Looking Back at Australia’s Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 has been re-lived through every medium, from the humble written word to dramatic full-screen cinematic colour. The day that President Franklin D Roosevelt said would “live in infamy” would inspire the cry to “Remember Pearl Harbor” to be emblazoned upon posters, and motivate a nation in the dark hours of World War 2.

And yet, a surprise attack upon Australian shores just 10 weeks later has largely slipped through the selective cracks of history. The bombing of Darwin on 19 February 1942 by Japanese forces brought the war to Australia’s front doorstep, transforming an emerging threat into a war zone.

ORDER OF BATTLE IMBALANCE

The speed with which the Japanese advanced across Southeast Asia in the final month of 1941 and early 1942 was a whirlwind.

Forty minutes before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese troops were landing on the distant coastline of Malaya where the sun had yet to rise and, in just 70 days, they would advance to defeat British forces in Malaya and force their surrender in Singapore on 15 February. In that timeframe, the Philippines, Burma, Rabaul, and Hong Kong had become a part of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (GEACPS) as the Empire of Japan had dubbed their conquest.

The Japanese had also attacked the island of Timor at midnight on 19/20 December 1941 with the ultimate goal of invading both Timor and Java which were part of the then Dutch East Indies. It was this strategic aim that drew Darwin into the frame, as its location offered an ideal base from which the allies could oppose such an invasion.

In early 1942 an invasion of northern Australia had been proposed by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), but had been rejected because occupying the vast Australian continent was beyond the capabilities of Japanese forces. But the allied forces were unaware of this. Orders relating to an “anticipated landing by Japanese forces” had been issued, with 2,000 women and children evacuated south from Darwin in preparation.

Rather than invade Australia, the Japanese planned to attack the port of Darwin and its infrastructure, as well as the ships at anchor. Military bases, the civil aerodrome, the RAAF airfield, and oil facilities were also targets in the quest to neutralise the ability of Darwin to interfere with Japanese plans to invade Timor and Java.

OPPOSING FORCES

There was a gaping chasm between the readiness of the opposing forces. The defences of Darwin consisted of a small anti-aircraft battery of fewer than 20 guns to deal with high altitude bombers, while low-level aircraft would only be challenged by a series of small calibre Lewis machine guns. A radar installation was not yet operational, leaving the port city without an early warning system.

The RAAF was equipped with a small number of serviceable CAC Wirraways of 12 Squadron, while the few Lockheed Hudsons of 13 Squadron were those that had made it back to Darwin following the downfall of Ambon. Ten P-40 Warhawks of the USAAF 33rd Pursuit Squadron were in transit at Darwin bound for Java.

By comparison, the Japanese forces were plentiful, highly organised, and battle-hardened under the command of Vice-Admiral Chichi Nagumo who had overseen the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Imperial Japanese Navy possessed a task force that included four aircraft carriers, two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, seven destroyers and three submarines. Like their commander, the aircraft carriers, IJN Ships Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū had all seen action at Pearl Harbor, and 80 per cent of the pilots that would take part in the bombing of Darwin were also veterans of that action.

When the time came to attack, the Japanese would launch nearly 200 carrier-based aircraft, comprised of Kate torpedo-bombers, Val dive-bombers, with Zero fighters in escort. The air armada would be further supported by land-based bombers – 27 Betty medium bombers from Ambon, and 27 Nell medium bombers from Kendari in the Celebes.

WARNING SIGNS

Before the bombing, enemy activity had already been evident.

Japanese submarines had been engaged in laying mines in the region during January and had fired upon the oiler USS Trinity, which was being escorted by two other vessels. On their return to Darwin, three Royal Australian Navy corvettes were dispatched with one Japanese submarine ultimately sunk 60km west of Darwin by depth charges. Ten days before the bombing a Japanese Mitsubishi C5M reconnaissance aircraft overflew the city unscathed and reported back on the ships in the harbour and the aircraft parked at the civilian and RAAF airfields.

The Port of Darwin’s waters were busy with vessels from Britain, the US, and Australia fulfilling roles ranging from transports, hospital ships, minesweepers, patrol boats, troopships, and tankers. One destroyer, the USS Peary was undertaking escort duties for convoys to the beleaguered Timor. In company with the USS Houston, the Peary set out for Timor on 18 February, but spotted a Japanese submarine on sonar. The Houston continued but, having burnt valuable fuel over the ensuing chase, the Peary returned to Darwin to top up its tanks and remain overnight in what was to prove a fateful decision.

The next morning, 350 km northwest of Darwin, a lone Japanese reconnaissance aircraft launched from the fleet to report that the weather over Darwin was suitable for the attack. In response to the positive weather report, the aircraft carriers launched 81 Kates, 71 Vals, and 36 Zeros into the sky, for total a force of 188 aircraft.

As the swarm passed overhead Bathurst Island 100km to the north of Darwin, Father McGrath at the Sacred Heart Mission who was also a Coastwatcher relayed a warning that a large number of aircraft had been observed passing overhead at a great height and proceeding southward. The message was received by the officer-in-charge of the Amalgamated Wireless Postal Radio Station at Darwin at 0935, and relayed to the military authorities.

In a chilling echo of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the inbound aircraft was considered to be returning friendly aircraft, and no alert was raised in Darwin. As the Japanese fighters and bombers approached Darwin, the 10 USAAF P-40s were also inbound, having turned back on their planned flight to Timor due to inclement weather. As five of the Warhawks entered the traffic pattern, the other five remained overhead. Soon they were engaged by a lone Zero which had earlier left the main formation and within minutes, the Zero had downed four of the Warhawks.

At 0958 the main Japanese force arrived overhead and, only then did the air raid alarm sound its warning.

THE BOMBING OF DARWIN

As with Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had achieved total surprise.

Two of the remaining Warhawks were able to become airborne while the others were strafed on the ground, but both were subsequently shot down. This left the anti-aircraft guns as the only remaining defence, but they were soon under attack from strafing Zeros.

Unlike Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Kates directed their attack not at the ships but at the wharves, hospital, offices, and police barracks, leaving Darwin ablaze. Next, the Vals divided their attacks between the port and the airfields.

The 55 ships in Darwin Harbour then became the focus of the fighters and bombers, with the MV Neptuna at the dock particularly vulnerable unloading its shipment of depth charges. Three PBY Catalina flying boats were destroyed on the water, while the USS Peary was hit by five bombs. She broke apart and a few hours later would sink to the bottom with the loss of 91 lives.

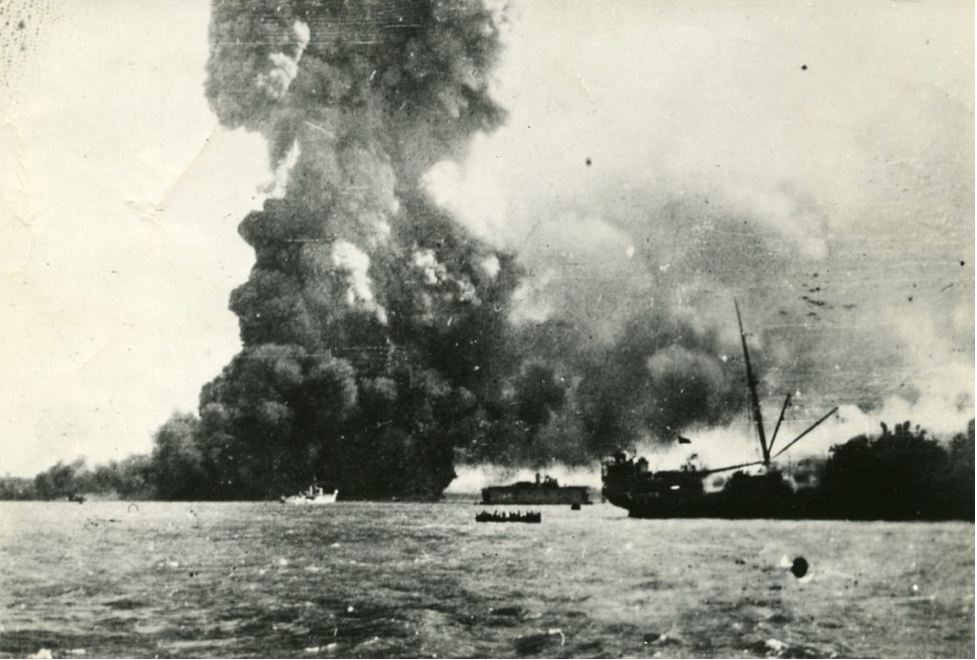

The hospital ship HMAHS Manunda made its way towards the Peary’s survivors, and had 12 of its crew and many more wounded aboard as it too came under fire. Other vessels were sinking or being beached when the harbour was rocked by an explosion of mammoth proportions. The MV Neptuna had been struck, detonating its cargo of depth charges and killing 45 people on the ship and adjacent wharf, with many more injured.

After 30 minutes the attacking fighters and bombers re-grouped and departed, led by their commander, Commander Mitsuo Fuchida who had been the Air Group Commander at Pearl Harbor, leading the first wave and ordering that fateful message, “Tora. Tora. Tora.” to be transmitted.

Darwin was now a smouldering port with ships sinking and ablaze, and much of its town centre left in ruins. But there was to be no immediate reprieve. A second wave consisting of the 54 land-based bombers arrived overhead at noon, and the air raid alert sounded again.

The Bettys and Nells headed for the RAAF airfield to destroy whatever the first wave had missed. The bombardment destroyed the runways, the Lockheed Hudsons, and numerous buildings including hangars and the hospital in a series of high-level bombing runs. The second attack was even shorter than the first wave and, after only 20 minutes, the bombers departed.

Later that day two transport ships near Bathurst Island were subjected to attack from the air, having been spotted earlier by the main force as it headed south to Darwin. One was sunk and the other beached itself to avoid the same fate.

As Darwin sought to recover, the losses of the day were heavy. More than 240 civilians and Australian and US service personnel had been killed, and around 320 more were injured. Eight ships were sunk in Darwin Harbour, with the loss of the Peary and the Neptuna accounting for the greatest loss of life.

In addition to the damage to the hospital and destruction of hangars and repair shop at the RAAF airfield, the losses of aircraft were six Hudsons destroyed on the ground, with another badly damaged in a hangar, along with a Wirraway. The Americans lost all 10 P-40s and a B-24 Liberator that was parked on the airfield.

On the civil aerodrome, one 250lb bomb fell in front of the Guinea Airways hangar which was wrecked, and three huts were also severely damaged. Additionally, an ammunition dump containing approximately 300,000 rounds of .303 ammunition was destroyed.

By comparison, the Japanese losses were negligible, comprising just four aircraft. One of those was a Zero piloted by Petty Officer Hajime Toyoshima which crashed on Melville Island. Toyoshima was captured by a local Tiwi man, Matthias Ulungura, and was the first prisoner of war taken on Australian soil. Toyoshima died in the early hours of 5 August 1944 shortly after he had used a bugle to signal the commencement of the Cowra Breakout which saw 231 Japanese prisoners killed or commit suicide.

The bombing of Darwin had been an overwhelming victory for the Japanese. They had once again achieved the element of surprise and, in bombing Darwin, expanded their operation to include targets beyond those at rest on the water.

Even so, The commander of the IJN First Air Fleet, Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo would famously be quoted as saying that the attack on Darwin was akin to, “…using a sledgehammer to break an egg”.

THE AFTERMATH

For many in Australia, the bombing of Darwin was seen as a prelude to an invasion and, contrary to some reports, the news of the bombing was not hidden from the public.

The national newspapers published the next day reported the raid, albeit scaling down the damage and casualties. Prime Minister John Curtin, was quoted as saying that, “…damage to property had been considerable”, and, “Though information did not disclose details of casualties, it must be obvious that we have suffered”.

Darwin was not to be a lone strike against Australian soil from the air, but the scale and level of damage of that first raid was never to be repeated. Following the attack, until November 1943 a further 64 bombing raids were launched on Darwin.

Even more attacks were directed to Australia’s northern and north-western region, with a notable raid on Broome on 3 March 1942 in which 88 people were killed and 22 aircraft destroyed, including eight Catalinas operated by the Royal Australian Air Force, the Royal Netherlands Navy Air Service (MLD), US Navy, and the RAF, two Short Empires belonging to the RAAF and QANTAS, and five MLD Dornier Do 24s. Even today, at low tide some remains of these aircraft can be found and visited on foot.

As the war changed direction, so too did the Japanese focus. The four aircraft carriers that had attacked both Pearl Harbor and Darwin would be sunk at the Battle of Midway and bring Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s run of success to an abrupt halt.

In Darwin, a substantial air defence network was established within months, with coordinated fighters, radar and searchlights, while RAAF, USAAF, and Netherlands East Indies (NEI) bomber squadrons were deployed to deliver strikes against the Japanese from airfields in Australia’s north.

It is now 80 years since the Japanese raid on Darwin, yet the attack is not forgotten. The ranks of the veterans have all but faded but memorials, museums, and educational programs still recount the sacrifices of 19 February 1942.

Poignantly, a recovered 4-inch gun from the deck of the USS Peary sits on the Darwin waterfront. Long silent, it points out to sea towards the sunken destroyer, still on watch eight decades after the bombing of Darwin.

EDITOR’S COMMENT

Saturday 19 February 2022 marks the 80th anniversary of the Japanese Imperial Army’s bombing of Darwin in World War 2. Despite nearly a decade of simmering trade and territorial disputes and tensions in the western Pacific in the 1930s, to say Australia was unprepared for such a brazen attack would be an understatement.

Now, 80 years later, the wider Indo-Pacific is again in an increasingly-tense state. In the past decade, the region has seen some historically dubious territorial claims made, poorer nations in our region saddled with unmanageable levels of debt, flagrant abuses of human rights, and petty trade disputes contrary to the norms established by the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

While the chances of regional conflict currently remain comparatively low when held up against the global chaos in 1941, the lead times required to integrate new capabilities and to grow a force capable of defending Australia’s northern approaches is now measured in years or decades, not weeks or months as it was back then.

The lessons of 1942 show that, of critical importance now as it was then, Australia needs to build and maintain domain awareness of our northern maritime and air approaches, and resilient integrated early warning and air maritime defence systems need to be developed and fielded.

This article was published by ADBR on February 16, 2022 and the editor’s comment is from the editor of ADBR.

The article was written by Owen Zupp.

Featured Photo: The MV Neptuna explodes in Darwin Harbour during attack. (PETER SPILLETT COLLECTION VIA NORTHERN TERRITORY LIBRARY)