A Conversation with Emerson Carr: A Profile in Courage

William Faulkner in his Nobel Prize in Literature Acceptance Speech in 1949 underscored what he saw is a goal towards which men might strive:

“I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail.

“He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.”

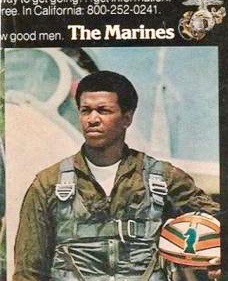

And certainly, no better words can capture the life of Emerson Carr, USNA ’69 , USMC Pilot, Senior Executive in American Industry and after all his greatest accomplishments, his true time of testing was yet to come.

Em and sadly the late Dr. Calvin Huey, who just passed away, were the first two African American Football players in Naval Academy History.

He was my classmate at the Naval Academy and we went to flight school together as well.

We both served at the time of the War in Vietnam.

The difference was that Em was offered an NFL future but chose to enter the Marine Corps and serve his country.

We had a chance to interview Emerson my classmate, fellow Marine Pilot and friend for fifty years to show all Americans why he truly earned the nickname “Superman.”

It has been earned a very hard way as this very successful Marine and businessman has confronted a number of significant life challenges, ones that would leave normal men in the dust.

What follows are the words of Emerson Carr which are captured from our conversation with him earlier this year.

[maxgallery id=”121625″]

Emerson Carr:

I grew up in, in Minneapolis, went to an integrated high school Minneapolis Central, 1963, as all schools were in Minneapolis back in those days. But Minneapolis has always been a very integrated city.

Even in the north, it was a very integrated city.

And I was lucky enough to play on a really spectacular football team when I was in high school. And we were a group of kids — most were black kids and we all grew up together, playing football.

One of my best friends I’ve known since – I we still talk – since we were three years old. We were in nursery school together. And, and as we grew up together, he became the star running back and I became the star lineman.

And when I was in high school, my high school team is still regarded as the best high school team ever in the state of Minnesota.

We were undefeated for two years.

When I was in high school my — we won three state championships, which is pretty unusual. We won two track championships and one football championship. So I was pretty fortunate.

Back in Minneapolis, in the ’90s I was president of a company, there. One of my employees one morning came in and, hey, boss, you grew up here. I said yeah. He said, well, you know, they were talking about you on the radio last night. I said, what? He said this is sports radio and they were talking about the best football players and, and everyone said that you are the best lineman ever in the history of, of Minneapolis football. And that was three years after I graduated. Somebody apparently told them.

When I was in school I had — every week they would have this program, The Lineman of the Week, and in my senior high school I was the lineman of the week every week. And they have a, they have a program on Monday after the weekend that had the Vikings and the University of Minnesota Gophers.

When I was in high school I was a pretty smart kid and I had 50 college scholarship offers. I got 22 and accepted at all three of the academies and, and I chose to go to Naval Academy.

I actually wanted to fly, and I wanted to be in the Marine Corps.

As a kid I always wanted to be a pilot. And, and I did come from a military family. My father was not in World War II. But he had brothers who, who served, and they were all in the Army.

One of them was career Army guy, a master sergeant when he retired.

And so they all wanted me to go to West Point.

Well, actually they all wanted me to work for the post office when I was in high school. I think I had my sight a little higher than that. But I always wanted to be in the Marine Corps and I wanted to fly airplanes, and so that’s why I went to the Naval Academy.

I got drafted out of Navy by a Baltimore coach that we’re all familiar with. Playing the East-West All Star game and I was recruited by a lot of NFL teams who wanted to draft me to come play for them. The Baltimore Colts were really serious.

It came to a point where they even talked to the Navy about it, if I had and I said yes.

I was offered a contract by the Baltimore coach to play football but I was informed that I already have a contract with the United States Marine Corps.

I wound up getting accepted by the Marines, and after The Basic School at Quantico, Ed and I went to flight school at Pensacola.

But classmates who chose the Marines, first had to go to the basic school together to learn how to be infantry Officers which was a good time for all

I remember that the non-academy grads complained about how tough basic school was.

We all looked and said, what, tough?

Timpelake: It’s a vacation.

Emerson: It’s a cake walk.

By the way, you know, the great strength of our basic school, besides our unity, was we got a Commandant of the Marine Corps out of it with General Mike Hagee.

So we were pretty successful at the height of the war which truncated the course. Usually, a basic school is six months. We, we did in five to race us into the end of the Vietnam War. So it was, it was an interesting time for all of us.

In Pensacola, is where the story starts again.

When I was in a flight school, I was number one in my class. I flew A-6A Intruders. After flight school, I went to an A6 squadron. And the, the last year before I got out I switched to C-130s because I thought I wanted to fly for the airlines. I love flying C-130 of the Marine Corps; I thought our C-130 was the best airplane ever built. It might well be. They’re still building them.

In thinking about it, I didn’t want to fly for airlines; I didn’t want to be a bus driver. And so I worked for General Motors. I worked for AC Spark Plug division of General Motors.

I did not have an average career I ended up being promoted several times and I became the global operations manager for all of our ignition and filtration products. Those were all the spark plugs and filters.

I was responsible for our plants globally. I was stationed in London, England. Our American plants and Canadian, French, and Mexican plants all reported to me. That amounted to around 4,000 employees and about $2 billion of sales that I was responsible for.

In those days AC made the entire component parts for all GM cars, and so the company was 25,000 employees around the world. And in Flint, Michigan where I was, we had five different plants co-located with about 13,000 employees and each of the plants was all separate entities within our hierarchy.

There was tinternal competition among all of the managers within those plants to get promoted, successfully from a supervisor to a general supervisor to plant superintendent to a plant manager. But we all knew at the end of the day it was Navy beat Army. That was it.

I could identify with my AC Spark Plug identity. My identity within the company, within the plant I happened to be working in was secondary to my overall identity as AC Spark Plug employee. I’ve managed my operations, to never be in competition with the other members of my plant. I never tried to outdo them. I tried to make sure that my operations were better than our competitors.

I had this focus on excellence and productivity because what was happening, regardless of what my internal numbers might look like. I became so, so successful that I would give away points – I called it points – to other members of my team within the plant, to help them do better.

I kept getting promoted because, in my operations, I really had my employees focused on the externals. That if I was running the filter division, I’d give them a challenge and they would always rise to meet the challenge. Rewards were small but important.

I would tell a department if you guys can run making filters and we have coffee and I’ll buy the donuts. At one point I was buying so many donuts that somebody from manufacturing called me to his office to find out what I was doing “Why are you buying these donuts? “

I explained to her what I had done for my team, while they were shifting through scrap, and it made a difference.

But my team was actually focused on something larger than that. It required a big vision to motivate people and lead people. They all made me successful and it was appreciated. I kept getting promoted and getting better assignments and, became a global operations manager with responsibility around the world.

Affirmative action didn’t exist when we were growing up. And so the people who made it they made it based on their own talents. And there was no suspicion about the gaps in some government systems. That there was a spot open for them because the government mandated one, but everyone had to do it on their own.

I was making a lot of money and I had a job offer to make more than twice as much with an engineering company. I would be president of an engineering company, a division of an engineering company. I moved on to become the president of a company owned in Minneapolis, so my kids got to go back to my hometown.

I was president of the largest engineering firm in Twin Cities in the state. We owned 28 offices in three different states and I became president of the Twin Cities Company. My boss was my old boss from, from AC Spark Plug who I worked for and we had been promoted together. He got promoted to corporate; I got promoted to take his place. I had a very good relationship with him and so I thought this could really work.

I was president of Twin Cities Testing, but eventually the company went bankrupt. The company went bankrupt because of leadership at the top, the chairman of the board didn’t know how to manage an engineering firm and eventually it went bankrupt.

I was then recruited to become president of Champion Spark Plugs. And they wanted me to spend some time as part of one of their operating teams just to get to know all the people there and get acclimated with how they do things in the group.

During that process I had a routine physical and they discovered a lump in my chest. They spotted it in my lungs and after CAT Scans and MRI’s, they found this thing in my chest the size of a tennis ball. I had this thing growing in, in the lower lobe of my right lung.

And I went to the University of Michigan Hospital and they said, you know, this has to actually come out immediately. I said, well, aren’t you going to do a biopsy to determine what it is? They said, nope.

After they got it out a biopsy reported that it wasn’t cancer. It was a fungus that was growing inside my lungs. During the surgery they severed some nerves and I was partially paralyzed on my right side. And so while I was on sick leave the company that had recruited me went bankrupt.

Question: So you’re partially paralyzed. You’ve just gone through a major surgery and the company you’re working for goes bankrupt.

Emerson Carr:

That sums it up. I then started doing business turnarounds and I had a partner who was, who was my finance guy, and I was the manufacturing guy. So the two of us, although we had other guys we could call but it was primarily the two of us.

We’ve got companies to help with finances, and I would do the operations. I would, turn the operations around while my partner turned around the finances

My thing was lean manufacturing.

During this time period, things were really difficult in the auto industry, and General Motors had a number of minority suppliers and they had a minority firm that was doing turnarounds for their minority-owned suppliers. And the owner of that company had been charged with felony.

Consequently, GM was looking for another minority firm to do turnarounds for their minority-owned suppliers. So we were in the running to be that firm which would have been very lucrative for us.

I was on my way to a pre-meeting with my partner and associates before we go to the closing meeting before we were actually hired to do the, do the turnaround. I was going to the meeting in Detroit. I was on my way to the GM Headquarters where our meeting was going to be. And I was on the highway going to the northern suburbs of Detroit when I got hit by a semi-truck going about 60 miles an hour.

Fortunately, I was only five minutes away from the Michigan’s trauma center, William Beaumont Hospital. Apparently, I hit the cement concrete wall backwards which is, was fortunate.

Because, they said if I had gone in head first, I think I would’ve been killed. But I was almost killed anyway. I looked up and said, I made it; that wasn’t so bad, you know.

And then all of a sudden you get flooded with pain. Oh, god. I mean it was the worst pain I had ever experienced. My whole chest was on fire. Just my whole core was just exploding with pain and I passed out. And I came to the hospital and they asked us some questions. I was in and out of consciousness and ended up in a coma for the next couple months.

Let me take that experience and put into context. Ed and I went to SERE school “survival, evasion, resistance, and escape.” The whole school it lasted a week. And part of it is just out in the woods and teaching you how to survive on nothing. You know, you eat grasshoppers or ants and bugs and snakes and rats, whatever you could find out there. And if I would just tell you that, you know, if its protein, if it’s edible, eats it– it doesn’t matter what it is, eat it.

You go into the resistance phase where they put you in a practice POW camp. And for me I felt it was very realistic. They, they piped in Vietnamese music and everyone speaks to you with an accent. You have a hood over your head and you can’t see anything, and it’s pretty terrifying.

The important thing about SERE school and why I want to go back to it is because the one thing they teach us is don’t quit.

And you keep telling yourself that you’re going to survive. The difference between those that survived and those that didn’t was simply the will to live.

And, and as long as you tell yourself you’re going to survive, you will. And they drumbeat that into you while you’re at SERE school, that the only thing that’s important is survival.

You could tell whatever you want to tell them, but you have to survive. And I think that it’s it stood out. If you want to survive this, then you have to will yourself into it. That becomes so important later on in my life particularly while I was fighting for my life once again and this time for real after the car accident.

During the time of the accident we had just moved to Maryland because my wife had a new job offer teaching at a private school in the D.C. area which is where she lived. It was a great job offer, it didn’t matter where we were because, like I said, I was consulting, and I could fly out at any place, you know, to go. At that time, I was consulting in Chicago and, and Kentucky and it didn’t matter I could be headquartered in Maryland.

After the car accident, my wife was flying back and forth between Detroit and D.C. working during the week and flying here during the weekends. And during one of her visits, the head of the trauma section there asked to speak with her for a few minutes.

And he said, Mrs. Carr, “I’d like to talk to you about your husband.” She went through things that I just told you about, my experiences as an athlete and at GM and Marine Corps, pilot, going overseas. She didn’t talk about SERE school because I don’t think she really knew.

“I asked these questions because we really don’t know why he’s still alive.

“But there’s something inside of him that has given his will to live.

“And he might survive.

“He might make it.

“It’s because we don’t know why he’s still alive.”

But clearly in my mind, it was the training that Ed and I both had in terms of not giving up, not giving in

When I finally did get outof intensive care, I remember being visited by the nurses and the doctors. They would come visit me and talk with me they said: You were really remarkable… You could talk. You’re coherent. You understand what, what we say. Usually people we talk to, after they had been there for almost three months, they don’t understand what we tell them. And this is you really? Now people like you don’t come along very often in, in our business and so everybody is just impressed that you’re so coherent.

I came back to Silver Spring and went immediately back to the hospital for another month after I’ve been released from Beaumont Hospital in Detroit. I was in constant back pain and I had to use a walker to, to get around. I guess it was maybe a year-and-a-half later when I went to the doctor and got another X-ray and they discovered a bone spur touching my spinal cord.

So they said, well, we can fix that.

I then had surgery on my lower back to remove this bone spur and after surgery I felt really great. It was the first time since the car accident that I could actually stand up without pain.

I remember my wife and I went to a bar mitzvah. That was all formal. Somehow, I put on my tux; tuxedo and I could actually dance with my wife.

Unfortunately, a few days later, I started feeling bad and I just kept getting worse and worse and worse. And I got to the point part where I feel my back where I had the band aid over my wounds, over the surgery. It was damp and oozing.

I asked my wife to take me to the hospital. And so we went to the hospital and they said it’s infected, we need to do the surgery again. I had another surgery to clear it all, the goo and all the infected material.

I went back to intensive care. I was there for a few days. I never got any better. I still kept getting worse and worse and worse. So it’s back to, back to surgery again.

They did a third operation on my back once again to remove all the goo, all the bad flesh that they missed on the first two. On the second one anyway, I went back to my hospital room and I was doing well. I was discharged from the intensive care unit and went to the regular unit, and I thought I was doing pretty well.

And I think a day or two later a doctor came to see me and said; we’re taking you back to intensive care immediately. And I said, well, what’s wrong? He said, “we’re monitoring you and you’ve had three heart attacks and we don’t know why. We don’t know what’s going on here.”

It was an MRSA infection.

They started me on cipro which, which worked, for the next six weeks. I was transferred to a nursing home where I had cipro 24 hours a day for the next six weeks to try and kill the MRSA, and it did. I got out just in time for Christmas.

I was pretty confident that I was going to beat this. I was pretty positive my attitude was good, that this is going to end, however, I was wrong.

I was wrong. The MRSA was, was still, and was still there, the following summer it attacked my heart and my heart stopped.

I was leaving my house on my way to the drug store. At that time, we lived in a townhouse and so I was going out down our back driveway where all the other townhouses had their garages I was sitting in my car and felt bad. I drove back home and I got out my car and I passed out.

I remember falling flat on my face and cracked my glasses and hit my head. I don’t know how long I was out, but when I woke up, my head ached and there was blood right down my face. And I got up to go in the house, and as I was walking and I passed out again. I hit my face on the concrete again, and I crawled inside the house and called friends come pick me up. I went to the hospital and they called my wife.

The police came, and interviewed me about what, what happened. I tried to explain to them what happened they understood that there was a medical condition and that, that I was passing out. I was then talking with my wife who was at a room while talking with her there was a nurse, and I passed out again My wife saw the nurse raise his fist and hit me really hard in the middle of my chest and nothing happened. He felt for a pulse and there wasn’t one. He pushed the blue button. And the register doctors rushed in with a crash cart and asked her to leave.

They put the defibrillators on my chest, everyone stands away and, and they kept doing that a few times to get my heart going again.

My wife asked: “Doctor, can I ask you a question?” She said, “What was so funny? I saw everyone laugh. What were they laughing about?”

He said, “Oh we have – when, when he came through, we asked him who he was, what, what’s his name, and he looked around the room, kind of groggy and said superman.”

Ever since, every Christmas I have tree ornament that’s a superman. So, this year I looked at all the different superman’s hanging in my tree.

I’m on my way home from the Hospital and I call home I think I’m doing okay. You know I’ve difficulty, yeah, breathing. I was temporarily on oxygen but after I got home, but it only lasted for a while. It went off actually.

I was up in the middle of the night one morning and, and I was so nauseous and I started throwing up, and I was throwing up, it was all red. And I looked in the stool, and, and you know it was just bright, bright red. And so I woke my wife up said I need to go to the hospital.

There’s something wrong.

I went to the hospital and they found I had a bleeding ulcer, that wasn’t that big a deal. It’s just bleeding ulcer. There’s nothing they can do about it, I got better and I was released from the hospital.

In 2014, four years ago, I went to visit my, my mother in Minneapolis, who was at that time 90 and was dying. She had vascular dementia. I was back in Minneapolis for the first time in a long time, and I remember waking up and it was 14 below zero. I could not believe how cold it was. It was14 below zero, at 10:00 in the morning, bright and sunny.

If you ever spend some time in Minneapolis, a lot of time, the morning time is beautiful in Minneapolis; Bright blue skies, you know bright sunshine, but very cold.

I flew back home, and the next day I just wasn’t feeling well. I had stopped breathing.

She started giving me CPR and called 911. 911 came and they took me to the hospital, and I was hemorrhaging. I had internal hemorrhaging and they transfused ten units of blood. And so I just barely survived that and they never discovered why. They were going to but then they opted not to do any surgery, for they were not certain what was happening.

I had a physical therapist that would come to my house to help me because I was in the hospital for four weeks, and then a rehab center for another four weeks and I had trouble breathing. I had to go on oxygen.

I’m still on oxygen, and you would think the story would end there but it doesn’t. I’m still having a couple of episodes. There, there is one episode where I was in, in the hospital it wasn’t for anything particularly serious but, but I was given pain pills, and when I get pain pills I get, I get constipated.

And I got constipated to the point where, you know, I, I begin to have an edema and I’m beginning to ball up. Looks like I was pregnant and it became serious when they called in surgeons. And the surgeon came in and said, “we’re going take you to surgery and we’re going to remove your colon. Because we can’t afford to have it burst in and, you know, infect your bloodstream and you’ll get sepsis and it will, it will kill you. So we’re going to take out your colon.”

And another doctor who was standing nearby said, “Jim, before we do that, I know a drug that might be one last chance. It’s similar to what we use to make muscles contract when someone’s face is paralyzed. I want to give that a try.”

He said that If that doesn’t work in ten minutes, we’re going into the operating room. They gave me the drug and fortunately it worked. Ten minutes later, I was much better.

I had my birthday party a couple of days later. I’m not feeling well. I have a stomachache, stomach cramps. My stomach hurts, my side hurts. I gave it another day. and it just got worse.

The next day I said I got to go to the hospital. This is too much pain. And so I went to the hospital, and they discovered I’m having appendicitis. My appendix has ruptured, and they needed to take out my appendix.

The doctor, the surgeon said we have to take out the appendix. Another doctor said, “Hmm, I don’t think so. I don’t think we could do that. Well, frankly, if, if you – if he goes on a ventilator, he’ll never come off.”

One group of doctors says we have to take it out. It’s already ruptured. He’s going to die if we don’t take it out. Other doctor says you can’t operate because he won’t recover. He will never recover consciousness. He will be on a ventilator for the rest of his life.

I can’t survive a normal surgery I would end up as a vegetable, on a ventilator forever that was the situation I had.

Either have the surgery, take it out, and take the risk or don’t, and we’ll give you antibiotics and constipate and hope that it works. I said, “Well, I don’t want the surgery. Let’s just go with antibiotics.”

But it just kept getting worse. My fever got worse. I passed out. I was unconscious.

I can remember dreaming when I was unconscious about being back at the Naval Academy at swimming class –– at 8:00 in the morning and jumping into the pool.

As you jump in, you’d be smothered by ice water and all these bubbles as you came back to the surface.

And so that’s what I visualized while I was in the hospital, fighting this infection and this ruptured appendix. I was jumping into this ice-cold water and being surrounded by oxygen, oxygen bubbles and floating back to the surface.

That visual image is what I thought about. And I kind of surfaced and I opened my eyes. And I’ve come back. And so whenever I was – I can see myself beginning to pass out, I’ve, I’ve switched my thoughts to that image of me underwater, surrounded by bubbles, and coming back to the surface.

And I open my eyes again.

And so I think it was that imagery of surviving that that kept me alive. And eventually, they did do kind of minor surgery to drain the abscess in my abdomen. I survived it just with the, the antibiotics.

I was in the hospital for a month, another month in rehab and then recuperation for the, for the next year. And so that brings us up to today.

I sure think of myself as who I’ve been all my life. And we have a significant setback.

But I still see myself as a very successful, very competent human being with more to offer.

I’m not done yet.

And I’m not sure what the next chapter’s going to be.

Em Carr is a person that personifies Faulkner’s immortal word:

“I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail.”

Editor’s Note: A Navy Sports story published October 31, 2011, focus on the stories of Calvin Huey and Emerson Carr and that story follows:

Last winter when the Navy Midshipmen were polled by their coaches to name a new pair of captains, the easy choice for the defense was Jabaree Tuani.

“The perfect defensive captain,” his once and again teammate, in high school and at the Naval Academy, Mason Grahamdeclared.

Not that it mattered as they cast their votes, nonetheless his fellow Mids paid Tuani the same level of respect he earned in his prior life as a student attending at a small, private school near Nashville, Tenn. There, at Brentwood Academy, the popular Tuani was elected the school’s first African-American class president.

“I was at a predominantly white high school, but it didn’t bother me at all,” Tuani says. “I got to know everybody on a personal level.”

They, including Graham, did the same; ignoring the meaningless obvious for the only thing that matters when judging another. It was no different four years later.

And no surprise. The Midshipmen were here in the first place because of the content of their character. From the shades of their skin to the syllables forming their family names, they’re representative of an increasingly diverse Academy.

Descendants of the Far East, Latin America, the Pacific Islands and numerous other latitudes and longitudes, they consider themselves a Brotherhood. As teammates, race and ethnicity are irrelevant.

They serve under a Commander-In-Chief, Barack Obama, who is our first African-American president. Often they train inside a state-of-the-art facility named in honor of the Academy’s first black graduate, Wesley Brown.

More than any other player, save for fellow captain Alexander Teich, Tuani speaks for them. His is the voice that resonates from their locker room to Bancroft Hall to the ears of those outside Academy walls. He is their team leader in a 21st Century Annapolis.

But less than a half century ago, this was a very different place and Navy football had a very different look, because the Mids all looked the same.

While Brown graduated in the Class of ’49, it wasn’t until 1964 — 17 years after Jackie Robinson debuted with baseball’s Brooklyn Dodgers – that a player of color played for the Blue and Gold.

Recently, Tuani was quizzed about that football predecessor, a son of the South, who blazed a trail to Annapolis. An inquiring mind wanted to know if he’d ever heard of Calvin Huey. Tuani had not.

In fairness — and full disclosure — neither had the individual who posed the question; at least not until the most recent week or two of a 15-year tenure covering the Midshipmen. Nor had his broadcast partner from the Navy Radio Network, Omar Nelson, a ’97 grad and former USNA instructor particularly close to many players of the last decade.

The same was true in May 2008, when Frank Simmons returned to his alma mater for the dedication of the Wesley Brown Field House. Recognizing a prominent member of the Mids, Simmons pulled the young man aside and asked: Do you know who Calvin Huey is?

As with Tuani, Nelson and this writer; if Huey’s name rang a bell, the significance of the man and his accomplishments didn’t quite reverberate. That’s when Simmons made it his mission to educate the rest of us about Huey, as well as Emerson Carr; two individuals as important as any in Navy football history.

Simmons was commissioned with the Class of ’68. When he entered the Academy, blacks within the Brigade included three seniors, no juniors and two sophomores. He was one of seven minority plebes, among the four to graduate.

Working as a program manager for SAIC, the Fortune 500 defense and security contractor headquartered in McLean, Va., Simmons recently found time to act in the names of Huey and Carr.

“One day at work, a couple of months ago, I thought, ‘This is the day I’m going to do it,'” Simmons said. “Today I’m going to send an email to (Chet) Gladchuk.'”

His message to the Academy’s athletic director led to the words that follow, about two men whose college choices are watersheds in the 131-year history of Navy football.

Calvin Windell Huey grew up in Pascagoula, Miss. He was 19 years old when U.S. Marshals were ordered to his home state to enforce a federal court order allowing black student James Meredith to enroll at the University of Mississippi.

Influenced by uncles who schooled him in math, and a mother who enrolled him in summer programs at Historically Black Colleges, Huey was a gifted student. He was especially interested in science, specifically chemistry.

“My hope after high school was to go the University of Chicago, Ohio State or Wisconsin,” Huey recently said from his Annapolis home, before laughing. “Unfortunately, I didn’t know you needed money to go to those schools.”

He attended Tuskegee briefly, but left to join a friend at Oakland City College in California. Leaving the segregated South to go West, Huey was eventually lured East.

At Oakland, he was honorable mention junior college All-America as a quarterback. Recognizing Huey’s aptitude and athleticism, a friend suggested he pursue a service academy appointment.

Huey contacted Mississippi representatives. As you’d expect, he was immediately denied. One congressman, he remembers, reasoned that he didn’t want Huey “to be a stain on Mississippi.”

Undeterred, he instead got a California representative to nominate him; not as a football recruit, but solely on his own accord. In fact, Huey says he had no contact with Navy’s coaching staff before trying out for the team as a plebe.

Contrastingly, Emerson Frank Carr was being courted by all three academies, and numerous other programs, while enrolled at Central High in Minneapolis.

“I was the biggest guy on our team,” says the 6-foot-3 Carr, whose media guide bio listed him as a 235-pound defensive end entering his senior season with the Mids. “And I’m proud to say, also the fastest. I used to beat our receivers in wind sprints.”

West Point, which wouldn’t suit up its first African-American player until 1966, was the first to call on Carr. But yearning to fly, he was more interested in the Naval Academy.

A year after Huey reached Annapolis, Carr followed, becoming the first black Minnesotan to attend a service academy.

Hailing from the North Country, Carr makes light of his mostly pale surroundings in the Twin Cities.

“I went to what was considered a predominantly black school in Minneapolis, (but only) 20 percent of the students were black kids,” Carr says, before showing off his sense of humor. “You could also say the non-Scandinavians were the minorities. I thought the whole world was made up of Andersons and Johnsons.”

Regardless, Minnesota was very progressive. Unlike the city of Annapolis, where public schools remained segregated until 1966, more than a decade after Brown v. Board of Education. Carr found certain restaurants and movie theaters off limits.

On the other hand, Huey was accustomed to such racial demarcations. Sitting below the Mason-Dixon Line, Annapolis was, he remembers, “very much like Mississippi.”

Huey makes the comparison absent the slightest tinge of bitterness or resentment. Same goes for Carr.

Though outside the Academy, the Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum. Inside, Huey and Carr were simply trying to succeed as midshipmen.

“The March on Washington took place during my plebe summer,” Huey recalls. “I didn’t know it occurred until a year after.”

That’s because he concerned himself only with what he needed to know to satisfy the demands of upperclassmen. If skin color subjected either to extra harassment, neither was aware of it.

Huey actually thinks he had it easier than most by trying out and making the basketball team, as well as the football squad. Sports enabled him to dine with teammates, instead of answering to older shipmates.

“I think I pretty much had a free ride by being an athlete,” he says. “I wasn’t dumped on as much as other midshipmen because I was playing sports. I had no trouble until the end of the year, because I ate at the training table for football and basketball. I joke that I had a two-week plebe year.”

More than likely, fellow mids simply reciprocated the way Huey conducted himself.

“It was important for me to be as respectful as possible,” he says, “and try to be an exemplary midshipman and person.”

“I don’t think I was treated differently than anyone else,” adds Carr, who was too busy making history to consider his place in it. “After the fact, one of the things you became aware of is being a trailblazer.

“The people who really pulled me through are my classmates. My classmates treated me like one of them.”

Coaches did too, namely three assistants. Carr remains thankful for the tutelage of Carl Schuette; the way Lee Corso “took (him) under his wing;” and the equal-opportunity demands of Steve Belichick.

To Belichick, the only time to see anything as black or white was on the practice field. Things were either done right or wrong; no in-between. But there was one problem that still causes Carr to chuckle: Belichick could be too indiscriminate. Sometimes, players couldn’t distinguish among themselves.

“Steve had the ability to look at the entire field and see everyone at the same time,” Carr explains. “He was the linebackers coach. He would be yelling at someone during practice, but we weren’t sure who he was yelling at. You couldn’t tell from his eyes. We’d turn to each other as players and ask, ‘Who’s he talking to? Was that you or me he was talking to?'”

There was little to nitpick about Carr. In Navy’s 1968 media guide, Schuette said Carr had “exceptional talent, speed and quickness…all the attributes to be one of the East’s leading defenders.” His words held true when Carr was invited to the East-West Shrine Game.

Meanwhile, Huey was singled out in his senior-year bio for “poise under fire,” as “an outstanding pass receiver and determined downfield blocker.” Though a quarterback at heart, he moved to receiver to become a catching complement to the passing of Roger Staubach.

In the autobiography Staubach: First Down, Lifetime to Go, the ’63 Heisman Trophy winner wrote: “Calvin Huey was just the kind of guy you liked. He had a great personality, worked hard in football and was an intelligent guy.”

Smart in the classroom, Huey was also savvy on the field.

Shrewd enough, at least, to improvise what for a fleeting moment or two had the makings of one of Staubach’s most memorable plays.

Facing a late deficit vs. Maryland in 1964, Huey subbed for one of Staubach’s favorite targets, Skip Orr. As the clock eclipsed the 3:00 mark, Huey caught a 10-yard touchdown pass for the lead.

“I actually called that play,” Huey says. “Roger would sprint out to the right and the Maryland defense would flow with him. I suggested he do a half roll, and throw back to me.”

Unfortunately, in the immediate aftermath, Ken Ambrusko’s 101-yard kickoff return lifted the Terrapins to a 27-22 victory.

“On the ensuing kickoff, my classmate Bob Havasy fell and hurt his knee,” Huey says of his good friend. “Whenever I see him, I joke that I would have been a hero if he hadn’t gotten hurt.”

Punchlines aside, Huey was already heroic. Not by making touchdowns, but by creating touchstones for future generations.

The following year, as a junior in his final season of eligibility, he became the first African-American to take the field at Georgia Tech. Though Navy fell, 37-16, Huey’s monumental afternoon in Atlanta was incident free. Interestingly, the only insults he remembers hearing in a game were hurled much farther to the North, at Penn State.

Likewise, there were times Carr stood apart from teammates and opponents alike.

“We played at a number of Southern schools,” he says. “Often I was the only black player on the field. It’s not something you think about while you’re playing.”

Only decades later. Like when Huey reflects on the game he cherishes most as a Midshipman.

“Army was the most incredible experience,” says Huey, despite the apparent emptiness of a loss and a tie in two varsity appearances opposite an arch rival. “It was the shortest game of my life. It goes so fast.

“I think the Army-Navy game is the thing I’m most proud of. You’re on the field and you know that countless eyes are looking at you.”

Imagine what it must have been like seeing Navy’s lonesome end in America’s game. Especially for people still denied basic rights

Less than a year earlier, states ratified the 24th Amendment to the Constitution, outlawing payment of poll or other taxes intended to marginalize blacks during federal elections. Just five months earlier, Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

And fewer than four months earlier, the bodies of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were found buried together; weeks after they disappeared while protesting, as part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer.

“There was a lot going on in the 60s in the Civil Rights Movement,” says Carr, who originally was a year behind Huey but later spent another full year away. “I went to Annapolis before black people could vote in Mississippi.”

And now, if you will, picture the misguided congressman worried about Huey leaving a stain on the state of his birth. How might he react were he to learn what became of Huey? Or, for that matter, someone like Carr?

They are men of distinction less for what they did as football players than for what they’ve accomplished since.

Huey graduated in 1967, and was eventually assigned to the USS Perry in Mayport, Fla. Before long, he deployed on the first of his two tours of Vietnam. He then continued his education until earning a Ph.D. in Chemistry.

In 1973, he joined the faculty at the Naval Academy, combining classroom instruction with coaching what’s now known as ‘sprint football.’ Back in Huey’s day, it was ‘lightweight’ or ‘150’ ball. By any name, he thoroughly enjoyed it.

After his third year back, former teammate Tom Leiser persuaded Huey to join him at IBM. He remained with Big Blue until 1997, when health problems resulted in a kidney transplant. Fourteen years later, Huey’s nephew donated a kidney for a second transplant.

Carr also has endured health problems since transitioning seamlessly from military service to civilian success.

He fulfilled his lifelong goal to fly, piloting an A-6 Intruder and C-130 Hercules in the Marine Corps. Among his closest friends is ex-squadron mate Major General Charles Bolden, USMC. Bolden graduated from the Naval Academy in 1968, 41 years before becoming NASA Administrator.

An engineer, Carr retired as a Captain and joined General Motors in 1984. In year six, he was promoted to global operations manager for the company’s subsidiary AC Spark Plug, overseeing more than 4,000 employees in North America and Europe.

Much of Carr’s post-military life was spent in Michigan, though he briefly lived in England, where he also studied at Oxford. But by 2004, he moved to Silver Spring, Md. and was a partner in a consulting firm.

Back in the Detroit area on business, Carr was driving to an early-morning meeting when his vehicle was hit by a semi-trailer.

“It was,” he says, “as serious as it gets.”

For two months Carr was on a ventilator. His rehab continued for weeks thereafter, only to be set back significantly by a staph infection. He suffered multiple heart attacks, received a pacemaker and redoubled his rehabilitation program.

However grave his situation, Carr fought through it. At one point, his doctor at the Beaumont Trauma Center in Royal Oak, Mich. approached Carr’s wife, Anita, to detail her husband’s background. According to Carr, his medical team was astounded that he survived.

“‘He’s been trained to fight and survive,'” says Carr, repeating the doctor’s line upon learning of the Marine’s remarkable career. “‘That’s the reason he’s going to make it.’

“Going to the Naval Academy and being in the Marine Corps can have that impact. It impacts you in ways you don’t realize.”

One of the ways most obvious to both Huey and Carr is the ceaseless support each receives from classmates, as he wages his battle against health problems. For Carr, the fight includes a bout with lung cancer.

“The Naval Academy creates bonds that last for a lifetime,” says Carr.

They include ties to successors such as Tuani, who expresses a desire to learn more about the men who opened the door for African-American players in Annapolis.

“I definitely would like to find out more, knowing the adversity those guys had to face,” Tuani says. “They didn’t let it bother them…Nothing could have told those men to quit. I couldn’t imagine not being able to hang out with my friends in public places.”

Not so long ago, the idea of a black kid from Mississippi attending the Naval Academy was unimaginable too. Except to Calvin Huey.

“It makes me proud,” Huey says. “I don’t brag about, I cherish it. My wife (Deborah) brags about it.”

Chuckling, Huey describes how he is is still recognized in Pascagoula. There’s a Hall of Fame inside the technical school that replaced his old high school. He’s included, of course; a plaque there denotes his Academy achievement.

Both Huey and Carr came to Annapolis seeking a higher education, and willing to answer a higher calling to a country whose citizens stood on uneven ground.

By attaining the former and fulfilling the latter, they did their part to impact the Civil Rights Movement in ways they probably didn’t realize at the time. All these years later, it’s about time we all realize it.

“Every African-American my age was affected by Martin Luther King and the struggles of people who died, like four little girls in church on a Sunday morning,” says Carr, alluding to the Sept. ’63 bombing of a Birmingham church. “You have to be impacted (by that). I wasn’t riding the bus, but I was doing something other black people weren’t doing.”

“In a very small way, yeh,” Huey replied, his voice breaking up, after being asked if he made adifference for other African-Americans. “It gave people hope they could do the same thing.”