the LM/US Navy working relationship in the Virginia class submarine is the clear benchmark from which the Aussies expect their combat system to evolve as well.

The new submarine is not an off the shelf design; it will leverage the French Navy’s barracuda class submarine, but the new design will differ in a number of fundamental ways.

The design contract is in place and the process is underway with Australian engineers now resident in Cherbourg working with French engineers on the design.

But design is one thing; setting up the new manufacturing facility, transferring technology, shaping a work culture where Aussie and French approaches can shape an effective two way partnership is a work in progress.

And agreeing a price for the new submarine, and the size of the workforce supporting the effort in France and Australia are clearly challenges yet to be met.

And with the build of new frigates and submarines focused on the Osborne shipyards, workforce will clearly be a challenge.

Shaping a more effective technical and educational infrastructure in the region to support the comprehensive shipbuilding effort is clearly one of the reasons that the yard was picked as a means for further development of South Australia.

The Aussies are coming at the new submarine program with what they consider to be the lessons of the Collins class experience.

This includes limited technology transfer, significant performance problems and a difficult and expensive remake of the program to get it to the point today where the submarine has a much more acceptable availability rate.

And clearly, the Aussies are looking to be able to have a fleet management approach to availability and one, which can be correlated with deployability, which is what they are working currently with the Collins class submarine.

This is clearly one of the baseline expectations by the Australians – they simply do not want to build a submarine per se; they want to set up an enterprise which can deliver high availability rates, enhanced maintainability built in, modularity for upgradeability and an ability to better embed the performance metrics into a clear understanding of deployability.

The partnership perspective is clearly provided by the agreement put in place with the British with regard to the frigates. Here the UK and Australia are looking to wide ranging set of agreements on working together as well as determining what Aussie assets might go onto the UK version as well.

There is a clear design and build strategy already agreed to and a key focus is upon the manufacturing process and facility to be set up at the Osborne shipyards.

The ship building process, which is part of the UK-Australian agreement, was identified in one article as follows:

Digital shipyards use software to instantly transmit plans across the globe to enable construction with fewer errors, rework, and associated delays and cost increases than has been seen with traditional shipbuilding practices.

It also can involve digital technology to create a “paperless” ship from design and manufacturing to operations and service.

Mr. Phillips said a digital shipyard would ensure every aspect of the ship during the design and construction and throughout its service life was “live and accessible” to crew, maintenance staff and approved suppliers.

“Having a single point of truth in the design phase will mean that each of the nine ships will be replicated, which hasn’t been done in Australia previously, and which will benefit every stage of the program, including the upgrading and maintenance of the ships during service,’’ Mr Phillips said.

“It will also be the first time in Australia where a ship’s systems will have the intelligence to report on its own performance and maintenance needs and have the ability to order both the maintenance and parts required prior to docking.”

The move appears to fit with the federal government’s outlook, with Defence Industry Minister Christopher Pyne yesterday revealing investment priorities for the coming year, including $640m to support the development of “innovative technologies”.

In my discussions in Australia, there is a clear focus upon building a state of the art facility along these lines with regard to the submarine program as well.

This means that the Aussies are not simply looking to see the French transfer current manufacturing technologies to build the new submarine, to co-innovate in shaping new and innovative approaches.

By looking at Asian innovations in shipbuilding, the Aussies would like to see some of those innovations built into their manufacturing processes in their new manufacturing facility.

Put simply, the Aussies do not want to repeat the Collins experience.

They want modern manufacturing processes, which they anticipate with the new frigate and have seen with regard to P-8, Triton and F-35, all programs in which they are a key stakeholder.

The question is can the cultural dynamics of France working with Australia, an Australian with these expectations, be managed to deliver the kind of long term, cross-learning partnership which Australia seeks in this program?

There are clearly key challenges of cross-culture learning and trust to be sorted out to be able to make this partnership work.

From my discussions in Australia, it is clear that on the Aussie side there is a fundamental desire to shape a long term partnership with France in what the Aussies are calling a “continuous build” process.

Here the question is not of a one off design, and then build with the Aussie workforce operating similarly to the Indian workforce in the process of a build as was done by DCNS with India.

If one looks at the frigate contract, at the core of that contract is BAE Systems not simply transferring technology to an existing company in Australia which would then take over the task and execute it, the model is quite different.

The process of the build will see a new entity being created within Australia capable at the end of this process becoming the kind of manufacturing center of excellence which can master maintainability and upgradeability of the new platform for the next phases of the life of that platform.

This process was described in part as follows by ABC News:

ASC Shipbuilding, which is owned by the Australian Government, will become a subsidiary of BAE during the build. Its shipyard in the Adelaide suburb of Osborne will be the hub once production starts in 2020.

The Hunter class frigates are expected to enter service in the late 2020s and will eventually replace the current Anzac class frigates, which have been in service since 1996.

However, the UK Royal Navy is also buying the Type 26, the first two of which are currently under construction. That fleet is not expected to be operational until 2027, which has some questioning whether the Australian frigates will be delayed.

At the end of the building program Australia will resume complete ownership of ASC Shipbuilding, meaning intellectual property of the Australian type 26 will be retained by the Commonwealth.

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-29/hunter-frigate-build-bae-what-you-need-to-know/9923912

This agreement is now becoming the benchmark against any future agreement with France and Naval Group would be measured.

The Aussies are not in a rush and as one Aussie put it to me: “We want the right kind of agreement; we are not interested in the wrong type of agreement.” And when we discussed what the right type of agreement looked like, it was clearly something akin to the UK agreement.

The challenge though is that the Commonwealth has a longstanding working relationship with BAE Systems and the UK. And the UK is part of five eyes, which provides a relatively straightforward way to deal with security arrangements.

According to an article by Jamie Smyth and Peggy Hollinger published by the Financial Times on June 28, 2018, the importance of the broader working relationship with the UK was highlighted.

Michael Shoebridge, an analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, said the decision by Canberra to choose BAE probably reflected some emotional and strategic factors, which went beyond the technical criteria in the tender.

“The UK and Australian defence partnership is long and deep. There is also a lot of emotion around Brexit, which may have played a role given the potential for a deeper partnership with the UK into the future,” he said.

The UK has embarked on a diplomatic charm offensive over the past 12 months in Australia, including visits by Boris Johnson, foreign secretary, and Michael Fallon, a former defence secretary.

It has pledged to upgrade defence co-operation with Canberra and play a more prominent role in the Asia-Pacific, where China has begun to militarise islands in the contested waters of the South China Sea.

The choice of the Type 26 will ensure interoperability between the UK and Australian navies. Gavin Williamson, defence secretary, said the award was a “formidable success for Britain . . .

This is the dawn of a new era in the relationship between Australia and Great Britain, forging new ties in defence and industry in a major boost as we leave the European Union.”

https://www.ft.com/content/845e88e0-7ac7-11e8-8e67-1e1a0846c475

Against this background, the Commonwealth has had a more limited working relationship with France and the defense industry within which France is a key player. It has had experience working with programs in which France is a key player like KC-30A, NH-90 and Tiger. The very good experience has clearly been working with Airbus Defence and Space on the KC-30A, but the NH-90 and Tiger experiences with Airbus Helicopters has not been as positive.

When the Collins Class experience is married to the air systems experience, then the Aussie tolerance for agreeing to anything that is not comprehensive and well thought out is very low.

The challenge for France and Naval Group will be to build a long term partnership which can clearly set in motion a new working relationship which is not framed by these past experiences, but can leverage the very positive KC-30A working relationship. The KC-30A is obviously different from the submarine because the plane was built abroad and the working relationship very good with Airbus Space and Defence where the Aussies are a cutting edge user pushing the way ahead with the company to shape future capabilities.

That is also the challenge: is Naval Group really a company like Lockheed or Airbus Defence and Space?

Or is the French government involvement so deep that the working processes with Naval Group not be transparent enough and credible enough to shape the kind of partnership the Aussies are looking for?

The change in status of Airbus, notably under the leadership of Tom Enders, has clearly underscored the independence of this key European company and Naval Group has more of a challenge demonstrating its independence to deliver not a product nor a build of an existing product on foreign soil, but an open-ended partnership able to shape and evolve a new build product where the digital processes of build and sustain are so significant.

President Macron put it this way with regard to the partnership: “As President of the republic, I will do everything to ensure we make the necessary arrangements to meet the requirements of this contract but more broadly, to accompany you in this strategic partnership.”

President Macron has clearly emphasized the Chinese challenge and has been very visible in working relationships in the region, notably with Australia and India.

The political intent is clearly there.

Yet it is to be remembered that Australia downselected the French team under the previous government and now they are dealing with a different government although the same DCNS/Naval Group.

But there is a new DGA team, and their engagement seems to have grown in the negotiations and complicated Aussie perceptions of the negotiating process.

The Aussies downselected the French option because it provides a good way ahead.

The French correctly understood the emphasis which Australia was placing on designing and builder a larger submarine than either Germany or Japan was offering; and the desire to have a regionally superior submarine for the Aussies is not simply about the design and the initial build.

It is about having a regionally superior submarine enterprise which embraces design, upgradeability, modernization, production, sustainment and redesign as enabling what they refer to as a continuous shipbuilding process.

There is little doubt that the design part of the bid can be met; the challenge will be building the kind of enterprise and ongoing partnership, which Australia wants for it, is not simply a historical repeat; it is blazing new history and new industrial approaches.

It would be shame if the right kind of partnership is not put in place to achieve what the Australians needs – a new capable submarine which can deliver operational superiority in the region.

And for the French, the benefits of working with a key partner investing and working a way ahead in shaping a cutting edge approach can provide reverse technology transfer opportunities, notably with regard to manufacturing processes in the years ahead.

But this is a work in progress, or not.

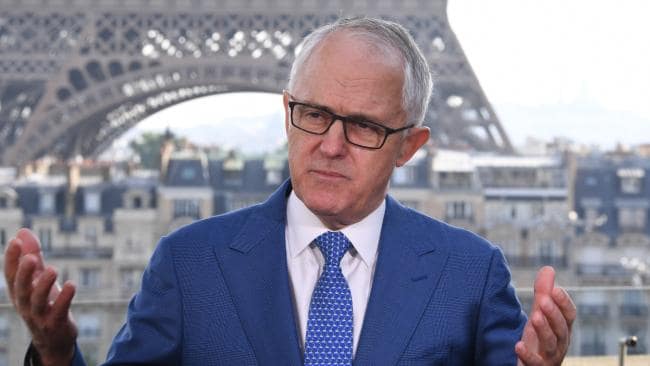

The featured photo was from Malcolm Turnbull’s visit to France in July 2017. Picture: AAP

Dr. Laird is a Research Fellow at the Williams Foundation and is in Canberra to attend their latest seminar and to prepare the report on that seminar.

For the upcoming seminar, see the following:

The Imperative for an Independent Deterrent: A Joint Strike Seminar August 2018