The United States and Portugal in the Time of the 18th Century Revolutions

Fortuitously for the Portuguese authorities, they were able to hide the Minas Conspiracy from international attention.

In 1789 the attention of the world was focused on the dramatic developments in Paris where the French Revolution had broken out. The Bastille was stormed on July 14, and in October Louis XVI was forced by an angry mob to leave Versailles for the Tuileries Palace in Paris.

Furthermore, in 1789 the United States was hoping to negotiate a commercial treaty with Portugal. In support of Britain, Portugal had closed its ports to American shipping on July 4, 1776, an ironic (but accidental) coincidence with the date of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia.

Benjamin Franklin was instructed to address the Portuguese ambassador in Paris, D. Vicente de Sousa Coutinho, and to complain about the shipping decree. In the letter signed by Franklin and Silas Deane, the American representatives in France, on July 16, 1777, reaffirmed the “desire of the United States to live in peace with Portugal and requested in the name of the Congress that the measure be withdrawn.”

The Portuguese, however, sent a copy of Franklin’s letter on to the British, noting “in your cause, you see, we are exposed to similar insults.” On February 6, 1778, France recognized American independence and entered into a formal alliance with the United States. In July 1778 France engaged in combat for the first time on the American side.

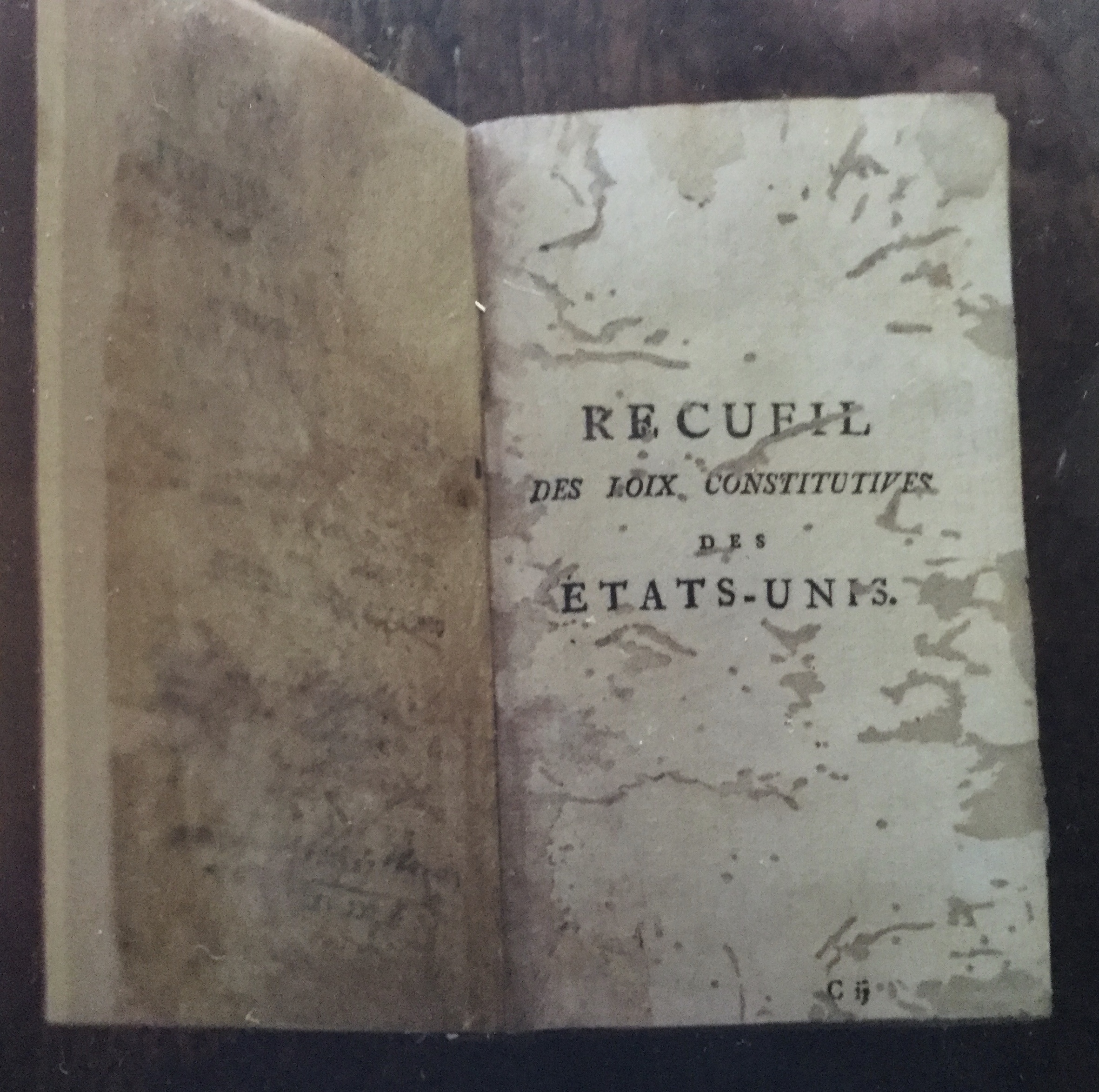

The publication of the Recueil and its dedication to Franklin in 1778 was an important part of the effort by the American commissioners to persuade the French to support the American cause.

Between 1778 and 1783 the Portuguese quietly and repeatedly showed a willingness to provide aid to the Americans up to the point that their treaty obligations to the British would allow. The Portuguese also believed that a fragmented British Empire could serve Portugal’s interests by establishing a countervailing power in the North Atlantic world.

Portugal recognized the independence of the United States on February 15, 1783, and a decree abolished the edict of July 4, 1776, and directed that “in all ports of these realms… passage and entry shall be given to all ships arrived from Northern America.” Between 1783 and 1786 negotiations took place in Paris between the Portuguese ambassador Vicente de Sousa Coutinho and Franklin.

{José Calvet de Magalhães, Portugal and the Independence of the United States (Lisbon: Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros, 1963); Timothy Walker, “Atlantic Dimensions of the American Revolution: Imperial Priorities and the Portuguese Reaction to the North American Bid for Independence (1775–83),” Journal of Early American History 2, no. 3 (2012): 247–85; James Piecuch, “A War Averted: Luso-American Relations in the Revolutionary Era, 1775– 1786,” Portuguese Studies Review 5, no. 2 (1997); Jose Calvet de Magalhães, História das relações diplomáticas entre Portugal e os Estados Unidos da América (1776–1911) (Lisbon: Publicações Europa-América, 1991), 15–67.)

In November 1785 John Adams, the U.S. envoy in London, had a long conversation with the Portuguese envoy, Luis Pinto de Sousa Coutinho. Luis Pinto had recently arrived from Lisbon, and the two envoys discussed in detail the prospects for a commercial treaty between the United States and Portugal with an enumeration of their respective desires.

Luis Pinto had been the governor of Mato Grosso on the far western frontiers of Brazil. He made it clear to Adams that “the Americans could never be admitted to Brazil.” In mid-March 1786, Jefferson crossed the English Channel and arrived in London from his post as the American envoy in France. Jefferson and Adams continued the negotiations for a commercial treaty with Luis Pinto.

A preliminary treaty was signed by Adams and Jefferson on April 24, 1786, though it was never approved or cosigned in Lisbon. The Americans’ demand for access to Brazil was again totally rejected. Jefferson, however, in 1785, had already recommended a league between Portugal and the United States in defense of American shipping in the Mediterranean against pirates from Morocco, Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis.

In May 1786, Portugal’s naval squadron was instructed by Lisbon to “defend and protect American ships from harassment and attacks.” Jefferson was well aware of Virginia’s commercial interests in exports to Portugal.

(Calvet de Magalhães, Portugal and the Independence of the United States, 17–67. Calvet de Magalhães details the various reports on the conversations from Adams in Paris, Jefferson in Paris and London, Luis Pinto in London, Vicente de Sousa Coutinho in Paris, and Martinho de Mello e Castro in Lisbon. Adams had his initial conversations with Vicente de Sousa Coutinho in Paris.)

The Bill of Rights proposed by James Madison in the House of Representatives was approved on September 25, 1789, and these amendments to the United States Constitution were then sent to the various North American states for ratification.

This process was completed on December 15, 1791. These developments in the United States made the Articles of Confederation, the key constitutional text published in the Recueil, obsolete. Benjamin Franklin had met with Felix Antonio Castrioto, a Portuguese journalist living in Paris who had published three pamphlets in France supporting the American cause.

After Queen Maria’s accession to the Portuguese throne in 1777 and the fall from power of the Marquês de Pombal, Castrioto returned to Portugal carrying the letter to the Portuguese foreign minister from Franklin and Deane.

Castrioto also petitioned the Portuguese court to lift the ban on American shipping, and he resumed the publication of the Gazetta de Lisboa. On September 18, 1778, he reprinted the “Resolution of the Province of Pennsylvania, taken by its Respective Assembly, with the purpose of Reaffirming the Sovereignty and Independence of the United States of America.”

Castrioto observed: “The division between England and her Colonies represents the most memorable Revolution that we have had in our world, because the consequences which will come of it will necessarily have a great influence on Calvet de Magalhães, Portugal and the Independence of the United States,

(The conciliatory letter from Franklin was conveyed to Portugal by Castrioto. The document is now in the Portuguese archives and has the annotation: “Original in English by Franklin and Another Agent of the Insurgents of English America.” Torre do Tombo (Portuguese National Archives) Arquivo do Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros, caixa 1, no. 1, letter of B. Franklin and S. Deane to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Portugal, dated July 16, 1777.}

Castrioto spoke prophetically about the “memorable Revolution” in transatlantic affairs. Brazilians would also recognize the revolutionary, republican, as well as the anti-colonial, message and the model that the establishment of the United States of America represented, most especially those young Brazilian students who were studying at the reformed University of Coimbra in Portugal and who were continuing to pursue their postgraduate studies in France at the University of Montpellier and the University of Bordeaux.

Ironically, by 1790 the constitution of the Republic of Pennsylvania, published with great emphasis in the Recueil, had been substantially rewritten to diminish its democratic provisions and to strengthen the power of the executive.

(Letter of Felix Antonio Castrioto to the secretary of state, Ayres de Sá e Mello, November 12, 1777, caixa 1, no. 3. Calvet de Magalhães published a facsimile of the letter from Franklin and Deane of July 1777. See also J. Paul Selsam, The Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776: A Study in Revolutionary Democracy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1936); Robert F. Williams, “The Influences of Pennsylvania’s 1776 Constitution on American Constitutionalism during the Founding Decade,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 112, no. 1 (1988): 25–48; Kenneth Owen, Political Community in Revolutionary Pennsylvania 1774–1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). Francisco Xavier Machado witness statement, 1, Testemunha 20a, 188–91; Casa do Desembargador Pedro José Araújo de Saldanha, Vila Rica, June 26, 1789; Testemunha 13a, João Dais da Motta, said that the conspirators had spoken of aid from France (some ships) and England, 177.)

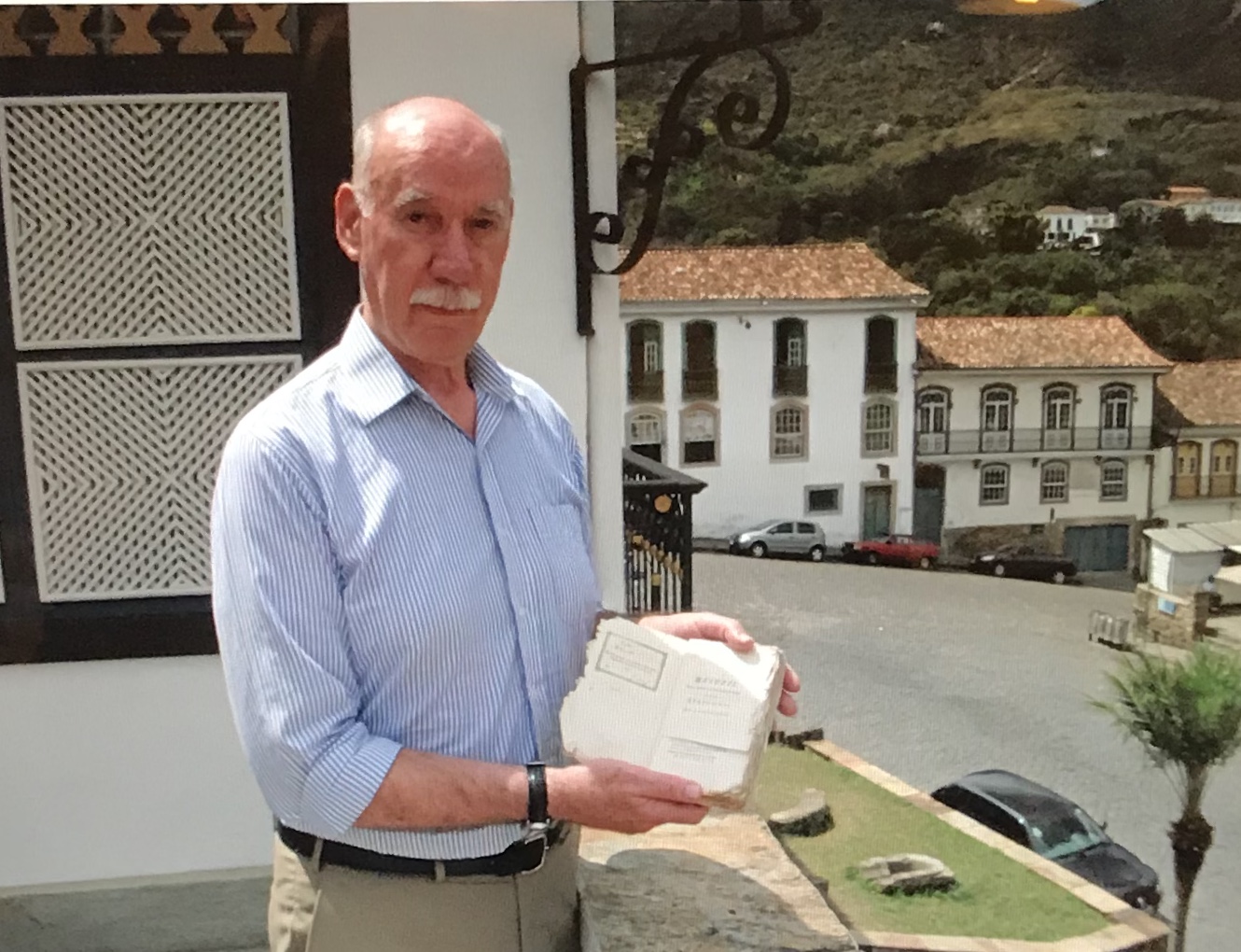

Featured Photo: Professor Maxwell holding his copy of the Recueil during his recent visit to Brazil.

This article is part two of a series:

Imagined Republics: The United States of America, France, and Brazil (1776–1792)