U.S. Spacepower: An Update and the Road Ahead for the Next Administration

The past year has seen the most sweeping transformation of U.S. spacepower in decades.

In the words of Stephen L. Kitay, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, the United States is seeing “the most significant transformation in the history of the National Security Space Program,” involving “an enterprise-wide transformation from approaching space as a support function, to approaching space as a warfighting domain in which we are postured to compete, deter, and win.”

In August 2019, the United States established the U.S. Space Command (USSPACECOM) as the eleventh combatant command, which combines capabilities from each of the five military services and applies them to execute missions in the space domain. Its goal is “bring[ing] focused attention to defending U.S. interests in space” and “accelerating the integration of space capabilities into other warfighting forces.”

Prioritizing space as a warfighting domain, the USSPACECOM focus areas are:

- deterring or defeating aggression in, from, and to space;

- defending the complete span of U.S. and allied space interests and assets;

- delivering lethal spacepower and ready joint warfighters to other COCOMS; and

- serving as the DOD manager for human spaceflight.

The USSPACECOM’s two subordinate commands are the Combined Force Space Component Command (CFSCC) and Joint Task Force Space Defense (JTF-SD).

In December, the Defense Department stood up the U.S. Space Force (USSF) as a military service branch of the U.S. Armed Forces, the first one in more than 70 years, though its personnel size is smaller than any other military service branch. Analogous to the position of the U.S. Marine Corps within the Department of the Navy, the USSF is formally a coequal branch with the United States Air Force within the Department of the Air Force, both overseen by the Secretary of the Air Force.

The USSF’s main functions are to organize, train, and equip space forces and provide these capabilities to the Joint Force via appropriate components in the combatant commands, which will apply spacepower in all five domains – air, land, sea, cyberspace, as well as outer space.

The USSF will have a flatter command structure than the previous Air Force Space Command, with three rather than five echelons aiming for “a lean, agile and mission-focused organization.”

The three levels of the command structure are:

- Field Commands (led by an O-9 or O-8);

- Operational support or specialized Mission Deltas (equivalent to Army Combat Teams or Air Force Expeditionary Wings, led by an O-6) along with Garrison Commands for installation support; and

- Squadrons at the lowest level, led by an O-5.

Formerly the 14th Air Force, the restructured Space Operations Command (SpOC, headed by a three-star general officer) is the primary provider of space personnel and capabilities for warfighting operations conducted by combatant commanders, other elements of the Joint Force, and international partners.

The Space Systems Command (SSC, headed by a three-star), is responsible for developing, acquiring, fielding, and sustaining military space systems through developmental testing, on-orbit checkout, and maintenance. The SSC also oversees the USSF science and technology activities such as the Space and Missile Systems Center, the Commercial Satellite Communications Office, and other former USAF program offices being transferred to the new USSF, plus any new ones.

The Commercial Satellite Communications Office (CSCO, headed by civilian employee Clare Grason) has launched an Infrastructure Asset Pre-Assessment Program to help the USSF, which has sole authority for procuring military communications satellites, acquire more cyber secure COMSATS from commercial and other partners.

A new Space Force Acquisition Council (SFAC) is intended to “oversee, direct, and manage acquisition and integration of the Air Force for space systems and programs in order to ensure integration across the national security space enterprise.” The Council directs the activities of the Space Development Agency (SDA), Space and Missile Systems Center, and Space Rapid Capabilities Office. The SDA, formed in March 2019, will become part of the USSF in late 2022. These bodies aim to leverage the vast U.S. commercial space sector for cost-effective and innovative solutions.

Finally, the Space Training and Readiness Command (STARCOM) headed by a two-star after it stands up in 2021), was stood up at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado to train, educate, inspire, empower, and transform new spaceprofessionals, with appropriate ethos and skills, into combat-ready space troops. This task is critical for building enduring space power in coming years.

Though some two dozen units have been transferred from the USAF to the USSF, the Space Force still has the smallest number of active duty military personnel of any service branch. The U.S. Air Force will provide most of the defense support functions for the new Space Force, including security forces, civil engineers, human resource managers, financial managers, public affairs, and medical and legal personnel. Civilian contractors will maintain and operate many assets, but only uniformed personnel will be able to engage in actual warfighting.

On June 17, 2020, the Pentagon published a new Defense Space Strategy to provide strategic direction for transforming the U.S. military space policies, capabilities, operations, doctrine, and partnerships. It established three general objectives for the Pentagon’s space activities: maintain space superiority; provide space support to national, joint, and combined operations; and ensure space stability. The Strategy identified four lines of effort to attain these goals:

- Build a comprehensive military advantage in space by developing the Space Force in general and the doctrine, expertise, culture, and capabilities needed to manage current and future threats

- Integrate military space power into national, joint, and combined national security operations

- Shape the strategic environment by working internationally to develop responsible standards of space behavior

- Cooperate with foreign allies and partners as well as domestic industries and other U.S. government departments and agencies.

The inaugural Space Capstone document published this month, entitled “Spacepower,” provides high-level doctrine to guide the USSF in executing multidomain operations. Its five sections address various aspects of developing and employing U.S. spacepower: the distinct nature of the space domain, national spacepower, military spacepower, employment of space forces, and military space forces. These sections describe:

- why “spacepower” is a distinct form of military power but on par with the other five domains of landpower, seapower, airpower, and cyberpower

- how spacepower is employed; the unique aspects of the space domain

- the relationship between national and military spacepower; and an assessment of the expertise needed to succeed in this realm

The publication covers such issues as common terminology, operational and tactical doctrine, training and education, mission analysis, decision making, and the development of space strategy in support of U.S. national security. The Capstone will serve as the basis for developing the Force’s operational and tactical doctrine.

Despite its historical association with the U.S. Air Force, spacepower has been a critical enabling capability to modern Army and Navy operations. For this reason, the new doctrine appropriately stresses the inherent ties between national security space missions and the Joint Force. Nobody wants the other services to think that, with the creation of USSF, they can again neglect space security issues within their branch-specific operations.

The U.S. national security space community has made great progress over the past year in reorganizing its main structures, aligning forces to missions, supporting civil and commercial space partnerships, and so far, providing adequate budgetary support for new capabilities and missions.

The next U.S. administration should undertake a comprehensive roles and missions review to assess the implications and effects of the recent reorganizations as well as novel space capabilities.

The latter may make it preferable to have some terrestrial platforms, such as long-flying UAVs, more extensively support space missions; possibly extend some existing air and ground mission areas into the space domain; synchronize better the ground, cyber, and space-based military space assets; consolidate the civilian decision making authority for national security space issues that are presently disaggregated within the Defense Department; and encourage better requirements development coordination between the COCOMs and the intelligence community.

U.S. space decision makers should also continue to build international space partnerships.

The Spacepower capstone document identifies several lines of effort toward this end.

One line calls on the Pentagon to integrate allies and partners better into its plans, exercises, operations, engagements, and intelligence activities, such as the Combined Space Operations initiative among Australia, Canada, France, Germany, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

According to one expert, Sarah Mineiro, “the United States still has a way to go in fully integrating these partners into its space operations centers and in standardizing their access to both intelligence and operational data derived from space.”

Mineiro also sees unrealized opportunities for cooperation with emerging space powers such as Brazil, South Korea, or the United Arab Emirates.

Another line of effort identified in the Spacepower capstone document is to encourage key U.S. allies and partners to develop their own military space capabilities further while cooperating to ensure they enjoy high interoperability with the U.S. national security space enterprise.

One way to do so is through expanding international cooperative research, development, and acquisition efforts for civil, commercial, and military space capabilities.

The Spacepower document also proposes a State Department-led campaign to mobilize international coalitions to shape the strategic space environment by publicizing threats and coordinating messages.

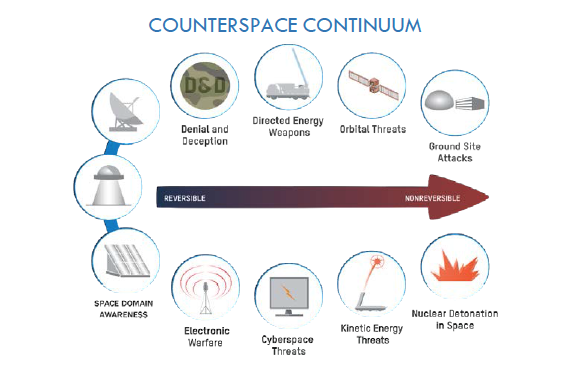

In particular, this campaign would promote less confrontational space norms and standards of behavior by potential adversaries like Russia and China, which have been developing and testing a range of potential counterspace weapons in recent years.

2020_DEFENSE_SPACE_STRATEGY_SUMMARY