Red Star Over the Pacific: China’s Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy, Second Edition

This book provides good insights into the Chinese regime and its approach to seapower as well as providing some solid thinking about how best to respond over the period ahead to this challenge.

The book also provides a very useful perspective with regard to how the Chinese approach seapower in a comprehensive way and provide an understanding of how the Chinese are leveraging several elements of seapower to augment their global position, rather than just focusing on the capital ships which China has built and is building.

The book by Toshi Yoshihara and James R. Holmes is not an easy book to read, in part because, it leverages original Chinese source material and using such material means that not only does one need to translate from a different language but from a different culture to explain how the Chinese are shaping their approach to seapower.

I did this with regard to the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s and there was always a challenge of going beyond the words to better understand the underlying concepts and approaches taken by the Soviet leadership and policy elite. The authors of this book face a similar challenge as well.

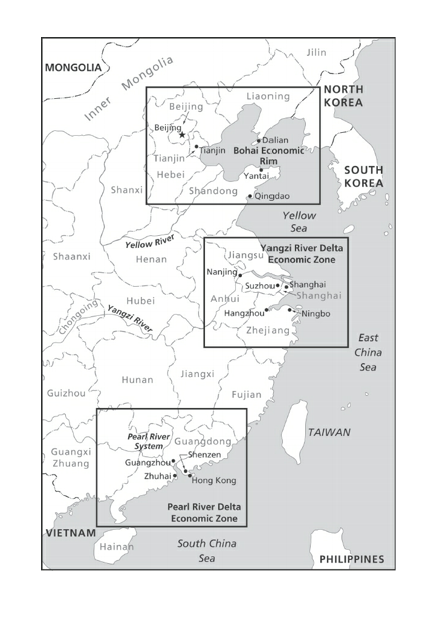

The core points can be put simply – China is no longer simply a continental land power but with the emergence of a significant engagement in the global economy, anchored by three key port zones, seapower is important.

But they also drive home the point that it is important to understand the evolving Chinese approach, rather than mirror imaging the US maritime strategy projected into Chinese technologies.

Beijing, in short, will compile its own script as it develops doctrine, tactics, and capabilities to meet its needs and conditions. The ensuing chapters examine in greater depth the sources, future direction, and strategic implications of the logic and grammar of Chinese sea power.1

At the heart of the Chinese transition with regard to seapower is the shift from benefiting from and leveraging the global liberal system which has been underwritten by the US Navy to shaping their own capabilities to defend their interests, operate globally and to provided extended defense of their crucial port regions, where significant population and economic capabilities are located.

The authors provide a good look at the core importance of the three port areas or systems in China which provide the core areas for the transit of goods into and out from China.

These port systems provide the core area which China wishes to defend and is doing so by building out from the mainland into the South China Sea.

The geography of Chinese production, distribution, and consumption has imposed new strategic demands on Beijing. China’s most important economic centers are now located along the northern, eastern, and southern shores.

The well-being of these megalopolises and the overall health of the Chinese economy depend on easy access to the maritime common that connects China to global markets.2

And as they are doing so they are using all of their maritime assets to do so, notably the Chinese Coast Guard, commercial shipping, fishing trawlers and other assets.

The authors highlight what one Chinese analyst has called the “cabbage strategy.”

Zhang Zhaozhong—a retired rear admiral, NDU professor, well-known television personality, and prolific author of nationalistic navalist books for popular consumption—explain(s) how a cabbage strategy works. The strategy, Zhang says, can be encapsulated in “just one word, which is squeezing.”

His explanation is worth quoting at length: “For every measure there is a countermeasure.…If you send fishing vessels to resupply, then we will use fishing vessels to keep them out; if your coast guard sends supplies, then we will send marine surveillance to keep them out. If your Philippine Navy ships hurry over, we will use naval vessels to keep them out. There is nothing to be afraid of, and we must stick it out to the end. The cabbage strategy of which I have spoken many times is to surround them layer by layer, and make them unable to enter [Second Thomas Shoal].48 (Our emphasis).”3

A key disconnect between Western navies and the Chinese over the past few years has been a clear focus by Western navies on maritime missions to support the global trade order whereas the Chinese have been focused on conflict at sea as well as global trade order missions.

China’s approach poses problems from a cultural standpoint as well. In the sense that “Mahanian” connotes girding for fleet battles and “post-Mahanian” means policing the sea or projecting power ashore, China is comfortable using post-Mahanian means for Mahanian ends.

A fishing trawler or coast guard cutter represents an implement of power politics as surely as a warplane or a hulking destroyer.

For their part, U.S. naval officers find it hard to deal with white-hulled China Coast Guard cutters or maritime enforcement vessels trying to cement command of Chinese-claimed waters. Countermeasures for maritime militia embedded within the fishing fleet and working in conjunction with law enforcement ships are still harder to come by.4

The authors note that this is changing as the US Navy begins to refocus on conflict at sea as a core mission and is modifying its combat assets to be more capable of so doing.

The authors conclude their book by looking at ways the US might more effectively counter the Chinese approach and to enhance core combat capabilities.

And it is China’s mounting resistance to the U.S.-led system of trade and commerce, which has nourished the regional order for more than seven decades, that makes the rise of Chinese sea power so worrisome.

Policy makers, then, must resist the temptation to focus narrowly on the material or operational dimensions of Chinese anti-access.

These are important beyond a doubt. But statesmen must recognize that China’s ascent and its accompanying dream pose an all-encompassing challenge to the United States and the long peace over which it has presided in Asia.5

I would add that a major aspect of working mid-term and long-term responses to the Chinese and to shape ways to constrain them is clearly how the US works with core Asian allies.

The military-technical aspects of so doing are important but so are the political-military as well as diplomatic.

But bluntly, how Japan, Australia, the South Koreans and others work together with the US in shaping the next phase of the liberal order is a crucial concomitant of the refocus on what the authors refer to as the “Mahanian” focus which connotes girding for fleet battles and “post-Mahanian or policing the sea or projecting power ashore.

The authors deal with the allied dimension in the context of how the Chinese see the general challenge facing them with regard to their core security challenges.

Geography colors how Chinese strategists appraise threats. The Korean half-island and the Japanese archipelago converge on key bodies of water while forming straits near China’s political and economic centers.

Whether the U.S.–Japan–South Korea alignment can ever become a coherent strategic unit is dubious at best in light of the two Asian allies’ turbulent past.

Nevertheless, Chinese observers find it unsettling that two U.S. allies boasting advanced economies and modern armed forces stand athwart sealanes essential to China’s security and economic health.

Sowing disunion among the allies would partly ameliorate this dilemma—and thus represents a strategic imperative for Beijing.6

Indeed, from my perspective working the technology and working the US and allied concepts of operations along with reshaping how the alliance will work in the presence of persistent Chinese efforts to change that Alliance is at the heart of the challenge.

For US policy makers, rebuilding the US Navy is a necessary but not sufficient condition; working more effective allied relationships to constrain and channel the Chinese is crucial as well.

Footnotes

- Yoshihara, Toshi. Red Star over the Pacific, Revised Edition (p. 47). Naval Institute Press. Kindle Edition.

- Yoshihara, Toshi. Red Star over the Pacific, Revised Edition (p. 65). Naval Institute Press. Kindle Edition.

- Yoshihara, Toshi. Red Star over the Pacific, Revised Edition (pp. 176-177). Naval Institute Press. Kindle Edition.

- Yoshihara, Toshi. Red Star over the Pacific, Revised Edition (pp. 142). Naval Institute Press. Kindle Edition.

- Yoshihara, Toshi. Red Star over the Pacific, Revised Edition (pp. 295-296). Naval Institute Press. Kindle Edition.

- Yoshihara, Toshi. Red Star over the Pacific, Revised Edition (p. 92). Naval Institute Press. Kindle Edition.