The European Direct Defense Challenge: Nordic Perspectives

In an article published by a retired senior Swedish officer, Major General (Ret) Karlis Neretnieks, the evolving Nordic perspectives on the return of direct defense in Europe was analyzed with key questions raised as well.

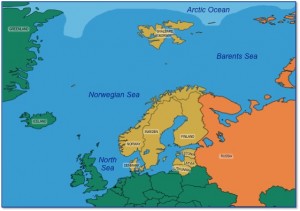

“Scandinavian military security must be seen as a whole where all countries concerned, Norway, Sweden and Finland are heavily dependent on each other in case of a war in the region. A fact quite seldom discussed or analyzed in depth. Something that is quite surprising as it has implications not just for the Scandinavian countries but also for NATO´s possibilities to defend Europe.

He then provides a careful look at that the defense situation in part based on what we already know or should now from the 1930s and its challenges.

“Although Finland has a well-organized “economic defense” with stockpiles of food and other vital necessities a modern society will have great problems if its industry is cut off from the outside world. This leads to perhaps Finland´s greatest vulnerability – its dependence on reasonably safe lines of communications, by sea, air and land.

“If there is an armed conflict in the Baltic Sea region it is very probable that more or less all shipping to and from Finland will cease. Thereby affecting approximately 80 % of Finland´s trade. Finland would become totally dependent on what could be transported through Sweden or in Swedish airspace.

“This interdependence; Finland protecting the northern half of Sweden and Sweden keeping lines of communication open to Finland unfortunately has not been given enough consideration in Swedish defense planning. This of course also has great implications for Finland´s possibilities to receive help from NATO…..

Neretnieks underscored the importance for Sweden and Finland to ensure that they could receive support from allies through the SLOCs in the North Atlantic as well as form Northern Norwegian bases as well. NATO is again planning for shipping reinforcements across the Atlantic and Russia has partly rebuilt, and continues to increase, it its capability to act in the Atlantic.

This makes the defence of northern Norway not just a problem for the Scandinavian countries but for Europe as a whole.

“From the Scandinavian or Nordic point of view these increased Russian capabilities and their strategic importance is quite alarming. Not just that it creates strong motives for Russia to attack NATO facilities in northern Norway, it also threatens the whole regions connections with the outside world. Even if Russia might encounter problems attacking ships and planes moving across the Atlantic it is obvious that isolating the Scandinavian Peninsula would be a quite easy task if NATO could not operate from bases in northern Norway.

“Just as in the case of Finland, both Norway and Sweden are dependent on secure sea lanes for export and import of vital goods and for receiving military help. Both countries, as well as Finland to some extent, build their war planning on help from NATO, in reality from the US.

“The defense of Norway, especially northern Norway, therefore is a vital common interest for all the Scandinavian countries as well as for NATO.”

After further analyses of the situation facing the Nordics, the author then considered some of the key efforts, which they need to make to enhance the defense and security of the Nordic region.

“Considering the dependencies and the vulnerabilities that have been described, what ought to be done?

“Some actions have already been taken.

‘Norway is redirecting its thinking and its preparations towards Article 5 operations. Sweden and Finland have concluded Host Nation Support agreements with NATO.

“They have also signed bilateral agreements with the US and the UK regarding enhanced cooperation in areas as sharing and developing military technology and joint training.

“Both countries are also participating in NATO exercises as Trident Juncture 2018 in northern Norway engaging some 45 000 personnel from more than 30 countries.

Regarding what should to be done on a national level, in general terms it ought to be: Sweden should increase its capabilities to secure Finland´s communications with the outside world and increase its ability to protect Norway´s back, Finland and Sweden together should increase their common capabilities to protect the Aaland Islands and sea lanes across the Gulf of Bothnia, Norway should allocate still more resources to anti-submarine warfare and air defense in the high north.

Although Finland and Norway could and should do a bit more in the areas mentioned above the great culprit at the moment is Sweden.

“Geographically being the hub in the region on which the security of other countries depend it is not taking on the responsibilities it should, thereby jeopardizing not just its own security but also the security of its neighbors. At the moment (2017) Sweden spends just 1 % of GDP on defense, Norway spends 1,6 % and Finland 1,4%….

“Apart from strengthening their own defense capabilities, one other measure that would drastically increase Nordic security, and take cooperation between the Scandinavian countries to much higher level, would be Finland and Sweden joining NATO.

“It would not just solve the problem with an isolated attack against those countries which would put NATO in a very precarious situation when it comes to defend the Baltic States or northern Norway in a later stage, it would also make it possible to coordinate plans and operations between the Scandinavian countries. Making it possible to get more joint fighting power of the money spent on defence. It would also open up for “work sharing” where each country could take on a more specialized role.”1

The Finnish Perspective

The Finns have focused squarely on ways to enhance their capability to resist incursions from the Russians and to work towards expanded ways to enhance democratic military capabilities. They prioritize security of supply and have maintained military inscription system to prepare to mobilize in a crisis as well.

The Finns recognize that this is not enough given the nature of their 21st century competitor. They have established a new Centre to deal with the challenge of not just new ways of conducting influence operations but against European infrastructure as well. And they have done so in a manner, which underscores that a purely national solution is not enough and requires a broader European Union response as well.

The Government of Finland has stood up a new Centre designed in part to shape better understanding which can in turn help the member states develop the tool sets for better crisis management. This is how the Finnish government put it with regard to the new center in its press release dated October 1, 2017.

The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats has reached initial operational capability on 1 September 2017. The Act on the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats entered into force on 1 July 2017, following which Matti Saarelainen, Doctor of Social Science, was appointed Director of the Centre. The Centre has now acquired premises in Helsinki, established a secretariat consisting of seven experts and made the operational plans for this year.

“Hybrid threats have become a permanent part of the Finnish and European security environment, and the establishment of the Centre responds well to this current challenge.

Since early July, rapid progress has been made to allow the Centre to begin its operations. The Steering Board will be briefed on the progress at its meeting next week,” says Jori Arvonen, Chair of the Steering Board of the Centre.

The Centre will launch its activities at a high-level seminar to be held in Helsinki on 6 September. The seminar will bring together representatives of the 12 participating countries, the EU and NATO. Approximately 100 participants will take part in the seminar. The Centre’s communication channel (www.hybridcoe.fi) will also be opened at the seminar. Minister for Foreign Affairs Timo Soini and Minister of the Interior Paula Risikko will speak at the seminar as representatives of the host country. The official inauguration of the Centre will be held on 2 October.

The Centre is faced with many expectations or images. For example, the Centre is not an ´operational centre for anti-hybrid warfare´ or a ´cyber bomb disposal unit´. Instead, its aim is to contribute to a better understanding of hybrid influencing by state and non-state actors and how to counter hybrid threats. The Centre has three key roles, according to the Director of the Centre.

“First of all, the Centre is a centre of excellence which promotes the countering of hybrid threats at strategic level through research and training, for example. Secondly, the Centre aims to create multinational networks of experts in comprehensive security. These networks can, for instance, relate to situation awareness activities. Thirdly, the Centre serves as a platform for cooperation between the EU and NATO in evaluating societies’ vulnerabilities and enhancing resilience,” says Director Matti Saarelainen.

The EU and NATO take an active part in the Centre’s Steering Board meetings and other activities. As a signal of the EU and NATO’s commitment to cooperation, Julian King, EU Commissioner for the Security Union, and Arndt Freytag von Loringhoven, NATO Assistant Secretary General for Intelligence and Security, will participate in the high-level seminar on 6 September.

Currently, the 12 participating countries to the Centre are Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States. EU and NATO countries have the possibility of joining as participant countries.2

During a 2018 visit to the Centre, we interviewed Päivi Tampere, Head of Communications for the Centre, along with Juha Mustonen, Director of International Relations and discussed the approach of the new Centre to the authoritarian states.

The Centre is based on a 21st century model whereby a small staff operates a focal point to organize working groups, activities and networks among the member governments and flows through that activity to publications and white papers for the working groups.

As Tampere put it: “The approach has been to establish in Helsinki to have a rather small secretariat whose role is to coordinate and ask the right questions, and organize the work. We have 13 member states currently. EU member states or NATO allies can be members of our Centre. We have established three core networks to address three key areas of interest. The first is hybrid influencing led by UK; the second community of interest headed by a Finn, which is addressing “vulnerabilities and resiliencies.”

“And we are looking at a broad set of issues, such as the ability of adversaries to buy property next to Western military bases, issues such as legal resilience, maritime security, energy questions and a wide variety of activities, which allow adversaries to more effectively compete in hybrid influencing. The third COI called Strategy and Defense is led by Germany.”

“In each network, we have experts who are working the challenges practically and we are tapping these networks to share best practices what has worked and what hasn’t worked in countering hybrid threats. The Centre also organizes targeted trainings and exercises to practitioners. All the activities aim at building participating states’ capacity to counter hybrid threats. The aim of the Centre’s research pool is to share insight to hybrid threats and make our public outreach publications to improve awareness of the hybrid challenge.”

With Juha Mustonen, who came from the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs to his current position, we discussed the challenges and the way ahead for the Centre.

“Influencing has always been a continuum first with peaceful means and then if needed with military means. Blurring the line between peacetime influencing and wartime influencing on a target country is at core of the hybrid threats challenge. A state can even cross the threshold of warfare but if it does not cross the threshold of attribution, there will be no military response at least if action is not attributed to that particular state. Indeed, the detection and attribution issue is a key one in shaping a response to hybrid threat.”

And with the kind of non-liberal states we are talking about, and with their expanded presence in our societies, they gain significant understanding and influence within our societies so they are working within our systems almost like interest groups, but with a focus on information war as well.

Juha Mustonen added: “Adversaries can amplify vulnerabilities by buying land, doing investments, making these kinds of economic interdependencies. They can be in dialogue with our citizens or groups of our citizens, for example, to fostering anti-immigrant sentiments and exploiting them to have greater access to certain groups inside the European societies. For example, the narratives of some European far right groupings have become quite close to some adversaries’ narratives.”

In other words, the challenge now is becoming a mixing of kinetic power with domestic intrusions designed to shape Western positions and opinion as well.

Juha Mustonen underscored the nature of the challenge associated with direct defense in Europe today as follows: “Adversaries are using many instruments of power. One may identify a demonstration affect from the limited use of military power and then by demonstrating our vulnerabilities a trial of a psychological affect within Western societies to shape policies more favorable to their interests.

“If you are using many instruments of power, below the threshold of warfare, their synergetic effect can cause your bigger gain in your target societies, and this is the dark side of comprehensive approach. The challenge is to understand the thresholds of influence and the approaches. What is legitimate and what is not? And how do we counter punch against the use of hybrid influencing by Non-Western adversaries? How can we prevent our adversaries from exploiting democratic fractures and vulnerabilities, to enhance their own power positions? How do we do so without losing our credibility as governments in front of our own people?”[2]

Clearly, a key opportunity for the center is to shape a narrative and core questions which Western societies need to address, especially with all the conflict within our societies over fake news and the like.

The Danish Perspective

During a conference held in Copenhagen on October 11, 2018, the Danish Minister of Defence provided an overview on how the government views defence and security, particularly challenges in direct defence of Denmark and Europe – cyber war posed by Russia and the need to enhance infrastructure defence are of key concern.

The lines between domestic security and national defense are clearly blurred in an era where Russians have expanded their tools sets to target Western infrastructure. Such hidden attacks also blur the lines between peace and war.

Within an alliance context, the Danes and other Nordic nations, are now focusing on direct defense as their core national mission. This will mean a shift from a focus on out of area operations back to the core challenge of defending the homeland. Russian actions, starting in Georgia in 2008 and then in the Crimea in 2014, have created a significant environment of uncertainty for European nations, one in which a refocus on direct defense is required.

Denmark is earmarking new funds for defense and buying new capabilities as well, such as the F-35. By reworking their national command systems, as well as working with Nordic allies and other NATO partners, they will find more effective solutions to augment defensive force capabilities in a crisis.

It was very clear from our visits to Finland, Norway and Denmark over the past few years, that the return to direct defense has changed as the tools have changed, notably with an ability to leverage cyber tools to attack Western digital society to achieve political objectives with means other than use of lethal force.

This is why the West needs to shape new approaches and evolve thinking about crisis management in the digital age. It means that NATO countries need to work as hard at infrastructure defense in the digital age as they have been working on terrorism since September 11th.

New paradigms, new tools, new training and new thinking is required to shape various ways ahead for a more robust infrastructure in a digital age. Article III of the NATO treaty underscores the importance of each state focusing resources on the defense of its nation. In the world we are facing now, this will mean much more attention to security of supply chains, robust security of infrastructure, and taking a hard look at any vulnerability.

Robustness in infrastructure can provide a key defense element in dealing with 21st century adversaries, and setting standards may prove more important than the buildup of classic lethal capabilities. A return to direct defense, with the challenge of shaping more robust national and coalition infrastructure, also means that the classic distinction between counter-value and counter-force targeting is changing. Eroding infrastructure with non-lethal means is as much counter-force as it is counter-value.

We need to find new vocabulary to describe the various routes to enhanced direct defense for core NATO nations. A new strategic geography is emerging, in which North America, the Arctic and Northern Europe are contiguous operational territory that is being targeted by Russia, and NATO members need to focus on ways to enhance their capabilities to operate seamlessly in a timely manner across this entire chessboard.

In an effort to shape more interactive capability across a common but changing strategic geography, the Nordic nations have enhanced their cooperation with Poland and the Baltic states. They must be flexible enough to evolve as the reach and lethality of Russia’s air and maritime strike capabilities increases.

Clearly, tasks have changed, expanded and mutated. An example of a very different dynamic associated with direct defense this time around, is how to shape a flexible basing structure. What does basing in this environment mean? Can allies leverage national basing with the very flexible force packages needed to resolve a crisis?

One of the sponsors of the October 2018 Danish Conference was Risk Intelligence, provide a very cogent perspective on how to look at the challenge. The CEO of Risk Intelligence, Hans Tino Hansen, a well-known Danish security and defense analyst explains the new context and challenges facing the Nordic countries:

“We need to look at the Arctic Northern European area, Baltic area, as one. We need to connect the dots from Greenland to Poland or Lithuania and everything in between. We need to look at the area as an integrated geography, which we didn’t do during the Cold War.

“In the Cold War, we were also used to the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact being able to actually attack on all fronts at the same time, which the Russians wouldn’t today because they are not the power that they used to be. And clearly we need to look beyond the defense of the Baltic region to get the bigger connectivity picture.”

He went on to assert the need to rethink and rebuild infrastructure and forces to deal with the strategic geography that now defines the Russian challenge and the capabilities they have […] to threaten our interests and our forces.”

Evaluating threats across a spectrum of conflict is the new reality. “We face a range of threats in the so-called gray area which define key aspects of the spectrum of conflict which need to be dealt with or deterred.”

A system of crisis identification with robust procedures for crisis management will go a long way towards effective strengthening of infrastructure in the face of the wider spectrum of Russian tools.

“A crisis can be different levels. It can be local, it can be regional, it can be global and it might even be in the cyber domain and independent of geography. We need to make sure that the politicians are not only able to deal with the global ones but can also react to something lesser,” Hansen says. The question becomes how to define a crisis.

“Is it when x-amount of infrastructure or public utilities have been disrupted or compromised? And for how long does the situation have to extend before it qualifies as a crisis?

“This certainly calls for systems and sensors/analysis to identify when an incident, or a series of incidents, amount to a crisis. Ultimately, that means politicians need to be trained in the procedures necessary in a crisis similar to what we did in the WINTEX exercises during the old days during the Cold War, where they learned to operate and identify and make decisions in such a challenging environment.”[3]

In short, the Russian challenge has returned – but in a 21st century context that incorporates incredibly invasive infrastructure and other types of engagement within the liberal democracies as well.

Direct defense strategies must include these threats as part of any comprehensive national security concept and approach.

Footnotes

- Kalis N, “NATO and Scandinavian Strategic Interdependence, “ karlisn.blogspot (October 4, 2018), http://karlisn.blogspot.com/2018/10/nato-and-scandinavian-strategic.html?m=1.

- “European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats Starts Operating in Helsinki,” Finnish Ministry of the Interior, September 1, 2017, http://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/article/-/asset_publisher/1410869/eurooppalaisen-hybridiosaamiskeskuksen-toiminta-kaynnistyy-helsingissa