An Update on the US Navy’s Approach to Maritime Remotes

Recent presentations by senior US Navy officials at the annual conference of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), articles by USNI News triggered by those presentations, and a Congressional Research Service report, provide an update on the US Navy approach to shaping its way ahead with regard to maritime remotes.

In this article, I will provide an overview by drawing upon those sources, and in the next will discuss how best to understand the coming of the maritime remotes.

In effect, the maritime remotes are a platform specific payload carrying asset. And they provide capabilities within an overall evolving kill web redesign of the force.

Ghost fleets have hardly arrived; but clearly, in this decade we will see the arrival of maritime remotes as part of the overall transformation of the fleet.

And given that the current Commandant of the USMC has focused on support for maritime missions, the USMC will be reshaped by how the US Navy designs its maritime remote additive to the combat fleet.

The baseline CRS report published on September 8, 2020, provides an update entitled, “Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles: Background and Issues for Congress.”[1]

The report highlights the current vessels under examination, and puts them into the broader focus on shaping a distributed architecture for fleet operations.

The report also highlights the efforts of the US Navy leadership to proceed from testing to operational engagement within the relatively near term, to get the kind of operational experience necessary to insert maritime remotes within the fleet combat force.

According to the report:

“The Navy in FY2021 and beyond wants to develop and procure three types of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). These large UVs are called Large Unmanned Surface Vehicles (LUSVs), Medium Unmanned Surface Vehicles (MUSVs), and Extra-Large Unmanned Undersea Vehicles (XLUUVs). The Navy is requesting $579.9 million in FY2021 research and development funding for these large UVs and their enabling technologies.

“The Navy wants to acquire these large UVs as part of an effort to shift the Navy to a more distributed fleet architecture.

“Compared to the current fleet architecture, this more distributed architecture is to include proportionately fewer large surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers), proportionately more small surface combatants (i.e., frigates and Littoral Combat Ships), and the addition of significant numbers of large UVs.

“The Navy wants to employ accelerated acquisition strategies for procuring these large , so as to get them into service more quickly. The Navy’s desire to employ these accelerated acquisition strategies can be viewed as an expression of the urgency that the Navy attaches to fielding large UVs for meeting future military challenges from countries such as China.”

Maritime remotes are viewed not as end in of themselves capabilities, but as relatively inexpensive, and in some cases, disposable assets which can deliver payloads into the littoral and blue water battlespace.

The overall objective is to shape a distributed fleet able to operate within more survivability and lethality.

We will discuss this objective and the relationship to the roll out of maritime remotes more fully in the next article.

As the report notes: “The Navy wants to acquire the large UVs covered in this report as part of an effort to shift the Navy to a new fleet architecture that is more widely distributed than the Navy’s current architecture.

“Compared to the current fleet architecture, this more distributed architecture is to include proportionately fewer large surface combatants (or LSCs, meaning cruisers and destroyers), proportionately more small surface combatants (or SSCs, meaning frigates and Littoral Combat Ships), and the addition of significant numbers of large UVs.”

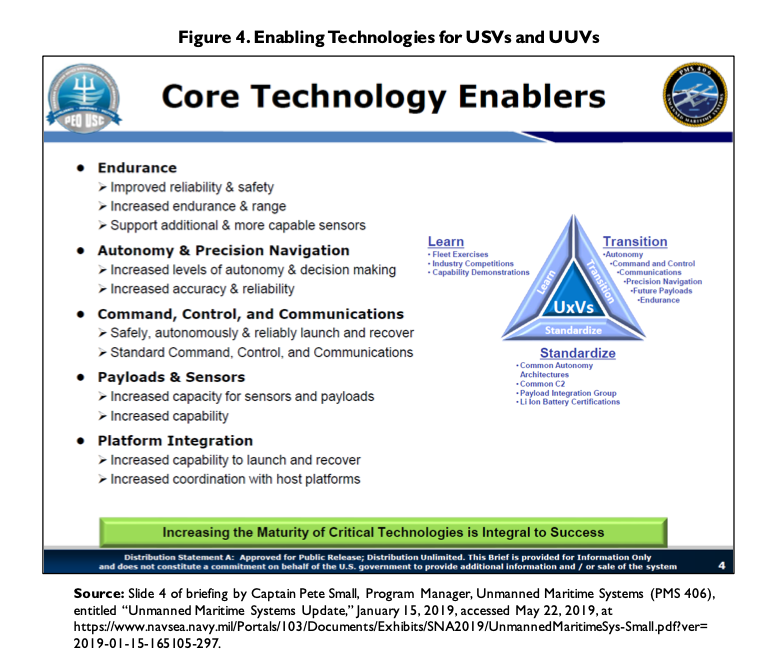

With regard to the remotes themselves, the report includes a slide (seen above) which was included in a briefing by Captain Pete Small in 2019 which highlighted what he referred to as the core technology enablers.

What this slide highlights is several different vectors to assess the performance of the remotes themselves.

But to also highlights the background point that they are payloads within a kill web., and the C2/ISR integratability backbone is the foundation from which these remotes contribute to or denigrate the force within which they operate.

The report provides a useful foundation from which to discuss maritime remotes and their way ahead.

Let me now turn to the perspectives of senior US Navy officers highlighted in recent USNI News articles.

Notably, one of these articles highlights what is often overlooked – although maritime remotes are cool, their value depends upon the frameworks within which they can operate and, to do so, without disrupting combat networks but rather enhancing them.

To achieve this, the overall challenge is to shape software common standards.

When I worked on the Offshore Patrol Vessel report in Australia earlier this year, a key point was that the Australian Department of Defence had made a key decision to work platform build and mission system evolution as two separate but integratable efforts. The Aussies want the mission systems to be integrable across their naval force, and to not have platform orphans. And they want to do such integration, not as after-market integration but part of an overall approach to build out an integrated distribute force.

The US Navy is much larger of course, and has been built with very different classes of ships with little integratabilty in the mission systems built in.

With regard to the coming of maritime remotes, the US Navy wishes to go down the Aussie path, and not the US Navy legacy path.

In a September 19, 2020 article by Megan Eckstein, Navy officials highlighted the importance of shaping common software standards as the backbone of building out maritime remotes and ensuring they add capability, rather than degrade it.

Vice Adm. Jim Kilby, the Navy’s deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities (OPNAV N9), said future unmanned systems are likely to have government-furnished vehicle control systems, data management systems, autonomy packages and more.

“Perhaps a program could be unburdened from having to do the requirement of development for a specific network or interface because we’re going to require them to use what we have on another platform. That’s the efficiency” the Navy hopes to achieve as unmanned platforms of all sizes and in all domains proliferate throughout the fleet, Kilby said while talking to reporters today.

Navy acquisition chief James Geurts said during the same phone call that “I also admire the Navy’s ability to separate platform from combat system and C4I system the way we build ships today. You can envision a similar mindset: again, one of the things we’re looking at in this campaign plan is, separate the platform, whether it’s a [large unmanned surface vehicle] or a or a I don’t know what kind of USV – we don’t want to have to reinvent all of the systems every time we have a new platform. And so I don’t want to have to reinvent autonomy algorithms for every individual platform.”

Vice Adm. Jim Kilby, the deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities (OPNAV N9), provided a presentation at the AUVSI conference which underscored the crucial importance of the digital backbone as well for the fleet, within which maritime remotes would need to operate.

“Those enabling technologies are the naval tactical grid.

“So the ability to network and control, C2, all those unmanned vehicles is significant and important.

“Think about the aggregation of that demand on the network and understanding that and making sure we field a network that’s robust enough to handle all our vehicles in many different types of environments,” Kilby said.

“So that is of primary importance to us and has clearly our focus. It’s not just an N2/N6 thing and it’s not just an N9 thing. It’s the platform, sensors, weapons together with the resource sponsor for the networks that will bring this together.”

Kilby referenced the Common Control System, which the service developed for shared command and control across unmanned platforms, as one way the Navy is working to bring integration to the unmanned systems it’s pursuing.

“Think about a single system that allows us to control multiple vehicles. And that’s a requirement for the Navy. So if you have a platform that chooses not to or can’t use the common control station, you have to seek a waiver to do that,” Kilby said.

“Why is this important?

“We view the world in the future of distributed maritime operations in a place where an air vehicle might have control of a surface vehicle and have to pass that control to a manned surface vessel or this unmanned operations center of the future,” he continued.

“The ability to have a single control station that allows us to do that seamlessly will help us with training and the advancement and update of our systems in the future.”

Working with maritime remotes systems within the fleet is clearly not just a technology challenge, but a skill set development one as well.

In an article by Megan Eckstein published by USNI News on September 9, 2020, the author highlighted a panel held at AUVSI which discussed this challenge.

Capt. Hank Adams, the commodore of Surface Development Squadron One (SURFDEVRON), is planning an upcoming weeks-long experiment with sailors in an unmanned operations center (UOC) ashore commanding and controlling an Overlord USV that the Navy hasn’t even taken ownership of from the Pentagon, in a bid to get a head start on figuring out what the command and control process looks like and what the supervisory control system must allow sailors to do.

And Cmdr. Rob Patchin, commanding officer of Unmanned Undersea Vehicles Squadron One (UUVRON-1), is pushing the limits of his test vehicles to send the program office a list of vehicle behaviors that his operators need their UUVs to have that the commercial prototypes today don’t have.

The two spoke during a panel at the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) annual defense conference on Tuesday and made clear that they want to have the fleet trained and ready to start using UUVs and USVs when industry is ready to deliver them.

What is highlighted in the article is the core challenge of cultural change and also training to leverage what remotes most usefully bring to the fight.

In terms of cultural challenges of incorporating unmanned, Patchin said submariners may have a harder time than surface warfare sailors.

“Culturally, I think the biggest barrier we’re going to have is the understanding that, in my day job as a submarine officer, I was trained” to operate a platform that promises 99.999999999-percent reliability, he said, which creates a certain mindset among submariners.

“We can’t afford that in a UUV, so we’re going to be operating a system that has a reliability short of a nuclear power plant that goes to sea and goes to war. So understanding and being able to culturally move between those two worlds poses a cultural challenge to us, if you will, that we have a certain expectation of what good is that may be different when we look at a UUV in the medium form factor that’s affordable.”

Confidence-building is a key part of the process of introducing maritime remotes as well.

Rather than creating a ghost fleet, the challenge is to avoid creating a ghastly fleet.

One does not want maritime remotes introduced ineffectively and disrupt rather than enhance maritime warfighting capabilities.

And this is not just about having great briefing charts and cool demo projects, it is about actually introducing maritime remotes into the fleet and getting enhanced capabilities, rather than training distractions.

At AUVSI, Rear Adm. Casey Moton, the program executive officer for unmanned and small combatants, provided an update on the various maritime remote programs.

But for PEO USC, how many is ultimately important, but our focus now in this prototyping and experimentation and development phase is on the how, and working with our requirements sponsors and the fleet on the what.”

Moton said the “how” piece is clear: putting unmanned prototypes in the water, learning from them, wrapping lessons learned into acquisition plans for the next round of prototypes, and then eventually moving into acquisition of program of record UUVs and USVs….

Moton said during his keynote speech that this work on the UUV and USV vehicles is being supplemented by work at the Program Executive Office for Integrated Warfare Systems to adapt Aegis Combat System common source library code and virtualized hardware for the USVs, and work at PEO C4I to help bring unmanned systems into the netted naval force. He also credited industry for rising to the challenge, with 40 companies of all kinds and sizes under contract with the Navy under an indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity contract for USV family of systems related work, and the six LUSV study contract winners – of eight bidders total – representing a range of expertise.

“All of these efforts – the acquisition work with the Navy and industry, the fleet work, the CNO-directed and integrated Navy work – will together over the next two to three years have us positioned to answer the ‘how’ questions and the ‘what’ questions before we buy program-of-record vessels,” Moton said.

At AUVSI, Rear Adm. Casey Moton also chaired a panel of Navy and USMC resource sponsors who are leading the effort for maritime remotes and their future incorporation into the force.

Maj. Gen. Tracy King, the director of expeditionary warfare on the chief of naval operations’ staff (OPNAV N95), said he wants to put a robot in a potential minefield during mine countermeasures operations instead of putting a manned ship at risk. The fact that the unmanned craft won’t need to be survivable will inherently make them cheaper, making it easier to budget for them in numbers.

Rear Adm. William Houston, the director of undersea warfare (OPNAV N97), said unmanned will allow the Navy to get into places that manned submarines can’t go, either because the UUVs can be designed to be less detectable or because the consequences are lesser if a UUV is discovered.

Rear Adm. Paul Schlise said the USVs in his surface warfare directorate (OPNAV N96) portfolio would provide more persistent sensors and supplemental fire support than the Navy could afford to buy with manned ships and aircraft alone.

All agreed that USVs and UUVs would find room in the budget, since ongoing future force planning efforts have reaffirmed that manned/unmanned teaming will be critical in a future fight.

But Houston said “how fast technology matures, how well we’re able to prototype it, and how well we’re able to get the certainty as we’re shifting from a balance of completely manned systems to a more hybrid approach” will determine how fast the unmanned systems will be incorporated into future undersea warfare budget requests. He called for a measured approach as the iterative prototyping process plays out because, while it would be an advantage to move to unmanned systems because they’re cheaper and therefore he could afford to put more assets in the water, he doesn’t have the money in his budget to go all-in on something that ultimately won’t meet the fleet’s needs.

Manned/unmanned teaming will happen under the water, he said, it’s “just a question of how fast and how much we do that” based on Moton’s ongoing prototyping work.

And next year, PACFLEET will host an exercise to address the role of maritime remotes within the future evolution of the combat fleet.

Rear Adm. Robert Gaucher, director of maritime headquarters at U.S. Pacific Fleet, discussed this exercise and the way ahead with regard to maritime remotes at the AUVSI conference as well.

“We’re shooting for early 2021 to be able to run a fleet battle problem that is centered on unmanned. It will be on the sea, above the sea and under the sea.”

“Everyone wants to talk about the extreme case. We are a long way from the extreme case. What we need to do is get things out there and take these baby steps along the way,” Vice Adm. Ron Boxall, director of force structure, resources and assessment (J8) on the Joint Staff, said in the same session. “

We have to be able to give confidence that we are proceeding at a good pace, but not to the point of stupidity… Because a lot of these platforms are smaller, we can demonstrate things on a much smaller scale as we bring in both capacity and capability further on down the cycle.”

Ultimately, the idea is to create an unmanned system that shares the burden of the manned ships in the fleet. “I want to create dilemmas for the adversary and I want to increase lethality,” Gaucher said. “I want to be able to put an unmanned surface ship inside the adversary’s denied areas. If I lose it, I’m losing a much less expensive ship and I’m not losing American lives, but I’m still creating a problem — whether I’m making them shoot it and I’m finding out where they are … or I’m making them waste a weapon on it or I’m getting a couple of shots off before I lose it.”

Gaucher said his goal, for now, is to, “aim small, miss small.”

“There’s a lot of people out there that, you know, unmanned is kind of this neat thing until you have to start authorizing a robot to go do something,” he said. “All of a sudden you have a lot of questions.”

[1] Congressional Research Service, , “Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles: Background and Issues for Congress,” (Updated September 8, 2020), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/R45757.pdf