Brendan Sargeant on the Strategic Shift Facing Australian Defence Strategy

After the recent Williams Foundation Seminar which focused on the evolution of Australian defense capabilities and policies, I had a chance to discuss the changing context for Australian policy and the challenge of reshaping the Australian policy approach with Brendan Sargeant.

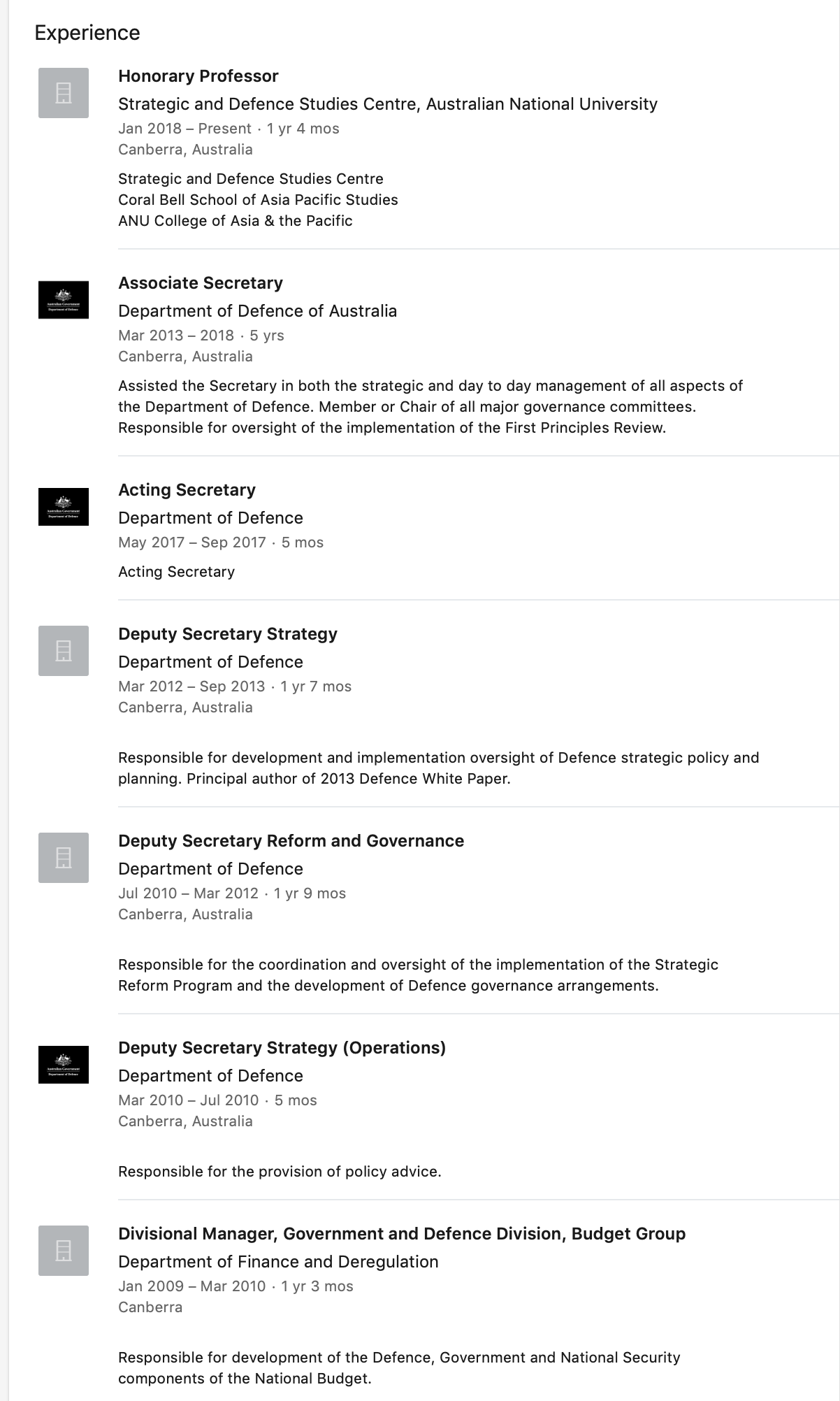

Sargeant is currently Honorary Professor at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, at the Australian National University and has had a long period of service to the Australian Department of Defence, most recently serving as Associate Secretary in the Department.

The key challenge to shape and execute a nation’s defense policy is to understand the priorities, to shape capabilities which can meet those priorities, as well as understanding the limits facing a nation in terms of its resources and its capabilities. It is is also crucial to shape effective approaches to managing that policy in times of crisis, which is a combination of capabilities as well as having skillful leadership.

For Australia, this means refocusing its policies upon the challenges in its region, which is one with global reach.

We started by discussing the changing strategic context. With the rise of the 21stCentury authoritarian powers, and the various dynamics of change in Europe, and in the United States, obviously Australia’s policy approach over the past two decades was no longer valid.

Australia has focused its efforts to contributing the United States leadership in providing for enforcement of a rules-based order, and doing so with enhanced capabilities, but within the context of enforcing an order, not shaping it.

Indeed, the 2016 Defence White Paper underscores throughout the need to enforce the rules-based order. But the 21stcentury authoritarians have no intention of operating within those constraints and are seeking to reshape global order to their advantage.

As Sargeant put it: “The world we have assumed is not necessarily going to be the world of the future. So how is Australia going to live in that world and play its role?”

He noted that the Chinese were seeking to reshape the global order. “The Chinese strategy is clear – guarantee access to resources, create buffers, break alliances and not be constrained by any rules-based order that they do not consider congruent with their perception of their interests.”

He argued that we are facing a fluid period of global change.

“We will see lots of experiments, and see lots of ideas and you’ll see states trying out different political and architectural formations to meet their interests.

“We’re in a world with we don’t know what the future strategic order is going to look like, or how it’s going to be managed. The global order is clearly in play.”

There are cross cutting forces at play.

“Globalization has unleased one set of forces; the rise of nationalism another set of forces; and the rise of the illiberal powers yet a different set of force. Nations are trying to work out how best to protect their interests and with whom to work to do so.”

This has a significant impact on the inherited alliances. There is the habitual cooperation which has underlaid the Western Alliances and that cooperation is continuing but in the context of significant redefinition of what alliances are going to look like going forward,

“Great powers like the United States are more interested in totalizing alliance arrangements than their alliance partners are likely to accept. Australians like other regional allies of the United States will seek working arrangements with a variety of regional partners to provide for our interests and work through different sorts of working arrangements to deal with our strategic challenges.”

The shift is clearly from followership to engagement in working relationships where leadership is shouldered or shared differently from the great power followership role which Australia has followed first with Britain and then with the United States.

Working relationships with regional or global partners around specific issues and challenges are becoming “the real alliances. They are being built in response to specific crisis or specific problems.”

For Australia, the challenge will be how to deal with global and regional crisis management. For defense, this means shaping capability which can be leveraged in a crisis and effectively used by political leadership effectively to meet the national interest.

This means taking a hard look at the kind of defense force which Australia has and is developing and determining which tools are available to decision makers.

It also means building a more durable and sustainable force through a crisis period.

“The ability to deploy force creates more decision space in a crisis. But you need to do that over time. That requires a robust logistical and industrial base that can give you more confidence that you can scale up during a crisis.”

“From a policy perspective, you want to give yourself more strategic options by giving yourself more time. Which means that you will need to have a more sustainable force during a crisis.”

And the crisis management challenge requires thinking through partnerships and working relationships with allies.

“When do you exercise leadership? When do you exercise followership?”

An example of how force packaging might be reworked in terms of partnerships in the region could be the working relationship between Australia and Indonesia.

“We ought to be able to put together an integrated task force with Indonesia to manage a regional crisis from the low end to the high end. And a task force where either Australia or Indonesia could take the lead.”

In short, for Sargeant, “We need to think differently about our position in this part of the world and how that may drive our thinking about the capability which we need to have and to develop going forward.”

http://bellschool.anu.edu.au/news-events/news/6443/radical-new-defence-policy-brendan-sargeant

Australian Defence Policy in Flux: The Perspective of Brendan Sargeant