Situational Awareness and Gray Zone Conflicts

As Western militaries finalise the long and slow withdrawal from counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations in the Middle East, an even more complex problem arises: the problem of re-calibrating operational risk for activities below the threshold of conventional warfare in ‘grey zone’ competition.

While the enemy in the deserts and the mountains chose to avoid direct conflict, the type of adversaries we may face in the future could even choose to deny the very existence of a conflict. We must therefore seek an advantage through superior decision-making, and that advantage relies on understanding what is happening in both the physical and the virtual operational domains.

Grey zone conflict is nothing new – politics and war have always existed on the same continuum. But the new problem is that success in the grey zone depends on our understanding of a situation, not just awareness. Situational awareness is a dynamic, tactical phenomenon typically associated with the physical world, whereas situational understanding provides an insight into the broader asymmetries and intent in the grey, multi-domain battlespace.

Situational understanding has strategic value: it buys you time and space in all domains and originates from intelligence collection operations which enable the application of national power in precise, targeted times and locations. This national power may be military, it may be diplomatic, or it may be economic. But in each case it requires knowledge, and it is the getting of this knowledge that carries the operational risk.

Yet history has shown that operational risk associated with intelligence collection has a habit of rapidly exploding into political and reputational risk. Poor operational risk management manifests itself as strategic surprise, which immediately denies time and space and hands the initiative to the adversary.

Consider the following scenario: In broad daylight, in international waters over the Sea of Japan, North Korean fighter aircraft shoot down a US signals intelligence (SIGINT) aircraft. The aircraft had launched from Atsugi Naval Air Station in Japan and was scheduled to land at Osan Air Base near Seoul. The routine collection mission had occurred hundreds of times in the past, and involved long, predictable transits and orbits off the coast of the DPRK.

Thirty-one US servicemen are killed in the attack. North Korea claims the aircraft penetrated sovereign airspace and was shot down in self-defence. The Pentagon is unable to determine the circumstances of the shoot-down, and the US Administration struggles to mount a credible response. A carrier strike group sails to the area as a show of force but, lacking detailed information on North Korean intent, the US is unwilling to take further action. The Secretary of State later says the US response during the crisis was “weak, indecisive and disorganised”.

The US investigation, aided substantially by National Security Agency (NSA) insight into activities in the electromagnetic spectrum, concludes the attack was a deliberate and premeditated act of aggression by North Korea. It highlights systemic failings in the command and management of US SIGINT collection capabilities. An after-action review points out the risk of operating intelligence mission aircraft close to threat systems without adequate or ongoing force packaging.

Fast-forward, rewind

This scenario actually happened on 15 April 1969. The aircraft was a Lockheed EC-121M SIGINT platform, callsign ‘Deep Sea 129’, operated by US Navy VQ-1 Squadron, and the mission was considered low risk. Even though the EC-121M shootdown happened more than 50 years ago, the scenario could easily describe contemporary activity in the Sea of Japan or the South China Sea.

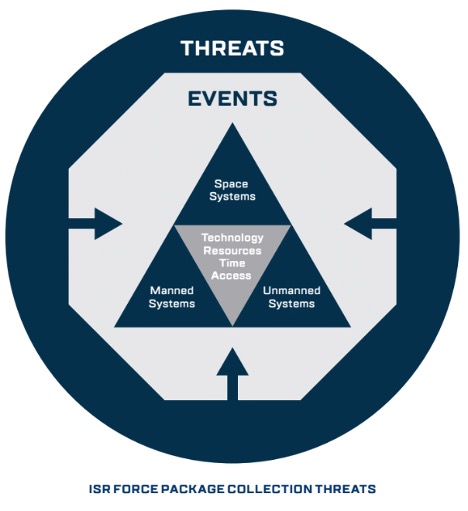

This feature examines the decade in the lead-up to the shootdown of Deep Sea 129 and the development of the force application model which involved the team of manned, unmanned, and space-based systems which characterised the US intelligence gathering apparatus. It highlights the ongoing role of technology, resources, and the time imperative when seeking access to an operational domain.

In conclusion, it considers the impact of operational failure and identifies the weakest link in what we today call Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) and multi-domain command and control.

Shot down…31 US Servicemen died when North Korean fighters attacked a Lockheed EC-121M SIGINT platform over the Sea of Japan in April 1969.

Cold war dark clouds

The USAF and the CIA are both a product of the same National Security Act authorised by President Truman. Signed on 26 July 1947, the Act established the foreign policy framework to fight the Cold War and sets out the priorities for winning.

For the intelligence community, the policy framework quickly yielded results. By the early 1950s Clarence ‘Kelly’ Johnson had advanced the design of the U-2 reconnaissance aircraft at Lockheed’s ‘Skunkworks’. With a similar sense of urgency the USAF Logistics Command established a covert rapid aircraft modification program office called ‘Big Safari’ at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio.

Johnson had previously designed the P-38 Lightning, C-49/C-121 Constellation, F-104 Starfighter, and many other successful designs. But the USAF rejected the unusual U-2 in favour of in-house integration of proven platforms at Big Safari such as the numerous EC-130 and RC-135 variants. Eisenhower, however, directed the CIA to progress with Johnson’s blueprint, and the U-2 flew its first sortie in August 1955 from Groom Lake in the Nevada Desert.

A year later a CIA-operated U-2 overflew the Soviet Union for the first time to conduct photographic reconnaissance of Red Army missile sites. But the U-2 overflights were to be short-lived: in 1957 the Soviet S-75 Dvina (NATO codename SA- 2 Guideline) surface-to-air missile (SAM) system became operational.

After four years of covert operations, the USAF was becoming increasingly concerned about the operational risk associated with the CIA’s U-2 overflights of the Soviet Union, in particular, the fate of the U-2 pilots if they were to be shot down and captured. CIA U-2 pilots were civilians, but they were all drawn from the USAF ranks, having resigned from active duty with a guarantee of a return to the USAF without loss of seniority or rank.

As concerns mounted about the SA-2, the Big Safari office engaged Ryan Aeronautical to examine alternative unmanned options for the mission. Ryan (which was acquired by Teledyne in 1969 and, 30 years later by Northrop Grumman) proposed the conversion of a Q-2C Firebee target into a strategic reconnaissance drone, and a proposal was delivered to the Air Force in April 1960.

On May Day, two weeks later, a CIA U-2 was launched from Peshawar in Pakistan to overfly Soviet missile and nuclear facilities, and land at Bodo in Norway. The U-2 was shot down by an SA-2 battery and the pilot, Gary Powers, was captured by the Soviets and would spend the next three years in prison.

The political fallout from this event was significant and prolonged. Eisenhower was forced to trade-off operational capability for political capital, and the Cold War took a turn for the worse. He immediately cancelled manned U-2 overflights of the Soviet Union and accelerated the work on satellites, while the USAF accelerated work on drones.

Operational complacency – and by extension, command – was identified as a major factor in the shootdown. The political fall-out spread to other theatres which limited CIA U-2 access and, given the immaturity of satellite technology at the time, provided a window of opportunity for the UAV.

Red Wagon

Following the Gary Powers shootdown a tender was issued for a new unmanned reconnaissance system dubbed Red Wagon. The USAF were strong advocates for the UAV as was the CIA, but Red Wagon faced stiff competition from the growing power of the US space community who had by now successfully launched the Corona reconnaissance satellite, Discoverer 14 in August 1960.

Red Wagon also had to compete with another classified CIA program called Oxcart, which was a very high speed manned high-altitude reconnaissance which resulted in the Lockheed A-12, codename Archangel. The A-12 was designed to use height and speed to access the interior of the Soviet Union and China and survive the increasingly lethal SAM threat and, once again Kelly Johnson was the chief engineer. The Mach 3.5 CIA A-12 could fly at 90,000 feet, and would later evolve into the USAF’s SR-71A Blackbird.

The Red Wagon UAV project was therefore cancelled, and the USAF continued modification of its manned aircraft at Big Safari. But of greater significance was the formation of the secretive National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) in 1960 to synchronise and integrate the policy, process and technology aspects of the USAF, CIA, and later US Navy’s strategic ISR platforms. And the NRO had very deep pockets.

In 1962, the NRO funded the ongoing development of the highly-classified USAF prototype Q-2C Firebee drone, which was dubbed the Model 147A FireFly. The Model 147A carried a wet film camera from the U-2, and was designed without landing gear, was launched from the wing of a modified C-130 Hercules drone control aircraft, and was recovered awkwardly by parachute.

Later the same year, US intelligence was alerted to the build-up of Soviet SA-2 SAMs and medium and intermediate range nuclear missiles in Cuba. At this point the Corona satellite capability was still no match for the U-2, so CIA U-2 reconnaissance missions – flown by USAF pilots this time rather than civilians – confirmed the missile locations on 14 October 1962.

Two weeks later a U-2 flown by Maj Rudolph Anderson was shot down by an SA-2. Maj Anderson was killed in the incident which once again triggered renewed interest in the unmanned FireFly, so it was prepared for immediate deployment. But then USAF Chief of Staff, Gen Curtis LeMay chose to hold it back due to the immaturity of this secretive ‘black’ program: he only had two prototypes and wanted to protect their existence from the Soviets.

So U-2 sorties over Cuba re-commenced, and the FireFly missed its chance for an operational debut. But this period would mark the beginning of an extraordinary level of UAV development for the USAF funded substantially by the NRO.

As the threat and operational risks continued to escalate, the FireFly would experience a decade of successful combat employment alongside manned platforms in South-East Asia and beyond.

Lightning Bug

The FireFly code name was compromised in 1963, so it was re-named as the Lightning Bug. At this stage, it was still operated in strict secrecy.

Once again, it would be an international incident which would trigger the shift in the operational risk profile, and it was the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964 which provided the impetus to deploy the Lightning Bug to Kadena AB in Japan. From there it overflew predominantly Chinese targets, but in 1965 its mission was expanded to Vietnam following the high-profile shootdown of a USAF F-4C Phantom east of Hanoi by an SA-2 in the early stages of Operation Rolling Thunder.

This time, the Lightning Bug would prove its utility as an expendable platform used to detect and transfer, by real-time datalink, the sequence of acquisition, tracking, guidance, and warhead fusing signals associated with the SA-2 and its radar, code named FANSONG.

Teamed with manned DC-130, RB-47, or EC-121 platforms stationed over the 7th Fleet in the South China Sea, the Lightning Bug allowed the US to develop countermeasures and tactics which likely saved the lives of dozens of aircrew throughout Operations Rolling Thunder and Linebacker I and II.

As in all cases, though the threat adapted and North Vietnam’s air defences improved, especially through the acquisition of the MIG-21 from the Soviet Union. By 1966 the air-to-air threat forced the U-2s and other manned ISR platforms to fly further away from Hanoi and other key targets which resulted in the Lightning Bugs taking on a broader spectrum of roles and higher risk missions. The expansion in roles included high and low-altitude photographic and electronic reconnaissance, surveillance, airborne decoy, electronic warfare, SIGINT, battle damage assessment (BDA), chaff laying, and psychological operations.

Air combat activity in North Vietnam peaked in 1967 and, in early 1968, events on the ground diverted the USAF and USN air operations away from Rolling Thunder in the north to support the siege at Khe Sanh in the south. The Tet Offensive at the end of January further diverted attention, and President Johnson finally ordered a halt to the bombing campaign in April 1968. But air operations in the broader region continued, with aircraft such as the EC-121, operated by both USAF and US Navy by now, continuing the ISR missions as part of the 7th Air Force and 7th Fleet respectively.

When access allowed, manned ISR platforms such as these and the A-12, and later, the SR-71A remained the most effective and efficient way of conducting ISR missions although satellite technology, and the associated datalinks were improving rapidly under NRO direction. Unmanned systems had their utility for special missions, but still had relatively basic navigation systems and rudimentary methods for landing and take-off, and were becoming increasingly expensive to operate.

For the time being, at least while wartime NRO budgets held up, there was a place for space-based, manned, and unmanned capabilities.

Mission fail

Intelligence collection missions continued to have convoluted command and control arrangements with overall accountability shrouded in organisational complexity. For example, EC-121 SIGINT missions could be controlled by the NSA, the USAF, or US Navy, depending upon the nature of the collection.

The EC-121 shot down in 1969 was operating under an established NSA mission called ‘Beggar Shadow’, but it was actually tasked to conduct a US Navy mission in support of 7th Fleet. The profile had been flown hundreds of times before without incident, so the aircraft also contained a training crew and others planning on using the low-risk mission to take liberty in South Korea.

This time the shootdown was not caused by an SA-2 but a pair of MiG-21s. As was the case with Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson before, it was now President Nixon’s turn to deal with the political fallout and the denial of decision-making time and space.

The EC-121 was subsequently withdrawn from the mission and was replaced by the higher-performance, loosely teamed combination of manned EA-3B Skywarriors, the Lightning Bug Model 147TE (modified for the SIGINT role carrying an NSA payload with a real time datalink and a more powerful engine), and the U-2.

The shootdown also prompted the US Navy to develop a faster and more capable platform than the slow piston-engined EC-121. This new aircraft entered service in the 1970s as the Lockheed EP-3E Aries, a modified P-3 Orion. Apart from a more modern airframe, the most significant changes were the result of a specific recommendation calling for the integration of SIGINT with operational information at command and control centres, where real-time decisions could be made based on all-source inputs.

This saw the establishment of the National SIGINT Operations Centre (NSOC), which endures today as the National Security Operations Centre with its responsibilities expanded after the 11 September 2001 attacks.

By the mid-1970s satellite technology had improved to the point where it could perform digital image processing and sophisticated SIGINT missions. The NRO therefore divested itself of the U-2, SR-71A, and Lightning Bug drones and, with them, the generous budget, which by now was under intense pressure due to the cost-cutting following the Vietnam War.

As the money dried up, the USAF could no longer justify the expense of operationally-limited unmanned systems, so humans were put back into higher-risk missions supported by increased investment in electronic warfare and stealth. Despite a few limited appearances in the interim period, including the Gulf War, drone advocates would have to wait until 1994 before the next significant unmanned ISR deployment, that of a Predator to Bosnia.

Rewind, fast-forward

In August last year the USAF released the Next Generation ISR Dominance Flight Plan. USAF Deputy Chief of Staff for ISR, LtGen VeraLinn ‘Dash’ Jamieson, says of the Flight Plan, “the future will consist of a multi-domain, multi-intelligence, government/commercial-partnered collaborative sensing grid.”

While the Flight Plan references machine intelligence and automation in the processing of intelligence, the cross-domain collection capability is still a mix of high altitude, multi-role, and space-based platforms. The idea of teaming manned, unmanned, and space ISR assets might be over 50 years old, but many of the value-for-money trade-off decisions remain substantially the same.

But the difference now is the maturity, and the reduced cost of technology and information management. It is no longer a choice between manned or unmanned, unmanned or space-based systems. Technology enables them to be considered as a complementary team and a system-of-systems to mitigate human limitations and meet the ever-increasing demand for decision-making advantage.

Technology enhances force application, situational understanding, force projection, and force protection functionality by allowing smarter force packaging and more flexible ways of managing operational risk. But technology alone is not the answer. There is an enduring need to adapt and synchronise the policy, legal, process, organisational, and operational elements of a multi-domain ISR effort. Unified command and control is essential to manage operational risk.

The most important factor is integration, without which the weakest link in ISR force application is exposed, forcing us to re-calibrate our operational risk and give up time and space to an adversary.

History tells us the weakest link is the command human factor. Complacency and lack of domain expertise compound errors that go unnoticed for years, the phenomenon of ‘Risky Shift’ causes groups to unknowingly tolerate a greater risk than they would have accepted as individuals, cognitive bias introduces systemic errors in our thinking, and there are many more. This weak leak provides a vector from where we can be deceived, denied, disrupted, or destroyed – the principle effects of the counter command mission.

On the other hand, failure has been central to the development of air and space power; failure which changes priorities, forces the recalibration of operational risk, and a strategic shift in investment. Like the previous U-2 shootdowns, the EC-121M incident did not result in significant retaliation from the US or a declaration of war, but it did drive the development of the more effective, survivable, time-sensitive ISR systems that we see today. It has provided us with the architecture and apparatus of our own sophisticated counter command capability.

The biggest changes in the way we conduct future ISR operations will be determined not by technology, but by humans and events. Events which start as routine ISR missions in the grey zone, but become international incidents and potential triggers for wider conflict. When the next ISR mission incident occurs in the South China Sea it will be a result of the weak link introduced by human factors. It will force us to change our calculation of risk and ask why we became complacent.

This story is not a new one.

This article was published by ADBR on July 23, 2o2o.

The author of the article is John Conway.