The Royal Australian Air Force in Bomber Command

Following a week that saw many Australians observe the centenary of the Battle of Hamel and debate the significance of that action, Alan Stephens invites us to consider our views on the unseen Second World War battles in the sky.

Street names at the Australian Defence Force Academy honour notable wartime actions. While every one of those actions was a matter of life or death for the men involved, when measured against the broader sweep of history some scarcely merit the description “battle”. It might seem curious, therefore, that three of the greatest battles in which Australians have fought are not acknowledged.

Those three battles all took place in the skies over Germany during World War II and were fought by the men of the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command, some 11,500 of whom were members of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The first was the Battle of the Ruhr from March to July 1943, the second the Battle of Hamburg from 24 July to 3 August 1943, and the third the Battle of Berlin from November 1943 to March 1944.

Statistics can never tell a story by themselves, but the figures from those three epic clashes reveal a fearful truth. No Bomber Command aircrew who fought in them could expect to survive.

An operational tour on heavy bombers consisted of thirty missions. Crews were then rested for about six months, usually instructing at a training unit. (That “rest” was, however, in name only, as more than 8000 men were killed in flying accidents at bomber conversion units.) They might then volunteer for or be assigned to a second operational tour of twenty missions. Over the course of the war the odds of surviving a first tour were exactly one-in-two – the classic toss of a coin. When the second tour was added the odds slipped further, to one-in-three. And during the battles of the Ruhr, Hamburg, and Berlin the figures became even more terrible, with the loss rates for each mission flown averaging 4.7 per cent, 2.8 per cent and 5.2 per cent respectively, making it statistically impossible to live through thirty missions.

No other sustained campaign in which Australians have ever been involved can compare with the air war over Germany in terms of individual danger. The men of the RAAF who fought for Bomber Command amounted to less than 2 per cent of all Australians who enlisted in World War II, yet the 3486 who died accounted for almost 20 per cent of all deaths in combat. The RAAF’s most distinguished heavy bomber unit, No. 460 Squadron, alone lost 1018 aircrew, meaning that, in effect, the entire squadron was wiped out five times. It was far more dangerous to fight in Bomber Command than in the infantry.

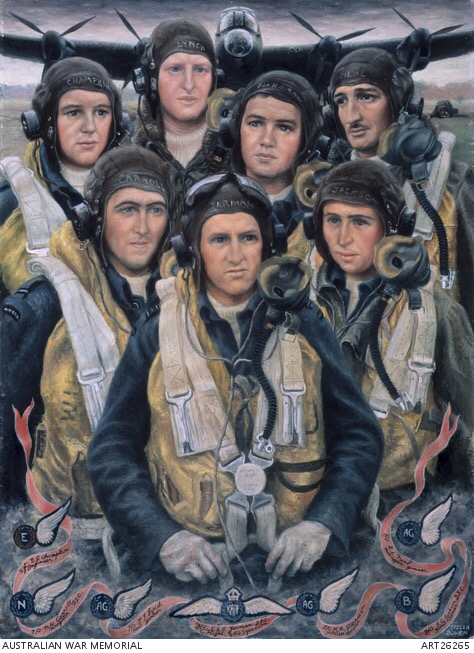

Members of the crew of a Lancaster of No 460 Squadron RAAF on their second tour of operations. [Image credit: Australian War Memorial]

The argument is often made that the bombing of Germany was of limited military utility, and that it stiffened rather than undermined German morale. That argument is stronger in polemic than logic.According to the Nazis’ minister of war production, Albert Speer, following the Hamburg raids he “reported for the first time to the Fuehrer that if these serial attacks continued a rapid end of the war might be the consequence”. And the official United States Strategic Bombing Survey concluded in September 1945 that air power had been “decisive in the war in Western Europe … It brought the [German] economy … to virtual collapse”.

As a direct result of allied bombing, during 1944 the Nazis’ production schedules for tanks, aircraft and trucks were reduced by 35 per cent, 31 per cent and 42 per cent respectively. Additionally, an enormous amount of resources which might have been used to equip front-line troops had to be diverted to air defence. By 1944 the anti-aircraft system was absorbing 20 per cent of all ammunition produced and between half to two-thirds of all radar and signals equipment. More than one million German troops were engaged in the air defence of the Reich, using about 74 per cent of all heavy weapons and 55 per cent of all automatic weapons.

Physical destruction and the massive diversion of resources was accompanied by psychological demoralisation. Contrary to conventional wisdom that the bombing boosted morale, the sustained campaign had a crushing effect on people’s mental state. Post-war surveys found that workers became tired, highly-strung and listless. Absenteeism because of bombing reached 25 per cent in some factories in the Ruhr for the whole of 1944, a rate which drastically reduced output and undermined production schedules. When asked to identify the single most difficult thing they had to cope with during the war, 91 per cent of German civilians nominated bombing.

The men of the RAAF who flew with Bomber Command made the major contribution of any Australians to the defeat of Germany and, therefore, to victory in World War II. They alone opened a second front in Germany, four years before D-Day; and they alone inflicted decisive damage on the German war economy.

As Albert Speer later lamented, Bomber Command’s victory represented “the greatest lost battle on the German side”.

This article first appeared in the June edition of Australian Aviation and draws on Alan Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force: A Centenary History (Oxford University Press: Melbourne, 2001); and Richard Overy, “World War II: The Bombing of Germany”, in Alan Stephens (ed.), The War in the Air 1914-1994 (Air University Press: Maxwell AFB, 2001)

Dr Alan Stephens is a Fellow of the Sir Richard Williams Foundation. He has been a senior lecturer at UNSW Canberra; a visiting fellow at ANU; a visiting fellow at UNSW Canberra; the RAAF historian; an advisor in federal parliament on foreign affairs and defence; and a pilot in the RAAF, where his experience included the command of an operational squadron and a tour in Vietnam. He has lectured internationally, and his publications have been translated into some twenty languages. He is a graduate of the University of New South Wales, the Australian National University, and the University of New England. Stephens was awarded an OAM in 2008 for his contribution to Australian military history.

The article was republished by Central Blue and is republished with their permission.

It was first published on Central Blue on July 8, 2018.