Autonomous Systems for the Ready Force: It is About the Con-ops

Throughout the day of the Sir Richard Williams seminar on 26 September 2024, speakers highlighted the importance of unmanned and autonomous systems enhancing the capabilities of the ready force, rather than seeing them as part of some future force.

But such systems are best understood as providing payloads for the kill web rather than as platforms which are unmanned or uncrewed. By characterizing them this way, one can envisage how the ready force will get their hands on these systems and use them.

And for this to happen the new systems need to shift from being platforms as science projects to payloads which the warriors can integrate into their concepts of operations. That means as well, the enthusiastic science fiction writers about autonomous systems will have to temper their expectations.

I had a chance to talk about this challenge with Vice Admiral (Retired) Tim Barrett after the seminar. As former Chief of Navy he emphasized that when in office such systems be put into the hands of warfighters rather than isolating them as science projects.

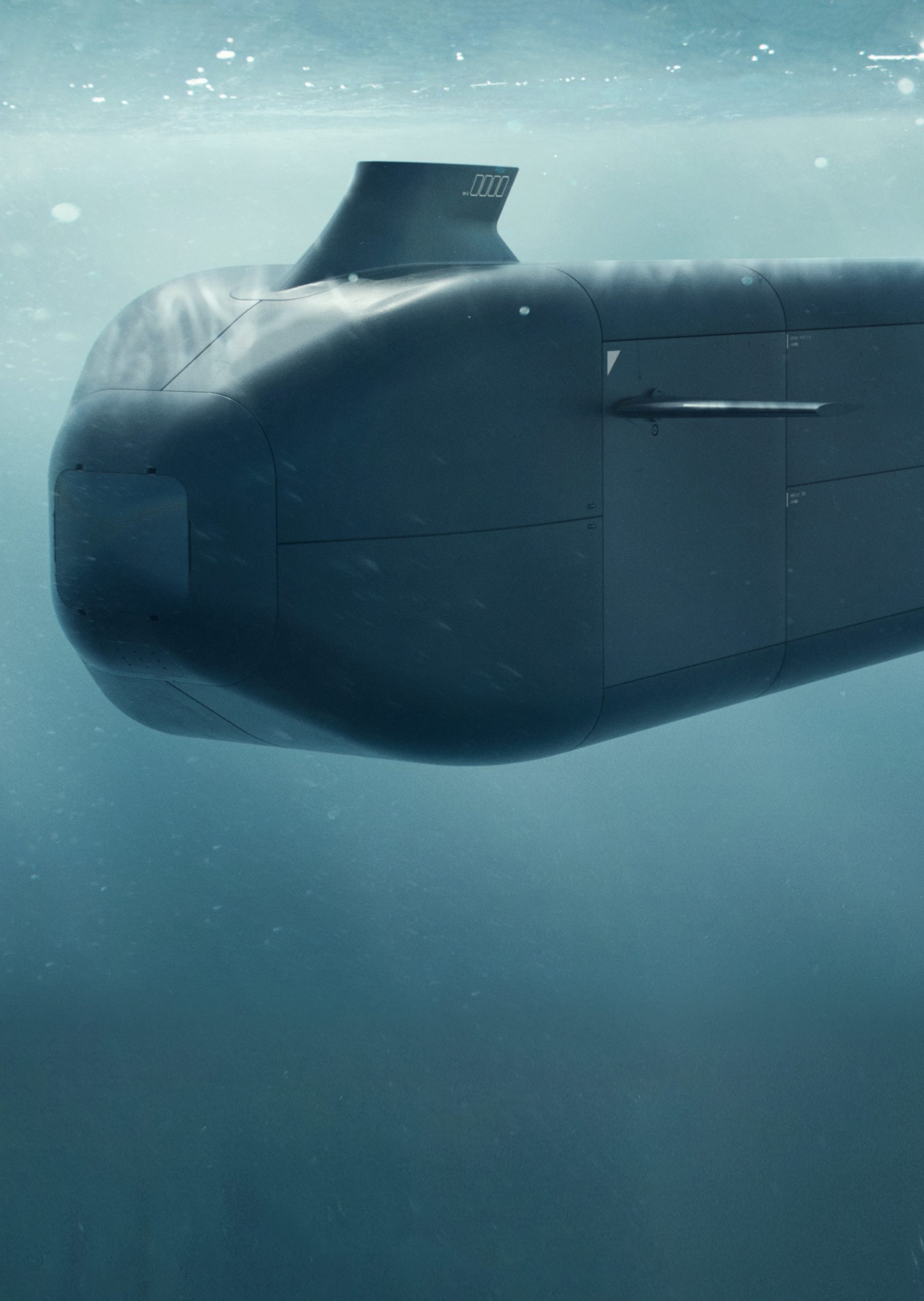

We talked about one such system, namely the Ghost Shark, which is built by Anduril and is being tested and evaluated for use in the near to mid-term.

But as we discussed, for such an ISR capability – for the payloads most useful in the near term by UUVs will clearly be part of the SA network for the Royal Australian Navy and its partners – to be effective it will have to be used by those who manage underwater SA and operations in the RAN.

This is how Barrett put it:

The reality is that for autonomous systems to come into the current force, they need to be well practiced at the operational end – promotion of their adoption is a behavioral piece. New systems need to be in the hands of warfighters to ensure that these systems make the current force more agile and take actions that are effective in their application.

Operational success is still about the application of force in the mind of the person responsible for delivering it. It’s about forcing them to think of operational success by whatever means they have available to them, and then having the courage to take those actions.

You are not necessarily after disruptive change in process, but disruption in the effect. In some cases you don’t want disruption in the efficiency of the process of operations. But, you want to be able to cause a disruption that has an effect on your adversary.

With regard to the Ghost Shark, to fully achieve its potential, it has to quickly enter the operational world of those who are managing the underwater warfare space throughout the regions of our interests.

To be effective as a disruptive technology, it will need to contribute to the operational effects being sought by those managing the undersea domain; in tactical terms this means it has to be of benefit to those managing the water column. It could generate strategic consequences but not simply because of its technology but in the way this it is used to produce disruptive operational effects.

A successful water space management process is key to being able to determine where your adversary is, or, more importantly, where it isn’t, so that you can put the right forces in the right place.

Bureaucracies don’t necessarily think like that. Operators absolutely do so, because it’s their day-to-day business, and they’re in the practice of only putting in harm’s way those things that need to be there to affect a disruption to the enemy’s operations.

The disruptive effects that a Ghost Shark can produce should be determined by those who actively manage the battle space, the undersea battle space, rather than someone who’s programming from afar and doing so in complete isolation from the rest of the water space management concepts of operations.

Featured graphic: The Ghost Shark, an autonomous robotic undersea warfare vehicle is being designed and manufactured in Australia for the Royal Australian Navy. Credit: Australian Department of Defence.