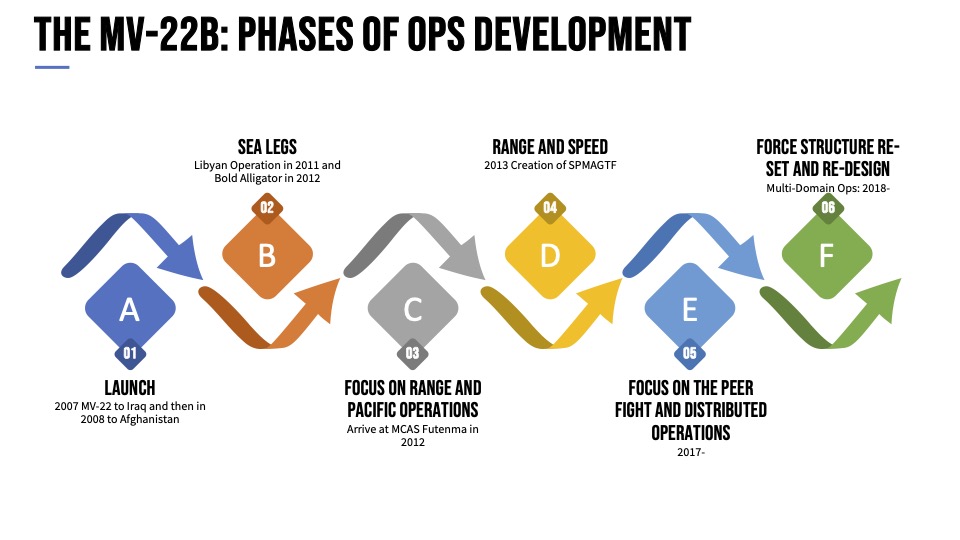

The Timeline for the Tiltrotor Enterprise: A Con-Ops Perspective (Part Two)

Focus on Range and Pacific Operations: 2012-

The MV-22B and the USMC would face a unique situation when the Obama Administrating announced their “shift to the Pacific” in 2011.

According to a 2012 Congressional Research Service Report: “In the fall of 2011, the Obama Administration issued a series of announcements indicating that the United States would be expanding and intensifying its already significant role in the Asia- Pacific, particularly in the southern part of the region.

“The fundamental goal underpinning the shift is to devote more effort to influencing the development of the Asia-Pacific’s norms and rules, particularly as China emerges as an ever-more influential regional power.”

Despite this announcement the priority was on the “good war” in Afghanistan, and the Administration did not put new resources and capabilities into the Pacific.

Rather, they had cancelled the F-22 program and put a hold on the F-35B program and had no upsurge in shipbuilding which would be needed for such a shift. The Osprey flew into the Pacific as they only new asset which presaged what would become what we face now a focus on the distributed operations strategic shift in the Pacific.

Put another way, the Osprey flew into history as the new platform shaping what would become a major strategic shift in the current period.

What the Osprey brought to the effort was a unique capability in terms of speed and range and landing flexibility to cover areas of interest for the U.S. military in terms of the insertion of force and of supplies. Fortunately, the aircraft had matured to its “self-deployment” capability and was able to go virtually anywhere with aerial refueling.

The Ospreys first arrived in the Pacific in 2012. Given the situation in Japan this was a complicated arrival, given Japanese concerns with the aircraft.

But through the years, confidence grew and the Japanese themselves would buy and operate the aircraft.

This article by Lance Cpl. Benjamin Pryer published on 23 July 2012 announced the Osprey’s arrival:

Twelve MV-22 Osprey tiltrotor aircraft were off-loaded from a civilian cargo ship at Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni, Japan, today. This marks the first deployment of the MV-22 to Japan. The aircraft will be stationed aboard Marine Corps Air Station Futenma in Okinawa, Japan, as part of Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 265 (HMM-265).

MCAS Iwakuni features both an airfield and a port facility, making it a safe and operationally feasible location to offload the aircraft. The offload was closely coordinated with Government of Japan.

“We are obviously pleased to demonstrate the capacity of this co-located deep water harbor and aerial port of operations. It clearly highlights Iwakuni’s position as a logistical lynchpin in the strategic alliance between the United States and Japan here in the Western Pacific,” said Col James C. Stewart, Commanding Officer of Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni.

Marines will prepare the aircraft for flight after its 5000-mile journey aboard the civilian cargo ship Green Ridge. However, the MV-22 Ospreys will not conduct functional check flights until the results of safety investigations are presented to the Government of Japan and the safety of flight operations is confirmed. Following safety confirmation and functional check flights, the Ospreys will fly to their new home aboard MCAS Futenma.

Groups opposed to the MV-22 deployment in Japan have demonstrated in Okinawa and Iwakuni. Recognizing the concerns of Japanese citizens led U.S. and Japanese officials to ensure safety of flight operations is confirmed before Ospreys fly in Japan.

Deployment of the MV-22 Osprey to Japan marks a significant step forward in modernization of Marine Corps aircraft here in support of the U.S. Japan Security Alliance. Throughout the Marine Corps, Ospreys have been replacing CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters, which made their Marine Corps debut during the Vietnam era.

The Osprey is a revolutionary and highly-capable aircraft with an excellent operational safety record. It combines the vertical capability of a helicopter with the speed and range of a fixed-wing aircraft. The Osprey’s capabilities will significantly strengthen the Marine Corps’ ability to provide for the defense of Japan, perform humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations and fulfill other Alliance roles.

The Osprey has assisted in humanitarian operations in Haiti, participated in the recovery of a downed U.S. pilot in Libya, supported combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and has conducted multiple Marine Expeditionary Unit deployments.

As of April 11, 2012, the Osprey has flown more than 115,000 flight hours, with approximately one third of the total hours flown during the last two years.

A second squadron of 12 aircraft is scheduled to arrive at MCAS Futenma during the summer of 2013.

The Marines were combining an operational shift which they called a “distributed laydown” which absolutely could not happen without the range and flexibility which the Osprey enabled. Its long legs supported by aerial refueling was new capability within a new strategic situation.

Let me put this bluntly: With the CH-46, the platform the Osprey was replacing, this was not going to happen.

In a 2014 article I outlined the strategic shift which the USMC was undergoing.

I had a chance to talk with the US Marine Corps, Pacific (MARFORPAC) in late February 2014 during a visit to Hawaii about their major project of reshaping and repositioning their forces in the Pacific over the next decade.

It is clear that a distributed laydown is a key element of shaping the deterrence in depth strategy in the Pacific and a fundamental tissue in building out an effective partnership strategy and capability in the region…

The distributed laydown started as a real estate move FROM Okinawa TO Guam but it clear that under the press of events and with the emergence of partnering opportunities the DL has become something quite different. It is about re-shaping and re-configuring the USMC presence within an overall strategy for the joint force and enabling coalition capabilities as well.

The distributed laydown fits the geography of the Pacific and the evolving partnership dynamics in the region. The Pacific is vast; with many nations and many islands. The expeditionary quality of the USMC – which is evolving under the impact of new aviation and amphibious capabilities – is an excellent fit for the island quality of the region.

The USMC is building out four major areas to operate FROM (Japan, Guam, Hawaii and, on a rotational basis, Australia.) But as one member of the MARFORPAC staff put it: “We go from our basic locations TO a partner or area to train. We are mandated by the Congress to train our forces, and in practical terms in the Pacific, this means we move within the region to do so. And we are not training other nation’s forces; we train WITH other nation’s forces to shape congruent capabilities.”

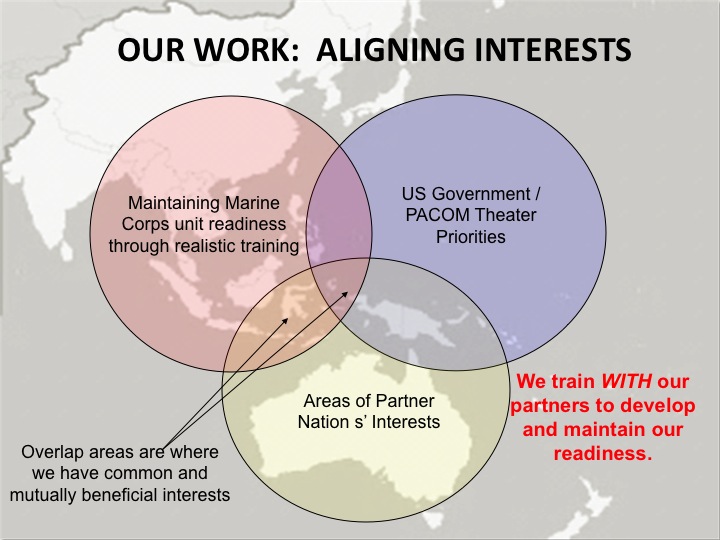

The basic template around which USMC training activities operate is at the intersection of three key dynamics: the required training for the USMC unit; meeting select PACOM Theater campaign priorities; and the partner nation’s focus or desires for the mutually training exercise or opportunity.

In effect, the training emerges from the sweet spot of the intersection of a Venn diagram of three cross cutting alignment of interests. This template remains the same throughout the DL but it is implemented differently as an ability to operate from multiple locations, which allows the Marines to broaden their opportunities and shape more meaningful partnership opportunities….

The Osprey is rapidly becoming a lynchpin for connecting the forces moving in the DL. It is also an intriguing platform for some players in the region who are thinking about its acquisition as well for it fits the geography and needs in the region so well.

And in a 2013 interview I did with MARFORPAC in Hawaii, he underscored this point with regard to the Osprey.

According to LtGen Robling: “Speed, range and presence are crucial to the kind of operations we participate in throughout the Pacific.

“The Osprey clearly fits perfectly into the types of missions we are tasked to perform.

“To illustrate hypothetically, if we were tasked to counter challenges in the South China sea, such as to bolster defense of Ayungin Shoal, also known internationally as Second Thomas Reef with one of treaty allies, the Philippines, the US has several options, but not all are efficient or even timely. We could use USAF assets, such as a B-2 bombers or B-52 aircraft from Guam, or Navy surface or subsurface assets that are patrolling in the South China Sea, but the location of those assets may not provide timely arrival on station.

“But using the Osprey, we can fly down quickly from Okinawa with a platoon of well-trained Marines or SOF forces, land on difficult terrain or shipping, and perform whatever tasked that may be required in not only a timely but efficient manner….

“I believe this because our allies and others look at what we can do with the Osprey and are impressed. We do not have the strategic lift required to move all my forces around the AOR. Until I can get them, I am required to use C-17s that are very expensive and committed elsewhere or amphibious shipping that there is not enough of, or I contract black bottom shipping, the cost of which as nearly triple in the last five years.

“To compensate, I can use KC-130 aircraft or V-22’s and move small numbers of lethal Marines thousands of miles. Is this efficient? No! Is this effective? Yes! Nobody else has the capability afforded by the V-22 except our USAF SOF forces.”

Range and Speed: The Creation of SP-MAGTF, 2013

The shift to the Pacific was one strategic impulse which leveraged the evolving capabilities of the Osprey. The 2012 Benghazi attack was another.

Terrorists attacked the United States diplomatic compound and adjoining CIA Annex in Benghazi, Libya, on September 11, 2012.

Despite repeated warnings from officials about the security risks in Tripoli and Benghazi, nothing had been done to prevent the attacks or to remove personnel.

Although we had seen something similar happen in Iran at the end of the Carter Administration, it was only the wake of the Benghazi attack that creating new capability built around the Osprey was a focus of attention. This would lead to the formation the SP-MAGTF.

In a 2013 article, I focused on the standup of the SP-MAGTF at 2nd Marine Air wing.

During this year’s visit to New River, a discussion with Major Frank “Robo” Rhobotham, VMM-364 Remain Behind Element (RBE) Officer in Charge (OIC), underscored how significant the Osprey has been in forcing culture change in the USMC and shaping new combat approaches.

In the discussion with Rhobotham, two key aspects of change were discussed. The first involved the standpoint of the Special Purpose MAGTF, now in Spain, and the second the changing approaches associated with a younger generation of maintainers, who work on the Osprey.

Rhobotham discussed the very short period from the generation of the concept of the Special Purpose MAGTF to its execution. It took about eight months from inception to deployment.

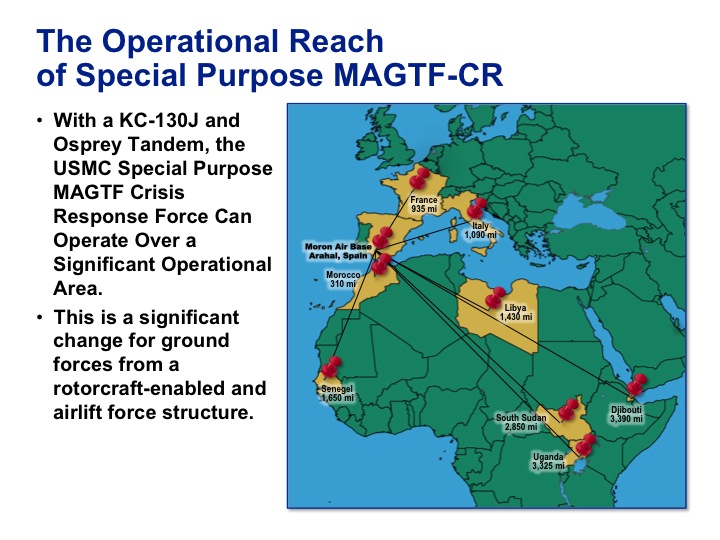

He emphasized the flexibility of the force and its light footprint. “With a six-ship Osprey force supported by three C-130s we can move it as needed. The three C-130s are carrying all the support equipment to operate the force as well.”

“The flexibility, which the Osprey now offers Combatant Commanders and US defense officials, is a major strategic and tactical tool for the kind of global reality the US now faces, requiring rapid support and insertion of force.

Question: Could you describe the process as seen from your end?

Major Rhobotham: “We received a request to look at the deployment of a 6-ship detachment of Ospreys to operate flexibly as a group. That started a long, long conversation because it depends on what you want to do with those six airplanes.

“Are we going austere, are we working from a prepared zone; are we going to fly 100 hours a month, or are we going to fly 500 hours a month? And where are we going to operate it for environment matters to the performance and endurance of the aircraft?

“It is similar to thinking about ground transportation and what car you would use.,Take the Baja 500, for example. If you buy a truck from the Ford dealership, and you drive it around LA, you’re going to get 150,000 miles out of it. You take that same truck and you attempt to run the Baja 500, you won’t make it past the first day.

“It is the same thing with this aircraft. If I go from paved runway to paved runway and I fly in airplane mode the entire way, I’m going to get a lot more use out of it. And if I’m flying it like a helicopter and I’m landing in nasty, dusty, dirty environments, it’s going to break down, as any mechanical device will do in that environment.

“Additional questions had to be answered. Where are we going? What are we going to do, how much are we going to fly? Who are we supporting, how are we being supported?

“We then got a response back that Africom was interested in what a six-plane V-22 force would look like. With the Africom focus that shrunk the bubble down. The continent of Africa has about every single environment out there.

“Mali happens in the middle of this. While we were not told that Mali was even in the play, it was dominating the news in the time period that we began the planning. We really started looking at the western coast of Northern Africa, we looked at the Northern portion of Africa, and obviously Libya is all fresh in everybody’s memory.

“We’re an assault support unit; we are always supporting, and we’re supporting the Marines. So obviously, we, by ourselves, are not a force. We enable somebody else to be a more efficient, more effective force.

“And that also helps as well in thinking about the deployment focus.

“What can we do with the company, how can we help a company? And we fell back upon our MEU mission sets. If we’re going to be supporting the African countries with a company, we draw upon what we know.

“We were given some restraints to the diplomatic clearances with our European partners, which shaped the force to a certain degree. And then there’s always the what-ifs.

“As a result, we deployed out relatively heavy. We’re running two ships of maintenance in the field, and we have round the clock maintenance.”

Comment: Obviously the light footprint of the force gives it significant operational flexibility.

Major Rhobotham: “That is a significant benefit. If for some reason, due to political turmoil in any of those countries, it doesn’t take much to completely pack up and move.

“And it helps that the Osprey has a refueling probe. We’re no longer limited to how far the ship is willing to steam in one day. Now we’re limited to how much can that tanker hold?

“And we can put the Marines in the back and tank, and as long as I’ve got a C-130 that’s willing to go with me and has something to give me, it’s human limited now. How many hours can I fly this airplane before I’m too fatigued?

Question: The Marines deployed the SP MAGTF in April?

Major Rhobotham: “It was deployed in April and it actually self-deployed. The V-22s flew across the Atlantic, and although it has been done before, this is a new operational reality which folks need to recognize exists. We got all the airplanes where they needed to go flying there, and not being airlifted by the USAF.”

Question: In your view how is the SP-MAGTF different from a MEU?

Major Rhobotham: “It compliments a MEU very, very well. It is a different tool set. It is similar to having both a screwdriver and you’ve got a drill in your toolbox; that drill is a lot like the MEU. It’s a lot more powerful, it can go a lot faster; it can do a little bit more powerful things. But it doesn’t mean you need to throw away your screwdriver.

“The SP-MAGTF has a lighter footprint, and we can go to any place that the government sees that needs a little bit of attention; we can drop one of these special purpose MGTFs off.

“We can just go wherever we need to, drop it off, and then when that situation’s resolved itself or reached some sort of threshold that we feel comfortable, we can pick this up and move it anywhere we want to.

“In the past we would have to fly in infrastructure or move by ship; establish the infrastructure and the diplomatic agreements to place the infrastructure in country. Now I can fly in the force; stay until I wish or need to depart.

“A special purpose MGTF is not to replace a MEU; it is to compliment a MEU. And while there are separate commands, they’re not led by the same colonel, they’re designed to complement each other, not to replace each other or be lieu of each other. And I think that’s probably a point that doesn’t get made enough.”

Featured Photo: An MV-22B Osprey with Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force Crisis Response, prepares to conduct nighttime tiltrotor air-to-air refueling with a KC-130J Hercules over the southern coast of Spain, Aug. 22, 2013. U.S Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Michael Petersheim.

We have published a book in 2023 which looks specifically at the role of the Osprey in the shift to the Pacific.

We have also published a 2023 book on the Obama Administration and its foreign and defense policies.