The Strategic Shift in Australian Defence Requires a Shift in the Approach for Australian Defence Industry

To achieve the kind of resilience and sustainability which Australia requires in dealing with the threat environment, Australia needs to build more focused defence industrial capability. What kind of capability is most needed in the evolving strategic environment?

To understand the nature of the shift required, I talked with Professor Stephen Frühling. Professor Stephan Frühling teaches and researches at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre of The Australian National University and has widely published on Australian defence policy, defence planning and strategy, nuclear weapons, and NATO.

He is one of the authors of recent comprehensive report precisely focusing on the nature of the shift required for Australian industry, commercial and defence, to support Australia in the new strategic environment. That report was published in December 2023 and was entitled, Defence Industry in National Defence: Rethinking the future of Australian defence industry policy.

The executive summary of the report is as follows:

As our geostrategic environment deteriorates, the Australian Government has adopted the concept of National Defence – the defence against potential threats arising from major power competition – as a new approach to defence planning and strategy.

While many reforms will be required to implement the National Defence concept, building Australia’s defence industry capability is one of the most important. The Defence Strategic Review has argued for the need to build enhanced sovereign defence capabilities in key areas.

However, the current paradigm of defence industry policy was established in a very different context to that of today. Risks of major power conflict were low, policy assumed a 10-year warning time, and industry capability was viewed largely in terms of supporting individual ADF programs.

This report examines the role of defence industry in the context of Australia’s National Defence strategy. It argues that a change is required to recognise defence industry not as an input to capability but as national capability in its own right. The possession of a sovereign but internationally linked defence industry is itself an asset during a period where the risk of major conflict is rising.

To inform the national debate in Australia, this report examines defence industry policy in five countries: Sweden, France, the UK, Israel and Canada. These case studies offer pertinent lessons for how defence industry policy can be implemented in different strategic contexts.

The report identifies several factors that shape effective policy: fostering defence-civilian industry embeddedness; utilising a broad range of industry policy tools; ensuring formal and informal coordination between government and business; balancing competition and strategic relationships; and leveraging international markets for scale.

The report then connects these lessons to Australia, considering how our defence industry policy could be reformed to deliver on the needs of a National Defence Strategy. It offers five recommendations for the future of defence industry policy in Australia.

Policy Recommendations

- The Australian defence industry should be considered a capability in its own right: A capability that supports the ADF force-in-being, but whose strategic value lies in those situations where that force is fully committed, needs to be rapidly reconstituted, and may need to expand. Domestic industrial capability should be developed to meet the demands of our defence planning scenarios, with foundation capabilities in place and capacity to scale with operational needs during conflict.

- Defence industry should be embedded within and managed as part of Australia’s broader national industry structure and policy. Defence industry draws on resources such as capital, technology, infrastructure and skills from the civilian economy, and can achieve better scale and efficiencies when connected to their civilian peers. Industrial policy support for defence industry is integrated with, and not simply alongside that, support offered to its civilian counterparts.

- Defence industries should be strategically prioritised, then supported to achieve scale and surge capabilities. Prioritisation will be required to identify where Australia has relevant capabilities, or might be able to efficiently develop them, that can contribute to our own and allies supply chains. These capabilities should also be aligned to existing areas of strength in Australia’s civilian industries and leverage new industrial policy programs. Scale in these prioritised areas should then be achieved by coordination across programs, the development of export markets, and/or the building of international technology partnerships.

- Government should utilise the full range of policy levers at its disposal to shape defence industry outcomes. This including both formal and informal mechanisms for coordination between government and business, to ensure greater understanding, cooperative relationships, and two-way flow of information. Given the size of Australia’s defence effort, the selective use of single supplier (strategic partnering) arrangements will be crucial in some areas to achieve and sustain required industry outcomes.

- Government should establish a Defence Industry Capability Manager. The Capability Manager would be responsible for defining the capability and capacity that government needs to develop, as well as for development of industry to meet the level of preparedness determined by the Government. Whilst close liaison within the Department of Defence and specific Capability Managers would be required, the Industry Capability Manager would have a wider ‘whole of government’ role to bring Defence, wider government and industry together for the achievement of strategic industrial outcomes.

In our discussion, we focused on three main elements of fundamental change.

First, the traditional focus of Australian government’s relationship with defence industry has been on platform acquisition and sustainment. The (often conflicting) aims were minimizing cost and maximizing jobs in Australia – not creating enduring industrial capacity that could scale or be leveraged to emergent needs. And hence the government has had single platform competitions with fairly little regard for the resulting industry structure or working with a core company to craft an ongoing industrial capacity.

Frühling argued that the focus needed to shift to industrial capability and capacity, notably in what one might call the enablers of military capability, the shooters, C2 and sensors, which can be crafted, evolved and shaped by Australian industry with its own resources and in close cooperation with core partners. Much of the technology enabling C2, sensors and even weapons comes from dynamic changes in the commercial sector and Frühling argued that there needed to be a broader focus on the industry ecosystem that could support defence in conflict, rather than on narrowly considered defence industry per se, and certainly a defence industry on a leash from government to compete platforms, choose a platform and manage sustainment of that platform.

I would add that with the shift from platforms to payloads, such a shift is absolutely crucial to shape the kind of focused but integrated force the DSR has hypothesized is necessary. The enablers for the force are increasingly significant and the new class of systems, such as maritime autonomous systems, require a very different relationship between the users and the developers.

In security and combat operations, the use of autonomous systems drives change desired by the users who will demand code changes directly from the code writers.

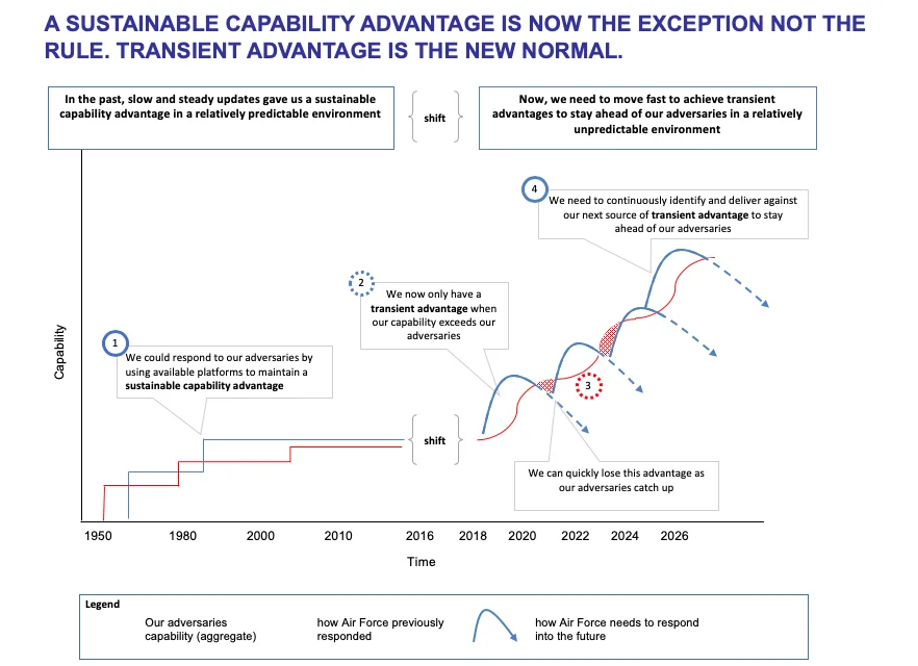

As early as 2015, the RAAF articulated the need for this change and called it the capability for software transient advantage (as seen in the featured image). That need is now center stage and the ADF needs a different working relationship with industry to achieve this crucial warfighting and security capability.

Second, there clearly is a need for scale in providing for enough supplies and warfighting capability in times of crisis. Here Frühling underscored what I have called shaping an allied arsenal of democracy. Frühling underscored that Australia had limited capacity to produce platforms but by focusing on weapons, sensors and C2, it could build depth of supply in a crisis that could leverage platforms of opportunity if required – much akin to the rapid innovation we now see in Ukraine.

Hence, third, there is the importance to master systems engineering for integrating C2, ISR and weapons on a variety of platforms in times of crisis. For example, commercial vessels and novel use of autonomous platforms could be configured with C2, ISR, and weapons capabilities in times of crisis.

Frühling noted the the government strategic investment in CEA radars was an example of moving in the right direction. CEA radar modules are built into a variety of land, sea and air platforms which gives the company the scale and certainty to deliver the kind of sensing capability which the ADF needs (and they build excellent radars for export as well).

In short, the ADF needs a different kind of defence industrial ecosystem to deliver the capabilities envisaged by the DSR. It remains to be seen whether the cultural changes required to create such a defence industrial ecosystem emerge and drive such a shift.