The Evolution of Fighter Pilot Training: Inside Italy’s Advanced M-346 Program

The Italian Air Force’s International Flight Training School (IFTS) represents a fundamental shift in how modern fighter pilots are prepared for combat.

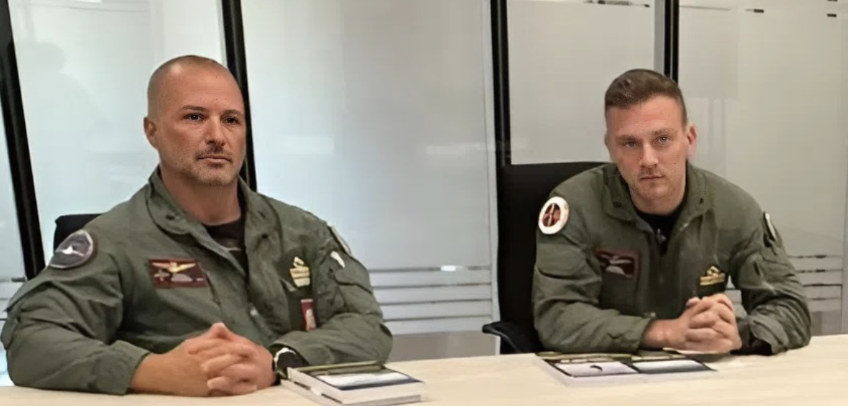

In an interview, with Lt. Col. Marco Gismondi, Squadron Information Officer, and Lt. Gabriel Morarasu during my first day of visits to the school, they discussed how the M-346 advanced jet trainer is being used along with sophisticated simulation, sensor integration, and real-world tactical experience to shape the IFTS approach.

The M-346 embodies a complete reconceptualization of how aviators prepare for modern air combat. At the heart of this transformation lies the Embedded Tactical Training System (ETTS), a sophisticated simulation capability that fundamentally changes what students experience in the air.

“We can simulate pretty much everything,” Gismondi explains, “especially if we work with somebody that talks the same language.” This simulation goes far beyond simple role-playing exercises. When instructors’ brief students on threats like the Su-29 or Su-34, those aren’t just theoretical discussions. In the air, students encounter exactly what they were briefed on. Their fire control radar displays the correct signatures, their electronic warning receivers show the appropriate signals, and their targeting pods display the enemy aircraft exactly as it would appear in actual combat.

This level of fidelity creates an unprecedented training environment. “Everything looks like exactly reality,” Gismondi emphasizes. “What it would look like with the real Su-34 on the other side.” The psychological impact cannot be overstated. Students aren’t training against other M-346s pretending to be threats; they’re training against virtualized but realistic representations of actual adversary aircraft, complete with accurate performance characteristics and sensor signatures.

The distinction is crucial. In traditional aggressor training, students might fly against aircraft that approximate enemy capabilities, but they’re always aware they’re fighting against familiar platforms. With the M-346’s ETTS, students see the real threat, albeit a virtual one, creating muscle memory and decision-making patterns that translate directly to operational flying.

The M-346’s evolution is intrinsically linked to Italy’s F-35 program, though the relationship is more nuanced than simple preparation. While the M-346 cannot establish a data link with the F-35 — “the 346 doesn’t see the F-35 because we are not linked with them” — the fifth-generation fighter’s sensors can track the trainer with ease. This asymmetry has proven valuable, allowing the M-346 to support F-35 exercises by providing realistic adversary representations.

The early days involved Eurofighter Typhoons, where actual data links allowed for more integrated exercises. The M-346 could represent threats with full situational awareness, using its simulated fire control radar and targeting pod to create realistic opposition for fourth-generation fighters. But as the program matured, the capabilities expanded dramatically.

Now, the aircraft is undergoing perhaps its most significant upgrade yet. The new Block 20 configuration will feature large F-35-style touchscreen displays, 6.9 inches, that fundamentally change how students interact with aircraft systems. This isn’t merely about modernization; it’s about cognitive preparation for the cockpit environment students will encounter in operational fighters.

“Many of our pilots are going to the F-35, so they get used before actually stepping into the F-35 how to use that type of avionics,” Gismondi notes. The financial and temporal implications are significant. Students transitioning from older trainers like the MB-339 face a steep learning curve when they encounter modern glass cockpits. By introducing F-35-style interfaces in advanced training, the M-346 compresses that learning curve, allowing students to arrive at operational conversion units already familiar with touchscreen operation, display management, and information architecture.

The displays themselves are configurable for different mission types. Air-to-air missions use different formats than air-to-ground operations, mirroring how operational fighters optimize cockpit displays for specific roles. “If the mission is primarily one of destroying targets, we’re using certain formats,” Gismondi explains. “If it’s primary air-to-air defense or attack, we use a different format in our displays.” This mission-specific customization teaches students not just to fly, but to optimize their cockpit environment for the task at hand which is a critical skill in modern fighters where information management can be as important as stick-and-rudder skills.

Perhaps nowhere is the transformation in fighter aviation more evident than in how the M-346 program approaches formation flying. Traditional military aviation emphasized visual formation, aircraft operating in close proximity, with wingmen maintaining position through direct observation of the lead aircraft. The M-346 program has largely abandoned this paradigm.

“Right now here we’re more focused on sensors formation than visual formation,” Gismondi reveals. The implications are profound. Wingmen are expected to maintain formation not by watching their leader, but by monitoring sensors and displays. “We’re actually fighting virtually at 10 plus miles from each other in many missions, because the sensor allowed you to do so.”

This represents a complete inversion of traditional fighter doctrine. For decades, mutual support meant staying close enough for visual identification and immediate response. Modern sensors and data links have changed the calculus entirely. A wingman 10 miles away can maintain situational awareness on the lead aircraft’s position, heading, speed, and tactical situation through electronic means. The Head-Up Display (HUD) provides constant positional data, while the fire control radar and Horizontal Situation Display (HSD) offer detailed information on range, azimuth, aspect, and engagement status.

For students, this requires a fundamentally different skill set. Success as a wingman is no longer primarily about precise aircraft control to maintain visual formation. Instead, it demands constant information synthesis from multiple sensors, spatial awareness derived from electronic data rather than visual cues, and the ability to operate semi-independently while maintaining team coordination.

“You’re the wingman, meaning that you have not responsibility of this mission, but you actually find your own aircraft by your own,” Gismondi explains. This apparent contradiction, being part of a team while operating independently, defines modern fighter operations. The sensors provide the connectivity that allows distributed operations, but students must develop the judgment to use that connectivity effectively.

Lt. Col. Gismondi’s 25-year flying career provides perspective on perhaps the most significant trend in military aviation: the shift from aircraft operation to tactical employment. His early experience on the T-37 basic trainer with its scattered analog instruments and challenging cross-check patterns contrasts sharply with modern training aircraft. The T-38 that followed, while not complex, was demanding to fly due to its small wings, supersonic profile, and modest power. These aircraft required significant mental capacity just to maintain controlled flight.

“I noticed the trend, which I believe is the right trend, went from the skill to fly the aircraft stick and throttles to the skills to fight,” Gismondi observes. “Aircraft need to be easier than before to allow the brain of a human, normal human being, to focus on tactical side, versus the basics.”

This philosophical shift permeates modern fighter design. The Italian Air Force’s Tornado represented an intermediate step, an old airframe requiring two crew members, with one dedicated primarily to flying and the other to tactical systems operation. The F-35 represents the culmination of this evolution: an aircraft that largely flies itself, freeing the pilot to focus almost entirely on tactical decision-making, sensor management, and mission execution.

The M-346 prepares students for this reality. Rather than emphasizing stick-and-rudder skills, though basic flying proficiency remains essential, the program focuses on decision-making, sensor management, and tactical thinking. Students learn to operate in an information-rich environment where success depends on processing data from multiple sources, prioritizing threats, and making rapid tactical decisions.

Lt. Morarasu’s perspective as a student confirms this transformation. “I’m arriving from phase three on the 339, which was a basic aircraft still doing advanced formation,” he notes. The MB-339, while capable, represents an older generation of training aircraft. The transition to the M-346 wasn’t merely about learning a new aircraft; it was about developing an entirely different operational mindset.

“When we start, we start to know the aircraft, to know to fly the aircraft, and then we start with much more advanced stuff,” Morarasu explains. “I can recognize myself that I’ve learned a lot of new stuff, new ways of thinking, how to manage the aircraft differently.” The emphasis on management rather than control is revealing. Modern fighters aren’t flown so much as directed, with pilots managing complex systems rather than directly manipulating flight controls for every maneuver.

One of the M-346 program’s most innovative aspects is its integration of current intelligence from operational squadrons. Italy’s air policing missions in northern Europe where F-35s and other fighters encounter Russian aircraft provide a constant stream of data about adversary capabilities, tactics, and performance characteristics.

“We’re always encountered with operational squadrons, and we receive not classified information, very useful to build up a credible and reliable syllabus”, Gismondi reveals. This intelligence proves invaluable for realistic training. When F-35s conducting air policing missions discover that an adversary aircraft’s radar has different characteristics than expected, that information flows back to IFTS.

Gismondi provides a specific example: “Let’s play with unclass numbers in order to provide the idea and say that an adversary aircraft has 70 degrees width for the radar, and somehow F-35 realizes, with their sensors, those 70 degrees aren’t correct, it’s more.” The ability to update training scenarios with current intelligence ensures students aren’t training against outdated threat models.

The synthetic environment allows risk-free experimentation with new tactics. “We can try for free. We’re not going to lose anybody, and we realize if they work or not,” Gismondi explains. If intelligence suggests an adversary radar has an 85-degree field of view rather than 70 degrees, instructors can immediately update the simulation and test whether existing tactics remain effective with those modified parameters.

This creates a feedback loop between operational flying and training that would be impossible to achieve with traditional live-flying aggressor programs. Updating a simulation is far simpler and cheaper than modifying actual aircraft or changing adversary tactics. The result is training that remains current with the latest intelligence, preparing students for the actual threats they’ll encounter rather than historical or theoretical ones.

The M-346’s simulation capabilities point toward future possibilities that would have seemed like science fiction just years ago. If the aircraft can simulate adversary fighters with high fidelity, why not friendly unmanned systems as well?

“Since it’s a simulation, and the distance between each aircraft, even on the same side, is growing, why not?” Gismondi muses. “I don’t see any problem or any reason why we cannot implement drones, simulated drones, flying together with the 346.”

The concept is logical. Modern fighter operations increasingly emphasize distributed operations with aircraft separated by significant distances. If the M-346 can train students to operate as a wingman 10 miles from their leader using sensor data alone, extending that paradigm to include unmanned wingmen is a natural evolution.

With the new Block 20 avionics and large touchscreen displays, the M-346 could function as a command and control platform for simulated drones during training missions. Students would learn not just to fly and fight as individuals or traditional formations, but to direct unmanned systems as part of a manned-unmanned team. This capability would prepare pilots for the next generation of air combat, where human fighters increasingly operate alongside autonomous or semi-autonomous systems.

IFTS has evolved into an international center of excellence for advanced jet training. The facility hosts pilots from numerous nations, creating a multinational environment that enriches the training experience while demonstrating Italian Air Force expertise.

“We have SNRs or IPs from Canada, from Norway, there’s U.S. pilots in training,” Gismondi notes. These aren’t just students; experienced fighter pilots from partner nations serve as Senior National Representatives (SNRs), bringing diverse perspectives and expertise that improve the overall program.

The Canadian SNR, for example, is rewriting portions of the Basic Training Manual based on insights from his operational experience. “He noticed that there’s something that could be improved,” Gismondi explains. “Obviously, we’ll talk about it, but it’s up on our level to change that, so it’s fairly easy and flexible to do so.”

This openness to external input reflects confidence in the program while acknowledging that good ideas can come from anywhere. Different air forces have different operational experiences, tactical emphases, and training philosophies. By incorporating the best practices from multiple nations, IFTS creates a training program that exceeds what any single nation might develop in isolation.

The international character also prepares students for coalition operations. Modern military aviation rarely involves single-nation operations; most conflicts see multinational coalitions working together. Training in a multinational environment from the beginning helps pilots develop the communication skills, cultural awareness, and operational flexibility essential for coalition success.

The relationship between the Italian Air Force and Leonardo, the M-346’s manufacturer, exemplifies how effective military-industry partnerships should function. Rather than a traditional vendor-customer relationship, the collaboration is more of an ongoing dialogue where operational requirements drive continuous improvement.

“They give us great support. They try to satisfy us in any possible way,” Gismondi notes. “Everything we ask, they take into account. They may do it immediately, if it’s possible, or they may release it in a further batch.”

This responsive approach ensures the aircraft evolves to meet actual training needs rather than what manufacturers think those needs should be. When instructors identify a capability gap or potential improvement, Leonardo can often implement changes relatively quickly. The flexibility stems partly from the aircraft’s software-defined architecture, where many capabilities can be added or modified through software updates rather than hardware changes.

The upcoming Block 20 upgrade represents a culmination of years of operational experience and feedback. The large touchscreen displays, enhanced simulation capabilities, and other improvements aren’t arbitrary additions; they’re direct responses to identified training requirements based on actual experience with the aircraft.

Lt. Morarasu’s reflections as a current student provided insight into how the M-346 program transforms pilots at the individual level. His progression from the MB-339, a capable but basic trainer, to the M-346 involved far more than just learning a new aircraft type.

“I feel much more independent into the aircraft right now, I feel much more confident with the aircraft,” Morarasu explains. The confidence comes not from mastering complex flying skills, but from learning to manage information, make decisions, and operate semi-autonomously while remaining part of a larger team.

The learning curve is steep but manageable. “We start to know the aircraft, to know to fly the aircraft, and then we start with much more advanced stuff.” The progression is deliberate from basic aircraft familiarization and flying skills first, then increasingly complex tactical scenarios that challenge decision-making and systems management.

“We increase a lot our flexibility, and a lot of the decision-making,” Morarasu notes. This emphasis on flexibility and decision-making reflects the realities of modern air combat, where no two missions are identical and pilots must constantly adapt to changing circumstances. Scripted responses and rote procedures have limited value when facing sophisticated adversaries with their own decision-making capabilities.

The “huge learning curve” Morarasu references isn’t just about accumulating knowledge; it’s about developing a fundamentally different approach to flying. The transition from basic trainers to advanced jets has always involved significant challenges, but the M-346 program adds the complexity of modern sensor management, distributed operations, and tactical decision-making that previous generations encountered only after reaching operational squadrons.

The M-346 program at IFTS represents more than just effective pilot training for it’s a glimpse into the future of military aviation education. By integrating sophisticated simulation, current intelligence, modern sensor packages, and F-35-style displays into an advanced trainer, the Italian Air Force has created a program that prepares students for the realities of modern air combat far more effectively than traditional approaches.

The philosophical shift from flying to fighting, from visual to sensor-based operations, and from individual skill to information management reflects broader changes in military aviation. As aircraft become more capable and complex, pilot training must evolve to focus less on aircraft control and more on tactical decision-making and systems management.

The international character of IFTS demonstrates another important trend: the increasing interconnectedness of allied air forces. Modern air warfare is inherently multinational, and preparing pilots for that reality from the beginning of their advanced training creates more effective coalition operators.

Perhaps most importantly, the M-346 program shows how military-industry partnerships can drive continuous improvement when both parties remain focused on actual operational requirements rather than preconceived solutions. The ongoing evolution of the aircraft, culminating in the Block 20 upgrade, reflects years of operational experience translated into tangible capability improvements.

As the program continues to evolve, potentially incorporating unmanned systems integration and other advanced capabilities, it will likely remain at the forefront of fighter pilot training. The lessons learned at IFTS aren’t just relevant to Italy or even NATO; they represent broader truths about how pilots must be prepared for an increasingly complex and technology-dependent battlespace. The future of air combat belongs to pilots who can manage information, make rapid tactical decisions, and operate as part of distributed, sensor-connected teams. The M-346 program is ensuring the next generation is ready for that future.

I have recently visited the Italian International Flight Training School on Sardinia.

This is the third of several articles based on my interviews and discussions while visiting the Sardinia base in October 2025.

The AI generated image highlights the international engagement at IFTS, and the integration of the LVC ecosystem with the M-346 live aircraft. The level of integration is quite remarkable.