NATO Expansion: Rethinking the Limits of Direct Defense of Europe

Little noticed amid the controversies President Trump sparked at the recent NATO summit, the United States will support North Macedonia‘s membership in the NATO alliance. Although fewer than one in 100 Americans could find North Macedonia on a map, the United States will pledge its entire arsenal of ground, air, naval, and even nuclear capabilities to defend North Macedonia. In return, North Macedonia can’t provide much. It has only 12,000 troops in its armed forces, using old equipment and possessing little military capability.

It’s time to stop NATO expansion. A larger NATO embroils the United States in obscure regional disputes, commits it to defend exposed countries, and unnecessarily antagonizes the Russians. By incorporating weak states with short democratic histories, expansion also undermines public support for NATO, one of the world’s most successful military alliances.

NATO expansion began at the end of the Cold War, bringing the former Communist states of eastern Europe into the Western alliance. This made a lot of sense for countries like Poland, the former Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania. But the process kept going, incorporating countries progressively weaker and closer to Russia. NATO came to be regarded like the United Nations, where broad membership was desirable, and anyone could join after meeting some minimal requirements. That’s how the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania and Balkan countries like Montenegro, Albania, and Croatia were able to join.

Lost in the good feelings of expansion was the alliance’s purpose: military security. Extending NATO’s security guarantee to the Baltic countries, for example, later created a major new military challenge to prevent a Russian incursion. Meeting this challenge required greatly expanded deployments to Eastern Europe and billions of dollars of additional spending. Yet, expansion continues. At the 2018 Brussels Summit, the alliance invited the Republic of North Macedonia to begin talks to join NATO. On November 22 the U.S. Senate voted 91-2, with virtually no debate, to approve the accession.

North Macedonia is not a bad country. It has transformed itself from a communist economy and polity and has contributed troops to NATO. However, incorporating it into NATO creates several problems.

First, eastern expansion angers Russia. When the Cold War ended, Russia believed it was promised that NATO would not expand eastward. Whether the United States made such a promise is still hotly debated. What is clear is that Russia believes NATO made the promise. Now Russia sees a hostile NATO increasingly squeezing its periphery. It notes that, except for Belarus, NATO with its client state Ukraine is today at the Wehrmacht front line of 1942. That NATO might someday launch an attack on Russia seems ludicrous to us. NATO has a hard time agreeing on anything. If the United States said the weather was partly sunny, the French would say it was partly cloudy just to show they were an independent force. Russia, however, looks at military capability, not intentions, and sees an existential threat.

Expansion also inflames anti-NATO sentiment by feeding skepticism about its benefits. One of the strongest arguments for the alliance is that it is better to have lots of rich, powerful allies when facing threats. Adding weak nations undermines this argument. Thus, President Trump has regularly criticized NATO as a “bad deal” for the United States while French President Emmanuel Macron has called NATO “brain-dead.”

Finally, expansion incorporates countries with short and shallow democratic traditions. North Macedonia, like the newly added NATO countries of Croatia, Montenegro, and Albania, has made great strides in improving governance, for which they all deserve credit, but they lack the robust institutions that justify military burdens to NATO publics.

Someday this over-expansion will produce a crisis. Perhaps the crisis will arise from an intra-NATO dispute; perhaps from a local dispute that involves, for example, long-standing tensions between Serbia and its NATO neighbors Croatia or North Macedonia; or perhaps the treatment of an ethnic minority like Russians in the Baltic countries.

If dragged into messy conflicts in which they have few interests, countries may come to openly question the entire NATO project and endanger a key element of European, indeed, global stability.

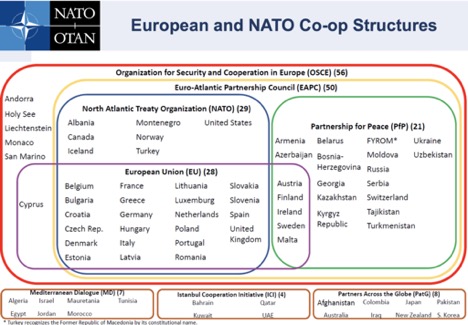

NATO needs to draw the line now. Behind North Macedonia are nearly 20 other partners who might also want to join NATO. And who can blame them. By joining NATO they gain security and status at little cost. Stopping expansion does not mean abandoning the many partner countries working with NATO. They can remain as partners, participating in military training and diplomatic coordination, but without the security commitment that is so costly to the United States and irritating to Russia.

Mark Cancian, a member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors and former senior OMB official, is a defense expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

This article was published by Breaking Defense on December 13, 2019.