Toilet Paper and Total War

The lessons that prepare defence forces and government institutions for crisis responses need not come from history books.

Lessons can come from extrapolating what we witness every day; from events that capture tangible and intangible aspects of sustaining normal life.

From natural disasters to global pandemics, Australia has had a tumultuous beginning of the year.

This time has been socially, economically and politically testing. The impact of this turbulence on essentially fragile national logistics, commerce and industry capability is starkly evident and has forced the nation to consider its national resilience.

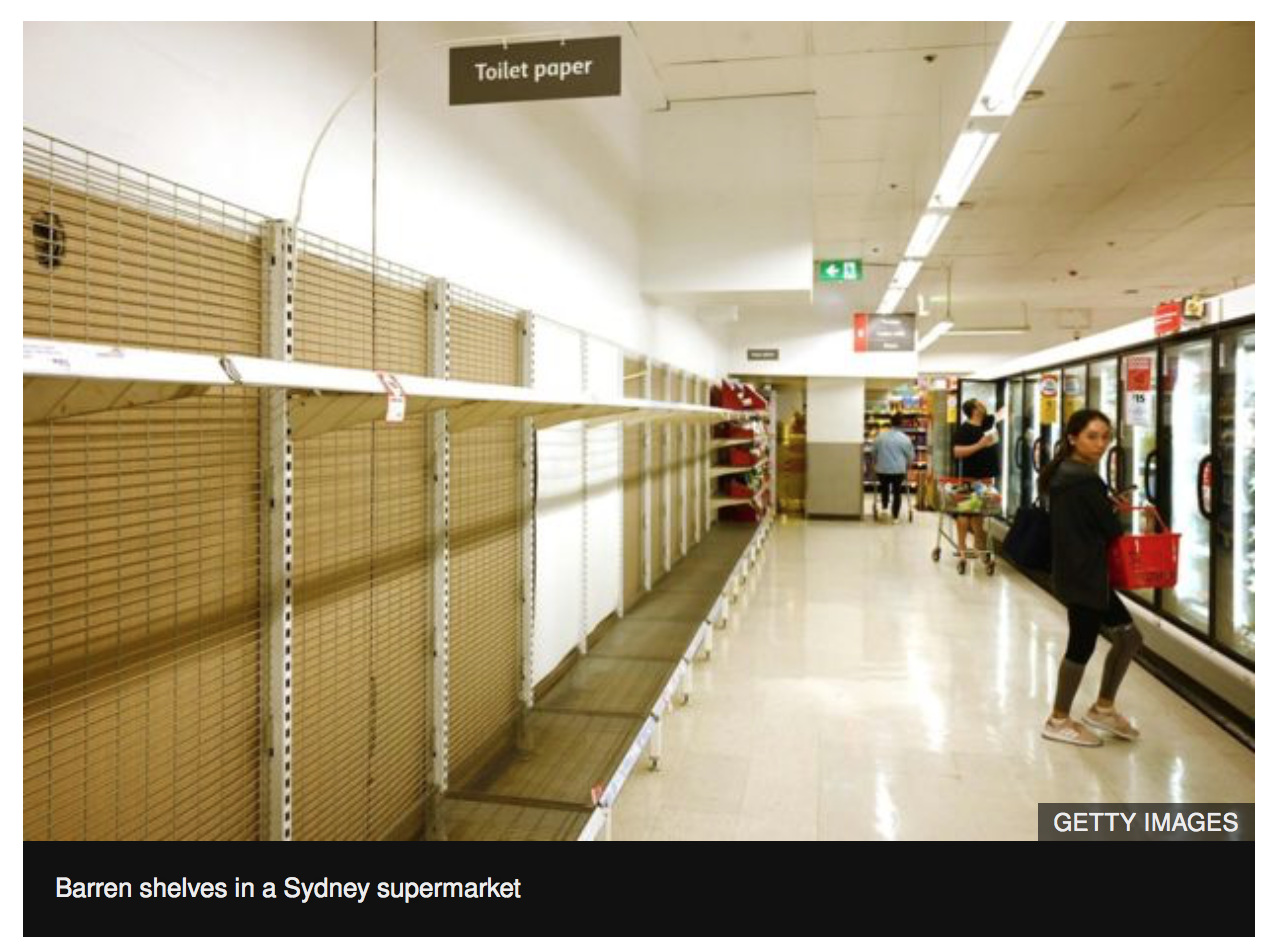

The difficulty experienced in obtaining basic household products – toilet paper for example – as consumers buy in preparation for a state of quarantine that may never come, as trite an issue as it may be, starkly demonstrates how critical human behaviour is in the calculus.

It is a perfect analogy with which to consider military preparedness and strategic resilience.

People naturally gravitate towards the idea that strategic resilience is about maintaining a buffer for emergencies. Inevitably, and for sensible reasons, the topic of national reserves or stocks (or, in the military’s case, ‘war stocks’) is raised.

Enough stockholdings of strategically significant commodities is critically important for national resilience, just as they are for military operations.

The absence of stock is, however, only the ‘front-end’ of the problem in a major crisis.

In some cases, the maintenance of unnecessary stock levels may actually detract from preparedness and resilience; vast quantities of inappropriate strategic reserves consume money and other resources that can be used in other critical areas.

Buffers, insurance and assurance (through planning and governance) are important for resilience, but there are intangible factors that need to be understood.

In military logistics, the greatest behaviour-based harm to logistics performance relates to trust that the logistics system will deliver, and from the impact of ‘psychological effects induced by the [original] deficiency.1

Even if the situation improves commanders will ‘certainly place pressure on their planners and on their own superiors to insure future adequacy of support.’2

Commanders and logisticians at all levels will arbitrarily increase their demands, and others will do their best to meet the new requirement. Hoarding will occur. The military organisation – perhaps even government and industry – will rapidly try to respond to rapidly growing military requirements.

This sounds like a good problem to have; while having surplus production and availability certainly beats dealing with systemic shortages, logistics ‘scaling’ rarely occurs without problems. This ‘under-planning / over-planning’ sequence generally results in oversupply; wasting transport, clogging warehouses, limiting strategic mobility and costing resources that the force can’t spare.3

It was a problem recently seen in the initial operations of Operation Iraqi Freedom, and was one reason for the ‘iron mountains’ of Operation Desert Storm over a decade earlier. If production or availability cannot increase, an inefficient transfer of resources from one area of the battlefield to the other can upend strategy. In these circumstances it becomes difficult for planners to direct resources to the right place, and what can be termed ‘brute force logistics’ – get as much as you can to the place what you believe is of the greatest need – comes.

The parallel with what is going on now with COVID-19 (coronavirus), or what was seen in the shortages of air purifiers and face masks during the Australian bushfire crisis this year, is clear. Australian consumers are fearful.

A normally stable balance of supply and demand is upset by events, with consumer behaviour in panic-buying magnifying the problem.

The ‘world’ is only at the beginning of its industrial and supply-chain response to the virus. Given that it is likely to have a pandemic on its hands, the production, transfer and management of resources globally is, quite obviously, going to be chaotic.

We’re waiting to find out what happens next. Some economists are predicting the global production output loss to enter the trillions of dollars, with global economic conditions likely to become recessionary. It is also possible that a huge multi-lateral economic response will lead to a version of the ‘under-planning / over-planning sequence.’ Governments may launch economic stimulus packages to deploy funding and offset a precipitous decline in trade.

While I won’t pretend to know the answer as to what might happen in a pandemic situation, the ideas of military logistics can offer a window through which to observe the situation. We can, however, use the events before us as a window of our own to consider military preparedness.

What if the scenario was a military crisis rather than a response to natural disaster or pandemic? Imagine we were talking about spare-parts or precision weapons rather than face-masks or toilet paper.

The simultaneous draw upon shared industrial resources by coalition partners might create ‘runs’ on necessary resources and stocks, for without these stocks military forces will be little more than a short-term buffer against the encountered strategic shock.

Preparedness systems fail, logistics processes collapse, and command struggles to regain control. The purpose of Martin Van Creveld’s Supplying War seems to be found in displaying militaries in disarray, and Richard Betts writes of the ‘unreadiness’ of the US military as its first tradition in the book Military Readiness: concepts, choices, consequences4

The ADF has experienced this ‘tradition’ in the past.

Two examples in recent Australian military history spring to mind.

The first was during the deployment of International Forces East Timor in 1999 when a massing coalition force drained the city of Darwin of hardware and deployable consumables, necessitating an ad hoc and inefficient procurement plan to be developed.

The second was during the deployment of the US-led coalition to Iraq in 2003 where because Australia lacked the competitive buying power to procure commercial airlift to support the deployment, it arranged with the US that its Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) would facilitate airlift.

What if the scenario was severe still, and a level of national mobilisation required? Naturally we would see proportionally severe exacerbation of the problems above. Histories of the First and Second World war attest to the problem of over-mobilisation; where the rush to put personnel in the field, on the ocean and in the air outpaces the capacity of industry to provide them with the materiel of war.

The increasing sophistication of modern weaponry, the high standard of materiel modern militaries expect themselves to operate with, the presence of an increasingly specialist workforce, and with lean force structures characteristic of periods of structural demobilisation, will make an incredibly difficult resilience challenge for a modern Western military.

The first losses of battle make the demand for materiel much more critical than the demand for manpower. It takes years to establish production runs capable of supporting the largest forces, especially as the manpower draw to the military draw is the same as to industry. But when industry starts to fulfil the need, it tends to do so in such excess that it is wasteful and a needless draw on limited national resources. The wrong things are produced at the wrong time and delivered to the wrong place.5

The systems of prioritisation and allocation fail, and in the rush to do something good, the best intentions create unforeseen and unwanted problems.

Logistics and preparedness are defined by ‘tangibles’ and ‘intangibles’. These two factors conspire to create complex systems that are difficult to control, especially when the impact of human decisions and behaviours is taken to account.

Until we have quantum computers and artificial intelligence to do the thinking for us, the best we may be able to do is research, study and observe the events before us.

What we may witness in consumer behaviour in highly unusual situations is like what might be witnessed with respect to ‘military behaviour’ in a war or a military crisis.

As ultimately innocuous as a consumer run on toilet paper might be to us now, the situation does tell a story as to how we might see our military logistics systems act in a time of strategic shock.

Understanding how they may act ultimately underwrites military preparedness and, in the case of strategy and national power, creates the national resilience that ultimately determines success in war.

This article was publish on Logistics in War on March 8, 2020.

Footnotes

- Eccles, H., Logistics in the national defense, The Stackpole Company, USA, 1959, p 109

- Ibid., p 109

- Ibid., p 109

- See Van Creveld, M., Supplying War, Cambridge University Press, UK, 2004 (4th edition); Betts, R., Military readiness: concepts, choices, consequences, Brookings, USA, 1995

- It was these observations of the Second World War that led Eccles to develop his theory of the logistics snowball, often caused by the under-planning, over-planning sequence.