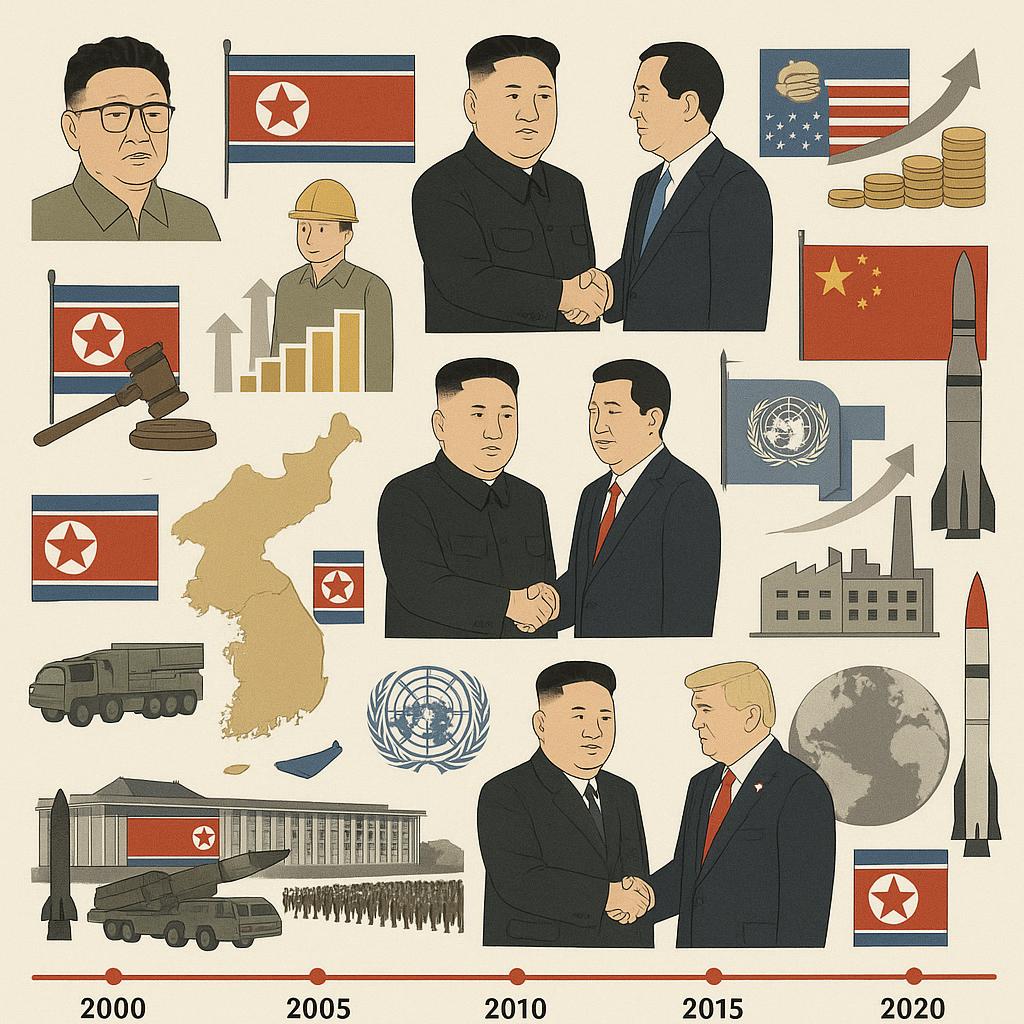

North Korea’s Evolution on the Global Stage: A Significant Player in the Multi-Polar Authoritarian World

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea) has undergone a remarkable transformation in its global positioning over the past two decades.

From a largely isolated pariah state struggling with economic collapse and famine in the early 2000s, North Korea has evolved into a nuclear-armed nation with complex international relationships and a more sophisticated approach to navigating great power competition.

A key tool in shaping their global role is their cyber engagement capabilities and their success in the world of ransomware.

This article examines the key developments in North Korea’s diplomatic relations, military capabilities, economic strategies, and international standing that characterize its evolution on the world stage from 2005 to 2025.

The China Card

For most of the past two decades, China has been North Korea’s primary lifeline and most important relationship. This economic dependence has been a defining feature of North Korea’s international position, even as political relations have fluctuated. Chinese-North Korean trade reached a peak of US$2.78 billion in 2019 before plummeting to US$539 million in 2020 and US$318 million in 2021 due to pandemic-related border closures and restrictions.

The economic relationship remains asymmetric, with North Korea far more dependent on China than the reverse.

Yet this relationship has been characterized by mutual distrust and periodic tensions. As noted by PRC historians Shen Zhihua and Xia Yafeng, portraying the China-North Korea relationship as being “as close as lips and teeth” is a misreading of history, with the relationship marked by significant disagreements dating back to the Korean War.

China’s approach to North Korea has often been driven more by strategic calculations—particularly its desire to prevent regime collapse and refugee flows across its border—than by ideological alignment.

The Russian Card

Perhaps the most significant shift in North Korea’s international positioning has occurred in its relationship with Russia. Following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, cooperation between Moscow and Pyongyang increased dramatically.

This relationship was formalized through a “comprehensive strategic partnership” treaty signed in June 2024 during Russian President Vladimir Putin’s first visit to North Korea in 24 years.

The relationship evolved from primarily transactional to strategic, with North Korea supplying military equipment to Russia beginning in September 2023. According to South Korean intelligence estimates, North Korea had supplied Russia with approximately 20,000 containers of weaponry by October 2024, primarily artillery shells, short-range missiles, and anti-tank missiles.

This cooperation reached unprecedented levels when in October 2024, North Korea deployed approximately 12,000 troops to assist Russian forces in Ukraine, primarily in the Kursk region.5

This direct military involvement represented a watershed moment in North Korea’s foreign policy and signaled a qualitative change in its willingness to project power beyond the Korean Peninsula.

The Dynamic with South Korea

Relations with South Korea have followed a pattern of tension, brief thaws, and renewed hostility. The demilitarized zone (DMZ) continues to divide the peninsula, with anti-communist and anti-North Korea sentiment remaining strong in South Korea.

The period of rapprochement initiated by South Korean President Moon Jae-in in 2018-2019 ultimately failed to produce sustainable improvement in relations.

By 2024, North Korea had explicitly abandoned its unification policy toward South Korea, instead institutionalizing hostility.

This shift was reflected in provocative actions like sending over 1,000 balloons filled with trash into South Korea in June 2024, leading Seoul to suspend its participation in a 2018 joint military agreement.

The relationship reached a new low when North Korea formally designated South Korea as a “hostile state” in its constitution.

Nuclear and Missile Development

North Korea’s military capabilities have expanded dramatically over the past twenty years, with its nuclear and missile programs representing the most significant developments. The country conducted its sixth nuclear weapons test in 2017, claiming to have developed a hydrogen (thermonuclear) bomb. That same year, it successfully tested an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and U.S. intelligence determined North Korea could miniaturize nuclear weapons to fit inside missiles.

This rapid advancement has continued, with North Korea conducting an ICBM test in October 2024 (its first since December 2023) and launching seven short-range ballistic missiles in November 2024. The country has also made significant strides in solid-fuel missile technology, successfully testing its first solid-fuel ICBM, the Hwasong-18, in 2023.

This represents an important technological leap as solid-fuel missiles require less preparation time and are more mobile, making them harder to detect and intercept.

North Korea’s military doctrine has evolved from a primarily defensive posture focused on regime survival to one capable of offensive operations beyond its borders.

While the country’s “military-first” policy (Songun) has been a constant, the nature of its military capabilities has transformed dramatically.

The deployment of North Korean troops to support Russia in Ukraine marks perhaps the most significant shift in decades.

While North Korean troops reportedly do not wear their national uniforms — an apparent attempt to maintain a veneer of deniability — this direct military engagement in a foreign conflict represents a radical departure from previous policies.

The North Korean Economic Approach

North Korea’s economic approach continues to be shaped by its ideology of Juche (self-reliance) operating in an environment of international sanctions.

The economy remains dominated by state-owned industries and collective farms, though foreign investment and a degree of corporate autonomy have increased over time.

The North Korean economy has shown surprising resilience despite international isolation. For the first time, in 2021, South Korea’s Ministry of Unification estimated that North Korea’s private sector had outgrown its public sector until 2020, suggesting significant internal economic changes despite the appearance of continuity.

Under Kim Jong-un, who assumed power in December 2011, North Korea has experienced periods of both economic liberalization and recentralization. Initially, the regime tolerated and even encouraged the expansion of private markets as a source of tax revenue.

However, following the failure of the Hanoi Summit with the United States in February 2019, the government began reasserting centralized control over the economy.

This recentralization accelerated with the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when North Korea implemented some of the world’s strictest border controls. By January 2021, the regime had officially reclaimed control over all foreign trade and domestic markets.

The new five-year economic plan (2021-2025) announced at the 8th Party Congress stressed centralized management across all sectors and advocated greater political control in day-to-day economic planning.

Despite its ideological commitment to self-reliance, North Korea has experimented with special economic zones designed to attract foreign investment while maintaining political control. The Rason Special Economic Zone was established in the early 1990s in the northeastern corner of the country bordering China and Russia.

The country designated over a dozen new special economic zones between 2013 and 2014, though the success of these zones has been limited by international sanctions and North Korea’s own restrictions.

More recently, North Korea has shown renewed interest in developing its tourism industry. After limited opening to Russian and Chinese tourists in 2024, 2025 is expected to be “the year the country is fully back in the tourism business.”

Before the pandemic, Chinese tourists represented over 90% of foreign visitors to North Korea, and the country hopes to revive this sector, with plans to open a major tourism site on its east coast in June 2025.

Work Arounds with Regard to Western Sanctions

Despite extensive sanctions, North Korea has developed sophisticated methods to generate revenue through foreign-based workers, state-owned enterprises, and illicit activities. These revenues have been crucial for funding the country’s weapons programs and supporting the elite.

The U.S. Treasury Department has identified numerous individuals and entities involved in North Korea’s sanctions evasion efforts.

For example, in December 2024, the U.S. imposed sanctions on North Korean banks, military officials, and Russian companies shipping oil and gas to North Korea in violation of UN resolutions. According to U.S. officials, North Korean IT workers operating in countries like Russia and Laos have been a significant source of foreign currency earnings that support the regime’s weapons programs.

One of North Korea’s most successful adaptations has been its ability to exploit tensions between major powers to advance its own interests.

The growing strategic competition between the United States and China, as well as between the West and Russia, has created openings for North Korea to reduce its isolation and strengthen its position.

In March 2024, Russia surprisingly vetoed — and China abstained from voting on—a UN resolution calling for the extension of the mandate of the UN Panel of Experts responsible for monitoring North Korea’s sanctions violations.

This effectively weakened the international sanctions regime against North Korea, demonstrating how great power competition has undermined previously united international efforts to constrain North Korea’s weapons programs.

Moving Forward

North Korea entered 2025 in a stronger position than it occupied at the start of 2024, benefiting from its revived alliance with Russia, a workable relationship with China, and weakened international sanctions.

The country is implementing a “Regional Development 20×10 Policy” focused on economic development while continuing to strengthen its military capabilities.

The North Korea-Russia partnership has catalyzed what some analysts describe as a “fundamental change” in both the geopolitical landscape of Northeast Asia and the broader international order.21 This realignment poses new challenges for the United States and its regional allies, particularly South Korea and Japan, which now face the prospect of coordinated actions between North Korea and Russia.

As North Korea looks toward the future, several trends are likely to shape its evolution:

- Military Modernization: Despite economic challenges, North Korea continues to prioritize military development, particularly its nuclear and missile programs. Technical cooperation with Russia in areas such as space vehicles, aircraft, anti-air missile systems, and unmanned aerial vehicles is likely to accelerate this process.

- Economic Pragmatism: While maintaining its ideological commitment to self-reliance, North Korea is showing signs of economic pragmatism. The country is seeking to benefit financially from its cooperation with Russia while also gradually reopening to limited foreign tourism and trade.

- Strategic Flexibility: North Korea has demonstrated remarkable strategic adaptability over the past two decades. Historically “North Korea has typically been close to either the Soviet Union (and now Russia) or China — not both.” The current alignment with Russia may eventually shift if circumstances change, particularly if the Ukraine conflict ends and Russia reassesses its strategic priorities.

Over the past twenty years, North Korea has evolved from a primarily isolated pariah state with limited capabilities into a nuclear-armed nation with strategic partnerships and a more sophisticated approach to international relations.

While remaining economically challenged and politically isolated from much of the world, North Korea has demonstrated remarkable resilience and strategic adaptability.

The most significant evolution has been North Korea’s transition from a state primarily focused on regime survival to one capable of projecting power beyond its borders — both through its nuclear and missile programs and, more recently, through direct military support to Russia.

This transformation has fundamentally altered the security dynamics of Northeast Asia and presents increasingly complex challenges for the international community.

North Korea is pursuing a dual strategy of military advancement and limited economic development, leveraging its partnerships with Russia and China while maintaining its core ideology of self-reliance and regime preservation.

The success of this strategy will depend on many factors, including the future of great power relations, the economic benefits derived from its Russia partnership, and the regime’s ability to manage internal pressures for reform.

What is clear is that North Korea is no longer simply a regional irritant but has become a significant actor in the global geopolitical landscape — a remarkable evolution for a country of 26 million people that was widely dismissed as a failed state at the beginning of the century.

The featured image was generated by an AI program.

For our look at North Korea within the multi-polar world see our recent book:

The Emergence of the Multi-Polar Authoritarian World: Looking Back from 2024