The Return of Direct Defense in Europe: The Putin Thread

I worked a great deal on Soviet-European relations in the 1970s and 1970s.

This included a significant amount of effort on the prospects for German unification which was the topic of a working group set up in the mid-1980s at the Institute of Defense Analysis.

I am currently working on a book with my co-author dealing with the return of direct defense in Europe and how to deal with the Russian challenge.

Clearly, in terms of the Russian challenge, the key thread in the post-2014 period is the life. politics and agenda of Vladimir Putin.

He comes to Europe in the mid-1980s and his views are forged in East Germany and the Soviet Union and lives through the turbulent years of collapse and recovery in Russia of the 1990s.

He believes strongly in the return of Russia to the world stage, and to a Russia which is an alternative to Western policies and values. He has also risen to power with the resurgence of Russian orthodoxy as well, which provides the national identity for many Russians who have seen the return of Russia.

For Putin, shaping a resurgent Russian agenda has been at the heart of his efforts. The military has provided tools for this effort, but have not driven this effort.

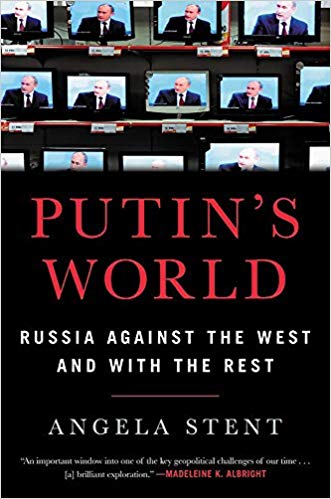

Angela Stent’s recent book Putin’s World provides a very comprehensive look at Putin’s approach to power and the largely flawed Western powers attempts to understand the Putin agenda for the return of Russia to the world stage. She provides a comprehensive look at the rise of Putin’s agenda and the largely irrelevant Western attempts to deflect or more accurately incorporate that agenda.

Not surprisingly she is very critical of President Trump and does underscore the conflicting agendas within his Administration. But the more compelling challenge does not lie with the United States or Donald Trump, it is about the evolution of Europe itself.

With a Germany clearly demonstrating little or no leadership with regard to direct defense, and wishing to preserve its options in dealing with Russia, the question becomes how will the evolution of Europe interact with and be shaped by and influence the evolution of Russia itself?

We are facing sooner rather than later the post-Putin world, and the Putin world has been one of Russia being governed by a regime rather than a state, as one analyst has noted.1

Her book largely ignores the core part of Europe which has provided a very strong political-military response to Putin, namely, the states building defense capability in the Polish to Nordic arc. It is a book about the major European powers, the UK, France and above all Germany.

It is not difficult to be critical of President Trump for his diplomatic appraoch but he has led an effort to rebuild the US military and has reinforced American capabilities to work with those states in Europe wishing to defend themselves.

She argues in her conclusion that we need a more realistic policy to deal with Russia.

In the absence of a broader agreement between Moscow and the West, Russia will continue to nurse its growing list of grievances against the US and Europe.

The West’s task for the rest of Putin’s tenure is to exercise strategic patience while containing Russia’s ability to disrupt transatlantic ties as it strengthens its defenses against Russian incursions. It must consistently and robustly push back against Russian interference in Western elections.

But it must also be prepared for new challenges as Putin focuses on building up Russia’s artificial intelligence capabilities and deploying its considerable cyber prowess.

Yet the US and Europe also should be prepared to reengage more actively with Russia should the Kremlin step back from its current confrontational policies and moderate its anti-Western stance.2

But from my point of view, rather than focusing on Trump, we need to ask ourselves how the American and leadership got it so wrong about Russia from George W. Bush, to Clinton, to Obama Administration’s?

The question of how to frame the key questions for shaping a realistic and effective way ahead to compete with the 21st century authoritarian powers is crucial.

It is not about the “end of history” and the engine of progress.

It is about how democracies can survive and thrive while the 21st century authoritarian powers expand their influence within their societies and compete globally, while we continue to deny ourselves the signifiant opportunity of targeting the internal publics within these authoritarian societies.

We will clearly be dealing with both post-Trump and post-Putin powers sooner rather than later, so how would we shape a more realistic agenda to deal with the 21st century authoritarian powers, of which Russia is not even the most powerful?

And not only did leaders in this period mentioned get Russia wrong, that is clearly even in second place to our mis-understanding about how to deal with the new China and its authoritarian global agenda.

And given that these two states are fueling a global rise of authoritarianism, we are not a period of normal diplomacy for sure.

What we are seeing is a major reworking of the Western agenda in terms of the constitutional crises in the United States, Europe and the UK. Clearly, Putin is playing off of these crises, but the continued economic weaknesses of Russia, with growing levels of dissent interacting with an increasingly diversified West, might actually pose a more significant challenge for Russian transition than a unified West.

There are clearly various political alternatives in the West as it diversifies which post-Putin leaders can identify with and work with.

And there is always the prospect that key Western states will directly work within Russia to undercut the authoritarian regime.

Political warfare is not just a one way street.

See also:

21st Century Authoritarian Powers and the Reshaping of Warfare in the Contest for Global Leadership