Warlords Series 1: Turbo Tomassetti Looks Back at His Career and the Way Ahead for the F-35

Second Line of Defense recently visited 2nd Marine Wing, including MCAS Beaufort.

We visited the 2019 airshow as well as interviewing the current CO of VFMAT-501, Lt. Col. Adam Levine.

On the occasion of that visit and the opportunity to get an update from the CO, we are going to look back at our various visits to the squadron and the standup of the F-35.

We started by visits at Eglin AFB where the squadron was first stood up prior to its move in 2015.

It is most appropriate to start with the “godfather” of the effort, Colonel Tomassetti and the articles we published June 2013.

This is the first article in the series of retrospective look backs.

“Turbo” Tomassetti Exit Interview

2015-03-13 By Robbin Laird

I have had the opportunity to track the evolution of the Osprey from seeing a small number of planes on the tarmac at New River to watching it mature and revolutionize the assault force.

It is clear that the F-35B will have a similar trajectory with the USMC.

Watching that growth and development path has been facilitated over the years by meeting with, and talking with Art “Turbo” Tomassetti when he first came to Eglin AFB and now after the end of his distinguished Marine Corps career he is working the F-35B issues from the Lockheed Martin side of the fence.

When I first met “Turbo” in 2010 there were very few buildings at Eglin to support the F-35 program.

Now planes are coming out of the production chute and the services and the partners are working with the planes and preparing for their entry into service.

In this interview, “Turbo” provides an update on the F-35B preparing for entry into service and provides some perspectives on the way ahead, as he always done in our interviews.

Question: When I was at Fort Worth recently, you were traveling. I assume that with the Marines focused on the entry into service of the F-35B this year, you are making the tours at the key spots where the plane is coming to life and getting ready for IOC?

Tomassetti: That indeed is what I am doing.

My typical flow is I try to get to the places where we have the airplanes operating every month and each is for a different reason.

I visit to see how they’re doing on progressing to close out SDD at Pax River to Beaufort to check on Pilot training and to Yuma to see how they’re progressing on preparation for IOC and OT-1as they will be the predominant entity conducting that event on the USS Wasp in May.

OT-1 will be a team event with personnel from OT in Edwards and from VMFAT-501 from Beaufort supporting as well.

The key focus of OT-1 is verifying that we can take the airplanes, move in from a land home base, put them out at sea, operate them at sea, and bring them home, which is what the Marine Corps would do in most cases, should they be called upon to go support an activity somewhere on the globe.

I will be at Yuma next week and looking to find ways we can support them most effectively.

Question: There is a story out there which highlights that the Marines are drawing upon USAF maintainers in getting ready for USMC IOC.

To the unvarnished eye this is a negative comment, but does this not highlight one of the goals of the programs, namely cross service and cross partner maintenance approaches?

Tomassetti: It does.

As we talked about when I was at Eglin, a clear opportunity with a joint aircraft it is to have joint maintenance.

Commonality allows you to do things that you can’t do if you don’t have common airplanes.

The notion that every base is an isolated entity unto itself and that people will only have expertise to do their own thing is something we need to get past.

I think the world in the future is going to demand a lot more integration and cooperation than we’ve seen in the past in order to be successful.

That provides options as well. If you look at F-35 as a common global system, that’s much different than looking at it as an isolated system or one-off thing that has unique support requirements.

I think back to the days of Desert Storm where everybody came to play, but not everybody could play together because we didn’t have the interoperability that is built into this system from the ground up.

Question: A challenge of building a software upgradeable program is to understand how capable the initial planes actually are. They will progress over time, and in a real sense never be finished.

How capable do you see the initial F-35B to be deployed by the Marines for combat?

Tomassetti: I hear the same things and people say, “How can you go initial operational capability before you’re done developing the airplane?”

I agree with you we should really never be done developing airplane.

We should always be looking to improve it and that is the plan going forward.

We already talk about follow-on developments because we know technology’s going to change, tactics are going to change, the threat’s going to change.

We have to keep up with that.

The airplane never becomes static in terms of its growth.

Why would the Marine Corps declare IOC with something at this stage of the game?

I think you have to look at, if called upon to go someplace and do something. You are the person in charge. You would like to send your best assets forward.

Your best assets are those that can accomplish the mission and the ones that can keep your people safe doing the mission.

Look at what the Marine Corps has in its inventory as an example look at the airplane I grew up in, the Harrier. I went to Desert Storm in a Harrier that was a day-attack airplane.

It did not have systems to conduct night operations yet we conducted operations at night.

It is a subsonic airplane with a limited weapons envelope, but it got the job done because the people were well-trained.

The airplane was the best it could be at the time, and that’s what the Marine Corps had in its arsenal to do the job with.

Now the F-35B is in the Marine Corps’ arsenal and they look at the best platform to go do whatever the mission is.

I think today, the F35B has all of the attributes to excel in a number of mission areas and why would you not choose to send your best system out to accomplish the mission?

I think that’s where the Marine Corps is and that they realize that the airplane today is already getting to the point where it’s meeting or exceeding the capabilities of legacy airplanes.

In addition to that, knowing that you’re probably going to send the F35s with a mix of what you already have. Having the F35 out there with the legacy airplanes only makes the legacy airplanes better.

From the outset, the F-35 will have an additive effect in the battlespace and will enhance the lethality and survivability of the other air assets and of the ground force as well.

Question: Another aspect, which is confusing, is the notion of IOC itself. IOC is a beginning point; not a statement of full maturity.

How should one interpret IOC?

Tomassetti: I try to tell people that if you go to Yuma on the day before that declaration and look around the squadron and look around the Flightline and go the day after the declaration, and look around the squadron and look around Flightline, I don’t think you’ll see anything different.

But what does change is the status of the squadron.

That squadron knows that they can be called upon to go somewhere.

That squadron commander knows his squadron is conducting their training when they’re evaluating their readiness, when they’re doing their inspections, when they’re participating at exercises, whatever the case may be. He’s looking at it through the lens of my folks need to be able to, if called upon, go someplace, and be effective and to meet the mission objectives.

That puts your mindset and how you approach what you do day-to-day in a little different prospect than, “Hey, I’m still just in this developing, maturing, on-my-way to something phase where my flying is mostly just focused on expanding my knowledge on the airplane.”

Now the squadron commander and his team are focused on going somewhere and doing something effective in support of the deployed force.

It is not about tests; it is about mission success.

Question: I want to return to the challenge of understanding software upgradeability. There is a constant problem of understanding that blocks of software are simply bundles of added capabilities; they are not the definer, a level of maturity necessary to use the airplane.

How do you view the growth process after IOC?

Tomassetti: When you have the airplane in hand and actually start using it, you’re going to do what you do with every other system, once you have it; you learn how to maximize what it can do.

It may or may not be what you envisioned in the initial proposition. It may or not be what you envisioned during development, but when you get the airplane and you’re operating it, you will find the way to get the most out of what that airplane can do.

The other key is that now as we put to the airplane and the ALIS 2.0 version of maintenance in the hands of the squadron in Yuma, they now become part of the process. I’m not saying that they haven’t been, but they’re now in the realm of we’re also now being able to contribute to the next iteration of the airplane.

They will find things out.

They will be part of the solution to make the airplane better as we move forward.

That’s a good thing, because while the Developmental Test team does their piece and a lot of what I just talked about is the things we would normally expect, the Operational Test team to do, because of where we are and how the program’s been set up, you now also have fleet squadrons that can contribute to that knowledge base and maturation process as well.

We just need to be able to collect all that information, make sense of it, and then figure out how to make the airplane better based on all that experience.

If you looked at the mission of the airplane and whether you talk about it in air-to-air or in an air-to-ground sense, it has to be able to locate, identify and prosecute targets. Today, that’s not necessarily achieved by making the wings bigger or making the tail different or changing the configuration or the look of the airplane.

It’s done by changing the systems, the inside of the airplane, making the processors faster so that they can go through that cycle faster, which makes enables it to find and execute against targets more rapidly and more effectively.

And this true not just for the F-35, but for the information it can deliver to the other aircraft it operates with to make them more effective.

Identifying the target is probably the real key here, is not only tell me that what’s out in front of me: is it a tank , is it a truck , an airplane or a ship but tell me what kind of tank it is. Tell me how fast it’s moving or how long it’s been parked where it is or if it’s getting ready to fire. That kind of information processing is going to be done pretty much through software, not through bolting something on the airplane or changing the shape of something on the airplane.

What you’re going to do now is use and control the electromagnetic spectrum by changing boxes and software inside the airplane that no one will ever see from the outside.

You’re right. It’s a little bit different because folks in the past when you change airplanes, they’re used to seeing that change.

They see that new pod or new bump or that new antenna or it got bigger. It has more pylons or those kinds of things.

I don’t think you’re going to see the same thing in the lifecycle of F-35.

It’s going to keep getting better but as you described, it’s likely going to look the same from the outside.

Question: We put in our latest Defense News commentary the simple proposition that the F-35 is coming at a point for the services and the partners where they are looking at its contribution to the transformation of their forces, not simply adding a silver bullet to the holster.

How do you view the transformation process?

Tomassetti: It is twofold.

On the one hand, it is about operating legacy aircraft with the F-35 and learning how to make these legacy aircraft better and to use them differently as the services learn what the F-35 does and how it does it.

For the Marines, this means that the Av-8Bs and F/A-18s, which remain in the force, will not be used the same way they have been used before. You have to figure out how to integrate them. Understanding how do they operate differently and more effectively with the F-35s, and how do the F-35s draw upon the legacy aircraft to gain more significant effects from operating together.

On the other hand, the F-35 is simply not like a legacy aircraft. We need to learn how to operate them together to learn their special effects when so doing for joint F-35 operations, or anticipating the day when we have an all F-35 fleet.

The pilot and maintainer evolution will be critical to this as new pilots and maintainers enter the force now with no history/habits from legacy aircraft.

All of us old folks carry a lot of baggage from wherever we came from. It’s not a good thing or a bad thing. It’s just reality.

We’ve carried that with us. It shapes how we think about things. We’re going to bring a breed of folks into the airplane shortly that is going to have a fresh perspective, that is a different generation which grew up with X-Box 1 and Play Station not Pong and Space Invaders. They’re used to processing a lot of information.

They’re used to speed in information.

They are going to find out ways to do things with this airplane that we haven’t even thought of.

We have these big milestones we’ve got to track through to be successful in that but what those youngsters are going to bring to the table when they get their hands on this airplane and start putting their new perspective on it I think is going to be dramatically different over time.

“Turbo” and “Easy” Focus on the Role of Squadron Pilots Driving Innovation

6/26/13 During a visit to the 33rd Fighter Wing, an exit interview with Col. “Turbo” Tomassetti provided a unique opportunity to look back on the career of “Turbo” and the way ahead for the F-35B within USMC aviation.

A key part of the interview was provided by an exchange between “Turbo” and “Easy” Ed Timperlake, a former USMC aviator and reserve squadron commanding officer.

The exchange provided a good chance for non-pilots to understand the key role which the exchanges in the ready room play in shaping the evolution of combat training, approaches and capabilities for an air combat force.

“Easy”: The “right stuff” is the best way to understand how it feels when you start in the ready room and then move forward in your aviation career. Could you take us back to your experience when you started? What did it feel like to enter your first ready room and begin your career?

“Turbo: I’ve had a lot of time to reflect here in the past few weeks on things.

I remember when I got to Harrier training. What they would try to do is to get everybody in the backseat of one of the two-seat Harriers just for an exposure ride or two before starting the class.

And I remember getting the opportunity to get in the back of the Harrier on a flight, and it was a four-ship training flight, and I don’t remember specifically the mission of the day. But just sitting in the cockpit, coming out of the TA4 as my sort of last airplane experience a few months prior, sitting in the cockpit and seeing an electroninc display screen, and a heads up display (HUD) in there. I thought I was in the most high-tech thing I had ever seen in my life.

And when I had that first sensation of getting pressed back in the seat on a short takeoff, it was like wow, this is incredible. I’ve seen these airplanes at air shows as a kid, and that’s sort of why I put it down as my choice to go fly.

But an interesting anecdote, the RF4 was my first choice But the class before me was the last class they assigned anybody to the RF4 in because they knew it was timing out. Harrier was my second choice, so I ended up heading to Cherry Point.

The ready rooms were big because there were lots of different folks in lots of different phases. But there at Harrier training, there were only about three classes in session at any given time, given the length of the course.

And you were in with a small group of folks. And chances are, you were going to end up in the same squadron as at least one of those other folks.

I was fortunate that three guys out of my Harrier training class went to the same squadron because that was where the need was.

You started to get a sense of that camaraderie and a sense of what it meant to sit there on a Friday afternoon before going over to the officer’s club or whatever the deal of the day was and talk airplane stuff with bubbas who had the sort of same goals and mindset that you have. That is where it started and I vividly remember those moments.

“Easy”: “With the second tour, sitting in the ready room, and discussing flying the airplane, you understand the airplane better, and you’re learning from squadron mates who may have been exposed to a different set of experiences in his or her career path — at the ’03, ’04 level– You guys must have seen that a lot in the Harrier community.

“Turbo”: I got about six months extra time with the squadron than most people normally got just because I was waiting on a school seat for the summer. . I got 1,000 hours in that first tour, which was virtually unheard of in the Harrier community.

With the squadron I went to a six-month deployment to West Pac, three months to Canada in Cold Lake, nine months to Desert Shield, Desert Storm. And for that whole three and a half years I was with the same guys. Our squadron came back from West Pac, turned right around and went to Desert Shield.

In other words, in the summer that we should’ve been doing the big turnover of people, it never happened because we preserved everybody in the squadron to go to war.

So I remained in the junior group of pilots in that squadron for my entire tour because nobody new came in until the very end there when we got back from Desert Storm.

But I remember very well being challenged and starting to get a sense of where I stood in the realms of aviators in that first tour. It was mostly all about me. And again, I was finding out how good I was or wasn’t; I was finding out what my limits were with what I could do with that particular airplane. And so largely, I was finding out what the limits of that airplane were and what my limits were.

We were a band of brothers, we did all this stuff together, and we had an incredible level of team that you don’t come across very often.

The second tour, I think, because you feel you come back in now as a trainer, a leader, and there are folks younger than you, you start to get a glimpse of the bigger picture.

You start to have more responsibilities outside you and your airplane.

And you start to figure out what where you fit in the grand scheme of this thing called the MAGTF.

With my second tour is where that sort of ah-ha moment occurred that I realized that it wasn’t just about me and what I could do in my airplane, there was something bigger out there within which I fit.

“Easy”: Col. could you look back from that experience to your latest one as preparing the pilots for the F-35? Could you compare and contrast your experience with what you are seeing with the new F-35 pilots?

“Turbo”: I think one of the interesting things right now that is a little bit different than anything else that I encountered along the way is the mix of pilots in the ready room here at 501.

When I entered the Harrier community, we were still merging the A4 community into the Harrier community, so in my training class for Harriers, there were three transition A4 pilots, and three new guys.

There was a blend going on of older transition pilots and new pilots being injected into the system. But they were all basically attack pilots coming from very similar backgrounds.

For new guys like me, we didn’t have a philosophy yet, but we understood the difference between fighter and attack, since you had to make a distinction back then.

But now I sit in the ready room at 501 and simple things stand out.

Everybody’s left shoulder has either a MAWTS patch or a Test Pilot School patch or both. There isn’t a squadron in the Marine Corps, outside of MAWTS itself where everybody’s wearing a MAWTS patch.

The next observation I would make is that you’ve got an even blend of Harrier pilots and F-18 pilots. And you’ve got the different sort of nuances of F-18 pilots. You got single-seat and two-seat pilots, and you’ve got boat deck pilots and shore-based pilots.

We have a confluence of all of these different ways of thinking about an airplane and what it means to fly that airplane and be part of operations.

This means that there are a lot of good ideas out there, and there is a lot of baggage out there; and that all comes together in the ready room.

It’s interesting to watch when something not clear-cut. They have a standardization board and they want to discuss some particular way to train and maneuver or a particular way we should be doing something with the airplane. And there’s no clear-cut answer. It didn’t come handed to us in a flight manual; the test guys didn’t already develop the way to do it. It’s up to the squadron to decide what to do.

And I’ll tell you, there are some interesting and heated discussions between all of the different types of pilots that are sitting in the ready room. And that is a good thing.

I think that uniqueness is going to set us off on a footing with this airplane that perhaps the V22 had a similar sort of start. The fact that we started flying here over a year now at Eglin, we are introducing the operational F-35. And the fact that the pilots in the 501 ready room are putting their fingerprints on everybody who is going to fly it, at least for the next several years, They own the training for F-35,, They are going to set the foundation.

Obviously, at some point in the future, things will normalize and you won’t see all those patches sitting in the flight ready room together.

I don’t know that we could’ve done the beginning of this airplane any better in terms of the people and how it is getting introduced and how the airplane is meeting the pilots.

“Easy”: I couldn’t agree with you more. I lost a very close Academy Classmate to the AV-8, Tom Tyler. Obviously, the F-35B flies much easier than the Harrier, which is a major step forward. With a serious improvement in the ability to fly the aircraft, and that will allow the pilots to deal with the other capabilities of the aircraft more effectively. What is your take on this evolution?

“Turbo”: I think there’s sort of three distinct phases we’re going to go through, the way the program’s set up in the beginning. You’re going to have the phase where we have all these transition pilots coming from other platforms who come with baggage. And we got to convince them to let go of that.

And then, in the next phase you will have to expose to them and explain to them the new thing, then new capability. And finally, you have to give them time to embrace the new thing. So, I think that’s what’s going to happen.

And right now, we’re sort of in between phase one and two. We’re sort of getting people to let go of whatever they came with. Not let go of everything because there’s a lot of best practices out there we do want to harvest, but you haveto reopen your mind to new possibilities when you come to this airplane.

And we’ll do a good job here of doing that with the systems we have and the training system that’s in place. We will be able to explain what the new thing is. That’s in the classroom, that’s in the simulator, that’s in the sidebar discussions in the ready room, all of that.

The fact that I have been successful in convincing the Marine Corps to inject a few developmental test pilots in here, who had finished their DT tour, so that we didn’t sort of lose all that experience and expertise. So that now you’ve got folks in the ready room who can give you the sort of background on things and why they are the way they are, and how they’re going to get better.

We’re going to start with what we left off with in our other airplanes. We’re going to start with training a person with a number of flights and in the way we did it in the Harrier and Hornet because people need to press the I believe button on this new system, and you have to give them time to get there. You have to let the airplane sell itself

And it will. I mean, the V22 sold itself out of all of its demons of the past. It wasn’t because somebody said something in some newsprint article, it wasn’t because somebody said something in a meeting. The airplane sold itself based on its performance.

And the F-35 is going to do the same thing. It just needs to have the opportunity to do that.

I think we’re going to find that pilots are going to get out there and they’re going to see that hey, this syllabus says you got to do 20 landings in the first three weeks in order to get your mastery of this. And by the third landing, guys are going to go okay, that was a perfect landing. I don’t know really why we’re going to continue to practice this for 17 more tries.

I think we’re going to have to let it evolve over time, but I do believe that we are going to get to that point where we’re going to look at this airplane as its own unique entity, and start training to what it allows us to do.

The goal — I know why the Marine Corps wanted an expeditionary airplane, I get it because I grew up in that environment, but I will tell you, the sort of personal stamp that I have tried to put on this thing since I joined the program in 1998 is I wanted a STOVL airplane that could do all the things that the Marine Corps needed, but was easy to fly.

Because like you said, I went to three memorial services in my first year in the fleet. And that was painful, and that hurt because I knew those guys and I lived with those guys.

There were some shortfalls of the airplane, there were some shortfalls in our training, and again, it was airplane that really demanded that you were on your toes every single minute you were in the cockpit.

And we’re smarter than that now; we’re better than that now. A little bit because computers are better than they used to be and what we can do with computers and airplanes are better.

But the whole point of building this particular STOVL airplane, From my view and the other Harrier pilots in the developmental phase was to make it easy to fly. We knew what the price that the people who flew that airplane paid, and we didn’t want to see that repeated.

Simple things like hey, the airplane won’t let you decel to the hover if you’re too heavy. A simple safety feature like that, might have saved people in the Harrier

And the fact that we’re smart enough now to figure out how to incorporate that into an airplane and make it work and the fact that I have a STOVL airplane that I don’t need three hands to fly like I did in the Harrier.

I got an airplane that you tell I want to go up; I want to go down, I want to go forward, I want to go back, and it says I got it. I’ll figure out what to do with all of those things that can maneuver and wiggle. And you just tell it what you want it to do.

I think we need to give the airplane time to sell itself, and we need to give the folks a chance to digest what that means, and then go back and take another look at how we train people to fly it and realize that we’re going to spend 90 percent of our time talking about tactical capability of the airplane and about 10 percent talking about takeoff and landing.

Editor’s Note: The subtitle of this article could be “Cubical Commandos Need Not Apply to Become USMC Aviators”

“Turbo” Assess the Past and Looks Forward to the Future of Marine Corps Aviation and Its Contribution

2013-06-27

“Turbo” has been on the builders of the F-35 in the USMC in every sense of the word.

From being an X plane test pilot to one of the key officers involved in the build out of the Eglin training facility, “Turbo” has clearly left his imprint on the program and on the future of U.S. airpower.

In this interview, we provide an overview of his assessments of the past and the prospects for the future.

SLD: How does the F-35 impact on the expeditionary capabilities of the USMC?

Turbo: I think when you look at the F-35 airplane, you have to look at it in terms of what does that airplane bring to the battle space.

People want to measure airplanes with the standard sort of metrics of how fast does it go? How well does it turn? How many of this or that can it carry?

The F-35 goes beyond that.

And when we talk about what it brings to the Marine air-ground taskforce, you have to look at what does that airplane in the battle space mean to that Marine on the ground with the rifle and the radio? What does that airplane in the battle space mean to that Marine in the tank or in the armored vehicle?

It means that he or she has access to information they might not otherwise have because that F-35 is there.

It means they will have visibility into target sets and spheres of influence beyond the range of what they would normally have access to before.

And when we talk about the F-35B, we’re bringing that airplane up close to where the troops are because of its expeditionary nature. Because it can go from amphibious ships, it can go from expeditionary airfields, troops will have access to that airplane, they have access to what that information that airplane brings to the table.

It will open up a whole new world of possibilities in the battle space.

What that brings to the Marine air-ground taskforce is a degree of insight into the battle space and ability to affect the battle space that we have not had before.

SLD: How would you contrast the options and capabilities you had at that time you started as an aviator with what a young Marine Corps aviator will have when he or she goes with the first F-35B squadron to Japan?

Turbo: When I started in Marine aviation, my first airplane was the Harrier. And I thought that airplane was the most high tech incredible airplane I had ever seen. It had a single screen in the cockpit; it was basically an analog airplane with a few digital enhancements. It had a heads up display; it had some interesting ways that you could designate a target on the ground and some automatic sort of weapons engagements things. It wasn’t purely manual aimed and manual deliver weapons as some other airplanes of the past were. It had a little bit of digital enhancement.

And there was information available to me as a pilot. I could get some information about what was going on inside my airplane. I had a limited bit of information of what was going on in the world around me.

And when I look now at what the F-35 brings to the table, it’s a completely digital airplane. The analog world is in the past.

And the amount of information that’s available to the pilot and the cockpit, it’s almost mind-boggling. From the touch screen display that sits in front of you with the ability to open14 windows of information you get about the aircraft, or about what’s going on in the battle space around you.

And the pilots have access to all of that. They have access to whatever their airplane is seeing and sensing around it. They have access to the other F-35s they’re flying with, the information that they’re seeing and sensing. And all that information is available to the pilot.

I couldn’t even envision that amount of information, that amount of situational awareness of the battle space back in the days when I was flying the Harrier.

Everything was small then. The airplanes were close together. The area that we could see and sense and understand was small circle around the airplane.

Now, the airplanes are far apart. Now that area that they can see and sense is almost limitless considering that they can get information from off board platforms and beyond the horizon.

It’s a whole new world of having situational awareness when you’re flying the airplane.

SLD: From the time you flew the X plane, which is now in the Smithsonian, to the reality of an F-35B, what’s the biggest difference concerning what you imagined and what you actually see on the flight line?

Turbo: We wanted to build an airplane that was easy to fly and an airplane that was easy to maintain. If you build an airplane that’s easy to fly, your accident rate comes down. Your requirements for training come down. And in the long-term life of an airplane, if you can reduce those two things, the cost of everything comes down.

And what we can do today with fly-by-wire technology digital flight controls is, again, it’s leaps and bounds over where we were 20 years ago when we first started with fly-by-wire airplanes.

Right now, we have an airplane that the pilot says I want to go here, I want to do this, and the computers make all that happen. And the airplane goes where you want it to go.

And I think as much as we hoped for that, we all knew that that’s a hard thing to make happen. It sounds like a very simple concept; build an airplane that’s easy to fly, why don’t we do that all the time? Well, in practice, it’s very complicated because airplanes today are complicated machines.

And we demand a lot out of them in today’s environment. The fact that we’ve achieved that is great.

I had no concept of what this thing called sensor fusion was really going to mean when you sat in the cockpit. It’s a combination of what the sensors tell you, it’s a combination of how the information’s presented on the flat panel display in front of you, and a combination of what you see in your helmet mounted display.

It is all those systems working together. What you know as the pilot, now, compared to what I knew as a pilot in the prototype or what I knew as a pilot in any other airplane I’ve ever flow, again, it’s in a league all by itself.

And I will tell you, I think we have got the airplane to the point where you can start to really see how how all those systems will come together.

SLD: How hard has it been to change the mindset of the pilots now learning to fly and use the F-35?

Turbo: I think one of the interesting things in the beginning, with any new program, is that you start with pilots who have flown other airplanes. You transition experienced pilots into your new system.

And they all bring baggage with them, for lack of a better term. Everybody brings what they know from their legacy airplane. They’ve grown comfortable with whatever that is.

When you give them new capability and new technology, first you’ve got to figure out how to convince them to let go of the old, so that’s one step. Then you’ve got to explain the new to them and what it means and what it can do for them. Then you have to give them time to embrace that.

I think today we’re between that stage of letting go of the old and explaining the new. And we need to give it a little bit more time for folks to see all that in practice and then come to embrace that new technology and what it means and the capabilities that it gives them.

But they’re also the generation that grew up with smart phones.They’re the generation that grew up with all the advanced video game technology that we have today. They grew up having the ability to assimilate lots of different information in graphic format in front of them and manipulate that information and be comfortable with it.

I think they’re going to be the first real indication of folks who can step right into embracing the new technologies and those new capabilities and what it can do for them. I’m excited to see those first youngsters get into the airplane that don’t have any preconceived notions, that don’t have any of that undoing of the old way of doing things that has to occur and see what they can do with the airplane.

I think we’re going to learn a lot more about what you can do with an F-35 when that generation of pilots hits the flight line.

SLD: Do you think a fleet concept is perhaps a good way to kind of capture to sharing your data aspect of the aircraft?

Turbo: I do. It’s too easy to just fall back to what you know when you want to talk about an airplane. You want to talk about, again, the basic performance parameters of speed and turn rate and those kinds of things.

With the F-35, you have to get to the next step. You can’t look at it as just a single airplane.

And even if lots of different people are buying that same single airplane, they need to get past just the fact that hey, we can go the same speed and we can turn at the same rate.

And we may develop some similar tactics because of that. We now have to look at the fact that the airplanes can gather, collect and share information.

And they can share that information with any other F-35 out there and to some extent with just about anybody else out there. And you have that capability because you have the same platform, because you have that commonality.

That’s something we’re not used to having. It’s not just the fact that we can talk on the same radio frequency. We’re sharing information over data links. We’re sharing information collected from a variety of sensors that’s been processed already before it’s sent over to the rest of the people who are going to view it. The F-35 has that capability.

We will need to learn how to use that capability of a group of airplanes, regardless of where they launch from, regardless of whose insignia is painted on the outside. You need to harness the energy that that group of airplanes brings to the battle space.

SLD: A Navy pilot as deputy commander is replacing you. Doesn’t that represent the next phase in the program with the inclusion of the F-35C within the overall F-35 program?

Turbo: I represent the last of the initial folks who came to Eglin to get it started. The services did a great job of sending people here who were builders. Perhaps we were not the best at streamlining and making things efficient, so that’s what the new crowd’s going to do.

You need to take the place to the next level. And again, we’ve talked about and you need to stop talking about maturing and developing, and the initial stages and start talking about you’re a training organization responsible for making a quota of trained pilots and trained maintainers every year.

And you need to start thinking about this place in those terms.

My successor brings a wealth of experience as an initial F-14 guy, and then later, F-18 guy as a CAG. He comes understanding what Naval aviation means. And I think his perspective here along with the new Air Force wing commander; I think that’s going to continue to help give the airplane the opportunity to sell itself.

SLD: As the plane progresses it will be increasingly capable of EW functions. We would assume that you would add pilots with that sort of background to the program as well.

Turbo: As you know they are already doing that at MAWTS, and we will do that here as well. And I don’t think it’s too early to start because what you want is those folks who understand that mission, the electronic attack mission from a completely different perspective than any Harrier or F-18 person might. We need to be there at the ground floor as well because you want the initial foundation to be laid by people who know what they’re talking about.

I think we’re getting to that point with the block 2 airplanes where some of those capabilities are available. Even if it’s just available in the simulator for a few months before it’s out there on the flight line, those folks are starting to figure out how are we going to teach somebody electronic attack type capabilities in the simulator because it works in there in the beginning.

Who better to have than the folks who do that for a living doing the teaching?

SLD: As you look back, what are some of the lessons learned that you would pass on to your successors?

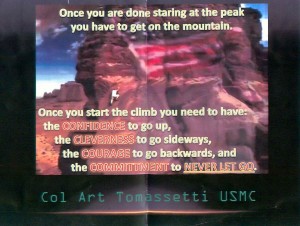

Turbo: I ended my retirement speech to the Marines in 501 with the analogy I’ve used to describe this place and the effort here at Eglin.

I use the rock climbing analogy. For a long time, you can stand there and look at this big mountain peak in the distance. And that’s what was going on in an F-35 five, six, seven years ago. People were just sort of staring at this enormous thing in front of us.

At some point though, you got to put your hand on the mountain and start climbing. And you got to have the confidence and the skill to continue to move up. You got to have the cleverness to move sideways from time to time because that’s what it takes. And you got to have the courage to move backwards on occasion because that’s what it takes to find the way to the top.

But the one thing you cannot do once you have started to climb, is you’ve got to have the commitment never to let go.

I left everybody with that message on numerous occasions and that’s how I close out my retirement speech. And I believe that describes where we are at today.

We’re on this mountain, we still got a ways to go to get to the top, anybody who has decided to climb just needs to hang on and use those skills to keep moving forward.

The featured photo shows a wet Major Art Turbo Tomassetti waving a U.S. Marine Corps flag and holds a hockey stick following his first vertical takeoff, hover and vertical landing in the X-35B on Friday, June 29th 2001. [LMTAS photo]

Colonel Arthur Tomassetti retired for his last position which was the vice commander of the 33rd Fighter Wing, Air Education and Training Command, Eglin Air Force Base, Fla. The 33rd Fighter Wing serves as the home to the Joint Strike Fighter Integrated Training Center, providing pilot and maintenance training for nine international partners.

Colonel Tomassetti earned his commission from the United States Navy Reserve Officer Training Corp in 1986. He completed flight training in Beeville, Texas and Pensacola, Fla. He became a pilot and trained in the AV-8B Harrier in Cherry Point, N. C. He’s served with two Fleet Harrier Squadrons VMA-542 and VMA-513.

Colonel Tomassetti served as a member of the Joint Strike Fighter Test Force and became the lead government pilot for the X-35 Test Team. He was the only U.S. Government pilot to fly all three variants of the X-35 aircraft and flew the first ever Short Take-Off, level supersonic dash and vertical landing accomplished on a single flight.

Colonel Tomassetti was a designated USMC Acquisition Professional Officer holding Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (DAWIA) level 3 certifications in Test and Evaluation and Program Management

He was a command pilot with more than 3,200 hours in 35 different aircraft.

EDUCATION

- 1986 Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering, Northwestern University, Ill. 1986 USMC Officers Basic School, Va.

- 1988 USMC AV-8B Flight Training, Cherry Point, N.C.

- 1992 USMC Weapons and Tactics Instructor Course, MAWTS-1, Ariz.

- 1993 USMC Expeditionary Warfare School, Marine Corps University, Va.

- 1997 United States Naval Test Pilot School, Patuxent River, Md.

- 2001 Master of Science degree in Aviation System, University of Tennessee, Tenn.

- 2002 USMC Command and Staff College, Marine Corps University, Va

ASSIGNMENTS

- Jan 1987-Aug 1989 Flight Training Student Fla., Texas, N.C.

- Sept 1989 – June 1991 Flight Officer VMA-542, Cherry Point. N.C.

- June 1991- Jan 1992 Director Safety and Standardization VMA-542, Cherry Point., N.C.

- July 1992-June 1993 Weapons and Tactics Instructor, VMA-542, Cherry Point, N.C.

- July 1993- June 1994 Student Expeditionary Warfare School, Quantico, Va.

- June 1994- Oct 1994 Asst Operations Officer, USMC Officers Candidate School, Quantico, Va.

- Oct 1994 – Dec 1995 Weapons and Tactics Instructor, VMA-513 Yuma, Ariz.

- Dec 1995- Dec 1996 Operations Officer VMA-513, Yuma, Ariz.

- Dec 1997- Dec 1997 Test Pilot under instruction, Patuxent River, Md.

- Jan 1998-Aug 2001 Test Pilot Joint Strike Fighter Program, VX-23, Md.

- June 2002 – June 2004, USMC JSF Program Integrator, Lockheed Martin, Fort Worth, Texas.

- June 2004 – Dec 2005, Chief Test Pilot, VX-23, Patuxent River, Md.

- Dec 2005 – June 2007, Commanding Officer, VX-23, Patuxent River, Md.

- Jun 2007- July 2009, Commanding Officer, Marine Aviation Detachment, Patuxent River, Md.

- October 2009 – present, Vice Commander, 33rd Fighter Wing, Eglin AFB, Fla.

FLIGHT INFORMATION

- Rating: Command Pilot Flight Hours: More than 3,200

- Aircraft Flown: T-34C, T-2C, TA-4, AV-8B, T-38, F-16, F/A-18A-F, VAAC Harrier, EA-6B, Lear 24, T-45, X-35A/B/C, Tornado GR1, F-4G, F-15, T-7, MIG-21, U-21F, P-3C, NU-1B, U-6A, AT-6, C-12A, DHC2, KC-130J, B-25, TH-6B, OH-58, Gazelle

AWARDS AND DECORATION

- Legion of Merit Defense Meritorious Service Medal with one oak leaf cluster Air Medal with numeral 3 and “V” device Meritorious Service Medal

- Navy Commendation Medal with Gold Star

- Navy Achievement Medal

EFFECTIVE DATES OF PROMOTION

- Second Lieutenant 13 June 1986

- First Lieutenant 7 April 1988 Captain 1 November 1990 Major 1 August 1996 Lieutenant Colonel 1 April 2002 Colonel 1 August 2007