Australian Strategy at a Turning Point: Implications for the United States

As Australia engages in shaping its role in the changing global dynamics of the 2020’s, a key challenge is to determine how best to protect its sovereignty with the rise of the 21st century authoritarianism and how to deal with the end, at least in its current form, of the American generated and sustained order or what the Aussies call the “rules-based order.”

The 21st century authoritarian powers are clearly focused on changing the rules of the game let alone the rules-based order. Although the United States clearly is a key ally of Australia and the dominant liberal democratic military power, that relationship clearly is not enough to sort through how best to protect Australian sovereignty.

The United States faced a key challenge in the early 1990s with the end of the Cold War. The United States could have chosen to strengthen its role as a global military power with the means most relevant to reinforce key allies, which would mean in military terms building an innovative, modernized and recapitalized naval and air force.

Or it could do what it did, which was to operate at range and engagement levels in dealing with far-reaching countries with forces threatening to the United States, but only by using terrorism as power projection means.

The United States went full bore down this path, expending significant human, material and financial resources in the Middle Eastern land wars. The United States built a large COIN oriented ground force with the navy and air force, not modernized for its global power projection role, but transformed into supporting elements of the ground forces.

In the words of one Marine Corps General, significantly involved in the COIN epoch characterized how he saw the shift after the collapse of the Soviet Union: “The U.S. national military strategy continued to shift as our nation adjusted to become the world’s sole superpower, with a perceived responsibility for policing the world. Many small states and nonstate actors filled the void left by the loss of the checks and balances of a once bipolar world They grasped the opportunity to forward their agendas, often at the expense of other. This new world order presented ample work for the men and women in uniform.”1

The General has put bluntly what clearly was the operative strategy of the Administration’s following General George H. Bush. This perspective was informed by the dominant belief in the liberal democracies, that globalization and the liberal democratic order went hand in hand.

And regional crises, provided an opportunity, to do humanitarian interventions, or stability operations which had the goal not of gaining geopolitical advantage but of planting the seeds for another player evolving and becoming a participant in the liberal democratic world.

The Iraq and Afghan engagements have transformed U.S. capabilities and policies. There is a clear exhaustion in the body politic with the “new world order,” and that certainly was one reason for the election of Donald Trump. What this should mean is that global engagement to simply enforce the “rules based order” needs to be replaced a sense of limits, husbanding of resources, and prioritization on dealing with the global authoritarian challenge. And in this regard, re-directing, replacing or recalibrating the worst effects of globalization.

Australia clearly faces a turning point as it confronts the new global situation created by the rise of the 21st century authoritarian powers, and the return of geopolitics as well as the need to radically rethink globalization.

Does Australia assume that the challenge is to protect the rules-based order and to contribute to global efforts, often but not exclusively led by the United States: Somehow China and Russia can become normal allies and by largely peaceful means can work a coda to the inherited “rules based order.”

Or is it about geopolitical contest and conflict with the 21st century authoritarian powers at the heart of the challenge?

In dealing with the second, Australia would need to expand the working relationship with core allies beyond the United States and to work with the United States as well with regard to how the rebuild of Australian infrastructure and the expanded use of Australian geography is in their joint extended deterrence interests.

The later may be on the way as the Aussies have just concluded their first bilateral air combat exercise and through their shipbuilding programs expanding their working relationships with Britain and France in the defense domain.

What this means for the United States is a return to the core question seen in 1991: Is the United States pursuing its global engagement driven by a liberal democratic ideology or is it going to focus on protecting its core national interests and rebuild its military to support those interests and to shape a strategic apparatus capable of using such instruments?

The first really has no inevitable limits, because we live in a “global village.”

The second is about a ruthless relook at what those interests are and whose allies the United States considers to be core ones.

My position on this is clear and has been from 1991 on. In that year, I did work for senior DoD officials where I outlined how Air and Naval modernization coupled with a strategy of backing regional influentials would provide a key way for the U.S. to be a key global power, but not a superpower.

And when we wrote our book on rebuilding American military power in the Pacific, our core focus was on how the United States with the new capabilities which it already had I hand or was developing such as the only tiltrotar force in the world, and the building of the F-35 enterprise could in fact shape a regional reinforcement strategy.

I did not then nor now believe that the United States should try to build a high end warfighting force which can defeat the 21st century authoritarian powers, for this is neither feasible, realistic, nor necessary.

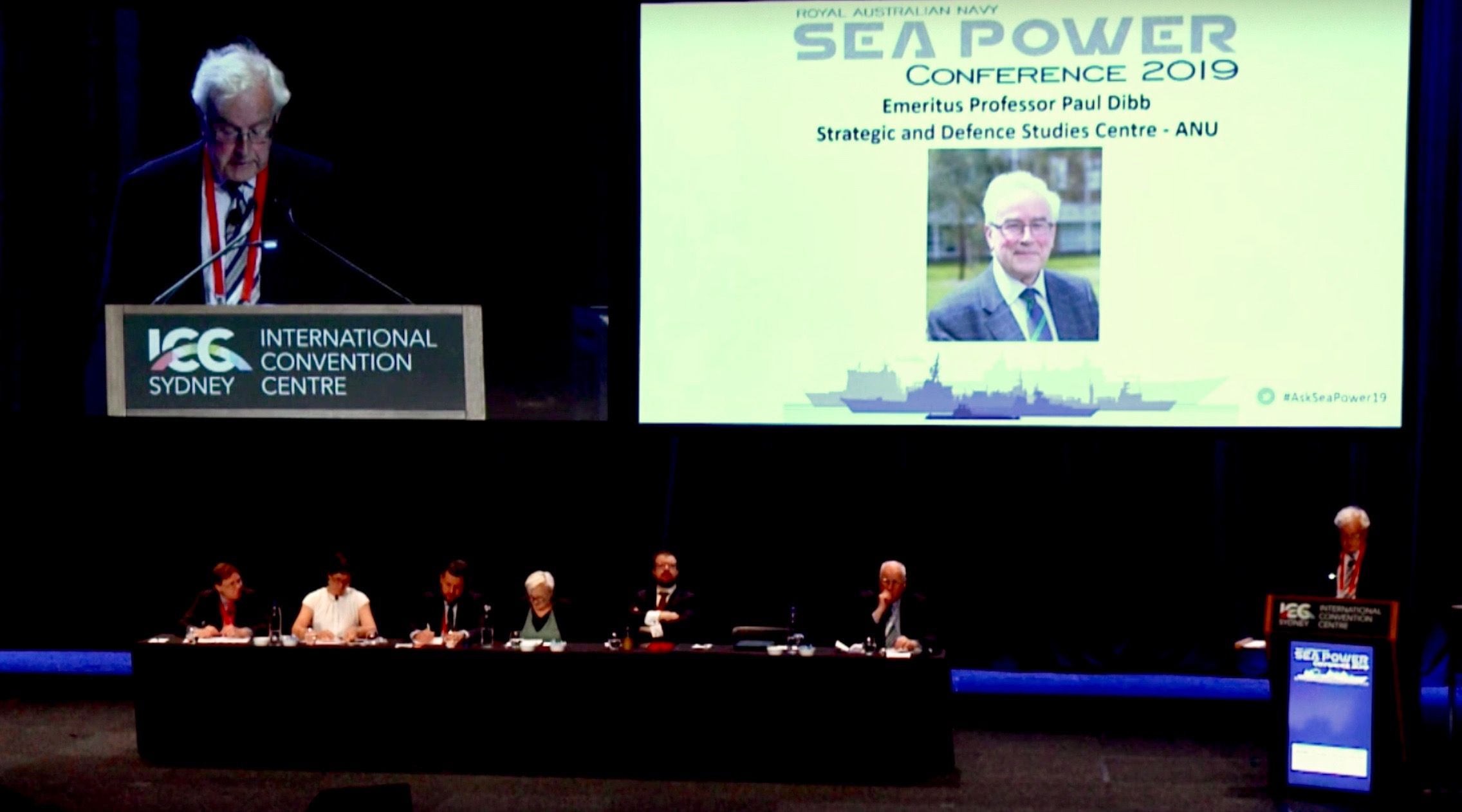

At the recent Royal Australian Navy Seapower Conference held in Sydney from the 8th through the 10th of October, Paul Dibb, the noted Australian strategist provided his perspective on Australia’s strategy at a turning point.

In it he clearly highlighted the importance of recognizing that the “rules-based order” was not the focus; rather it was dealing with the 21st century authoritarian powers which in his view are clearly working more closely together.

What follows is the well-thought out presentation by Dibb:

Australia’s international security outlook is starting to look very unpredictable and potentially threatening. Our defence planners must now deal with a world which is very different from any they have known before. America is undermining the international rules-based order and, at the same time, China and Russia are becoming increasingly assertive militarily and aligned in their anti-Western attitudes. All this is taking place as a crisis of democracy in the West is distracting it from wielding its national power more effectively.

We are now in a period of unpredictable strategic transition in which the comfortable assumptions of the past are over. We need to encourage imaginative strategic thinking about Australia’s future in a more dangerous world.

In this speech, I shall talk about two defence strategic planning challenges. First, I will address why we are now in defence warning time and the implications of this for mobilisation and the ADF’s expansion base. Second, I’ll explore with you my current research which analyses the new geopolitical alignment between China and Russia and what that means for the security of the West, including Australia.

Warning time and the ADF’s expansion base2

Australia’s strategic outlook is deteriorating and, for the first time since World War II, we face an increased prospect of threat from high-level military capabilities being introduced into our region.

This means that a major change in Australia’s approach is needed to the management of strategic risk. Strategic risk is a grey area in which governments need to make critical assessments of capability, motive and intent. Since the 1976 Defence White Paper, judgements in this area have relied heavily on the conclusion that the capabilities required for a serious assault on Australia simply did not exist in our region.

In contrast, in the years ahead, the level of capability able to be brought to bear against Australia will increase, so judgements relating to warning time will need to rely less on evidence of capability and more on assessments of motive and intent. Such areas for judgement are inherently ambiguous and uncertain.

The potential warning time is now shorter, because regional capability levels are higher and will increase yet further. This observation applies both to shorter term contingencies and, increasingly, to more serious contingencies credible in the foreseeable future.

How should Australia respond?

Contingencies that are credible in the shorter term could now be characterised by higher levels of intensity and technological sophistication. This means that readiness and sustainability need to be increased: we need higher training levels, a demonstrable and sustainable surge capacity, increased stocks of munitions, more maintenance spares, a robust fuel supply system, and modernised and protected operational bases in the north of Australia.

For the longer term, the key issue is whether there is a sound basis for the timely expansion of the ADF. Matters that would benefit from specific examination include: the development of an Australian equivalent of an anti-access and area denial capability (especially for our vulnerable northern and western approaches), an improved capacity for antisubmarine warfare, and seriously revisiting our capacity for sustained strike operations.

The prospect of shortened warning times now needs to be a major factor in our defence planning. Much more thought needs to be given to planning for the expansion of the ADF and its capacity to engage in high intensity conflict in our own defence in a way that we haven’t previously had to consider. Planning for the defence of Australia needs to take these new realities into account, including by re-examining the ADF preparedness levels and the lead times for key elements of the expansion base.

We must now refocus on our own region of primary strategic interest, which includes the eastern Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia including the South China Sea, and the South Pacific. The conduct of operations further afield, including in the Middle East and Afghanistan, and Defence’s involvement in counterterrorism, must not be allowed to distract either from the effort that needs to go into this planning or from the funding that enhanced capabilities will require.

This will demand a major change in Australia’s approach to the management of strategic risk. To the extent that capability for offensive operations against Australia were developed by a foreign power, Australia would have to rely on the more judgemental indicators relating to motive and intent than on evidence of capability. This would be compounded by the likely absence of an obvious warning threshold. To help manage this ambiguity and uncertainty, it would be vital for Australia to continue to have high levels of intelligence collection and analysis.

It needs to be acknowledged that recent strategic developments in our region also reflect a steady reduction in Australia’s strategic space. This is shortening the time that Australia has to understand, prepare, and – if necessary – to respond to adverse military developments.

The transformation of major power relations in the Asia-Pacific region is having a profound effect on our strategic circumstances. Without increases in our defence preparedness the options available to the government for the ADF’s involvement in contingencies that would be characterised by higher levels of intensity and technological sophistication, would run the risk of being severely constrained.

The issue for the longer term is whether we have built a sound basis from which to expand the ADF, especially our strike, air combat and maritime capabilities. Having such an expanded force would significantly increase the military planning challenges faced by any potential adversary and increase the size and military capabilities of the force it would have to be prepared to commit to attack us directly, or to coerce, intimidate or otherwise employ military power against us.

Attacks on Australia of an intensity and duration sufficient to be a serious threat to our national way of life would be possible only by an adversary’s forces with access to bases and facilities in our immediate neighbourhood. This needs to be taken into account when considering the development of Australia’s strike forces so that they have sufficient weight to deny any future adversary such military bases. This involves reconsidering the range, endurance and weapon load of our strike forces and the numbers needed for repeated strike operations in the archipelago to our north.

Any serious review of Australia’s evolving strategic circumstances will come to the conclusion that warning time is becoming shorter and that the management of strategic risk is becoming significantly more demanding. Thus, it is imperative that planning for the defence of Australia, and for operations in our region of primary strategic concern, resumes the highest priority. Re-establishing our foreign policy and defence presence in this part of the world should be our key priority.

We need to get rid of the 2016 Defence White Paper’s ill-advised proposition that the defence of Australia, a secure nearer region, and our global defence commitments should be “three equally-weighted defence objectives to guide the development of the future force”.

Finally, it needs to be recognised that the policy line that I am recommending is a continuation of Australia’s long-standing defence policy that we do not identify any particular country as a threat. Rather, we are responding to the significant improvement in high-tech military capabilities across the board in our region. We would simply be adopting an area denial force posture, like that of some other countries in our region.

The Geopolitics of China’s Alignment with Russia

We are in an era when the risks of major power conflict are growing. The most likely contenders are seen to be China, the rising power, and the US as the formerly dominant power now in decline. The other worrying contingency is conflict between Russia and NATO led by the US. But what about the third possibility: the prospect of China and Russia collaborating to challenge American military power?

Zbigniew Brzezinski warned that the most dangerous scenario for America would be a grand coalition of China and Russia united not by ideology, but by complimentary grievances.3

China and Russia are the two leading revisionist powers leagued together in their disdain for the West. Both these authoritarian states see a West that they believe is preoccupied with debilitating political challenges at home. Putin has disdain for what he sees as a Europe that is weak, divided, and bereft of morality. Xi Jinping believes that China is well on its way to becoming the dominant Asian power, possessing an alternative and successful model of political and economic development to that of the West.

China and Russia have commonly perceived threats and are now sharing an increasingly close relationship, including militarily. If the China-Russia military partnership continues its present upward trend, it will inevitably affect the international security order, including by challenging the system of US centred alliances in the Asia-Pacific and Europe.

This is not to argue that we are going to see a formal Russo-Chinese alliance but what we are observing is an ever-closer friendship of mutual alignment. Russia and China are economically complimentary; they are both secure continental nuclear powers; and they are both the dominant military powers in their own immediate regions. In their different ways, they probably see that the West’s current disarray favours them geopolitically.

So, what are the chances of Beijing and Moscow concluding that now is the time to challenge the West and take advantage of what they both consider to be Western weaknesses? China and Russia are well aware of the impressive military power of the US. But they both know that the US no longer enjoys uncontested or dominant military superiority everywhere.

Recognising this, it may be the time has come when Beijing and Moscow test America’s mettle and see if they can successfully challenge the US in both the European and Asian theatres at the same time. China and Russia may come to the decision they could successfully regain lost territories in such places as Taiwan and Ukraine. Beijing and Moscow perceive both these places as central to their rightful historical and cultural claims as great powers.

Russia and China are increasingly joining forces in the international arena to balance against America and their militaries are becoming much closer. Recently, their partnership has deepened to provide for increasingly advanced Russian military equipment sales to China, as well as joint military exercises in the Baltic and the East China Seas. On the 23rd of July this year, Chinese and Russian nuclear capable bombers rendezvoused in East Asia and carried out joint patrols.

Given Russia’s slow decline and China’s rapid rise, we might have expected that Russia would support Western efforts to balance China rather than undermine them. But the evidence now is accumulating to suggest that Russia’s relationship with China is deepening – especially militarily – and this carries distinctly negative geopolitical implications for the West.

The distinguished American historian, Walter Russell Mead, has described current Russian and Chinese military activities as “the latest manifestation of a deepening alliance between Russia and China.”4

So, what risks might Beijing and Moscow take to recover what both consider to be historical territories belonging to the motherland?

It is important to understand that in China and Russia we have two long-established cultures different from the Western tradition. They have deep memories of humiliation at the hands of the West. Both Russia and China have experienced historical circumstances when their societies have been weak and where the West has taken advantage of them. And they reject what they see as Western interference in their domestic political systems.

Both China and Russia have effectively used incremental territorial claims recently to their military advantage. China’s creeping militarisation of the South China Sea is now an established fact. Russia’s use of military force in Crimea and Ukraine has been imposed without effective military challenges from the West. In both Beijing and Moscow there is every reason why they should consider these as effective models to continue demonstrating their great power status.

It now looks as though China and Russia are combining their forces to balance against the US, which they see as the common enemy. The fact is that Russia’s relations with China are now much closer than ever before. China is strong and decisive enough to serve as a strategic partner while Russia seeks to reassert itself as an independent great power in Europe. For its part, China is responding to its newly competitive confrontation with President Trump’s America by deepening its strategic relationship with Russia. China has no other strong major power relationships either in Asia or Europe.

Both China and Russia are now allied in a quest to refashion the world order that is safe for their respective authoritarian systems. Both leaders have reasons to be gratified by global trends and they are “out-gaming” the West. Beijing and Moscow believe they cannot afford to have poor relations with the other at a time of great strategic opportunity and with the Western alliance now in disarray.

There can be little doubt that the build-up of their respective military forces suggests they are both increasingly prepared for conflict with the West.

The rapid development of China’s military capability, together with serious reforms in Russia’s military forces, is occurring at a time when America can only fight one major regional conflict and mount a holding operation in another regional conflict. Washington’s National Defence Strategy acknowledges that the central challenge to US security is the re-emergence of long-term strategic competition with China and Russia.5

The actual words used are that the fully mobilised US force will be capable of “defeating aggression by a major power” and “deterring opportunistic aggression elsewhere.”

America aims to maintain favourable regional balances of power in both the Indo-Pacific and Europe. But that will be a particularly challenging task, given China’s rising power in Asia and Russia’s flexing of its military muscles in Europe.

So what are the implications of all this for the West?

The fact is that the West is entering a period of great strategic disruption and instability. America’s obsession with looking inward and making America Great Again opens fresh geopolitical possibilities for China and Russia.

Implications for Australia not only relate to the dangers of armed conflict involving China and Russia against the West. Some of these conflicts might involve Australia more directly. Moreover, there is another important issue for Australia: and that is Russia’s continuing supply of advanced weapons to China and their growing presence in our region.

Which leads me to my final question: is there nothing that can be done about the growing strategic alignment between China and Russia?

The classical balance of power response to such a question would be to postulate an American attempt to detach Russia and cement its partnership with the US. In my view, however, nothing is likely to change the current adversarial nature of US-Russia relations.

Brzezinski’s warning that the most dangerous scenario facing US security would be a grand coalition of China and Russia is now becoming an established geopolitical fact.

Footnotes

- Brig. Gen Jason Q. Bohm, USMC, From the Cold War to Isil: One Marine’s Journey (USNI Press, 2019, p. 245

- For an earlier analysis of this topic, see Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith, Australia’s Management of Strategic Risk in the New Era, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, November 2017.

- Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives, New York: Basic Books, 2016, p. 35.

- Walter Russell Mead, “Why Russia and China Are Joining Forces,” The Wall Street Journal, 29 July 2019.

- National Defence Strategy of the United States of America, Washington DC, 2018, pp. 1-2.