The Gray Zone is Not Just an Away Game: We Are In Risk of “Losing Without Fighting”

During my most recent visit to Australia, a key focus was upon the challenge of dealing with the recovery of a more secure infrastructure by our societies in the face of the successful navigation of globalization by the 21st century authoritarian capitalist states.

Air Vice-Marshal (Retired) John Blackburn has been focused on this challenge with regard to Australia in terms of energy security, maritime trade security and recently, following the pioneering work of Rosemary Gibson, on the challenges of a China-dominated pharmaceutical supply chain.

In a recent interview, we discussed these challenges, and how to deal with them, now that authoritarian governments are shaping globalization to their benefit. There is a need to shape more resilient manufacturing and supply chains among the liberal democracies.

According to Blackburn: “Whilst many Defence writers proclaim the aim of “winning without fighting,” we are much more likely to end up “losing without fighting” if we do not get serious about our supply chain vulnerabilities and related issues.”

“We are seeing increased dependencies on foreign-owned energy, pharmaceutical and shipping companies.

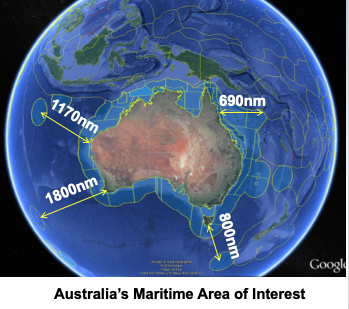

“For example, Australia imports over 90% of its’ transport fuels and transports this on foreign-owned ships. Whilst maritime shipping is crucial to Australia, there are surprisingly only four Australian-flagged merchant ships in the major international trade fleet according to an Australian Government Report; they are all LNG carriers.

“The critical issue that Australians need to consider is what components of critical supply chains are owned or controlled by authoritarian powers.”

This clearly means that there is a need for a much broader security concept than simply preparing for high end kinetic warfare or engaging at distance from our nations in “gray zone areas.”

Trade and manufacturing vulnerabilities in our societies are reshaping the liberal democracies to be the “gray zones” when it comes to being vulnerable to deliberate disruptions in times of crisis.

As Blackburn has put it to military colleagues: “Imagine you are protecting your house. You reinforce the front door. You have a powerful rifle to deter anyone from attacking your house. Unfortunately, while you are focused on the front of your house, you have left the back door open and your adversary is already inside your house and also has control of parts of your critical infrastructure and supply chains.”

“With regard to the cyber threat, some adversaries have clearly already been inside our house. Some may now control significant parts of our gas and electrical supply chains. They may also have control over parts of our medicine supply chain.

“It does not matter how many bars you have on your windows, or how powerful your weapons are if an adversary has already out maneuvered you because of our Government’s faith in market forces to provide security for critical supply chains such as fuels.”

“In Australia, the Government relies on market forces to deliver critical supplies such as fuels. As a result of this approach we are, in my view, in danger of losing without fighting.

“We need a policy and regulatory framework that recognizes that with 21st century authoritarian capitalist powers molding the global trade system and with the ability to direct disruptions for tactical and strategic benefit, the game has changed.

“We may be outmaneuvered before we ever get a chance to fight, because we will not be able to use those fighting elements without assured supply chains.”

To put it bluntly, our security task has become much broader than preparing for the away game; it is recognizing that the liberal democracies are actually living in the gray zone.

In Blackburn’s view, “We need to stop congratulating ourselves for acquiring the latest 5th Gen platform and understand that our security cannot be guaranteed merely by pledging to expend 2% of our GDP on Defence. “

“We need a comprehensive National Security Strategy that acknowledges the world has changes.

“The fact that Australia does not have a National Security Strategy in 2019 is astounding.

“We are at risk of losing without fighting.”

Featured below is an interview with Blackburn conducted at the recent Seapower Conference held in Sydney, Australia during the first week of October 2019, where he focused on the maritime security challenge associated with the danger of “losing without fighting.”

And at the most recent Williams Foundation seminar on shaping a fifth generation integrated force, Brendan Sargeant raised similar concerns to those which Blackburn has in this interview:

We are now moving into a strategic order where that protection may not necessarily be there on the terms that we have been accustomed to. This is a profound change. It means we have to think very differently about our strategic culture and the defence challenge.

I want to describe some features of this change.

Often when we talk about the justification for having a defence force, we speak in terms of being able to exercise sovereignty, to be able to support our national interest through the use the armed forces. My own view about defence is that it is toolkit that enables the government to do many things in the world, but when all that is peeled away, it exists to ensure national survival against existential threats. It is the final guarantor of the state’s sovereignty.

We are in a world where no country is fully sovereign – partial sovereignty is the new normal. I recognise in saying this, that this has always been a reality, but I think the situation is different now because we can’t offset that partial sovereignty with the security that was provided by the rules-based order guaranteed by the United States, and the model of globalisation that it supported.

From another perspective, globalisation underpinned by the rules-based order allowed us to trade sovereignty for security – or to express it another way, it enabled us to accept levels of strategic risk which are now starting to look unacceptable.

So, what does the emerging world look like? Some propositions:

- we are seeing the emergence of new models of globalisation. Some elements include the rise of authoritarian powers underpinned by capitalist economies who are prepared to develop arrangements of convenience to advance their strategic interests and to weaken the authority to and capability of the liberal democracies;

- increasing nationalisms, some with malign impacts;

- weakening consensus on how the international economic order should be managed and governed;

- the weakening of institutions of global governance, and the de-legitimisation of the underpinning legal frameworks that support them;

- less consensus on what the global problem set is (eg. the climate change wars);

- less appetite for global solutions and a strong emphasis on local, bilateral, or regional based solutions to problems;

- declining capacity to manage major transnational problems – eg. people movements;

- massive disruption through the proliferation of new technologies and social media.

This adds up to a world where the global system is less favourable to our national interests and we have less capacity to influence the development of solutions to problems that impinge on our interests.

From the perspective that I have been discussing, the major feature of the emerging global environment is that it increases, rather than reduces, the risk to our security. And part of that risk is in how the emerging system actually operates. For example, can we assume that in a crisis we will have the same access to we currently enjoy to global supply chains?

So the question is: in a world where partial sovereignty is the norm, where we can no longer trade sovereignty for security with the same confidence that we have done so in the past, where global or transnational institutions and conventions are weakening, and where the rules that guided decision making are either diminishing in authority or being discarded, how do we achieve security?

To frame the question another way is: how do we mitigate the risk that partial sovereignty creates in a world with a global system does not deliver security benefits that it used to? How do we build and manage defence capability in this context?

We are not the only country with this challenge.

If we look at the defence challenge through this lens, we can see that some of the assumptions that underpinned defence policy and planning are no longer as robust as they might have seemed. Some implications include:

- that global supply chains will continue to deliver what we need during a crisis;

- that we can assume privileged access to technology and war stocks through the operation of the alliance system;

- we don’t need to stockpile fuel in Australia because of our confidence that the global system would continue to provide supply during a crisis;

- We could continue with a boutique defence industry and just in time logistics systems which are an outreach of larger global systems into which they are integrated.

The world allowed this – in fact, the way the world worked created positive incentives to maximise efficiency through the development of interdependence with external suppliers confident that the rules-based order would continue as we had known it.

For a report on this recent Williams Foundation seminar, please see the following:

The definition by Air Commodore Gordon of the Air Warfare Centre:

“The ability of our forces to dynamically adapt and respond in a contested environment to achieve the desired effect through multiple redundant paths. Remove one vector of attack and we rapidly manoeuvre to bring other capabilities to bear through agile control.”

The Australians are working through how to generate more effective combat and diplomatic capabilities for crafting, building, shaping and operating an integrated force.

And the need for an integrated force built along the lines discussed at the Williams Foundation over the past six years, was highlighted by Vice

Admiral David Johnston, Deputy Chief of the ADF at the recent Chief of the Australian Navy’s Seapower Conference in held in Sydney at the beginning of October:

“It is only by being able to operate an integrated (distributed) force that we can have the kind of mass and scale able to operate with decisive effect in a crisis.”

In short, it is not just about the kinetic capabilities, but the ability to generate political, economic and diplomatic capabilities which could weave capabilities to do environment shaping within which the ADF could make its maximum contribution.

https://sldinfo.com/2019/11/shaping-crafting-building-and-operating-a-fifth-generation-combat-force/