Communication Disruption Attacks in a Nuclear Context

The spread of nuclear weapons to second-tier countries (North Korea, Pakistan, Israel), and the modernization of nuclear postures of major powers (Russia, China, India, United States) creates a nuclear context for international relations. This context is increasingly salient in many areas– yet it often goes unacknowledged. For example, it is increasingly relevant in a wide range of conflicts, from crises and conventional war to blackmail, coercion, and risk taking.

Yet the contours of this world — this second nuclear age — are often overlooked. This is because not analyzing what a nuclear context means, is, so to speak, a way of hanging onto a past that was largely free of it. It is feared, often with good reason, that exploring this nuclear context could accelerate our movement into it. Studying it could be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But a case can be made that not analyzing these issues carries its own risks. It could lead to a blundering into situations that were otherwise preventable if we had thought through what we were doing. Or it could lead to overlooking major vulnerabilities or risks simply because they were associated with what are seen as a highly undesirable development, namely, that nuclear weapons actually matter.

The current article analyzes the importance of communications in this nuclear context. It recommends that we ought to distinguish between attacks designed to maximize disruption of communications, and attacks which happen to disrupt them as a collateral effect.

The idea is that in a nuclear context we should evaluate disruption to enemy communications similar to the way we analyze civilian collateral damage. Sometimes it’s acceptable to have high levels of civilian damage when there are other important objectives.

Broadly speaking, however, in a nuclear world we should be very careful about attacking enemy communications.

However, the least desirable situation is to not be clear in our own minds about what we are doing.

I think this is where we are now.

Some attacks are intended to disrupt enemy communications. Other kinds of attack are aimed at weapons, but spill over into disrupting communications.

Why is it important to distinguish between these two kinds of attack?

The answer is straightforward.

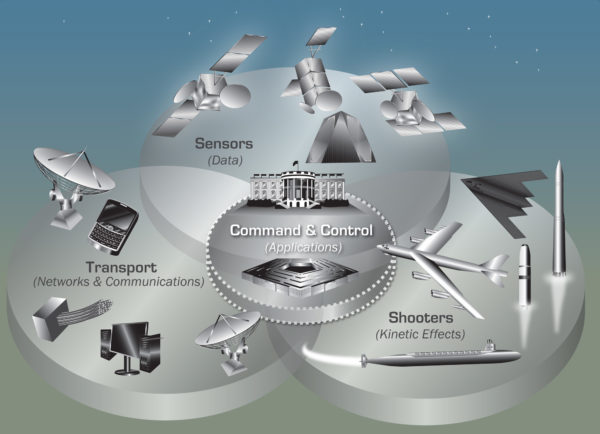

It’s that communications is one of the three building blocks of any deterrent strategy.

These are capability, communications, and credibility, the three C’s of deterrence. Two of these, capability and credibility receive a large amount of attention. Today, virtually all of the nuclear weapon states are putting resources into increasing nuclear capability. This includes the United States, China, Russia, and India. It also includes Pakistan, North Korea, and very likely Israel. They are either building more weapons, or developing new ones.

There is also a reassessment of nuclear credibility in academic and think tank circles. Tailored deterrence and conventional counterforce have been advanced as a way to strengthen it.

Communications is an outlier in this respect.

It is both a darling and the stepchild of deterrence. It is a darling because there’s wide agreement that a country needs to communicate red lines that might trigger nuclear use. But it is a stepchild because almost all analyses overlook the implications of what is clear to military planners: the biggest vulnerability in a nuclear posture is communications. This makes it a prime target, but one which at a strategic level no one admits to openly.

We are in a situation where the military fully expects to attack enemy communications and develops plans accordingly. Yet these plans do not account for the consequences of such attacks on further escalation.

Some Examples

There are many examples of disruptive communication attacks, and also of collateral communication damage attacks. Some cases are planned or hypothetical, played in war games or tested in scenarios. In the Cold War attack on communications was a worst case example of nuclear attack. There was serious worry over a nuclear attack on Washington DC, the AT&T telephone network, the power grid, and command and control centers. EMP attack, ASAT, and electronic warfare were also part of these plans.

The idea of attacking communications, along with missiles, bombers, and submarines in port was to make the United States retaliate with a damaged force that would be far from the full weight of attack of an undamaged one.

An attack on U.S. communications would lead to ragged retaliation that was likely less devastating than with an undamaged force.

Many war games and Strategic Air Command studies began with an opening Soviet nuclear salvo against Washington, and with EMP bursts over Nebraska in order to knock out the U.S. power and telephone networks.

In the 1980s, however, it became clear that the U.S. communications system — not the weapons — was the weak link in the nuclear posture.

Buying more weapons served little purpose for bolstering deterrence if communications vulnerabilities could paralyze the retaliatory blow. A great deal of effort was put into hardening the U.S. system, and to clarify authority lines in a chaotic environment. These responses were especially important because they more clearly defined command and control of retaliation. They included predelegation of launch authority, line of succession in the command system, and very importantly, the timing and procedures for determining who was alive and capable of taking charge of the military under catastrophic circumstances.

Let’s consider the other end of the spectrum, attacks which cause disruption as a collateral, unanticipated, or unknown consequence of an attack aimed at other targets.

On 9/11 the attack on the World Trade Center and Pentagon illustrated how the U.S. communication system broke down. These attacks were intended to destroy visible symbols of American power, the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. They were not designed to disrupt U.S. communications.

Yet they had this effect. One of the points I would like to underscore here, is that a “tiny,” non-nuclear attack on the United States caused a serious breakdown in communications that delayed timely action, distorted the military’s understanding of what was taking place, and endangered national leaders.

Some examples of this breakdown are worth highlighting.

One was the initial Air Threat Conference Call initiated by the National Military Command Center (NMCC) in the Pentagon after the attack on the World Trade Center Towers, but before the attack on the Pentagon.

NORAD (the North American Aerospace Defense Command in Colorado Springs) asked three times for inclusion of an FAA representative (Federal Aviation Administration) in the conference call with the NMCC. NORAD’s first request for this was at 10:03 am. It was only at 10:17 am that an FAA representative did join the call.

But this person knew nothing about emergency response procedures, either of the FAA or the NMCC. He had no access or communications to other FAA officials who might have such knowledge1

In the context of the crisis on 9/11 these fourteen minutes had little bearing on the outcome of that dreadful day. But fourteen minutes, or longer if we recognize that the individual joining the call on behalf of the FAA had virtually no useful knowledge or authority, is a long time. In the nuclear world of hypersonic and ballistic missiles it is an enormously long time, long enough to destroy an enemy force on the ground if other factors are brought into consideration.

A second communications breakdown during 9/11 was the continuity of government plan for protecting U.S. leadership and ensuring that it had control over the military.

This plan utterly failed to be implemented because the officials involved either didn’t know what it was, or declined to follow their assignments in the chaos of the situation. The protection plan for U.S. leaders on 9/11 collided with a long planned nuclear war game. This game called for uploading live warheads onto B-52 bombers at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, among other places. This happened to be the base chosen to refuel Air Force One after its emergency evacuation of the president from Florida.

As a response to 9/11 the military wanted to raise the U.S. alert level. But to do this they needed to secure the bombs used in the exercise, and this created a lot of unplanned issues. I do not know whether on 9/11 Russian intelligence picked up the coincidental and unrelated activities of the nuclear war game.

But this seems likely knowing how these things work. The Russians have long used spotters at U.S. bases to look for changes in operating levels. They would not know, of course, that events at Barksdale on that day were driven by two developments, the war game and the 9/11 attacks.

In short, the President was not in touch with U.S. forces because he couldn’t communicate with them. More fundamentally however, no one could have anticipated the contingency that developed.

This had the military out of position on multiple fronts: they were moving live weapons around in an exercise when the 9/11 attack took place; had to handle an emergency visit from the president at an important nuclear base; couldn’t connect the president with Pentagon while airborne; and had radars aimed at a threat “outside” rather than inside of U.S. air space.

A more detailed description would show how the U.S. military was caught off balance that day, and how communications to right the system couldn’t be established. Everyone was in the dark, reaching out for information that wasn’t available because the organizations involved weren’t designed for this kind of contingency.

What turned out to be a “small” attack by the standards of war, conventional or nuclear, caused a serious disruption to U.S. communications.

Discussion of the Examples

The lesson I take from these examples is that no complex system can perform well under conditions it doesn’t anticipate happening.

It’s all well and good to talk about flexibility and agility.

But there are serious limits to what can be accomplished with them.

It takes repeatable experience, drill, learning, and practice.

No one can possibly anticipate all of the developments that one discovers in actual operations. Think of the U.S. Army in World War II. In the assault on North Africa it saw one disaster after another. It greatly improved during the invasion of Italy. And in France in 1944 it was one of the most impressive fighting organizations in history.

The lesson I take from these examples is that software improvements, “storm testing,” fault trees, blockchain, system hardening, etc. are less important for performance than drill, experience, and learning from the realistic practice of operations.

I think 9/11 showed this clearly. A small unanticipated attack paralyzed elements of the command system. The attack wasn’t intended to do this, yet it did.

The heart of the problem is that there is nothing like real experience to work out the bugs in a complex system. But with nuclear forces you can’t really get experience of what a war would be like in peacetime.

So what are the options?

What should we do?

The answer, I suggest, is either to “change worlds,” or to do the best we can in the world we are given. By “changing worlds” I refer to things like nuclear abolition and global zero — i.e. eliminate nuclear weapons altogether.

Or drive them into the deep back background so that they are irrelevant except in certain unimaginable circumstances, like a Russian surprise attack on the United States.

In other words, remove them from the context of international relations by placing them into an extremely narrow and remote category of relevance.

I argued, however, in the introduction to this article that this was getting much more difficult, because the context of international relations was taking on more of a nuclear character.

So another alternative is to do the best we can in this world, the one we see developing.

Here, there are grounds for some optimism. That is, we can raise the level of debate about managing in this nuclear world.

One way to do better is to make the distinction in plans, on whether enemy communications is a high priority target, or whether it may merely receive collateral damage from attacks on other targets.

Are We on a New Learning Curve?

A fundamental question needs to be asked about the developing nuclear context. It’s a question with special relevance to communications.

The usual question that is asked in the U.S. security debate focuses on command and control. It can be put as “How can we field a safe, reliable, effective command and control system, one that fits the nuclear weapon modernization now taking place?”

It’s interesting that when put this way nearly everyone thinks that it’s a good question. Nearly everyone, that is, supports a “safe” system. This is meant to convey that it won’t launch by itself, i.e. there is strong protection against accidental firing of weapons. Likewise, everyone supports reliability. This means that the system can’t be knocked out, either by nuclear attack or by other means like cyber, EMP, or ASAT. By “effective” people mean that the system is credible. It looks “serious” enough to do the job, which is deterrence.

That everyone thinks that this is the right question (“build a safe, reliable, effective command and control system”) is itself a noteworthy change.

For one thing, it shows how the security debate has shifted from its focus of the 2009 era. The question then was “How do we get rid of nuclear weapons?” A variant was “How do we get to ‘global zero’ nuclear weapons with some coordinated build down of these things.”

In either formulation there was no need to think about command and control and how it fit in to deterrence.

But there’s a different question that needs to be asked, one that follows from the nuclear context now covering more and more levels of international security.

As nuclear weapons spread to more countries, and as advanced technologies (cyber, AI, drones, hypersonics) spill into the nuclear competition, are we facing a new learning curve?

This happened before, in the Cold War.

In the 1950s both the United States and the Soviet Union began to climb a twenty-year learning curve of nuclear interactions. A learning curve describes the rate of learning about something over time or from repeated experience. No long term rivalry with nuclear weapons had ever taken place before. So there was no experience to draw on. It was all “new.”

What did nuclear weapons mean for conventional forces, escalation, plans, command and control?

No one really knew so they had to do the best they could with studies, war games, and scenarios. And one more source of data: real world experience. This learning curve was greatly shaped by serial crises: Taiwan, Berlin, Cuba, Lebanon, U-2s over Russia. These crises exposed big gaps, just as 9/11 exposed big gaps in 2001.

In the 1962 Cuban crisis, for example, it was extremely difficult to reach Moscow in a timely way. And it was impossible to reach allies in Latin America because the telephone system simply couldn’t handle it.

Yet over a twenty-year period the two sides developed a complicated system of nuclear interactions.

Don’t go on provocative exercises in several geographic regions at the same time.

Avoid high alerts. Make sure the political leadership reviewed dangerous nuclear missions.

Don’t depend on one source of warning information, but build your intelligence around multiple streams of data, like radar, infrared, communications intelligence, etc.

The United States and the Soviet Union still competed against each other. But they adjusted their behavior to the nuclear environment they were in. It was a real, honest to god learning curve. It prevented the competition from becoming intolerably dangerous.

Today there are multiple decision-making centers when it comes to nuclear weapons, not just two. We need to consider the interactions of countries even if the United States is not directly involved.

India and Pakistan come to mind here.

And the technologies are very different now as well. In addition, there’s increasing overlap between the command and control of conventional with nuclear forces. This arises from growing dependence on sensors, satellites, cyber, and AI in the military enterprise.

So the environment of the early Cold War is different from today on a number of levels.

But there’s still an important role for learning about this new context.

The learning curve question, for today, can be put as follows.

Are we facing a new learning curve of nuclear interactions, now for multiple powers?

And a closely related question: might this offer a way to gain experience about adjusting behavior to fit this environment?

This is a very different question than how to build a “safe, reliable, effective command and control system for nuclear forces.”

It requires a deliberative response. Jumping automatically to an answer is bad policy analysis.

What might an answer to our question look like?

Let’s put together a list of possible answers to it.

I do this here in a reverse order of antagonism.

That is, the options listed at the top have a low degree of enmity, risk, and animosity.

Those below have more of these traits.

(1) We must not view the question of a new learning curve as the important one. Rather, we should do everything possible to climb an altogether different learning curve, one that moves us toward disarmament or making nuclear weapons irrelevant in international affairs. We should confine nuclear weapons to certain highly unlikely and largely unimaginable possibilities, like a large Russian or Chinese nuclear surprise attack on the United States.

(2) As long as the United States possesses the capacity to strike back with a massive counter blow after absorbing a large attack there really is no learning curve. Another way of saying this is to assert that the new (and old) learning curve is a step function. It says that you either have a second strike capability or you don’t. If you do, that’s all you need and no further analysis is needed. In fact, any such thinking might be dangerous.

(3) Double down on drills and practice under the new conditions of cyber attack on the nuclear forces, missile threats from second tier countries like North Korea and Iran, and their attacks on supporting systems like communications, space assets, and electric power.

I would argue that the United States has moved in this direction over the last five years. Regardless, this response recognizes that there are new threats, that the strategic environment has changed, and that military plans and exercises should take account of the change.

These new conditions are technological and political. So far, most action in this regard has been to recognize the technological changes and threats, not the political ones. That is, there is more recognition of cyber threats to U.S. nuclear forces, ASAT, EMP, etc.

However, there is little realistic political play in this space. The political action is “wooden,” and highly scripted.

(4) A nuclear context will shape future crises between the United States and other countries.

By this I mean not just the recognition that nuclear weapons exist, but that they will come to the foreground once a serious crisis develops between nuclear armed states. In peacetime the nuclear context is dismissed.

But in a crisis or coercive situation of some kind it will quickly move to center stage. The vast damage inherent in these weapons means that the middle and upper rungs of the escalation ladder are blocked off from feasible action.

The focus will shift to lower rungs of escalation, things like moving nuclear weapons around, going on alert, preparing forces to fire.

The intent is what I call a “nuclear head game.”

It’s political signaling, but with a broad unspecific message: “this crisis could get out of control as neither one of us understands our own forces

Let me reemphasize that I am not arguing for any one of the above answers. Different actors in the security debate will advocate policies that fit their view.

But the list does raise one obvious question.

If the purpose of “safe, reliable, effective command and control” is to get off a retaliatory blow then the problem is greatly simplified. We can do this with high probability of success I would argue.

Yet “getting off the retaliatory blow” may not match the world we are moving into. The last two responses come closer to this world. And if we prepare for a world where only getting off the retaliatory blow is what matters, we may invite nuclear threats and head games at lower levels of crisis.

These could be extremely effective in paralyzing any U.S. military response, including those cases where it was needed.

It could, for example, offset U.S. conventional military strength.

A Policy Recommendation

One recommendation follows from this discussion.

It is that the United States should distinguish between attacks whose intent is to destroy enemy communications outright, and those which do so incidentally to attacks undertaken for other purposes.

The reason for the recommendation is because current trends in technology and plans are mixing up conventional and nuclear forces.

They both use the same systems. For example, missile warning systems are used by both. In addition, communications is so clearly the weak link in the three C’s deterrence framework (capability, communications, credibility) that it stands out as a leading target.

Someone might argue that there is always going to be damage to enemy communications in war, and that this cannot be precluded, and that therefore my recommendation is impractical. But this view is exactly why we need the distinction.

My concern is that we’re using advanced technology (cyber, hypersonic missiles, etc.) to disrupt enemy communications without thinking it through.

And it is not clear to me that civilian leaders understand this. They might, for example, approve “conventional” attacks which are not really conventional at all in their consequences.

I am not proposing a “no attack” policy on enemy communications. It’s more like the evolution of attitudes about collateral damage. Fifty years ago the belief was that there is always going to be civilians killed in war. Putting restraints on operations to exclude civilian proximate targets would never work, and interfered with professional military judgment.

No one in the United States says this any longer. It didn’t mean that no civilians are killed. But the shift to making collateral damage a basic distinction in planning brought it to the foreground of attention. It made it clear that collateral damage was something that had to be briefed to civilian leaders.

It made it unacceptable to treat collateral damage as something ambiguous, that might be included in a briefing or not, depending on the circumstances.

In a nuclear context, attack against the enemy’s communications is no less important.

This paper is based on an earlier paper written for a conference on nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3), and was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The graphic is taken from various US Nuclear Command, Control, and Communication (NC3) Systems, as of 2016.

From Nuclear Matters Handbook (2016).

For Dr. Bracken’s bio, see the following:

https://politicalscience.yale.edu/people/paul-bracken