Sustaining the Kill Web with Comprehensive Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance

The need to have more knowledge than the adversary is as old as warfare itself. Well over two-and-a-half millennia ago Sun Tzu said, in The Art of War, “What enables the wise sovereign and the good general to overcome others and achieve things beyond the reach of ordinary men is foreknowledge. Now, this foreknowledge cannot be elicited from ghosts and spirits, nor by analogy with past events nor by deductive calculation. It must be obtained from men who know the enemy situation.”

For centuries, commanders have struggled to collect enough information about the adversary in order to give them the edge in combat. As the Duke of Wellington famously said, “All the business of war is to endeavour to find out what you don’t know by what you do; that’s what I call guessing what’s on the other side of the hill. Another British commander, Admiral Lord Nelson, was victorious at Trafalgar in large part because he used his small, fast ships to scout the position of the French and Spanish fleets.

More contemporaneously, in a naval engagement that marked the turning point of World War II, the Battle of Midway turned on one commander having more of the right information than the other had. U.S. Navy PBY scout planes located the Japanese carriers first, while the Japanese Imperial Navy found the U.S. Navy carriers too late to launch an effective attack. Had Admiral Yamamoto learned the location of his adversary’s carriers just a bit sooner, he might well have been victorious.

Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Precede Every Engagement

Except in those rare instances where two adversaries literally stumble across each other, any wartime engagement is typically preceded by some degree of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) that is, attempting to see, “What is on the other side of the hill.” Throughout the history of warfare, more and more complex (and expensive) platforms have been invented to attempt to locate and obtain information about the enemy. Perhaps in no other area of warfare has technology been so crucial.

Indeed, this is one of the reasons why, in his best-selling book, War Made New, military historian Max Boot noted, “My view is that technology sets the parameters of the possible; it creates the potential for a military revolution.” He supports his thesis with historical examples to show how technological-driven “Revolutions in Military Affairs” have transformed warfare and altered the course of history. And with the exception of inventions such as gunpowder, platforms, systems and sensors optimized for the ISR missions have been some of the most disruptive military technologies.

But effective ISR comes at a cost—and often a substantial cost. Whether it was the ships Admiral Lord Nelson sent out ahead of the force, scout planes in World Wars I and II, modern patrol aircraft such as the P-8 Poseidon, stealthy submarines, state-of-the-art satellites or other means, cost is typically the limiting factor in obtaining a sufficient, let alone comprehensive, degree of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.

One of the most important reasons for the high cost of ISR is simply because, until recently, all of these platforms were manned by military people. For example, the typical mission profile for the P-8 Poseidon, an aircraft whose multiple missions includes ISR, requires a crew of seven highly trained aviation personnel. This is one reason why the U.S. Navy is moving smartly into employing unmanned systems for a number of missions, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance being among the most prominent.

The United States Navy’s Commitment to Unmanned Systems

The U.S. Navy has a rich history of unmanned systems (UxS) development. During the early years of the last century the Navy and the Army worked together to attempt to develop unmanned aerial torpedoes. However this was a bridge-too-far given the state of technology during those years, and the project was ultimately abandoned. Other attempts to introduce unmanned systems into the Navy and Marine Corps occurred in fits and starts throughout the last century, but these met with limited success.

By the turn of the century, the technology to control unmanned systems had finally matured to the point that the U.S. Navy believed it could successfully field unmanned systems in all domains—air, surface, and subsurface—to meet a wide variety of operational needs. As with many disruptive and innovative ideas, the Chief of Naval Operations Strategic Studies Group was tasked to attempt to determine the feasibility of introducing unmanned systems into the Navy inventory. The Group’s conclusion: The Navy should rapidly embrace the use of unmanned systems.

The U.S. Navy’s commitment to—and dependence on—unmanned systems is seen in the Navy’s official Force Structure Assessment, as well as in a series of “Future Fleet Architecture Studies.” Indeed, these reports highlight the fact that the attributes that unmanned systems can bring to the U.S. Navy fleet circa 2030 and beyond have the potential to be truly transformational. Most recently, Advantage at Sea, America’s new maritime strategy, continued the drumbeat regarding the importance of unmanned systems to the Sea Services.

Two decades of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan accelerated the development of unmanned aerial systems (UAVs) and unmanned ground systems (UGVs). More recently, the Department of the Navy has begun to provide increased support for unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), and has established program guidance for many of these systems of importance to the Navy and Marine Corps. This programmatic commitment is reflected in the Navy Program Guide as well as in the Marine Corps Concepts and Programs document. Both show a commitment to a variety of unmanned systems programs.

A Focus on Unmanned Surface Vehicles

Like all unmanned systems, unmanned surface vehicles hold the promise to be critical assets in all scenarios across the spectrum of conflict, especially against high-end adversaries. Unmanned surface vehicles enable warfighters to gain access to areas where the risk to manned platforms is unacceptably high due to a plethora of enemy systems designed to deny access: from integrated air defense systems, to surface ships and submarines, to long-range ballistic and cruise missiles, to a wide range of other systems. These unmanned surface vehicles can provide greater range and persistence on station, leading to enhanced situational awareness of an objective area. Indeed, in a high-end fight, unmanned surface vehicles can be viewed as expendable assets once they perform their mission.

Unmanned surface vehicles are especially adept at conducting the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance mission, and are typically better suited for this mission than their unmanned aerial vehicle counterparts for a number of reasons, particularly their ability to remain undetected by enemy sensors, as well as their dwell time on station. By performing near-shore intelligence preparation of the battlespace (IPB), unmanned surface vehicles increase the standoff, reach, and distributed lethality of the manned platforms they support. As the unmanned option of choice, the USV, or multiple USVs operating together, can gain vital and necessary intelligence information without putting a Sailor or Marine in harm’s way.

The importance of using unmanned systems in the ISR and IPB roles was emphasized by the deputy assistant secretary of the Navy for research, development, test and evaluation, Mr. William Bray, in an interview with U.S. Naval Institute News where he said:

Responding to a threat today means using unmanned systems to collect data and then delivering that information to surface ships, submarines, and aircraft. The challenge is delivering this data quickly and in formats allowing for quick action.

The need to know “what’s on the other side of the hill,” is especially acute for the Navy and Marine Corps in the area of amphibious assault. The prospect of assaulting a heavily defended beach without knowing as much as possible about adversary forces and obstacles courts disaster. For this reason, Navy and Marine Corps officials invited an unmanned surface vehicle manufacturer, Maritime Tactical Systems, Inc. (MARTAC), to field its MANTAS USV as part of several exercises, experiments and demonstrations in order to evaluate its ability to support the ISR and IPB missions during an amphibious assault. This proof of concept was a resounding success.

An Emphasis on Expeditionary Warfare and Amphibious Assault

There are few missions more hazardous to the Navy-Marine Corps team than putting troops ashore in the face of a prepared enemy force. For the amphibious assault mission, UAVs are useful—but are vulnerable to enemy air defenses. UUVs are useful as well, but the underwater medium makes control of these assets at distance problematic. For these reasons, the expeditionary assault force has focused on evaluating unmanned surface vehicles to add to their “kit” to conduct critical ISR and IPB missions.

The Ship-to-Shore Maneuver Exploration and Experimentation (S2ME2) Advanced Naval Technology Exercise (ANTX) (S2ME2 ANTX) provided an opportunity to demonstrate innovative technology that could be used to address gaps in capabilities for naval expeditionary strike groups. S2ME2 ANTX had a focus on unmanned surface systems that could provide real-time ISR and IPB of the battlespace.

During the assault phase of S2ME2 ANTX, the expeditionary commander used a USV to thwart enemy defenses. The amphibious forces operated an eight-foot MANTAS USV which swam into the enemy harbor (the Del Mar Boat Basin on the Southern California coast), and relayed information to the amphibious force command center using its TASKER C2 system. Once this ISR mission was complete, the MANTAS USV was driven near the surf zone to provide IPB on obstacle location, beach gradient, water conditions and other information crucial to planners.

S2ME2 ANTX was a precursor to Bold Alligator, the annual U.S. Fleet Forces Command (USFFC) and U.S. Marine Corps Forces Command (MARFORCOM) expeditionary exercise. Bold Alligator was focused on conducting amphibious operations, as well as evaluating new technologies that support the expeditionary force. The early phases of Bold Alligator were dedicated to long-range reconnaissance. Operators at the exercise command center at Naval Station Norfolk drove the six-foot and 12-foot MANTAS USVs off North and South Onslow Beaches in North Carolina, as well as up and into the Intracoastal Waterway. Both MANTAS USVs streamed live, high-resolution video and sonar images to the command center.

MANTAS performed well in these exercises, experiments and demonstrations and the efficacy of using unmanned surface vehicles to perform the pre-assault ISR and IPB missions while not only keeping Sailors and Marines out of harm’s way, but allowing those Sailors and Marines to be utilized elsewhere (force multiplication) is something Navy and Marine Corps officials are keen to insert into future events. The reasons are abundantly clear as an article in Defense Daily put it:

The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) this week said the unmanned vessels planned in the Navy’s new future fleet plan will help fill in gaps in intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and targeting (ISR&T) in a larger more distributed fleet. “With a more distributed force, we’re going to potentially come at the adversary across a bunch of different vectors and we’re assuming the adversary is going to continue to grow in numbers.” Gilday said the Navy will require a high degree of organic ISR. “And so it’s a gap that is going to continue to widen unless, I think, we move heavier in the direction of unmanned and rely more on unmanned for many of those functions.”

As the Chief of Naval Operations comments make clear, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (and targeting) is a critical factor in the success of all naval missions, and one that is fraught with danger when dealing with peer competitors. Using the advanced technology of unmanned surface platforms to perform this mission and keep operators out of harm’s way is an important capability to continue to develop and field.

More recently, this theme has reinforced by the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General David Berger. In his remarks at the 2021 NDIA Expeditionary Warfare Conference, General Berger put a strong emphasis on ISR and IPB when he noted, “We have to defeat their [enemy] sensors by revitalizing reconnaissance and counter-reconnaissance.”

The Commandant made the most expansive remarks about unmanned systems, noting: “I am a believer in manned-unmanned teaming…We must seek the affordable and plentiful, not the elegant and the few…We need to accelerate our use of unmanned systems and USVs…We need to move forward with unmanned systems at an “uncomfortable rate.”

A Future Focus for the Navy and Marine Corps

As a major step forward in the effort to provide more comprehensive ISR and IPB for Navy and Marine Corps operations, Department of the Navy officials have encouraged the MANTAS USV manufacturer, MARTAC, to scale-up the 12-foot MANTAS used for earlier efforts and produce larger vehicles. This was accomplished last year, and a larger MARTAC Inc. 38-foot DEVIL RAY USV was deployed during the 2020 U.S. Navy Exercise Trident Warrior with positive results. These larger vessels can be used to conduct more extensive ISR and IPB due to their ability to carry considerably more sensors and remain at sea for longer periods. With these larger USVs, the logistics support to expeditionary warfare can greatly increase the ship-to-shore and shore-to-ship missions. Another Force Multiplier.

During his remarks at the 2021 NDIA Expeditionary Warfare Conference, Acting Secretary of the Navy, the Honorable Thomas Harker, discussed “Building Tomorrow’s Navy and Marine Corps.” In his remarks, the Secretary noted, “Autonomous systems are great force multipliers. The Navy’s NAVPLAN and the Marine Corps Force Design both highlight the importance of unmanned systems. We need to integrate Navy and Marine Corps efforts in these areas.”

It is clear that, at all levels, Department of the Navy leaders recognize the importance of unmanned surface vehicles to support Navy and Marine Corps operations, especially in the mission critical areas of ISR and IPB. While the DEVIL RAY USV is only one of several unmanned surface vehicles the Navy and Marine Corps are evaluating, the fact that it is scheduled to be part of a number of exercises, experiments and demonstrations in 2021 is a clear indication that this platform has the form, fit and function to meet Navy and Marine Corps needs today and tomorrow.

Neil Zerbe is a retired Naval Officer with combat experience in carrier-based strike fighters. Neil is also an experienced cruise missile/unmanned systems SME and led multiple unmanned systems and sensors experiments both on active duty and now, as an industry consultant, supporting companies seeking to find the right interested parties in their technology either directly with DoD or another industry partner. Neil helps companies get their new, innovative emerging technologies in front of end-users and helps provide channels to market to expedite solutions to the fleet.

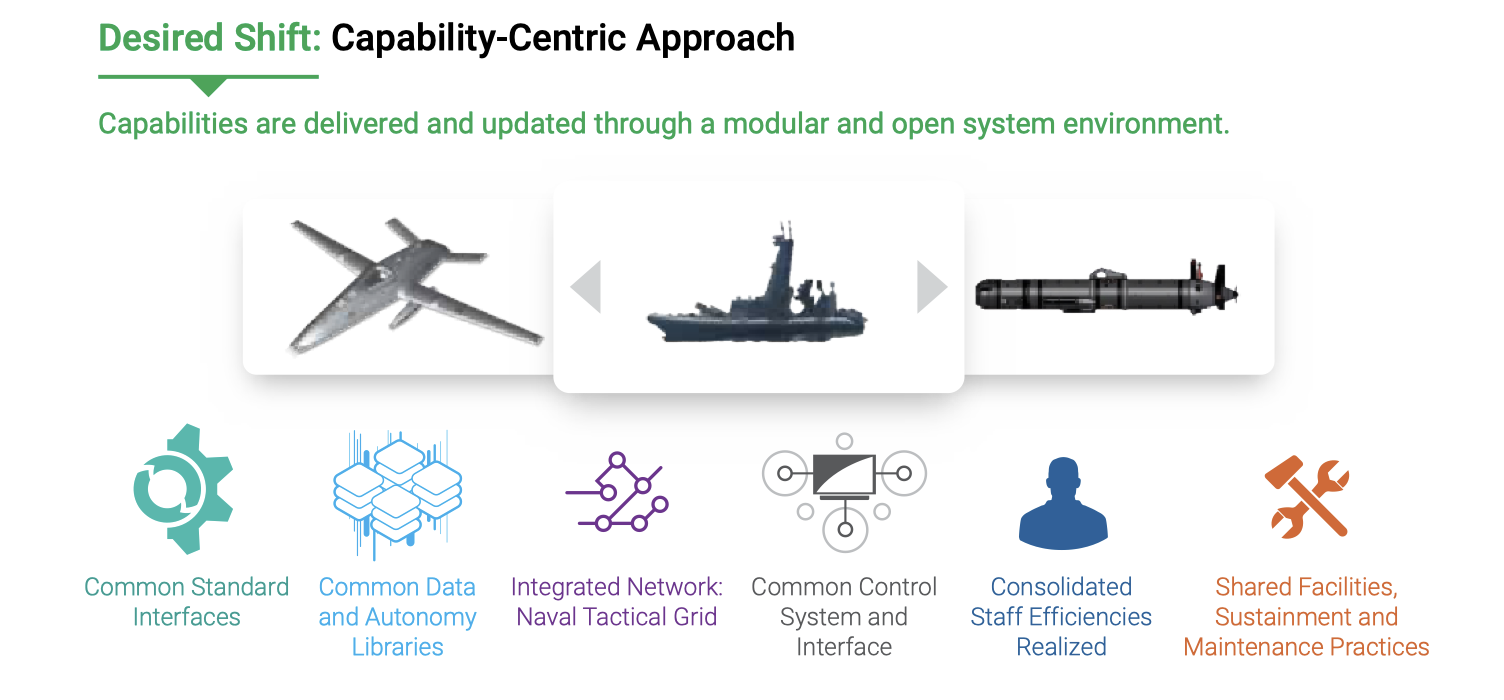

The featured graphic is taken from the recent U.S. Navy’s unmanned campaign plan document, which can be read below:

20210315 Unmanned Campaign_Final_LowRes