Scott “Shark” McLaren on F-35 Sensor Fusion

It’s clear that combat capabilities and operations are being recrafted across the globe and, as operational contexts change, the evolution of the role of fighters is at the center of that shift. This year’s International Fighter Conference held in Berlin provided a chance to focus on the role of fighters in the strategic shift from land wars to higher intensity operations. The baseline assumption for the conference can be simply put: air superiority can no longer be assumed, and needs to be created in contested environments.

Competitors like China and Russia are putting significant effort into shaping concepts of operations and modernizing force structures which will allow them to challenge the ability of liberal democracies to establish air superiority and to dominate future crises.

There was a clear consensus on this point, but, of course, working the specifics of defeating such an adversary brings in broader concepts of force design and operations. While the air forces of liberal democracies all face the common threat of operating in contested airspace, the preferred solutions vary greatly from one nation to another, so the conference worked from that common assumption rather than focusing on specific solutions.

The coming of the F-35 global enterprise is a clear force for change. In one presentation, a senior RAF officer outlined how the UK would both contribute to and benefit from the F-35 global enterprise. “The future is now,” he began, as he laid out how he saw interactions among F-35 partners in shaping common and distinctive approaches to air power modernization driven by the introduction of the F-35.

Echoing the “future is now” sentiment, former Chief of Staff of the RAAF and now Chairman of the Williams Foundation, Geoff Brown, provided an overview of how the selection of the F-35 and its introduction in the force is part of a significant shift in the Australian Defence Force to a fifth-generation force. The retired Air Marshal argued that buying an advanced plane and “getting on with it” is both crucial and cost-effective. “70% of your cost is about maintaining, supporting and modernizing your airplane. Why would you want to do that with a legacy jet when you can buy a fifth-gen jet?”

A senior USAF officer involved with F-35 integration highlighted the efforts in working integration both on the level of the MADL-enabled F-35 force, and that force with the legacy force. His baseline point was that the F-35 is operating globally now, and that the USAF is working with its service and global partners on both the ability of the F-35 as a unique fleet to operate together as well as through its link capabilities, notably generated by the software designed and enabled CNI system to work with other assets as well.

He affirms it is clearly a work in progress and that the “sensor fusion” of the force is in its infancy, in terms of being informed by, and driven by, the F-35 as a combat aircraft. In his words: “The aircraft works well in terms of sensor fusion,” and says they are focused on “the journey to mature its effects as an air system on the overall force.”

Scott “Shark” McLaren, an experienced USAF test pilot, explained what sensor fusion means to the combat pilot. The combat-proven F-16 pilot had shifted to the F-35, and ably addressed the core question of: What does situational awareness look like for the F-35 pilot, and what does it mean for his combat prowess?

In simple terms, the 4th generation pilot fuses the data from his on-board systems to operate against a specific combat task, and is dependent on what his network can deliver in terms of broader sensor fusion.

The F-35 pilot, on the other hand, has SA provided from sensor fusion machines on-board his aircraft rather than having to rely on networks and he focuses on shaping tasks crucial to missions in the combat space. That pilot can then work with the integration from the unique data network provide for the low observable jet through the MADL data system to then operate as a core combat force. The cluster of F-35s can then provide networking enhancement to other aircraft in the force or, when low observability is not the primary requirement, can leverage broader networks.

What becomes clear, is that the evolution of legacy fighters (mostly referred to as fourth-generation) is a key part of the evolution of the response to operating in contested airspace. This is a major focus of attention for any of the air forces introducing the F-35, and is clearly of concern for a legacy force like the French Air Force which does not intend to buy an F-35.

The question becomes, how will the different legacy fleets adapt to the F-35, and what will their tactical and strategic contributions be as they adapt to the evolving strategic environment? There is also a key dynamic of change for what are referred to as the “big wing” aircraft such as AWACS and the various ISR aircraft. Generally, there is a major shift in how command and control (C2) will be done as fighters and their connected brethren work together to deliver the desired effects in the 21st century contested battlespace.

After his presentation, I had a chance to sit down with “Shark” and discuss his experience transitioning from the F-16 to the F-35.

The baseline point is that the designers of the F-35 cockpit based on their experiences with the F-16 and the F-22 worked to provide for a visual and work system that significantly reduced the pilot load.

Then with the integrated sensor system built into the F-35 the role of data fusion is to provide situational awareness as a service to the pilot and the MADL linked combat force.

This is in contrast to a legacy fighter where the pilot is fusing the data up against a core task such as air superiority or ground attack.

In contrast, the fusion system “engine” leaves the F-35 pilot with more flexibility to perform tasks as well as operate in the words of the USAF speaker in the first morning of the conference to provide for strategic inputs as well.

“Shark” described his experience as an F-16 pilot as fusing the data from the various screens within the aircraft.

“The radar will be on one display; the targeting data on another.

“Perhaps a picture generated from the Link-16 network on another.

“You are now focused on a particular mission and putting together that data up against the core mission for which your aircraft and the formation is dedicated to executing.

“The human brain is where the information on those separate displays are being fused and translated so that pilot is able to execute the mission. And he might also be working his radio to coordinate the mission as well.

“And this is being done in a high speed combat jet where if there is a pop-up threat you might need to refocus and deal with that as your focus of situational awareness.”

The training cycle for our proficient F-16 pilot according to Shark is around 24 months to go from basic flight skills to formation flying, to learning the different mission sets and getting comfortable with delivering weapons or an effect in the different mission set environments.

And over time, as the experienced pilot flies more missions he can shape the mental mission profiles in his brain to guide the various combat missions with other combat aircraft.

“Over time, those years that I’m talking about, he’ll be able to build that mental picture, that mental model, and do most tasks, take on more responsibilities so that he can lead a two-ship, a four-ship, an eight-ship- whatever the case may be- and have enough of a mental model, based on the information coming in, to execute the mission.”

Shark added that the role of the radio is important in working the execution of missions onboard the F-16 as well which is also part of the demand side on the pilot’s attention and thinking process.

“A lot of what’s done in side a fourth-generation aircraft is done over the radio.

“That’s why I have other players maybe command and control, other tactical players that are sending me information over the radio.

“Audible communication.

“There’s no hand gestures that I can use for seeing body language, nothing. It’s just the communications that’s said over the radio, or heard over the radio.

“And now you take more time, you ask questions. And all the time that you’re doing that, that mental picture that you were supposed to be building? Your mental picture is getting disrupted.

“So when you come back to it, where is that mental picture?

“You’re probably going to drop out some of it, some of that mental picture. Some of the best pilots could keep track of it. And keep track of it pretty well.

“But even then, some of the information has dropped out.”

With this as the notional baseline, “Shark” then described the significant difference which the F-35 systems and sensor fusion can provide the pilot and the combat group.

“With the F-35, this is where the operational capability changes.

“With the F-35 you have automation via fusion going on.

“That process that is taking the F-16 pilot years to get good at, and almost all of a notional ten-minute engagement time to build a good picture, is being done automatically for the pilot in F-35 fusion.

“That picture is being built. In that same ten-minute scenario, it’s taking less than a minute for all of that information to be presented to him.

“He knows the picture.

“And that’s without any communication having to go across the formation.

“Your mental processing power which in the F-16 is focused on creating the operational mental picture or SA is now focused on combat tasks and missions.

“Your training focus also changes.

“Rather than focusing significant training time on how to shape your SA picture, you can now focus on tasks in the battlespace and distributed operations.

“The Commander and the F-35 force can focus on the effects they want to deliver in the battlespace, not just with themselves, but by empowering other combat assets as well by sharing the SA through targeting tasking.

“We have the capacity to third party target and to distribute the effects desired in the battlespace.

“That becomes our focus of training and of attention; not a primary focus on generating the SA for my organic asset to survive and to deliver a combat effect itself.

Using Shark’s 10 minute operating paradigm where the F-16 pilot is spending 8 minutes of that time period on SA and mission preparation, the F-35 pilot can spend 9 minutes of his time on mission preparation and distributed operations if so tasked.

Shark concluded: “For the F-35 pilot, training will now need to include how you go out and influence the battle area the best for the commander?

“And that’s going translate up to what the commander needs to give in direction, but also back down to what the pilot needs to know.

“And that training is part of a larger joint exercise, a larger concept of operations for the joint force which gets at the strategic impact of the F-35, which the USAF BG discussed in the conference.”

The International Fighter Conference 2018 was held from November 12-14 2018 and was organized by IQPC Germany.

Next year’s conference will be held from November 12-14 2019.

The featured photo shows Test pilot Scott McLaren launching an AIM-9X air-to-air missile during weapons surge testing. (Photo by Jonathon Case/Lockheed Martin).

For Ed Timperlake’s look at the role of combat pilots in the roll out of a new generation of combat aircraft, please see the following:

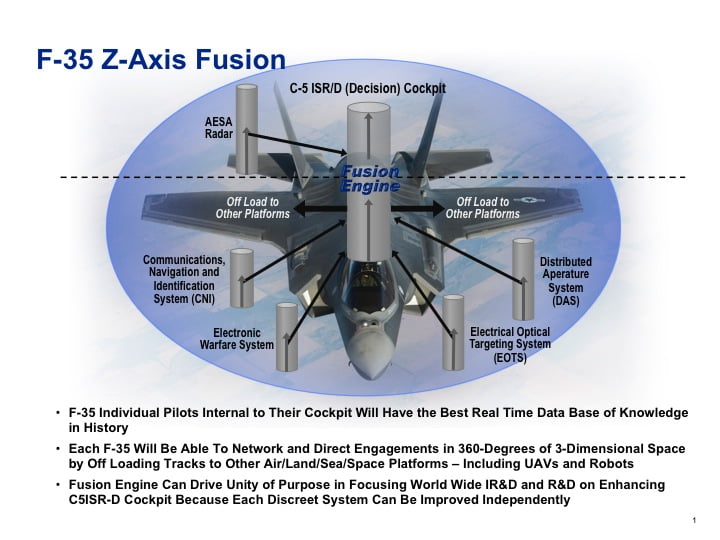

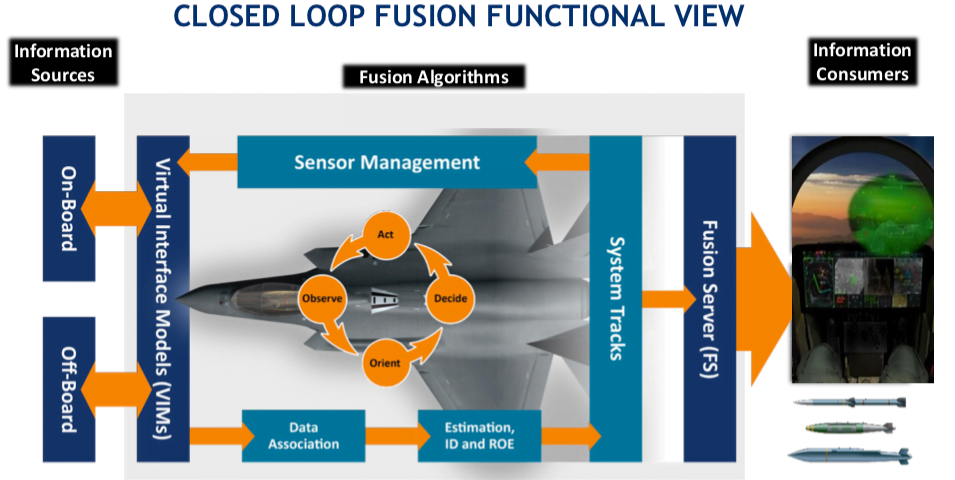

Ed Timperlake also addressed the fusion engine in the following article as well as graphic:

The F-35 as a “Flying Sensor Fusion Engine”: Positioning the Fleet for “Tron” Warfare