The Strike Enterprise and the Royal Air Force

With the signing of AUKUS, Australia certainly closely aligned its way ahead with regard to weapons development and acquisition with the United States and the Britain. While most attention has been paid appropriately to TLAMs and long-range strike, what is Britain doing in the strike area of note for Australia?

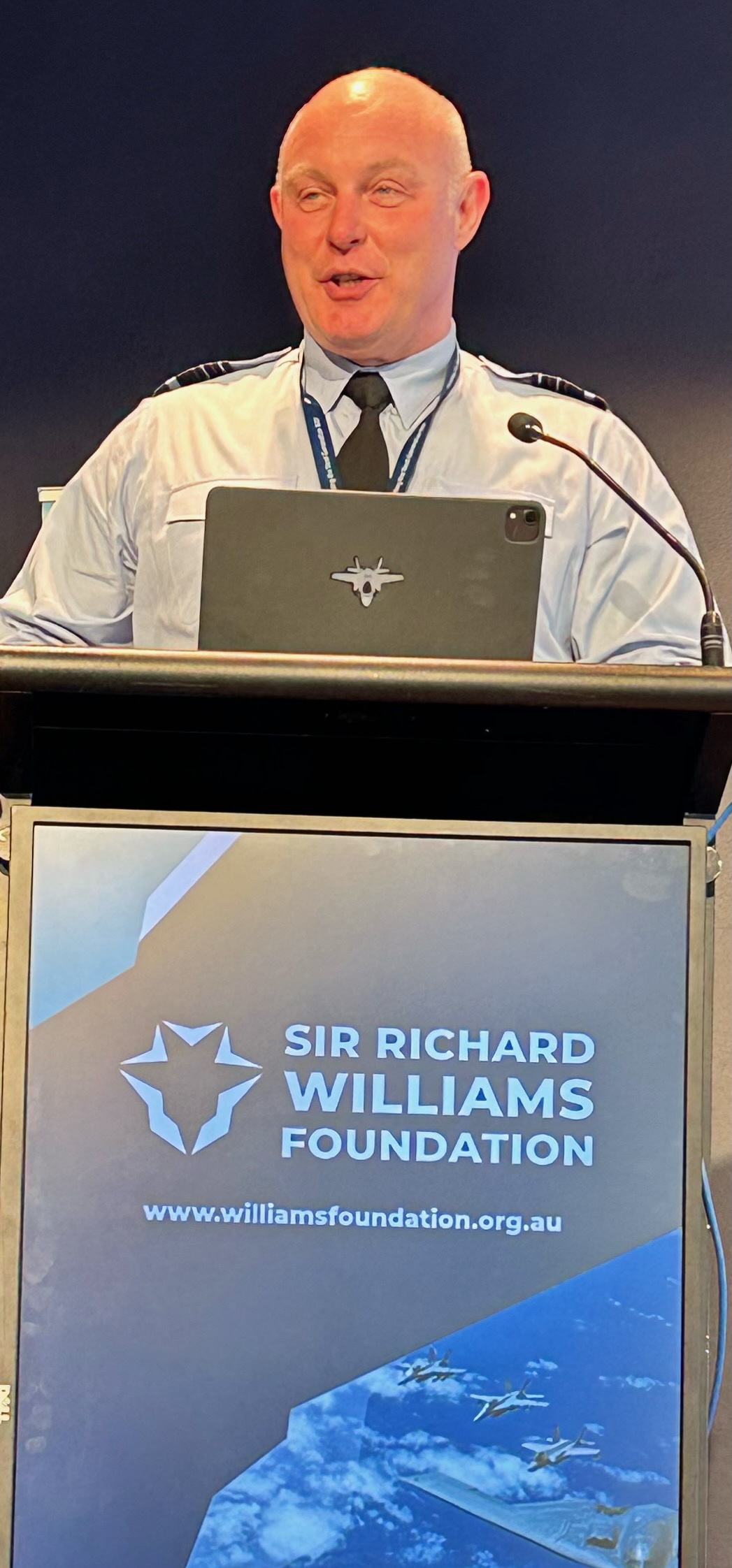

At least part of an answer to that question was provided by the presentation by the current head of the RAF, Air Marshal Harvey Smyth, to the seminar. In his presentation, he focused on the RAF’s experience with the evolution of its strike enterprise in terms of the development of its airborne strike force as well as providing a very helpful reflection on what the experience of the current conflict in Ukraine and Russia might mean for working a way ahead in the strike area.

Smyth started his presentation this time as he did the last by citing the importance of the UK’s “refresh” of the strategic defence review which was issued in March 2023 at almost the same time as Australia’s DSR. The “refresh” reaffirmed the core approach of the earlier strategic review but emphasized that the pace of change was accelerating.

And obviously there was a major war ongoing in Europe, which although referred to often as the conflict in Ukraine, I would label it more accurately as a NATO-Russian war in Ukraine. And given the central impact of this war on British interests, it obviously is having a major impact on British thinking as well.

Indeed, Air Marshal Smyth noted that 80% of his “day job” was focused on Ukraine. The “refresh” underscored that “We are now in a period of heightened risk and volatility that is likely to last beyond the 2030s.

IR2023 updates the UK’s priorities and core tasks to reflect the resulting changes in the global context.

“First, IR2023 responds to Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine. Putin’s act of aggression has precipitated the largest military conflict, refugee and energy crisis in Europe since the end of the Second World War. It has brought large-scale, high intensity land warfare back to our home region, with implications for the UK and NATO’s approach to deterrence and defence.

“As IR2021 set out, Russia is the most acute threat to the UK’s security. What has changed is that our collective security now is intrinsically linked to the outcome of the conflict in Ukraine. We must also analyse, learn from and adapt to the changing nature of warfare – notably in the land domain.”

So what is Britain learning?

According to Smyth, the war is proving amongst other things that “possessing the ability to successfully execute deep strike missions in a sustained manner, with precision and pace amongst a very dense and complex defense system, whilst in parallel defending against the enemy’s ability to conduct similar operations against you is a fundamental cornerstone to modern high intensity conflict.

“Hence, President Zelensky has continued to campaign around the need to gift additional long-range capability like the Storm Shadow cruise missile.

“This missile is currently being utilized with very positive effect. And we’ve recently witnessed and many successful Ukrainian strikes against targets like the Russian Black Sea Fleet, deep in Crimea hugely symbolic in terms of Ukraine’s ability to reach deep into Russian held territory, specifically in terms of penetrating one of the world’s most densely complex defenses to achieve precision effect against strategically important targets.

“This is fundamentally altering their dynamics of this whole conflict.”

Smyth’s example is an important one.

What exactly is the relationship among an ability to deliver long range strike and war termination, deterrence or “victory”?

The NATO-Russian war in Ukraine is raising a lot of questions concerning the relationship of strike to what kind of warfighting and diplomatic outcomes occur and are desired. And the question of what kind of strikes lead to WMD escalation remains a critical one as well in this war.

It is not an exercise: it is not a drill: it is a war in the center of Europe and is driving significant change in the thinking of a number of European countries bordering Russia with regard to what their strike posture needs to be facing Russia.

A key element of the evolution of strike involved in Ukraine clearly is with regard to land-based operations utilizing drones and a decentralized (to put it mildly) C2 system. Here Ukrainians have used a variety of drones to strike and kill Russian ground forces by a combination of space-based commercial capabilities, cell phones, and localized decision with regard to targets.

The Russians have used their drones to attack infrastructure and inflict civilian causalities. This is a good reminder that authoritarian states and liberal democracies have very different targeting philosophies and any asymmetry in this regard musts be considered in warfighting and deterrent calculations.

This dynamic of strike and defense is a key one and Air Marshal Smyth warns: “We should pay particular attention to Russia’s ability to sustain an extremely capable long range attack force, bringing to bear on a routine basis coordinated standoff attacks with cruise missiles, hypersonic weapons, and one way attack drones targeting Ukraine’s critical national infrastructure on a very regular basis.

“This is a point that will become ever more important as we enter another winter of warfare, where the targeting of energy and power supplies adds a dramatic humanitarian effect and dimension to the challenge.

“For me, the biggest lesson here is that any discussion about the development of multi-domain strike capability must go hand in glove with the discussion around your own integrated air and missile defense. One must be able to defend against the adversary’s ability to strike you once you break through their defenses to strike them.”

The remaining discussion by Smyth focused on RAF considerations concerning the evolution of the strike enterprise. Here he focused on the evolution of the Storm Shadow to a new family of strike weapons, which they have labelled Selective Precision Effects At Range (SPEAR).

This family of weapons is being developed by the European company MBDA where especially important is the UK-French weapons cooperation. But these weapons are being developed by a construct created earlier in the UK called the Complex Weapons Project which was set up by Lord Drayson, then the Defence Minister, to build weapons in an era of defence dollar scarcity.

I remember this development well for I was working at the time for the U.S. Defence Acquisition Chief, and then Secretary of the Air Force Mike Wynne. In a 14 July 2008 article by Craig Hoyle, the nature of the enterprise was identified: “Including MBDA, Qinetiq, Roxel, Thales Missile Electronics, Thales UK and the MoD, the partnership was formally launched with a signing ceremony at the show involving Minister for Defence Equipment and Support Baroness Taylor. “Team CW will help to maintain the UK’s key skills and technologies in missile development and protect our operational sovereignty in this sector for the future,” she says.

“This is a real landmark,” says Team CW industrial chairman and MBDA UK managing director Steve Wadey. “It has taken radical change in industry and the MoD to reach this point.”

“The new framework seeks to remove duplication, simplify platform integration, encourage modularity and provide planning stability to the UK’s guided weapons sector. This has suffered a 25% decline in its business over the last few years, but is expected have a potential worth of £6 billion over the next decade, says Wadey.”

With this approach and with a strong partnership with the French MoD, the RAF has benefited from the arrival of Storm Shadow and building the new SPEAR family. But as Smyth notes the time line envisaged for SPEAR pre-dates the new situation, and how do we accelerate building the new generation of weapons?

Air Marshal Smyth also underscored that it was important to work the relationship between high-end precision weapons with less costly and more numerous weapon stocks in equipping the force. What is the right balance? How to fund it? How to deploy it? How to connect strategic and tactical effects from the use of such an integrated weapons enterprise?

He noted: “High tech weapons are of course clearly used (in the war in Ukraine), but all must be defended against and these one way attack drones offer a very significant cost differential compared to defensive systems, sending a cardboard drone to an airfield that’s being defended by an S-400s.

“This can potentially induce a critical stockpile imbalance and this means that saturation weapons can draw fires from the defender to create an undefended gap because of stockpile depletion, which risks ultimately a loss of control of the air.

“Based on such experiences from Ukraine, we’re looking very closely in UK at our future weapons mix. We are trying to understand this in a number of ways. Again, unfortunately, the details of which becomes very classified very quickly.”

But he did underscore two key areas where he saw the need for missile modernization which needed to be made for the RAF going forward.

The first involved providing “a proper long-range strike capability for the F-35.” This will be done with the coming of the SPEAR family of weapons.

The second involved “the RAF current lack of a viable standoff anti-ship weapon. This was a very hot topic for our last defence secretary. And at present, we’re investigating a range of options to meet this requirement and are working with France on two different missile concepts under a specific program.”

Air Marshal Smyth concluded: “An appropriate mix must constitute weapons that contribute to deterrence because of their capability and or their mass, alongside weapons that can be manufactured at a pace to sustain follow on stockpiles, and continue to feed the fight. Getting this balance right is critical, and will undoubtedly be informed by the specific adversity we face.”

Featured Photo: Storm Shadow – Take off Warton (November 2015) Credit: Eurofighter