Australia Builds Its New Class of Offshore Patrol Vessels

Two broad findings can be drawn from my five years of visiting Australia and working with the Australian Defence Force.

The first is that they are very focused on building out as integrated a force as they are capable of doing, and that means not only leveraging an advanced asset like the F-35 but shaping common combat systems throughout the force. This is why they refer to their effort as building a fifth-generation force; it is not just about interoperability but about building out an integrated force across the spectrum of crisis management and warfare.

The second is that they are keen to enhance their ability to build a more sustainable force, which in shipbuilding terms means to put in place what they refer to as “continuous shipbuilding.”

What this means is working ways to have an ongoing ship build, modernization and sustainment process.

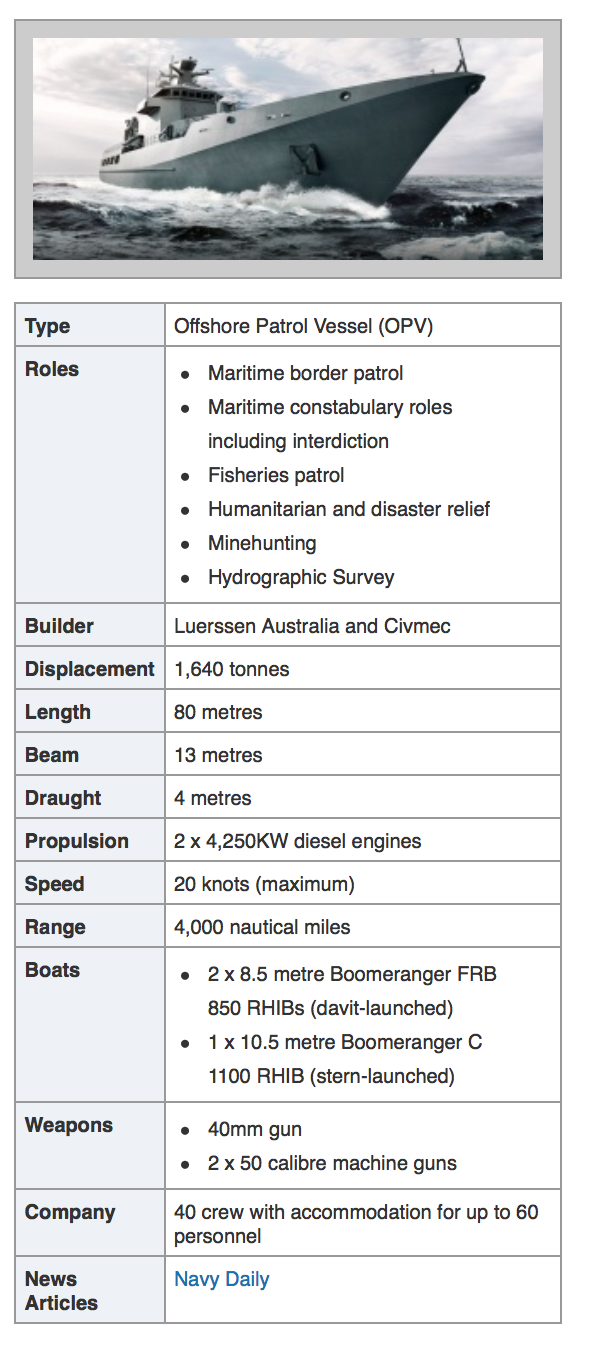

The new Offshore Patrol Vessel illustrates very well the new approach.

First, of all the OPV is part of an overall crisis management approach. During my last visit to Australia, I had time to meet with the head of the Maritime Border Command, Rear Admiral Lee Goddard. And as he talked me through the map of Northern Australian waters and the challenges facing his command, it was clear that the command’s capability had to be integrated with the overall ADF.

The new OPVs are to be operated both by his command and the Royal Australian Navy, and will share common combat systems, integratable with the RAAF and the RAN, and the OPV program itself is seen as a launch point for a key part of Australian shipbuilding, namely, the patrol vessel global market.

In 2017, the Australian Navy announced the selection of the design for an initial program of 12 OPVs to replace the 13 active Armidale class patrol boats. These ships will be owned and maintained by the Royal Australian Navy, although a certain number will be assigned to the Maritime Border Command. And additional ships could be procured to meet other capability needs, such as the MCM or mine counter-measure mission.

According to an article by Stephen W. Miller:

Lürssen’s design is based on its OPV80 which is also in service with the Brunei Navy.

The design is noteworthy for its spacious layout for additional equipment, with the stern ramp RHIB launch and recovery system, and large helicopter flight deck. The vessel will have a displacement of around 1700 tonnes and a length of 80 meters. Their speed is around 20 knots while they have greater range and endurance than the current Armidale Class Patrol Boats they are replacing.

The vessel will have a 40mm Bofors gun and modular mission packs including unmanned aerial systems. It has a crew of 40 but can accommodate up to 60. The vessels will utilize a modular mission payload system similar to that used by the Danish Navy and the United States Navy’s Littoral Combat Ships.

Mission equipment will be fit into 20-foot containers and placed onto the ship as needed for assigned tasks.

A MoD spokesperson suggested that “The new OPVs will operate alongside Australian Border Force vessels, other Australian Defence Force units and its regional partners.”

But at the heart of the program is its common combat systems and C2 systems which will allow the ship to be part of an integrated “kill web force” which will allow it to become a scalable presence asset by reaching back to Australian or allied connected combat assets.

As one analyst put it: “To compare the ACPBs to the OPVs is somewhat like comparing a Cessna to an F-35 in regards technology and system performance. In a nutshell, each OPVs will act as a coherent ‘Node” within a wider shared picture compilation and information dissemination environment.

“Not only will the OPV offer greatly improved sea-keeping and endurance over the ACPBs, but it will also be able to actively contribute with other ADF and Allied force elements within a Joint Force combat environment.

“In additional to nominal Boarder Protection Patrol functions (Patrol/Deterrence/VBSS etc.), the increased Electromagnetic environmental awareness and data connectivity intrinsic to the OPV will enable it to either act as a forward deployed sensor (with wider Common Data Link connectivity to both Tactical and Strategic assets), or as a mothership for its own ‘Constellation” of Unmanned Systems (UAVs/UUVs/USVs), or as an interactive communications relay node in Denied, Degraded, Intermittent, Low-bandwidth (DDIL) SATCOM environments.

“Succinctly, the new OPVs will be better able to actively contribute to and assure a wider Battle Group information environment that do the present tranche of Australian Navy Frigates and Destroyers.”

When at the last Williams Foundation Seminar held on April 11, 2019, I had a chance to discuss the OPV approach with the recently retired head of the Australian Navy, Vice Admiral (Retired) Tim Barrett.

Barrett highlighted how the OPV fitted into the larger shipbuilding picture and evolution of the integrated air-maritime force.

“It is clearly not just about the platform, or buying a replacement platform. With the contract, we are kick starting an entire industry in Australia. We will be training those who will build the launch platforms, but those individuals will be part of a continuous build process and will be part of the design, modernization and sustainment process. It is part of establishing a sovereign industrial capability.”

But it is not just that.

It is about putting in place a key approach to ensure commonality across the fleet with regard combat and C2 systems, and a commonality that reaches deep into allied fleets as well.

“We are building the ship around a mothership concept, which means that its ability to link and work with not just systems operating from the OPV but within the ADF more broadly is a critical one. With this platform as with our other new ships, we have separated the decisions on making the hulls from the decisions about the onboard systems. The latter is really the key part of ensuring we have an integrated not interoperable force.”

He drove home the point about viewing these assets as nodes within the kill web.

“We have to start treating these platforms as nodes, which can both leverage other ADF or allied capabilities, and contribute as well to the capabilities of a seamlessly stood up task force.”

The mother ship concept is at the heart of what a kill web OPV can do. It is anticipated that both UAVs and UUVs could be operated from the ship. That data will go to the ship but can be distributed into the operational space. And given that it is data, how that is managed, handled and distributed will be determined not just by technological capabilities, but also with regard to the evolution of processing technologies and decision making algorithms.

Put in other terms, the OPV can host capabilities, which are reaching deep into the future, but capability of delivering capabilities for today’s operating force.

It was very clear from my discussions with Rear Admiral Goddard, that given the geographical expanse, which the ADF and the Maritime Border Command has to deal with, only an integrated force can combine presence with scalability to get the kind of result Australia will need for its sovereign borders policy. And in his view the new OPVs will be an important contributor to his command and to the integrated force.

It can not be overemphasized the priority on the integrated aspect; the Aussies are clearly rejecting what is often seen in the United States as Balkanized logistical support and tower of Babylon C2 and combat systems approaches.

They seek to gain a strategic advantage from being a smaller more agile force operating in a dangerous and busy neighborhood.

This article was first published on May 12, 2019.

http://www.navy.gov.au/fleet/ships-boats-craft/future/opv

Public-AIC-Plan-SEA-1180-Phase-1-OPV-LuerssenSee also the following:

Vice Admiral (Retired) Tim Barrett: Shaping a Way Ahead for the Royal Australian Navy