A Key Mission for Maritime Autonomous Systems: Enabling an Undersea Infrastructure Protection Enterprise

Events like the destruction of Nord Stream II or the threats to North Sea Oil rigs or wind farms remind us of the central significance in today’s security and military calculations of infrastructure protection. Conflict is no longer focused simply on direct military action, but on so-called gray zone areas which are entailed in adversaries degrading the infrastructure of their competitors.

No area is of more importance in todays’ information age than undersea infrastructure in support of the movement of communications and data. Yet the focus to date of the maritime autonomous systems which work undersea issues has largely been confined to the oil and gas industry and to the question of repairing undersea infrastructure in support of that industry.

But now infrastructure protection and warfare includes undersea cables of various sorts, notably critical choke points in moving data, communications and information. And the role of maritime autonomous systems in supporting a security and warfighting effort in this area are critical in delivering mission success.

At the DSEI show in London, I was able to meet with Christopher Lade, Head of Marketing and Sales (Maritime) at SAAB UK, to discuss both the challenge and SAAB’s contribution to this area of security and defense.

Lade noted: “The relevance and vulnerability of undersea infrastructure has become apparent in the various examples you mentioned. The scale of the problem is significant because of how much infrastructure is on the seabed. For example, for the UK, more than 90% of our communications pass through undersea cables.”

The size of the infrastructure makes protecting it all virtually impossible. Lade underscored: “We need to focus on the critical choke points where all the cables come together.”

He argued that we needed to focus not simply on undersea infrastructure protection but upon what he referred to as “undersea infrastructure operations.” And such operations needed to encompass both defense and offense – if an adversary has decided to attack your undersea infrastructure, clearly one needs to consider offensive operations as well.

This is very much the same path as cyber operations has followed by the liberal democracies in considering that defense alone is not enough is this domain of security and defense operations.

The challenge among the European nations, for example, is to have shared data and to be able to operate on that data,

In terms of SAAB systems, Lade noted that SAAB’s Seaeye Falcon, their smallest Remotely Operated Underwater Vehicle or ROV can be used to provide information with regard to change detection, to identify where targets have been laid and then “we will go down and neutralize those targets and recover them.” Other SAAB systems which would participate in such an effort are their Sea WASP and the COUGAR.

But these are early days in shaping what Lade referred to as “undersea infrastructure operations” which he prefers to the term seabed warfare.

The challenge is to pull a maritime domain awareness picture together that includes the undersea seabed, not just the surface. The question though is whose responsibility is this nationally or within international organizations such as NATO or the EU? Sorting out who is in charge is critical in determining the requirements to be met by the underwater maritime autonomous systems to deliver the performance required for the mission.

This is clearly a work in progress but one in which maritime autonomous systems will provide critical capabilities to mission success.

This month NATO and Portugal are holding exercises in which maritime autonomous systems are being coordinated to deal with new ways to do maritime operations, including seabed operations.

This was the September 19, 2023, NATO press release on the exercises:

Two exercises focusing on the integration of new maritime technologies into NATO operations and the ability of autonomous underwater vehicles to operate together are being held in Portugal this month.

Starting on Monday (18 September 2023) the NATO-led exercise Dynamic Messenger 23 focuses on integrating Maritime Unmanned Systems into operations, including personnel, training and readiness issues. Dynamic Messenger 23 gathers more than 2000 civilian and military personnel on shore and on board ships as part of the exercise. Fourteen NATO Allies, including the host nation Portugal, are participating in the exercise, together with partner Sweden. This is the second iteration of the Dynamic Messenger series that started in 2022. The exercise is conducted under the joint leadership of NATO’s Allied Command Transformation in the United States and NATO’s Allied Maritime Command MARCOM in Northwood, UK.

Exercise REPMUS 23 (Robotic Experimentation and Prototyping with Maritime Unmanned Systems) takes place in the same region and focuses on capability development and interoperability. REPMUS is led by the host nation Portugal with NATO as a key player since 2019. The exercise is co-organised by the NATO Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation (CMRE), the University of Porto’s Laboratory for Underwater Systems and Technology (LSTS), and NATO’s Maritime Unmanned Systems Initiative (MUSI). Fifteen NATO nations are participating in the exercise, along with partners Ireland and Sweden.

Both REPMUS 23 and DYNAMIC MESSENGER 23 have developed significant partnerships between the private sector and academia, and provide guidance for technology advancements, operational concepts, doctrine, and future work programmes. Both exercises are being held around the Troia Peninsula, in Portugal. Exercise Dynamic Messenger 23 takes place from 18 to 29 September 2023 and Exercise REPMUS 23 takes place from 11 to 22 September 2023.

After DSEI, Lade was departing to Portugal to participate in these exercises.

The Saab Seaeye Falcon: The Professional Portable Underwater Vehicle

“The Falcon concept is the most successful underwater electric robotic system of its class and is proven in numerous intricate and demanding missions across many commercial, security and scientific sectors.

“Equipped with Saab Seaeye’s advanced iCON™ intelligent control system the Falcon provides exceptional vehicle control and diagnostic data as well as the ability to customise the pilot display and enable features such as station keeping.

“The Falcon is lightweight, sized just one metre long and is rated to a depth of 300m.”

Sea Wasp

“Sea Wasp was designed to successfully locate, identify and neutralise IEDs, especially in confined areas and challenging conditions like strong current, ports and harbours. With a high degree of operational autonomy, Sea Wasp takes vessels and operators out of harms way, providing a safer underwater solution to ordnance disposal.

“Saab’s Sea Wasp underwater vehicle is a mobile system that can operate in harbours, lakes, rivers and other waterways. Underwater orientation is performed by video cameras, LED lights and wideband sonar, primarily to locate targets that may have been placed on a ship’s hull, a harbour wall or the seabed. Sea Wasp can be used in a wide range of civil and military operations, making it extremely cost effective for customers. Due to its small size and footprint, its manoeuvrability and its relatively light weight, Saab’s Sea Wasp underwater system is perfectly designed to meet all kinds of challenges.”

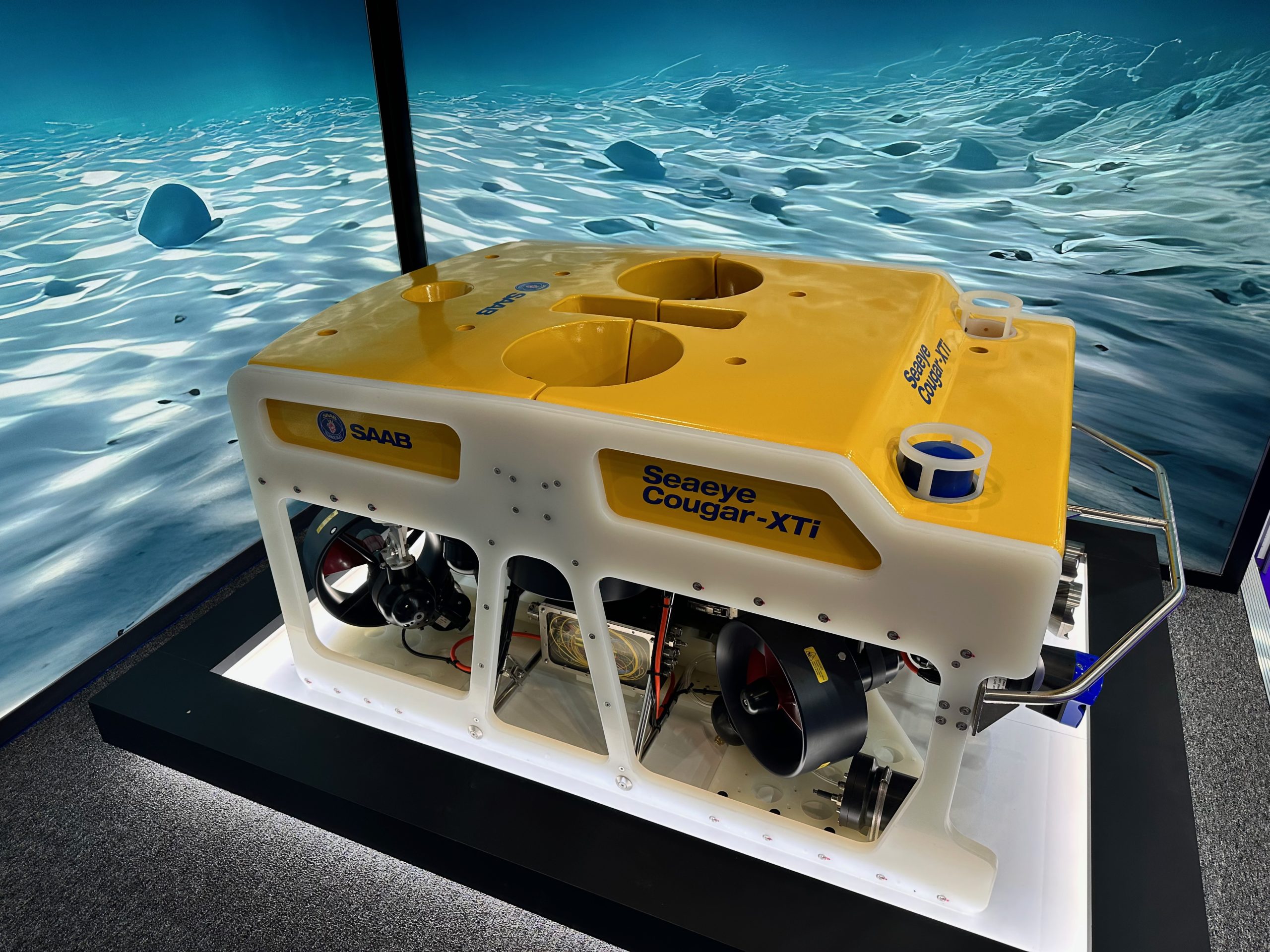

Cougar-XT

“The Cougar-XT is a highly flexible, small, yet extremely powerful vehicle depth rated to 2000m. Six 500 Volts DC thrusters provide precise handling and control in strong current environments.

“Designed to accommodate heavy duty tooling via a system of quick-change tool skids, the Cougar-XT is ideal for survey work, IRM, drill support, light construction projects and salvage support operations.

“The surface equipment for the Cougar-XT can be provided as free-standing units or integrated into a control cabin.”

The featured photo is of the Cougar which the author shot at the DSEI show.

Note: In an article by Tim McGeehan which was published by CISME on September 19, 2023, the author addressed in a comprehensive manner the “unfolding maritime competition over undersea infrastructure.”

In that article, he underscored: “Developing increased deep ocean and seafloor capabilities does not imply a future of large manned platforms operating at full ocean depth. Instead, it could be a highly distributed and self-organizing collection of many small, affordable, and attritable assets. In many cases, existing sensors and payloads could be repurposed but modified and encapsulated for depth.

“Persistent deep ocean capabilities will also support maritime domain awareness, with routine monitoring of our own seabed infrastructure to detect and mitigate attempts at physical tampering. Novel projects are underway to repurpose existing commercial communications seabed infrastructure for sensing applications….”