Remotely Piloted Aircraft in a Fifth Generation Force

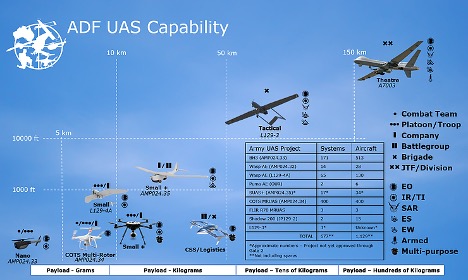

Remote Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) range from micro platforms, such as the in-service Black Hornet, to much larger platforms such as the MQ-4C Triton, with each having a unique range of advantages and limitations which require careful consideration for task application.

Noting the potential tactical, operational and strategic objectives required of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) as outlined in the 2016 Defence White Paper and 2020 Defence Strategic Update, it is unrealistic to expect that one platform can or will provide a holistic ‘one size fits all’ solution.

Fundamental characteristics of air power such as reach, range or manoeuvrability do not apply equally to tasks such as wide-area surveillance or base security. It is, therefore, imperative that each RPAS is tailored to suit the required mission profile.

System architecture is equally important and must be flexible and adaptable to exploit industries’ rapid advancement in a timely fashion.

Small Unmanned Aerial Systems (SUAS) are relatively low cost, highly capable platforms and therefore easily replaceable by newer technologies if structured in a manner which supports rapid spiral upgrades. Technology is advancing at such a rate that SUAS platforms will likely only remain in service for three to five years. Within that time frame, they will likely require yearly spiral upgrades, such as sensor and software improvements to ensure a technological edge is retained.

This concept is echoed by Chris Herd, author of A Brief History of Humanity and the Future of Technologyin which he says ‘we need to stop viewing technology as an existential threat and embrace it in partnership. Technology isn’t our biggest threat; our biggest threat is not embracing it to invent the future.’ Appropriate investment in the right technology will ensure that the ADF sustains a current, capable, and superior RPAS capability.

The Force-in-Being

At present, ADF SUAS utilisation is setting the foundations for the objective and future force. As illustrated below, SUAS range in capability, resulting in potential applications across the tactical, operational, and strategic environments. Their applications can shape and enhance the conduct of everyday tasks while also creating cost efficiencies across Defence.

Take, for example, a SUAS coupled with pixel analysis software, which can be utilised to conduct visual inspections of aircraft to detect damage. This application promises to minimise the human requirement to work from heights generates time and resource efficiencies and increases accuracy. Further, the financial outlay required to obtain such a system is minimal when compared to the force-multiplying capability it provides.

Like all new technology, the introduction of SUAS is not without issue. Any implementation of such a capability requires due diligence, trials and adequate investment in both resources and manning.

If the ADF does not adequately invest in resources and manning, the sustainability of these systems and the ADF’s position as a leader in technological advancement will be jeopardised.

As stated in an Air Power Development Centre Bulletin, the SUAS ‘capability needs to be carefully analysed if the full capabilities of these versatile vehicles are to be realised.’

Successful implementation of SUAS in mainstream Air Force is necessary to create the foundations for a positive narrative; both internal to Air Force, and outwardly to the public. An Internal positive narrative aids in increasing workforce literacy and understanding of unmanned systems, while a positive narrative in the general public highlights the benefits of RPAS and their role within Defence, as well as avoiding inaccurate clickbait headlines such as, ‘ADF buys remote killer drones’.

Resource considerations

During a three year test and evaluation period of the Multi-Rotor Unmanned Aerial System (MRUAS) concept, it became evident that the unit establishment would require review and variation in order to ensure dedicated staff allocation to implement, manage and deliver an enduring UAS capability. Only when units are adequately resourced do, UAS capabilities provide force multiplication opportunities through the creation of time and cost efficiencies, as well as a reduction of safety risks. Efficiencies are lost without suitably experienced and trained personnel to enable the successful implementation and execution.

Expecting existing personnel to take on extensive UAS secondary duties in addition to daily roles and responsibilities is setting the capability up for failure and creating a negative narrative. In a highly active and task-driven Air Force, this expectation is not feasible or sustainable. A dedicated workforce structure has been successfully implemented within the Australian Army and Royal Australian Navy, enabling key fundamental inputs to capability, including engineering, maintenance, training, operations, and supply to occur.

These models must be emulated in an Air Force UAS structure to ensure ADF wide standardisation and training, capability, mission worthiness and future platform procurement. Air Force Strategy dictates that ‘Air Force must build on the experience and knowledge gained with its current platforms and systems to help inform future force-design decisions. This includes the greater use of unmanned systems.’

Capability Considerations In the context of innovation and capability development, understanding the Fourth Industrial Revolution is a key for the ADF. Brendan Marr, Futurist author, explains:

The Fourth Industrial Revolution describes the exponential changes to the way we live, work and relate to one another due to the adoption of cyber-physical systems, the Internet of Things and the Internet of Systems. As we implement smart technologies in our factories and workplaces, connected machines will interact, visualise the entire production chain and make decisions autonomously.

The fourth industrial revolution has already had a significant impact on the ADF, particularly within the ongoing development and employment of unmanned systems and capabilities. Investment in new technologies and concepts must continue for the ADF to remain at the cutting edge of technology. This sentiment is further echoed by Klaus Schwab, Engineer, Economist and founder of the World Economic Forum when he highlights that ‘the scale, scope and complexity of how technological revolution influences our behaviour and way of living will be unlike anything humankind has experienced.’

To ensure Air Force remains in lock step with the fourth industrial revolution, UAS capabilities need to be trialled and implemented within short time frames such that the current and most relevant technologies are exploited.

In doing so, the chain of command must be willing to accept a higher level of risk for capability failure in order to enable progress.

Trials must also consider exploiting opportunities to better understand ADF collection of big data, artificial intelligence (AI) and automation thus driving further efficiencies and building greater corporate knowledge.

Objective Force (3-5 years from present)

Human-in-the-loop (HIL) systems are currently being implemented effectively within semi-autonomous capabilities across the ADF. For example, the Expeditionary Tactical Automated Security System works to autonomously identify potential ground-based threats and is playing an integral role in ISR and increasing security-in-depth. These interactions currently place a high level of importance on the human as a critical decision-maker throughout the mission profile. This raises the question – what does this concept look like without direct human involvement? Moreover, more importantly, what resources and training are required to ensure its success?

As the ADF continues to explore the use of autonomous vehicles and SUAS technology to enhance the force-in-being, the evolution of these capabilities and technologies over the next three years must be examined.

What foundational infrastructure does the ADF need to invest in to support the future force?

While end-user components of SUAS may have a limited shelf life (approximately three to five), critical investments in IT and airbase infrastructure will provide longevity in support of both current and future capability.

One such concept which has the potential to provide a strong return on investment is the utilisation of semi-autonomous vehicles within the objective force. Semi-autonomous vehicles may be used to conduct simple everyday tasks across an airbase at all levels of operation, allowing for increased efficiencies throughout.

Conducting ISR of an airbase is imperative to ensuring security and freedom of manoeuvre of friendly force operations.

Airbase force protection measures ensure the protection of infrastructure, aircraft, and personnel. Using UAS instead of traditional human methods provides a wider aperture of awareness and an ability to react to threats more quickly with greater situational awareness. UAS mission profiles will continue to evolve as testing with an increased scope towards full autonomy develops.

Instead of a security force conducting a perimeter patrol, runway sweep or checking base infrastructure, a UAS or Unmanned Ground Vehicle (UGV) could be tasked to simultaneously achieve these collection requirements in one flight or mission, many times each day. In doing so, the UAS and UGV optimise human resources for employment at the right place, and the right time. This task could be further enabled by an increased application of AI which may enable machines to make decisions and reduce human input during simple tasks.

Training

Parallel to developing foundational infrastructure, the ADF should consider a joint centre of excellence in order to optimise efficiencies. Currently, Army has successfully adopted 20 Surveillance and Target Acquisition (20STA) Regiment as their centre of excellence, while the Navy has chosen 822 Squadron within their Fleet Air Arm.

While each service would continue to champion their individual mission Concept of Operations (CONOPs), developing a joint centre would better highlight opportunities for efficiencies in innovation, Australian industry engagement, capability implementation and funding.

In addition to the creation of a joint centre of excellence, a whole of Government approach to the development of AI and autonomous vehicles would prove valuable. Such an establishment would endeavour to share knowledge in areas such as concept development, research, training, procurement, policy and procedures and technical support. Mechanisms for direct access to Australian industry would further ensure effective ADF access to cutting-edge technologies for joint and interagency use.

Moving forward, the Air Force must acknowledge and learn from the current systems and processes that have been developed by the Army. In 2018, the Army released the Robotic & Autonomous Systems Strategy(RAS) which explores and promotes concept development and the potential of robotics in a Defence setting. An Air Force UAS strategy should similarly be implemented to ensure that the full potential of the system is exploited.

Sergeant William Gill is an Airfield Defence Guard in the Royal Australian Air Force.

He has extensive and diverse operational experience including service on Operations FIJI ASSIST, SLIPPER and MAZURKA.

Sergeant Gill is passionate about Small Unmanned Aerial Systems, and how they can deliver enhanced security effects to national support bases and expeditionary security forces.

In 2020, Sergeant Gill received a Conspicuous Service Cross for his dedicated work in Small Unmanned Aerial Systems.

This article was published by the Central Blue on July 25, 2020.