Managing the Panda and the Dragon: Challenges for Australian Strategy

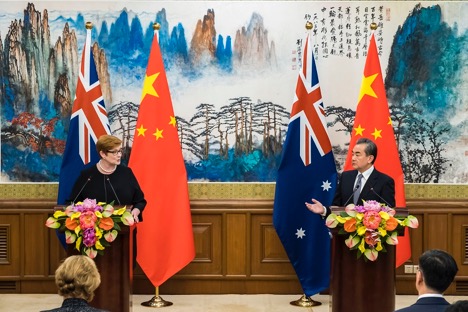

Foreign Minister Marise Payne’s announcement of a $44 million ‘National Foundation for Australia–China Relations’ to harness efforts of the private sector, cultural organisations, NGOs, state and federal agencies, and the Chinese-Australian community ‘to turbo-charge our national effort in engaging China’ is a good idea.

While there are mutually beneficial parts of the Australia–China relationship, we can’t hide from the fact that there are also increasingly stark differences—mainly on security and strategic issues.

That’s unsurprising, given that President Xi Jinping is an authoritarian leader of a one-party state who enjoys near-absolute power.

As a result, Australian government policy—and communication with the Australian public about the Australia–China relationship—needs to be able to manage both the panda and the dragon.

Experience shows that, for the new foundation to work, its board will need to include voices who can speak about all aspects of the relationship.

To ignore the security and strategic elements would make it like the Gillard government’s 2012 Australia in the Asian century white paper, which ignored obvious security risks and spoke glowingly about economic opportunities.

That initiative died because it simply didn’t describe the world we live in, in which security and economics and cultural issues are all intertwined.

So the board of this new foundation will need to have at least one defence and national security voice on it—which we’ll hopefully see when the government decides on its appointees.

The time of the Chinese state ‘hiding and biding’ under Deng Xiaoping is over. Now the dragon of the Chinese state under Xi is using its national power assertively and aggressively.

That’s true about its military power; a prime example is the South China Sea, where the Chinese military is aggressively seeking control of areas and features that it doesn’t own and which others claim.

It’s also true about its economic power. The extensive soft loans made under the auspices of Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative are already succumbing to corruption problems and leaving unsustainable debts. Beijing has also shown a willingness to use economic measures as punishment—for example, in its ongoing refusal to take Australian coal imports.

And in cyber power, the large-scale intellectual property theft and cyber intrusion into other nations’ systems for state and corporate purposes continues unabated.

Add foreign interference—including covert interference in the political systems of other countries—and technology like 5G communications (which Xi sees as a source of both strategic and economic power), and there’s a long list of Chinese actions that are causing problems in the relationship with Australia.

Unless the goals, policies, practices and actions of the Chinese state change, Australia, along with many other governments and nations, will need to balance mutually productive engagement with growing strategic differences.

It’s wrong to fall into the trap of talking about troubles with China simply as a bilateral issue for Australia to manage.

It’s even worse to talk about the problems in the relationship as stemming from the Australian government’s responses, when the root causes are the actions of the Chinese state.

The European Union has just ‘reset’ its own relationship with China. And that’s not to focus on harmony and speak more softly about differences. Instead, it is making ‘a further EU policy shift towards a more realistic, assertive, and multi-faceted approach’.

The EU needed to rebalance its relationship with China because, among other things, it now recognises the Chinese state as ‘an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance’.

So, it’s certainly worthwhile emphasising the harmonious, mutually beneficial elements of our relationship with China. But we know that more tough decisions will be required of future Australian governments because of the way the Chinese state is using its power in the world.

Examples include deciding what foreign investment to approve or knock back (we’ve already reached critical mass for Chinese investment in our nation’s vital infrastructure, as indicated by the rejection of a bid that would have given Chinese entities control of gas distribution along Australia’s east coast); stopping work in our universities that advances China’s military or state security capabilities—something that’s just not in our national interest; and responding to further punitive economic measures against Australian exports to China.

As the national foundation for Australia–China relations takes shape, it must develop in a way that mirrors reality and so take into account the connections between the security, economic and cultural issues that affect the relationship.

Not doing so will severely limit the foundation’s utility in helping to manage and communicate this important relationship to the Chinese and Australian people.

Michael Shoebridge is director of the defence and strategy program at ASPI.

Image courtesy of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

This article was first published by ASPI on March 30, 2019.