The Brazilian Amazon and Globalization

The UN climate action summit in New York City was held on Monday 23rd September.

Two days earlier, beginning in Melbourne, Australia, four million young people in 150 countries, were on the streets in cities and towns throughout the world in peaceful climate change demonstrations (apart from Paris where the “yellow vests” hijacked the protests and turned the demonstrations on the fringes into violent confrontations with the riot police.)

The global climate demonstrations were inspired in large part by Greta Thunberg, the Swedish climate activist. Only a year before, on 20th August 2018, she sat down outside the Swedish Parliament to begin a lonely weekly Friday school strike to protest climate change.

The UN meeting came after the G-7 summit in Biarritz, France, where the host, President Emanuel Macron, had spearheaded the charge against President Jair Bolsonaro, joining forces with Ireland, in threatening to block a trade deal between the EU and the South American counties of Mercosur (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay) unless Brazil took action to stop vast areas of the Amazonian rain forest from burning.

Bolsonaro accused Macron of having a “colonialist mentality.”

Macron tweeted: “Our House is burning. Literally. The Amazon rain forest – the lungs which produce 20% of our planets oxygen is on fire.”

Macron accused Bolsonaro of having “lied” at the G-20 summit in Osaka, Japan, earlier in the year, about his commitment to fighting climate change.

The war of words between Macron and Bolsonaro escalated when Bolsonaro compared Brigitte Macron (66) unfavourably to his own 37 year old wife third wife. It was a typical Bolsonaro machista comment.

Predicably it provoked a twitter firestorm in both Brazil and in France.

Ironically it was in Brazil, and in Rio de Janeiro no less, that in 1992, Severn Cullis-Suzuki, from Vancouver, Canada, a member of a group of 12 to 13 year-old children, spoke up eloquently at the UN conference on the environment and development about the dangers of climate change.

In 1992 the internet had not yet provided the means for an individual young person to reach the world.

In 2019 it does.

President Donald J. Trump, who had not attended the climate change session in Biarritz, dropped by briefly at the climate summit at the UN on his way to the White House sponsored summit on “religious freedom.”

He missed Greta Thunberg’s angry denunciation of the assembled delegates.

“How dare you” she said. “you have stolen my childhood.”

Trump tweeted later that “she seems like a very happy young girl looking forward to a bright and wonderful future. So nice to see.”

The 16 year-old Swedish activist was later filmed staring icily at the 73 year old American President as he passed by in the UN lobby.

The Brazilian President, Jair Messias Bolsonaro, like Donald Trump, is a climate change denier.

Bolsonaro also had his time in the UN limelight.

He gave the opening address before the General Assembly.

Brazil has performed this role since 1955, although the first Brazilian President to give the opening address was the military regime’s President General João Figueiredo in 1982.

Bolsonaro did not disappoint.

In his address, he upheld Brazil’s ”sovereignty” over the Amazon and criticized the ”sensationalist” reports on the burning of the Amazon rain forest.

He claimed that he had saved Brazil from “socialism” and attacked the “Foro de São Paulo” (a forum of left wing Latin American parties which had once included Brazil’s Lula, Cuba’s Castro, and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, among others) which is a recurrent bugbear of the Brazilian right.

He condemned the 10,000 doctors Cuba had sent to Brazil under his Worker’s Party (PT) predecessors. He described the Cuban doctors as being “slave” labor.

Bolsonaro went on to say that Brazil was combating the corruption of the past and praised the actions of the former judge Sérgio Moro, now his justice minister.

He attacked Venezuela, eulogised Trump, attacked the media, and said that the indigenous reserves in the Amazon needed to be able to exploit the resources within (and under) their territories.

He attacked the cacique Raoni Metuktire of the Kayapo, a world famous Brazilian indigenous leader and environmentalist.

He said Brazil was open to the market economy.

The speech was an undiluted expression of Bolsonaro’s core values and was a victory for the anti-globalists, as well as for the Brazilian military within his administration, who view the international NGO’s as agents of foreign powers avaricious for access to Brazil’s natural resources.

The climate crisis has become a major global clash of perceptions pitting two types of globalisation against one another.

On one side are the young activists demanding action, bolstered by some scientific opinion and academic experts (and supported by Prince Harry among others), who all warn that the world faces an imminent catastrophe, and that action is urgently needed to curb green house gases and carbon emissions.

The UN’s world meteorological organization issued a stark report on the eve of the UN climate summit.

The report pointed out the gap between agreed targets (as exemplified by the Paris climate accords) to tackle global warming and actual reality. Average temperatures over the period 2015-2019 have been the warmest for any equivalent period on record with long lasting heatwaves and record breaking fires.

Changes in land use and energy must be made “in order to avoid dangerous global temperature increases with potentially irreversible impact.”

Greta Thunberg put it more graphically in her furious speech: “All you talk about is fairy tales of eternal economic growth.“

In the western world the ”nationalistic” forces led by Trump, with Bolsonaro very much in the forefront, form an anti-scientific brigade.

Trump and Bolsonaro both attack the role of experts.

Both deny the scientific claims being made by a number of climate change analysts.

Brazil has become the center of this conflict and the Amazon the crisis point.

Ironically, although the principle personalities have changed, the dispute is a very long standing one.

The “burning of Brazil” has galvanised international attention, as well as activists, at least since the 1980s, and the vast Amazon Basin has been at the core of international concern.

Bolsonaro’s attack at the UN on Raoni Metuktire could not have been more revealing.

The 87 year-old Raoni has long been a star on the international environmental scene and is talked of as being a candidate for the 2020 Nobel peace prize.

He has been particularly popular in France where he was made an honorary citizen of Paris in September 2011.

He is chief of the Kayabo people from the savanna lands of Mato Grosso and the savanna/rain forest lands in Pará along the Xingu river and it’s tributaries.

He was first sponsored by the Brazilian anthropologist Orlando Villas Boas in 1954. Raoni is famous for his lip plate under his lower lip and yellow feather headless.

He came to international attention in 1973 in a documentary made by Jean-Pierre Dutilleux which was exhibited at the Cannes film festival in 1977, and was nominated for an Oscar in 1979. In 1989 his cause was taken by the British rock star Sting and his Rainforest Foundation.

Raoni was successful in the establishment of a large protected indigenous territory in 1961.

This effort was supported by international tropical forest protection organisations, NGO’s, and foreign governments, principally Norway. The area was reduced in 2001 as agricultural frontier expanded in the area.

The key issue for Raoni became the great Belo Monte hydroelectric dam project in the northern part of the Xingu River in Para, which will be the third largest hydroelectric dam in the world.

This is a project the Kayapó have been opposing since the 1980s since it threatens the survival of the indigenous communities that depend on the river for their survival.

The Belo Monte dam was a project much promoted by the very “socialist” PT governments that Bolsonaro condemns so vociferously.

Dilma Rousseff, the ousted PT president, was the Brazilian minister of mines and energy in the first Lula PT administration, and her actions led to the alienation of Marina Silva, the minister for the environment, and to her decision to break with Lula.

Marina Silva, who grew up in Acre and was illiterate until her late teens, was a close associate of the murdered Amazonian rain forest rubber tapper and environmental activist Chico Mendes who was a founding member of the PT. Marina Silva remains a leading Brazilian politician and defender of the environment.

Bolsonaro and his close advisers are all virulently anti-globalist. He condemns President Macron and his fellow G-7 leaders for wanting to retain the Brazilian indigenous communities as “cavemen.”

Bolsonaro is very much part of the new “internacionale” of right wing political leaders, many encouraged by Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief strategist, Steve Bannon is a close friend of Jair Bolsonaro’s son, Eduardo Bolsonaro (PSL São Paulo), who he has encouraged to establish an international South American equivalent to the “Foro de São Paulo”, by espousing and promoting an international nationalistic right wing philosophy.

Brazilian Foreign Minister(Chancellor) Ernesto Araújo, has declared that Brazil under Bolsonaro has a chance to recover its “western soul.” He claims that climate science is “dogma” and part of a plot by “cultural Marxists” to stifle western economies and promote the growth of China. He attacks the “criminalisation” of red meat, oil, air conditioners, Disney moveis, and heterosexual sex.

”Globalisation” he asserts is a “a type of religious atheism where religion together with environmentalism is all of product of “Gramscism” (named after the Italian neo-Marxist and communist philosopher. Antonio Gramsci.) Filipe Martins, Bolsonaro’s chief foreign policy adviser in the Planalto (the Brazilian presidential palace in Brasília ) is even more explicit: He claims that globalisation is an ideology of a technocratic cosmopolitan elites within multilateral organisations that wish to destroy national sovereignty.

With Trump and Bolsonaro none of this should be surprise.

Each has a very long career of promoting conspiracy theories and attacks on “experts.”

Bolsonaro spent over two decades in the Brazilian Congress railing against women, gays, indigenous peoples and their supposed special protection.

Trump had spent almost fifty years attacking his perceived enemies and competitors, advised for many years by his original and perennial attack dog lawyer, Roy Cohn, who honed his skills working for senator Joe McCarthy and New York City Mafia crime bosses.

Bolsonaro brought his own “Indian”, Yasani Kalapola, to the UN with him. She claims the Amazon fires are “fake news.”

Bolsonaro in an interview with the Brasília based newspaper “Correio Brasiliense” claimed in New York that the “Indians want to be integrated into society, they want to grow, mine, exploit tourism in their lands.” He said that Raoni was a “Bon vivant” who ”speaks French and no longer speaks his own language and lives travelling the world.”

His son, Eduardo Bolsonaro (PSL-SP), who he has nominated to be the Brazilian Ambassador in Washington D.C., (with Trump’s enthusiastic support), and who accompanied his father to New York (as he did to the White House with his father on a previous visit to the US), was photographed at the UN standing before the UN peace statue imitating his father’s favourite gun gesture.

Eduardo Bolsonaro, once famously said during his campaign to be a federal deputy from São Paulo, that it would only take a “cabo e dos soldados” (“a corporal and two soldiers”) to shut down the Brazilian Supreme Court.

Since then Eduardo Bolsonaro has become a “friend” of Antonio Dias Toffoli, the head of the Supreme Court. Justice Toffoli subsequently quashed an investigation into Flávio Bolsonaro, another Jair bolsonaro son and a congressman from Rio de Janeiro, for alleged misuse of government funds and money laundering.

Flávio Bolsonaro allegedly has close connections to the “milícias”, that is the groups of off duty police officers who form violent extortion rings in the Rio favelas, controlling taxes, property, transport, arms trafficking, cooking gas supplies, all estImated to be worth US$100 million a year in Rio de Janeiro along, and occupying the space effectively abandoned by the state. Jair Bolsonaro famously said “a good bandit is a dead bandit.”

One of his priorities as the President of Brazil has been to facilitate gun ownership. The gun lobby in the Congress is among his most ardent supporters.

Like Trump and his attacks on the environmental protection agency, Bolsonaro has cut back funds to federal universities in Brazil.

His minister of education, Abraham Weintraub, Is one of the most ideologically driven members of his administration. Bolsonaro fired Ricardo Galvao, the respected MIT trained physicist, who headed the Brazilian National Space Research Institute (INPE) in the midst of controversy over its satellite data showing a rise in Amazon deforestation. Ricardo Galvao reported that sharply rising deforestation was undeniable and that there had been a 88% rise in deforestation in June compared with the same period a year before.

The US Space Agency has said that overall fire activity in the Amazon was slightly below average this year, though fire activity increased in the Brazilian States of Amazonas and Rondonia, and decreased in Mato Grosso and Para.

Fires were also very prevalent in Paraguay and in Bolivia. It seems that the blackout of thick smoke over the city of São Paulo was caused by fires in Paraguay and not in the Amazon region.

Bolsonaro told reporters that “l used to be called captain chainsaw, now l am Nero setting the Amazon aflame.” There is no question, however, that Brazilian scientists have been facing cuts in their funding, intimidation, and the roll back of environmental protections, and that loggers, wildcat gold prospectors, cattle ranchers and soya farmers, have been emboldened under Bolsonaro.

Eduardo Bolsonaro, not surprisingly, tweeted a “fake news” photo of Greta Thunberg eating her lunch on a train in Denmark, with a photoshopped window looking out on starving children. He cited as a side bar the false accusation that she was supported by George Soros, another favorite target of the right wing activists from Hungary to Brazil.

Ironically, it was not Greta Thunberg who worked for Soros, but Armindo Fraga, the Brazilian Central Bank President under FHC (Fernando Henrique Cardoso), the two term president of Brazil who preceded Lula’s two terms in office, who did indeed work with the mega-investor (and philanthropist) George Soros in New York City. Fernando Henrique Cardoso was in fact a Marxist once upon a time when he was a university professor at the university of São Paulo.

Both sides have formidable allies.

The Bolsonaro family, like Trump, have a devoted following among evangelicals, who provide unshakeable political and electoral support. They also are part of the world wide movement of populist right wing politicians and agitators, and currently head the governments of both the US and the UK. Yet the rain forest agitators are equally well organised and international in scope. They know how to galvanize international attention and mobilize their supporters.

They also have a climate change army of angry youth on their side and they also know the power of WhatsApp and the internet. Brazilian Public opinion is in fact firmly on the side of preservation.

Bolsonaro’s popular evaluation has fallen from 51% to 42% in the most recent public opinion polls, and his negative rating risen from 45% to 55%.

While 80% have heard about the government’s plans to open up indigenous areas to economic exploitation, 93% favour their protection.

But why is it that such a large part of the Amazon Basin is Brazilian territory, and why are the Brazilian military so defensive about the Amazon?

The answer lies in large part in history, the military’s strategic views of ”developmentalism” where the opening up of roads in the Amazon and dams have been priority.

In recent years this has been fortified by the vast expansion of cattle ranching and soya agricultural business, and the linking of this development to the rise of exports to China.

The agribusiness interests are a solid political bloc in the Congress and one of the key pillars of Bolsonaro’s political support, not only in the Congress, but also among the large rural ranchers, slaughter house owners, and exporters of beef, pork and soya.

The historical roots are deep.

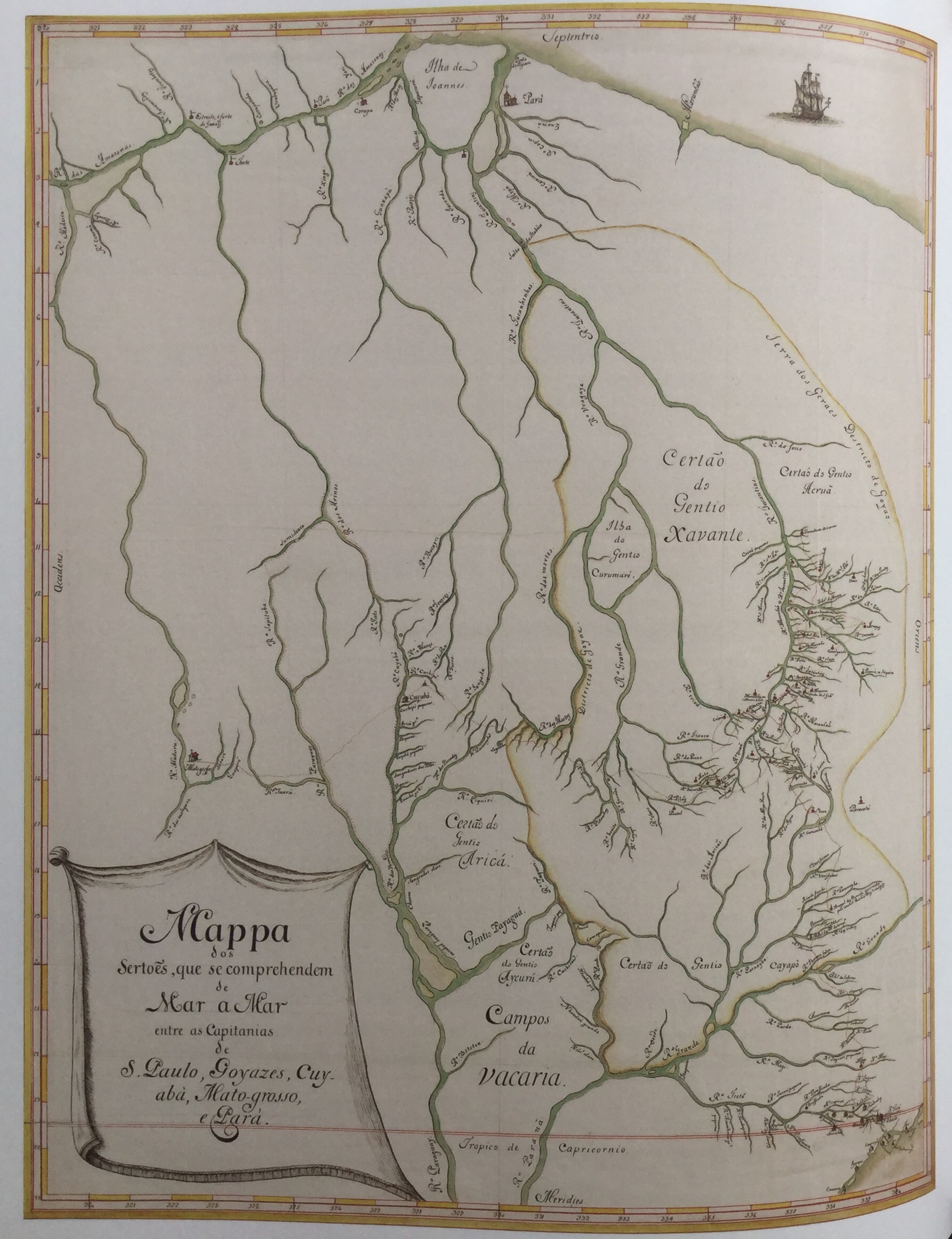

The inland boundaries of Brazil were essentially established in the mid-18th century.

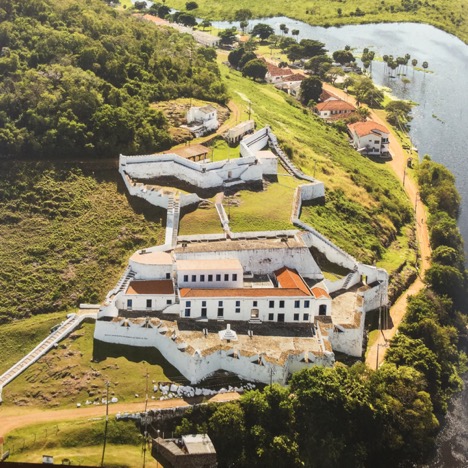

This was the result of the geo-strategic vision of the Portuguese who established riverine routes from the mouth of the Amazon at Belém, via the Amazon, Madeira and Guaporé rivers, to the Far West and the frontiers of Mato Grosso and Cuiabá.

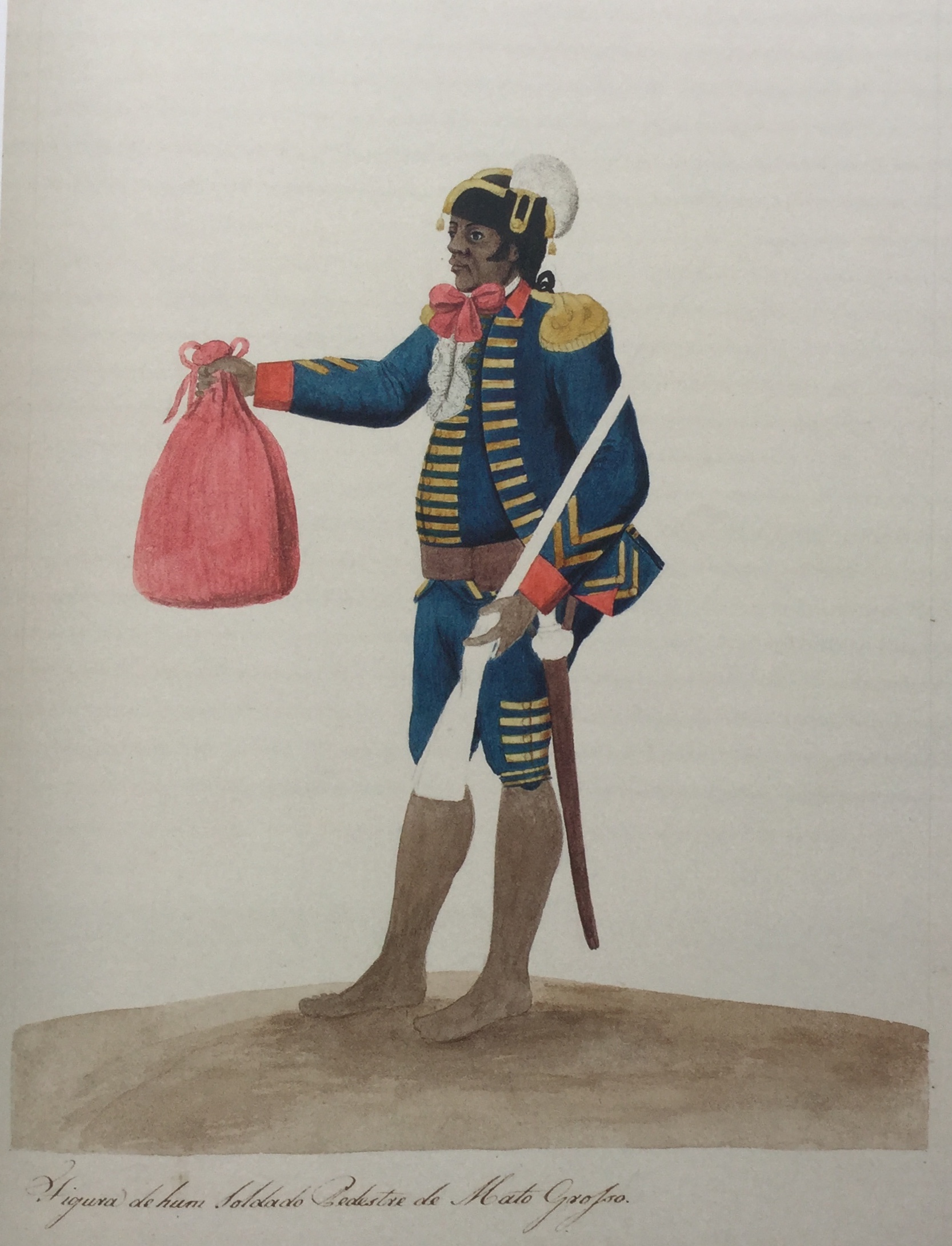

These inland riverine routes were sustained by canoe convoys which linked the Atlantic to the far reaches of the western inland backlands, and the Portuguese established a network of fortresses to protect their inland frontier outposts.

This meant that Brazil obtained its vast territorial dimensions in broad outline in South America well over a century before the USA reached across the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean (and incorporated vast tracts of land along the Mississipi river basin from the French by the Louisiana purchase in 1803, and large tracts of land in the mid-nineteenth century in Texas, California, and the West from Mexico).

This also explains why two thirds of the South American population speaks Portuguese and not Spanish, and why two thirds of the Amazon basin is within Brazil.

When the Portuguese court moved to Brazil in 1807 to escape Napoleon’s invasion of Portugal, it brought with it a geo-strategic vision which included establishing frontiers to protect its riverine communication.

This involved seizing French Guiana, which the Portuguese government, then based in Rio de Janeiro, did by sending an expeditionary force to take Cayenne in 1809.

French Guiana remained part of the Brazil based Portuguese empire until the French took formal possession again in 1817.

The same geo-strategic ambitions had also been present for a long time in the South, and Portugal had a long established outpost on the Rio de la Plata, first established in 1680, at Colonia, opposite Buenos Aires.

The city of Colonia was much disputed for over a hundred years, and Brazilian attempts to retain the city led to the war between the Brazilian empire and the newly independent united provinces of the Rio de la plata (Argentina) between 1825 and 1828, which led to the British intervening to guarantee the emancipation of Uruguay while Brazilian navigation on the Rio de la Plata was assured.

But the Brazilian military always deployed their forces subsequently with a eye to the perceived threat on the southern frontier.

The Jesuits were of course the victims of the territorial disputes between Portugal and Spain in the 18th century over their inland South American borders.

They were first expelled from Brazil in the mid-1750’s since their missions were all situated along the dividing line between the Iberian Powers and in the Amazon.

The current Pope in Rome is it should be remembered, an Argentinian Jesuit. He will certainly remember this history and the jesuits achievements with the indigenous populations in South American as well as the tragedy of their 18th century dispossession.

It is not at all surprising at all that that the pope received cacique Raoni Metuktire at the Vatican on the 27 September.

Raoni is seeking a million euros to better protect the Amazons Xingu reserve, home of many indigenous peoples from farmers, and fire, and from Jair Bolsonaro and his minions.

The featured graphic shows a map from the second half of the 18th century with detailed indications of towns villages, fortresses, and other places along the routes from São Paulo, through the mines of Goiás and Mato Grosso to Para and the island of Joanes, present day Marajó.