Characterizing the Putin Narrative: The Code of Putinism

As I have argued earlier, Putin has shaped a narrative over time about Russia, its state and its society and its role in the world. This narrative has been shaped by words and actions by the President over time and expresses his version of 21stcentury authoritarianism and how a “great authoritarian power” can shape its role in the world.

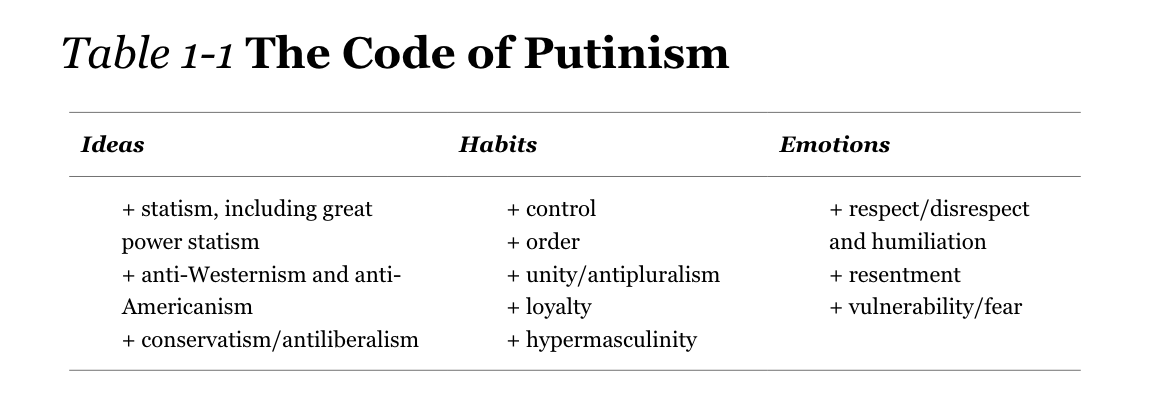

Brian Taylor in his book The Code of Putinism provides an interesting characterization of the Putin narrative writing process in terms of what he labels the code of Putinism. The table below captures his argument of what he sees as the essential elements of Putinism.

What Putin has built is an approach which emphasizes the defense of conservative values, Russian orthodoxy, a strong central regime in “vertical” control of the country, and over time playing off of Western developments in the post-Cold War period as providing a threat to Russia and its interests, requiring a Russian “reset” but not the one that Mrs. Clinton had in mind when she articulated this objective during her time as Secretary of State in the Obama Administration.

What Putin has built is an approach which emphasizes the defense of conservative values, Russian orthodoxy, a strong central regime in “vertical” control of the country, and over time playing off of Western developments in the post-Cold War period as providing a threat to Russia and its interests, requiring a Russian “reset” but not the one that Mrs. Clinton had in mind when she articulated this objective during her time as Secretary of State in the Obama Administration.

There was reset for sure, but it was about the Putin regime challenging what many Western analysts call the “rules-based” order in favor of one looking more like a return to great power politics of the 20th or 19th centuries.

Although in the Putin narrative, the United States is painted as the adversary who has driven Russian to protect its interests by armed intervention in Europe and in the Middle East, actually the biggest challenge to Putinism comes from Europe and the “near abroad” countries wanting to be part of a broader European effort for modernization, than joining a new Russian club of autocrats.

Although, the evolution in parts of Central Europe towards 1930s types of authoritarianism might provide the opportunity for a Russian club to emerge, notably as China and Russia are sponsoring a viable 21st century authoritarian effort.

Putin has positioned Russia to “punch above its weight” in global affairs.

“The code of Putinism has at its core the notion that Russia must be a strong state and a great power, and it is highly suspicious of the United States and the global system it promotes and upholds. Feelings of humiliation and resentment in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse further fuel this drive to restore Russian power.

“Putin’s Russia is not seeking global hegemony, but it does want to upend the Western-dominated order that promotes democracy and human rights and insists on the right of Russia’s neighbors to choose their own foreign policy course independent from Russian tutelage. It wants to be treated as an equal great power deciding the key issues in global security, respected and deferred to by the other great powers, especially the United States. Putin wants, to borrow a phrase, to make Russia great again.”1

Russia under Putin sees its agenda of restoration of its proper place in the world comes into direct conflict with the Western world’s view of itself.

The problem is that the West sees the current international order as broadly legitimate and interprets Russian assertions of its perceived interests as a challenge to peace and stability. Russia wants great power diplomacy as practiced in Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, something the West sees as no longer viable in the twenty-first century.

Putin has been quite clear about how he would like the Western approach to change. He favors a consortium of great powers working together to shape the way ahead for the global order, which, of course, means tearing up a considerable part of the liberal democratic approach to global order.

Russia as a respected great power, one of a new Big Three (the US, China and Russia), consulted on all major international questions, and deferred to on issues within its sphere of influence—this is the goal of a Putinist foreign policy. This is what “winning” would look like for the code of Putinism, the purpose of strenuous efforts to punch above Russia’s weight.2

Taylor underscores that many global actors reject such an approach out of hand.

“Many states in the international system aren’t prepared to return to a Concert of Nations concept. Most importantly for Russia, this vision is no longer viable for Europe…. Not only do the major western European powers resist a return to a spheres-of-influence world but so also do the smaller states whose fates would be decided by the great powers.

“Experts have observed that the countries in the former Soviet space in which Russia has used military power without a host government invitation since the end of the Cold War—Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine—are also among the most resistant to Russia’s effort to keep them in its orbit. As one former US diplomat put it, “the harder Russia squeezes its neighbors, the more they will turn to Euroatlantic institutions as a refuge.”3

The challenge for the West though is that Russian interests cannot be ignored with regard to the evolving European order, nor can Russian reshaping of political geography accepted either.

“The concession Putin wants—recognition of a sphere of influence in the former Soviet space—is one the West almost certainly will refuse to give. More dialogue is certainly called for, but after the Ukraine crisis, both sides are more suspicious than ever.

“And, it is worth emphasizing, NATO expansion arguably is not even the most vexing issue for Putin and his group—colored revolutions in neighboring states increased feelings of vulnerability and encirclement in the Kremlin at least as much as NATO enlargement did. The challenge of a new European security architecture ultimately is more political than military.”4

Looking beyond Putinism, the question is how will Russia evolve and deal with the fundamental challenges which have been the downside of the restoration of Russian order shaped by the Putin narrative?

Taylor cites one Russian analyst’s characterization of the “five circles of hell” which Putinism has created and which his successors will need to deal with.

These five circles are: 1. An inefficient economic system built on crony capitalism capitalism and state business; 2. A central political system in which all key institutions outside the presidency—political parties, the parliament, civil society—have been “destroyed”; 3. A federal political order in which the regional elite has been “castrated” in favor of weak and talentless leaders installed from the center; 4. A foreign policy in crisis, marked by confrontation with the West and partnership with a China that will want some returns from its investment in the relationship; 5. A weak state, in which the government and bureaucracy are incapable of regularized governance and decision-making because of habituation to “manual rule.”5

Taylor argues that the question of the evolution of Russia after Putin will intersect and interact with the major changes going on in the West as well. Putin has put down his marker on stopping NATO and EU expansion; but the question of how the West evolves, in terms of the next phase of EU development, how the major states in the West will deal with economic, political, diplomatic and military challenges, will shape the way ahead for Russia as well. But the reverse is also true.

The 21st century authoritarian powers are directly impacting on Western development, and the least significant aspect of doing so is cyber intrusion in elections. The broader engagement within the economies and interest group structures in the West is far more significant.

The code of Putinism, in contrast, embraces conservative and illiberal values of tradition, hierarchy, and order. On Russia Day in 2017, Putin emphasized the “significance of our own roots and traditions,” the need to maintain a “strong, self-sufficient, independent country,” and the centrality of “the power of the state in securing political stability, unity of purpose, and the consolidation of society.”29 Putin, skeptical of ever reaching accommodation with the West, increasingly has sought to undermine the image of the West and its liberal values, both at home and abroad, andhe seems to have notched some major successes in this effort.6

Footnotes

- Taylor, Brian D.. The Code of Putinism (pp. 166-167). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

- Taylor, Brian D.. The Code of Putinism (p. 191). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

- lTaylor, Brian D.. The Code of Putinism (p. 191). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

- Taylor, Brian D.. The Code of Putinism (p. 192). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

- Taylor, Brian D.. The Code of Putinism (p. 207). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

- Taylor, Brian D.. The Code of Putinism (pp. 208-209). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.