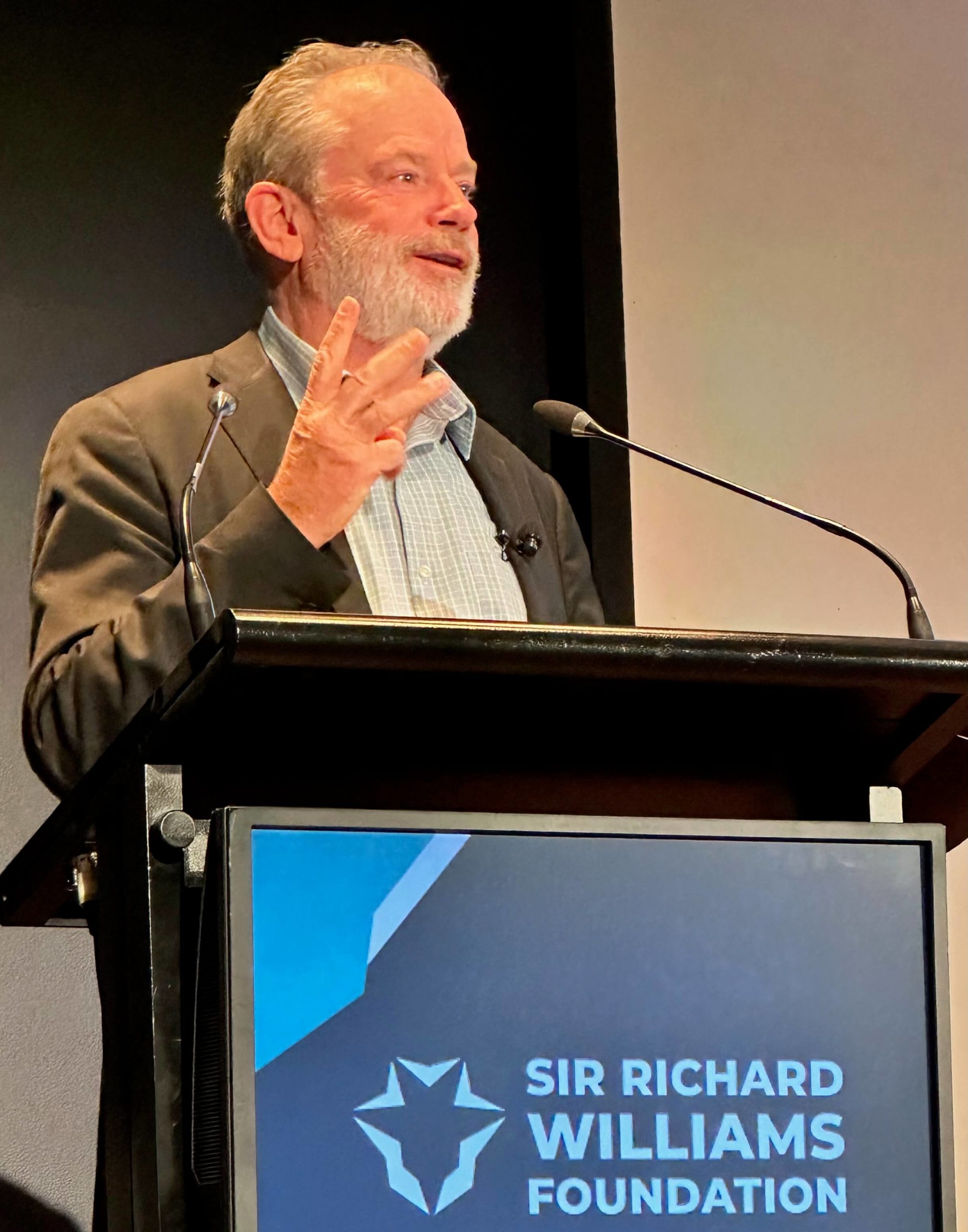

Dr. Marcus Hellyer on Breaking the Autonomous Systems Defence Employment Barrier

On May 22, 2025, I had a chance to talk with Dr. Marcus Hellyer about a key problem which was raised during his presentation yesterday at the Sir Richard Williams Foundation seminar.

Australia faces its most challenging strategic environment since World War II, yet its defense establishment remains locked in outdated thinking that could prove catastrophic in a future conflict. Despite having a $59 billion (AD) defense budget and world-class autonomous systems companies operating in its northern waters, the Australian Defense Force (ADF) continues to treat cutting-edge autonomous systems as experimental curiosities rather than essential warfighting tools.

While defense officials typically cite legal, ethical, and budgetary concerns as barriers to autonomous systems adoption, Hellyer argues these are largely excuses masking deeper cultural problems. “I think those are excuses. Those aren’t real barriers. You can overcome them because people already have around the world,” he observed. “The real issues are cultural. They’re mental barriers.”

The financial argument particularly frustrates defense experts. With $59 billion Australian dollars available annually, the relatively modest investments needed for autonomous systems development pale in comparison to traditional platform costs. The problem isn’t money — it’s mindset.

The fundamental issue lies in applying Cold War-era acquisition thinking to 21st-century technology. Traditional defense platforms like destroyers or fighter jets represent 30-year investments requiring extensive development and testing before deployment. Autonomous systems operate on entirely different principles.

“We have to regard autonomous systems as consumables, not as 30-year investments,” Hellyer emphasized. These systems function more like sophisticated tools with 5-year lifecycles, designed for specific tasks rather than decades of general-purpose service.

This shift demands abandoning the pursuit of perfect requirements before acquisition. Instead of spending years developing ideal specifications, defense forces should deploy systems quickly and learn through operational use. The Ukrainian conflict demonstrates this approach dramatically — their autonomous systems “are nowhere near technological readiness level nine” yet have sunk Russian ships, downed helicopters, and conducted strikes against land targets.

Current defense thinking creates a self-defeating cycle: officials claim they cannot acquire systems without understanding requirements, but requirements can only be understood through actual operational experience. This worked for traditional platforms where single acquisitions represented massive investments, but autonomous systems offer the freedom to experiment and iterate.

“But one can only understand what works and what doesn’t work if you actually have them in service and you give them to your smart young men and women, and then they’re experimenting with them,” Hellyer added.

The key is treating these systems as operational tools rather than experimental projects.

Despite institutional inertia, Australia possesses significant advantages for autonomous systems development. While the nation cannot build F-35 fighters or sophisticated submarines, its industrial base excels in areas directly relevant to autonomous systems: mining support, agriculture, construction, and transportation.

“The Australian industrial base can actually design autonomous systems. It can build autonomous systems. And it wouldn’t be difficult to be able to build them at scale,” Hellyer observed. This capability becomes crucial when considering extended conflicts where access to American-built systems may be limited.

Companies like Ocius already demonstrate this potential, operating autonomous vessels in Australia’s northern waters after overcoming initial bureaucratic resistance. What started as skepticism from harbor authorities has evolved into acceptance of unmanned operations—proof that institutional barriers dissolve once systems prove their value

Australia’s geographic challenges make autonomous systems particularly valuable. Traditional ISR assets cannot simultaneously monitor all approaches through the archipelagic regions to Australia’s north. Autonomous systems can maintain persistent surveillance of multiple strategic chokepoints, ports, and transit lanes while freeing expensive crewed platforms for other missions.

This creates possibilities for layered defense concepts: autonomous systems provide the sensor grid, identify threats, and communicate with crewed platforms for prosecution. Such approaches offer redundancy, reduced signatures, and decentralized command structures—all essential for modern conflict.

While Western defense establishments agonize over autonomous systems ethics, potential adversaries face no such constraints. Authoritarian regimes will deploy whatever works without philosophical hesitation. This reality should inform acquisition strategies, but instead, ethical concerns often become excuses for inaction.

The contrast with Ukrainian innovation is stark. Facing existential threats, Ukrainian forces rapidly adapted commercially available systems for military use through trial and error. Their approach demonstrates that sophisticated defense organizations aren’t necessary for effective autonomous systems employment—adaptability and willingness to experiment matter more than perfect doctrine.

Every month of institutional delay represents lost operational learning and capability development. Unlike traditional platforms requiring years of development, autonomous systems can provide immediate value while continuously improving through operational experience.

More concerning, delay allows adversaries to gain advantages in systems that could prove decisive in future conflicts. The question isn’t whether autonomous systems will transform warfare—Ukraine has already demonstrated that reality. The question is whether Australia will adapt quickly enough to remain strategically relevant.

Overcoming institutional resistance requires acknowledging that autonomous systems represent a fundamental paradigm shift, not merely new platforms within existing frameworks.

This means:

- Treating systems as consumable tools rather than generational investments

- Accepting operational learning over perfect pre-deployment requirements

- Recognizing task-specific design over general-purpose platforms

- Embracing rapid iteration cycles instead of extended development programs

The alternative is continuing current patterns until a strategic shock forces adaptation—potentially too late to maintain strategic advantage.

For Hellyer, Australia’s defense establishment must move beyond treating autonomous systems as experimental curiosities and recognize them as essential capabilities for modern defense. The technology exists, the industrial base can support it, and operational concepts are proven in current conflicts.

What’s missing is institutional courage to abandon comfortable legacy thinking and embrace the autonomous revolution already transforming global security. The choice is clear: adapt now through deliberate action or adapt later under the pressure of strategic crisis. History suggests the latter option rarely ends well.

Note: Technology Readiness Level 9 (TRL 9) in the Australian Defence acquisition system is defined as:

TRL 9: System Proven and Ready for Full Commercial Deployment

Definition: Actual system proven through successful operations in operating environment, and ready for full commercial deployment.

Description: The technology is in its final form and operated under the full range of operating conditions. Examples include steady state 24/7 manufacturing meeting cost, yield, and output targets. Emphasis shifts toward statistical process control.

Context of TRL 9 in Defence Acquisition

TRL 9 represents the highest level of technological maturity in the Defence acquisition system. At this level:

- The technology has completed all development phases

- It has been proven through successful operations in real operating environments

- The system is ready for full-scale deployment and manufacturing

- All technical, engineering, and manufacturing risks have been retired

- The focus shifts to process optimization and quality control

TRLs 7-9 fall within the domain of industry and take promising technologies through to maturity and production, ready for deployment. TRLs are based on a scale from 1 to 9 with 9 being the most mature technology

The TRL system is used by the Australian Department of Defence to assess and communicate technology maturity consistently across different acquisition programs, helping to manage risk and make informed decisions about capability development and procurement.

See also, my latest book and the discussion in the podcast generated discussing the book:

A Paradigm Shift in Maritime Operations: Autonomous Systems and Their Impact